Allar (Arabic: علار) or 'Allar el-Fawqa ("Upper Allar"), also known as 'Allar el Busl,[4] was a Palestinian Arab village located southwest of the Old City of Jerusalem near Wadi Surar ("Valley of Pebbles"), along Wadi Tannur. The name was shared by the twin village of Allar al-Sifla ("Lower Allar") or Khirbat al-Tannur, with official imperial ledgers often listing them both under the single entry of Allar.[5]

Allar

علار | |

|---|---|

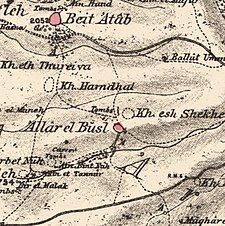

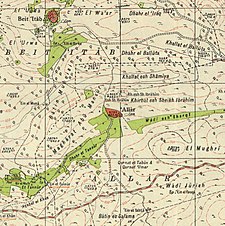

A series of historical maps of the area around Allar, Jerusalem (click the buttons) | |

Location within Mandatory Palestine | |

| Coordinates: 31°43′23″N 35°03′41″E / 31.72306°N 35.06139°E | |

| Palestine grid | 155/125 |

| Geopolitical entity | Mandatory Palestine |

| Subdistrict | Jerusalem |

| Date of depopulation | October 22, 1948[2] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 12,356 dunams (12.356 km2 or 4.771 sq mi) |

| Population (1945) | |

| • Total | 440[1] |

| Cause(s) of depopulation | Military assault by Yishuv forces |

| Current Localities | Mata,[3] Bar Giora[3] |

Habitation in the village spanned centuries and is attested in architectural remains and documents from the Crusader, Mamluk, Ottoman and Mandate Palestine periods. Allar was depopulated during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War and the area was incorporated into the State of Israel, with the moshavs of Mata and Bar Giora established on its former lands.

History

editThe older of the two villages appears to have been Lower Allar. Remains of a Crusader-era church and cloister made up of five other vaulted buildings attest to habitation there in the 12th century. One of these buildings is thought to be a Cistercian house, a sister house of Belmont built in 1161, known as Saluatio.[6]

From the 13th to 16th centuries, the villages were ruled by the Mamluk Sultanate based in Cairo and appear together in a document dating to circa 1264 that lists land grants made in Palestine by the sultan Baybars to his emirs.[5]

Ottoman era

editToward the beginning of four centuries of rule over the area by the Ottoman Empire, in August 1553, two leaders of Allar were held accountable for the village failure to pay taxes and were arrested by the imperial authorities.[7] The imperial tax register of 1596 lists Allar as part of the nahiya ("subdistrict") of Jerusalem with 37 households, an estimated 204 inhabitants, all Muslims. The villagers paid a fixed 33,3% tax−rate on various agricultural products, such as wheat, barley, olive trees, molasses, goats, and beehives; a total of 11,400 akçe. All of the revenue went to a waqf.[8][9]

The waqf custodian of the mosque in Allar (and that of Bayt Nuba) in 1810 was appointed by the Ottoman authorities, and hailed from the Jerusalem family of notables, the Dajanis.[10] Also in the village was a shrine dedicated to al-Shaykh Ibrahim ("Abraham the Sheikh").[9]

Western travellers who wrote of the village include Edward Robinson, who travelled throughout Palestine and Syria in 1838 and Victor Guérin, whose travels spanned many years in the latter half of the 19th century. Both describe Lower and Upper Allar as two distinct villages located in a valley. Robinson calls it er-Rumany wadi ("Pomegranate Valley"), while Guérin calls it Oued el-Limoun ("Valley of the Lemons/Limes"), so named because of the abundant presence of a variety of citrus tree there known to the Arabs as limoun. Both note the presence of a large, ancient, ruined church in Lower Allar. Robinson describes a fine fountain further up the valley that irrigated fruit trees and gardens below, noting the abundance of olive trees. Guérin describes A'llar es-Sifla ou et-Tahta as an oasis covered in grape vines, citrus, pomengranate and fig trees, irrigated by an ancient canal and a second inexhaustible water source.[11][12]

In 1856 the village was named Allar el Foka on Kiepert's map of Palestine published that year,[13] while an Ottoman village list from about 1870 counted 56 houses and a population of 176, though the population count included men only.[14][15]

In 1883, the PEF's Survey of Western Palestine (SWP) described Ellar as "A small village on the slope of a ridge, with a well to the south. On the north are rock-cut tombs.[16]

The inhabitants of Upper Allar moved to Lower Allar at the end of the 19th century.[17]

In 1896 the population of Allar was estimated to be about 243 persons.[18]

British Mandate era

editWhile Upper Allar was repopulated during the period of British rule in Mandatory Palestine and housed a primary school, it is listed in British censuses from the time as a mazra'a ("farm").[17]

In the 1945 statistics, Allar had a population of 440 Muslims,[1] and the total land area was 12,356 dunams.[19] 353 dunums were irrigated or used for orchards, 2,234 dunams were for cereals,[20] while 12 dunams were built-up (urban) Arab land.[21]

