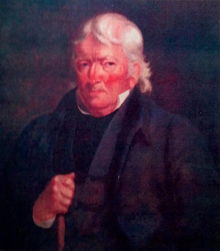

Major John Buchanan (January 12, 1759 – November 7, 1832) was an American frontiersman and one of the founders of present-day Nashville, Tennessee. He is best known for defending his fort, Buchanan's Station, from an attack by a combined force of roughly 300 Chickamauga Cherokee, Muscogee Creek, and Shawnee warriors on September 30, 1792.[1] The defenders of the stockade included fifteen gunmen and his wife, Sally Buchanan, (his second) who was heavily pregnant with their first child.[2]

John Buchanan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 12, 1759 Harrisburg, Province of Pennsylvania, British America |

| Died | November 7, 1832 (aged 73) Buchanan's Station, Tennessee, U.S. (now Nashville) |

| Occupation(s) | American pioneer, settler, frontiersman, farmer |

| Spouses | |

Origins

editJohn Buchanan was the great-grandson of Thomas Buchanan, who left Scotland in 1702 as one of six brothers (John, William, George, Thomas, Samuel, and Alexander) and one sister to resettle in County Donegal, Ireland. John Buchanan and his family, emigrated to America as among the earliest colonists in North America, initially settling in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, where John Buchanan was born in 1759.[3]

Settlement in Cumberland

editTwenty-year-old John Buchanan and his family arrived at the future Nashville during the unusually cold winter of 1779–1780, ahead of James Robertson's founding party according to several historians. After losing his brother Alexander at Ft. Nashborough's 1781 "Battle of the Bluff," Buchanan wrote Nashville's first book, John Buchanan's Book of Arithmetic.[4]

After living approximately four years at Fort Nashborough, Buchanan and his family moved a few miles east and established Buchanan's Station on Mill Creek, at today's Elm Hill Pike and Massman Drive in Nashville. Around 1786, Buchanan married Margaret Kennedy, who died after giving birth to their first and only child, John Buchanan III, born on May 15, 1787. His second wife, Sarah Ridley, bore thirteen children: George, Alexander, Elizabeth, Samuel, William, Jane T., James B., Moses R., Sarah V., Charles B., Richard G., Henry R., and Nancy M.

As G.R. McGee writes in A History of Tennessee from 1663 to 1905, "[i]n the summer of 1780 the Indians began to kill the settlers and hunters that they found alone or in small parties, and this was kept up all the season. There was no open attacks upon the settlements, but if a man went out to gather corn, to hunt, to feed his stock, or to visit a neighbor he was in constant danger of being shot by an Indian hidden away in a thicket or canebrake."[5]

Attack on Buchanan's Station

editOn September 30, 1792, during the height of the Cherokee–American wars, approximately twenty defenders at Buchanan's Station held off several hundred Native Americans seeking to destroy all the Cumberland settlements. Buchanan and his compatriots stopped them—without the loss of a single stationer—before they could move on to attack the remainder of area settlements. Nineteenth-century historian J.G.M. Ramsey called this victory "a feat of bravery which has scarcely been surpassed in all the annals of border warfare."[6]

Buchanan's Station was located on Mill Creek and consisted of a few buildings surrounded by a picket stockade and a blockhouse at the front gate overlooking the creek some four miles south of the infant settlement of Nashville.[7] For most of the 19th century, Buchanan's Station was widely remembered as a symbol of the determination that created the State of Tennessee.[7]

At the time, Nashville consisted of only about sixty families, and it was isolated in a hostile and threatening wilderness. Communications with the nearest settlements, Knoxville in eastern Tennessee and Natchez further south on the Mississippi, were long and precarious. Although the ultimate responsibility for the area had been transferred from North Carolina to the United States federal government in 1790, neither entity had the will or resources to offer the small outpost effective protection. Ranged against it were Native Americans, understandably aggrieved at the loss of traditional territory, and international powers. Threatened by the rise of the new American republic, Britain and Spain both encouraged Indian confederacies to resist its expansion and create a buffer between it and their own colonial possessions. North of the Ohio, the British saw Indians as an essential part of the defense of Canada, while Baron Carondelet, the governor of Spanish territory south of the 31st parallel and west of the Mississippi, armed the southern Indians and urged them to unite against the Americans. It was time, one Spanish correspondent wrote, to "place an obstacle to the rapid western progress of the Americans and raise a barrier between these enterprising people and the Spanish possessions." [citation needed]

The assault on Buchanan's Station was not a simple raid, but an attempt to wipe out the Nashville settlements entirely, backed by Spanish arms and supplies secured in Pensacola.[7] Over three hundred Lower Cherokees, Creeks, and Shawnees under the command of a mixed blood Cherokee leader named John Watts, advanced on Nashville from their towns on the lower Tennessee River.[7] Supposing that the outlying station of Buchanan could be disposed of quickly, the Indians attempted a surprise attack at midnight. The station contained only a handful of defenders, some fifteen men, who manned the port-holes while their women and children—led by Buchanan's wife—molded bullets, reloaded muskets and rifles, and supplied sustenance.[7] During a furious fight, the Indians attempted to storm the palisade and to set fire to the roof of the blockhouse, but they were repelled within two hours.

Sally Ridley Buchanan

editIt was during this nighttime "Battle of Buchanan's Station" that Buchanan's eighteen-year-old wife, Sally Buchanan (née Sarah Ridley), in her ninth month of pregnancy with the first of their thirteen children, earned national fame. She encouraged the men, reassured the women and children, molded much-needed ammunition reportedly by melting down her dinnerware, and provided the voice of victory throughout the seemingly hopeless pandemonium.[7] For her uncommon valor, she was known as the "Heroine of Buchanan Station" and biographer Elizabeth Ellet referred to her as "the Greatest Heroine of the West".[2] Sally was heralded in magazines and newspapers as well as listed in at least two national encyclopedias of biography (Appleton's and Herringshaw's).

Additional Information

editReferences

edit- ^ Aiken, Leona Taylor (1968). Donelson, Tennessee: Its History and Landmarks.

- ^ a b Ellet, Elizabeth (1873). The Eminent and Heroic Women of America. New York: McMenamy, Hess. pp. 721–725.

- ^ Buchanan, Thomas. "Thomas Buchanan's Memoirs – 1898". Retrieved May 27, 2013.

- ^ Buchanan, John (1781). John Buchanan's Book of Arithmetic. site of present-day Nashville, TN: Buchanan, John. p. 82. Tennessee Historical Society miscellaneous collection, I-A-1v, B-238, T-100.

- ^ McGee, Gentry Richard (1911). A History of Tennessee from 1663 to 1914. New York: American Book Company. pp. 88–89.

- ^ Ramsey, J.G.M. (1853). Annals of Tennessee. Charleston, J. Russell.

- ^ a b c d e f Sugden, John (1997). Tecumseh: A Life. Henry Holt and Company. pp. 73–76. ISBN 9780805061215.