Dej (Romanian pronunciation: [deʒ]; Hungarian: Dés; German: Desch, Burglos; Yiddish: דעעש Desh) is a municipality in Transylvania, Romania, 60 kilometres (37 mi) north of Cluj-Napoca, in Cluj County. It lies where the river Someșul Mic meets the river Someșul Mare. The city administers four villages: Ocna Dejului (Désakna), Peștera (Pestes), Pintic (Oláhpéntek), and Șomcutu Mic (Kissomkút).[4]

Dej | |

|---|---|

Dej Calvinist Church | |

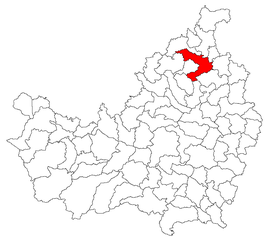

Location in Cluj County | |

| Coordinates: 47°05′14″N 23°48′19″E / 47.08722°N 23.80528°E | |

| Country | Romania |

| County | Cluj |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2020–2024) | Costan Morar[1] (PNL) |

| Area | 109.12 km2 (42.13 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 285 m (935 ft) |

| Population (2021-12-01)[2] | 31,475 |

| • Density | 290/km2 (750/sq mi) |

| Time zone | EET/EEST (UTC+2/+3) |

| Postal code | 405200 |

| Area code | +40 x64[3] |

| Vehicle reg. | CJ |

| Website | www |

The city lies at the crossroads of important railroads and highways linking it to Cluj-Napoca, Baia Mare, Satu Mare, Deda, Bistrița, and Vatra Dornei.

History

editArtifacts dating back to 5500 BC and belonging to the Starčevo–Körös–Criș culture, as well as artifacts dating back to the 15th century BC and belonging to the Wietenberg culture from the Bronze Age have been discovered on the territory of Dej.[5][6] Also in the Bronze Age, the exploitation of salt deposits in the area of today's city began and developed. During the Iron Age, the Geto-Dacian civilization arose and spread over a vast territory. The Someș Valley was an integral part of this historical evolution, as evidenced by archaeological discoveries in the area, such as the Dacian fortress at Dealul Florilor. After the Dacian Wars, Emperor Trajan transformed most of Dacia into a Roman province; the territory of the city became part of the province of Dacia Superior, and later Dacia Porolissensis.[5]

According to Gesta Hungarorum, Vlach political formations located in the north and northwest of Transylvania, led by Gelou, Glad, and Menumorut were conquered by the Hungarian tribes at the beginning of the tenth century. During the Menumorut voivodeship, the defense of the salt road was ensured by the fortresses from Ocna Dej and Cuzdrioara and the fortified points from Uriu and Urișor. The extension of the Kingdom of Hungary to the center and south of Transylvania was achieved with the help of Székely and German settlers. The first German settlers arrived in the Dej area in the years 1141–1143, entering from Satu Mare to Dej, Bistrița, Cluj, and Reghin. After leaving Holland and Flanders because of the floods of the sea, they settled in this region and founded the city of Dej.[5]

The city was first mentioned in 1214 as Dees, in 1236 as Deeswar, in 1310 as Deesvitta, in 1351 both Deés[7] and Deésvár occurred, the earlier has been used until eventually it was changed to Dés. It had a royal charter as a free city and was the capital of Szolnok-Doboka County.[7] In 1905, it had a Protestant church from the 15th century, and a tower from 16th century fortifications.[7] It was primarily a market town for local wines and other agricultural products.[8]

During the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 the city of Dés was the scene of military confrontations between units of the Hungarian army and units of the Austrian army, which included Romanian border regiments and Romanian peasants, under the command of colonel Karl von Urban. The biggest battle for control of Dés took place on 24 November 1848 in the Bungăr forest, and continued on the territory of the city. The Hungarian forces led by major Miklós Katona were put on the run by Von Urban, towards Nagybánya. More than 150 people fell in this battle; in their memory, the monument "The Sleeping Lion" was erected in 1889.[5]

The 19th century was a period of profound urban transformation and modernization works for the city, including the building of the County Prefecture, the City Hall, the Rudolf Hospital, the Palace of Justice, the Greek Catholic Church, the theater, the army barracks, and the "Andrei Mureșanu” High School.[5] In 1882, the Cluj–Apahida–Dej railway line was opened, with an extension to Ocna Dej, while in 1910 the Ferdinand mine was electrified.[9] The Dej Prison, located in the northern part of the town, was completed in 1894.

On 1 December 1918, eleven delegates from Dej took part in the Romanian National Assembly in Alba Iulia, which proclaimed the union of Transylvania with Romania. In the aftermath of World War I and the ensuing Hungarian–Romanian War, the Romanian Army entered the city on 21 December 1918, and later the city became part of Romania. The interwar period brought important transformations to the city of Dej that allowed its development and modernization under the leadership of its mayor, Cornel Pop, who assumed the position in May 1920. From 1925 to 1938, the city was the county seat of Someș County, after which it became part of Ținutul Crișuri.[5]