-

'Allar, Mandate survey, 1:20,000

-

'Allar, 1945, 1:20,000

1948, aftermath

editDuring the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, Allar was depopulated as a result of a military assault by Israeli forces on 22 October 1948.[2] It was one of a series of villages occupied during Operation Ha-Har, an offensive launched by Harel Brigade and Etzioni Brigade to widen the Jerusalem corridor.[22] Refugees who camped in the nearby gullies and caves were driven out in subsequent raids.[22]

After the Arab-Israeli War of 1948, the ruin of Allar remained under Israeli control under the terms of the 1949 Armistice Agreement between Israel and Jordan.[23][24]

Two Israeli sites were founded on Allar land in 1950: Mata and Bar Giora.[3]

Refugees from Allar and other Palestinian villages who are old enough to remember life there express nostalgia for the natural abundance of the land lost. One Umm Jamal recalls eggplants, pomegranates, cucumbers and green beans as among the many products grown on the village lands which were fed by springs known to locals as Umm al-Hasan ("Mother of Goodness"), Umm al-Sa'd ("Mother of Happiness"), Umm Nuh ("Mother of Noah"), al-'Uyun ("The Eyes"), and Umm al-'Uyun ("Mother of the Eyes").[25]

In 1992 it was described: "Stone rubble, concrete blocks and slabs, and steel bars litter the site, together with the remains of stone terraces and walls. One domed stone structure, the former school building, still stands. On the slopes overlooking the site, almond and cypress trees and cactuses grow along the terraces."[26]

Maqam

editIn 1863 Victor Guérin described a maqam north east of the village, called Khirbet Cheikh Houbin. He noticed it contained ancient fragments used in the building.[27]

In 1883 SWP called it Khurbet Hubin, The ruin of Hubin, from personal name,[28] and gave the description: "Foundations of a small ruined village with a Kubbeh."[29]

References

edit- ^ a b Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 24

- ^ a b Morris, 2004, p. xx, village #346. Also gives cause of depopulation.

- ^ a b c Khalidi, 1992, p. 266

- ^ Based on Palestine Exploration Fund Map of 1880

- ^ a b Petersen, 2001, p. 92

- ^ Pringle, 1993, pp. 47-51

- ^ Singer, 1993, p. 44

- ^ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p.113, cited in Khalidi, 1992, p.266

- ^ a b Khalidi, 1992, pp. 266-267

- ^ Kushner, 1986, p.111

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, p. 340

- ^ Guérin, 1869, pp. 379-380

- ^ Kiepert, 1856, Map of Southern Palestine

- ^ Socin, 1879, p. 143

- ^ Hartmann, 1883, p. 145 also noted 56 houses

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, p. 25, cited in Khalidi, 1992, p. 266

- ^ a b Kark and Oren-Nordheim, 2001, pp. 267, 275-276

- ^ Schick, 1896, p. 122

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 56 Archived 2008-08-05 at the Library of Congress Web Archives

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 101 Archived 2018-06-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 151 Archived 2018-06-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b 'Allar, Palestine Family.net Allar, Palestine Family.net[usurped]

- ^ The 1949 Armistice Agreement between Israel and Jordan

- ^ "Enlarged map showing Allar in relation to the "Green-Line"". Archived from the original on 2017-10-23. Retrieved 2017-05-26.

- ^ Davis, 2011, p. 24

- ^ Khalidi, 1992, p. 267

- ^ Guérin, 1869, p. 383

- ^ Palmer, 1881, p. 305

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, p. 114

Bibliography

edit- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Davis, Rochelle (2011). Palestinian Village Histories: Geographies of the Displaced. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-7313-3.

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945.

- Guérin, V. (1869). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 1: Judee, pt. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center. Archived from the original on 2018-12-08. Retrieved 2009-08-18.

- Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149.

- Hütteroth, W.-D.; Abdulfattah, K. (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Kark, R.; Oren-Nordheim, Michal (2001). Jerusalem and its environs: quarters, neighborhoods, villages, 1800-1948 (Illustrated ed.). Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-2909-2.

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Kushner, David (1986). Palestine in the late Ottoman period: political, social, and economic transformation. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-07792-8.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Palmer, E. H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. (p. 283 )

- Petersen, Andrew (2001). A Gazetteer of Buildings in Muslim Palestine (British Academy Monographs in Archaeology). Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-727011-0.

- Pringle, D. (1993). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: A-K (excluding Acre and Jerusalem). Vol. I. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39036-2.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1856). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 2. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Singer, A. (1994). Palestinian peasants and Ottoman officials: rural administration around sixteenth-century Jerusalem (3rd, Illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47679-9.

- Schick, C. (1896). "Zur Einwohnerzahl des Bezirks Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 19: 120–127.

- Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163.

External links

edit- Welcome To 'Allar, Palestine Remembered

- 'Allar, Zochrot

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 17: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Allar, from the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center

- Allar, from Baheth for Studies.

- Demarcation of Forest Lands, Government of Palestine, November 1932