In the wake of the Second Vienna Award of August 30, 1940, the territory of Northern Transylvania (of which the city of Dej was part) reverted to the Kingdom of Hungary. On September 8, 1940, the Hungarian administration was installed in Dej, and proceeded to take discriminatory measures against Romanians and Jews, forcing many Romanians to take refuge in Romania.[5] In 1944 began the drama of the Jewish population in what was then Szolnok-Doboka County and its capital, Dés (Dej). Following several decrees of the Hungarian government and high-level consultations at a meeting on April 26 with László Endre in Szatmárnémeti (Satu Mare), it was decided to exterminate the Jews.[10] On May 3, the city authorities launched the action of ghettoization of Jews in the Bungăr forest, where 3,700 Jews from Dej and 4,100 Jews from other localities in the county were imprisoned. During the operation of the Dej ghetto, Jews were mistreated, tortured, and starved. The deportation of the Jews to the Nazi death camps was done with freight wagons, in three stages: the first transport on May 28 when 3,150 Jews were deported; the second on June 6, when 3,360 Jews were deported; the third on June 8, when the last 1,364 Jews were deported. Most of those deported were exterminated in the Auschwitz–Birkenau camp, with just over 800 deportees surviving.[5]

Towards the end of World War II, Romanian and Soviet armies entered the city on October 15, 1944. The territory of Northern Transylvania remained under Soviet military administration until March 9, 1945, after the appointment of Petru Groza as Prime Minister. After the elections of November 1946, residents of villages near Dej revolted against the falsification of the election results by the communist authorities and launched the first revolt against the new regime, being stopped by armed troops at the Someș bridge. The name of the city was related to the name of the first Romanian Communist Party leader, Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej who lived here in 1931 and worked at the railway station. When he became the de facto ruler of the country, Gheorghe Gheorghiu officially took the name of the city and supported the economic development of the locality. The communist regime brought with it fundamental transformations in the political, administrative and economic life of the city. Many previous leaders fell victim to the regime, as happened with the former mayor, Cornel Pop, who died in Văcărești prison in 1953. Another personality, ex-Prime Minister Alexandru Vaida-Voevod, a native of nearby Bobâlna, was arrested in March 1945 by the dreaded Securitate and died under house arrest in 1950.[5]

In December 1950, Someș County was abolished, and Dej District was organized in its place within the Cluj Region. Following the administrative reform of 1968, the city of Dej was declared a municipality within Cluj County. A tragic event in the history of the city were the catastrophic floods of May 1970, when all the low areas of the city were under water and 6 people drowned. After the Romanian Revolution of 1989, state-owned enterprises were privatized, an environment for developing a market economy was created, new production units with domestic and foreign capital were set up, and many small and medium-sized enterprises emerged in Dej. The educational institutions, the municipal hospital, the cultural institutions were modernized, new churches were built, and the infrastructure of the city was updated.[5]

Demographics

edit| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1910 | 11,452 | — |

| 1930 | 15,110 | +31.9% |

| 1948 | 14,681 | −2.8% |

| 1956 | 19,281 | +31.3% |

| 1966 | 26,984 | +40.0% |

| 1977 | 32,345 | +19.9% |

| 1992 | 41,216 | +27.4% |

| 2002 | 38,478 | −6.6% |

| 2011 | 33,497 | −12.9% |

| 2021 | 31,475 | −6.0% |

| Source: Census data | ||

At the 2021 Romanian census, Dej had a population of 31,475, a drop of 6% from the previous census.[11] At the 2011 census, there were 33,497 people living within the city; of those, 81.8% were ethnic Romanians, while 11.3% were ethnic Hungarians, 1.0% Roma, and 0.1% others.[12]

Natives

editGallery

edit-

Dej in 1902

-

The City Hall

-

City Square at Night

-

Avram Iancu Street

-

Synagogue in Dej

-

The Roman Catholic Church

-

Greek-Catholic Church in 1 Mai

-

Andrei Mureșanu National College

References

edit- ^ "Results of the 2020 local elections". Central Electoral Bureau. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Populaţia rezidentă după grupa de vârstă, pe județe și municipii, orașe, comune, la 1 decembrie 2021" (XLS). National Institute of Statistics.

- ^ x indicates the telephone operator: 2 for Romtelecom and 3 for other landline operators

- ^ "Despre Dej". primariadej.ro (in Romanian). Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Preistoria și antichitatea la confluența Someșurilor". primariadej.ro (in Romanian). Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- ^ Isac, Dan; Gogâltan, Florin; Călian, Livia; Barb, Raluca (2008). Contribuții arheologice la istoria orașului Dej, Cluj-Napoca (in Romanian). Cluj-Napoca: Editura Mega. ISBN 978-973-1868-31-8. OCLC 612886575. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Deés". Austria-Hungary: Including Dalmatia and Bosnia; Handbook for Travellers. Karl Baedeker. 1905. p. 406.

- ^ Ritter, Carl (1874). "Deés". Geographisch-statistisches Lexikon über die Erdteile, Länder, Meere, Buchten, Häfen, Seen, Flüsse, Inseln, Gebirge, Staaten, Städte, Flecken, Dörfer, Weiler, Bäder, Bergwerke, Kanäle etc (in German). Wigand. p. 375.

- ^ "Salina Ocna Dej – Istoric". www.salinaocnadej.ro (in Romanian). Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- ^ "Ghetouri" [Ghettoes] (in Romanian). Northern Transylvania Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- ^ "Populația rezidentă după grupa de vârstă, pe județe și municipii, orașe, comune, la 1 decembrie 2021" (in Romanian). INSSE. 31 May 2023.

- ^ Tab8. Populația stabilă după etnie – județe, municipii, orașe, comune, 2011 census results, Institutul Național de Statistică, accessed 17 February 2020.