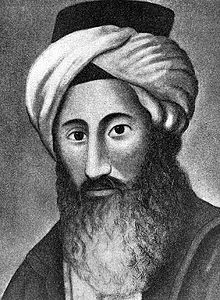

Haim Yosef David Azulai ben Yitzhak Zerachia (1724 – 1 March 1806) (Hebrew: חיים יוסף דוד אזולאי), commonly known as the Hida (also spelled Chida,[1] the acronym of his name, חיד"א), was a Jerusalem born rabbinical scholar, a noted bibliophile, and a pioneer in the publication of Jewish religious writings. He is considered "one of the most prominent Sephardi rabbis of the 18th century".[2]

Haim Yosef David Azulai | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal | |

| Born | 1724 |

| Died | 1 March 1806 (aged 81–82) |

| Religion | Judaism |

| Nationality | |

| Children | Raphael Isaiah Azulai, Abraham Azulai |

| Signature |  |

| Position | hv |

| Buried | Har HaMenuchot, Jerusalem (1960) |

Azulai embarked on two extensive fundraising missions for the Jewish community in Hebron. His first journey, spanning 1753–1757, crossed Italy and German lands, reaching Western Europe and London. A second trip, between 1772–1778, saw him travel through Tunisia, Italy, France, and Holland. Following his travels, Azulai settled in the Italian port city of Livorno, a major center of Sephardic Jewish life. He remained there until his death in 1806.[2]

The Hida's intact and published travel diaries, similarly to those of Benjamin of Tudela, provide a comprehensive first hand account of Jewish life and historical events throughout the Europe and Near East of his day.

Some have speculated that his family name, Azulai, is an acronym based on being a Kohen: אשה זנה וחללה לא יקחו (Leviticus, 21:7), a biblical restriction on whom a Kohen may marry.

Biography

editAzulai was born in Jerusalem, where he received his education from some local prominent scholars. He was the scion of a prominent rabbinic family, the great-great-grandson of Moroccan Rabbi Abraham Azulai.[3] The Yosef part of his name came from his mother's father, Rabbi Yosef Bialer, a German scholar.[4]

His main teachers were the Yishuv haYashan rabbis Isaac HaKohen Rapoport, Shalom Sharabi, and Haim ibn Attar (the Ohr HaHaim) as well as Jonah Nabon. At an early age he showed proficiency in Talmud, Kabbalah, and Jewish history, and "by the age of 12 he was already composing chiddushim on Hilchos Melichah."[citation needed]

In 1755, he was—on the basis of his scholarship—elected to become an emissary (shaliach) for the small Jewish community in the Land of Israel, and he would travel around Europe extensively, making an impression in every Jewish community that he visited. According to some records, he left the Land of Israel three times (1755, 1770, and 1781), living in Hebron in the meantime. His travels took him to Western Europe, North Africa, and—according to legend—to Lithuania, where he met the Vilna Gaon.[citation needed]

In 1755 he was in Germany, where he met the Pnei Yehoshua,[5] [6] who on the basis of prior written communication confirmed Hida's identity. In 1764 he was in Egypt, and in 1773 he was in Tunisia, Morocco, and Italy. He seems to have remained in the latter country until 1777, most probably occupied with the printing of the first part of his biographical dictionary, Shem HaGedolim, (Livorno, 1774), and with his notes on the Shulhan Aruch, entitled Birke Yosef, (Livorno, 1774–76). In 1777 he was in France, and in 1778 in Holland. Wherever he went, he would examine collections of manuscripts of rabbinic literature, which he later documented in his Shem HaGedolim.

On 28 October 1778 he married, in Pisa, his second wife, Rachel; his first wife, also Rachel, had died in 1773. Noting this event in his diary, he adds the wish that he may be permitted to return to the Land of Israel. This wish seems not to have been realized. In any event, he remained in Leghorn (Livorno), occupied with the publication of his works, and died there twenty-eight years later in 1806 (Friday night, 11 Adar 5566, Shabbat Zachor).[7][4][5] He had been married twice; he had two sons by the names of Abraham and Raphael Isaiah Azulai.

Reburial in Israel

editIn 1956,[8] the 150th anniversary of Hida's death, Israel's Chief Rabbi Yitzhak Nissim[9] began work on a plan[10] to reinter Hida in Israel. This included getting the approval and cooperation of the Leghorn Jewish community, acquiring a special 600 square meter plot on Har Hamenuchot, and constructing an ohel over the grave. On Tuesday, 20 Iyar 5720 (17 May 1960), 154 years after his Petira, Hida's final written wish, to return to Israel, "came true."

His early scholarship

editWhile being a strict Talmudist, and a believer in the Kabbalah, his studious habits and exceptional memory awakened in him an interest in the history of rabbinical literature.

He accordingly began at an early age a compilation of passages in rabbinical literature in which dialectic authors had tried to solve questions that were based on chronological errors. This compilation, which he completed at age 16,[11] he called העלם דבר (Some Oversights); it was never printed.

Azulai's scholarship made him so famous that in 1755 he was chosen as meshulach, (emissary), an honor bestowed on such men only as were, by their learning, well fitted to represent the Holy Land in Europe, where the people looked upon a rabbi from the land of Israel as a model of learning and piety.

Azulai's literary activity is of an astonishing breadth. It encompasses every area of rabbinic literature: exegesis, homiletics, casuistry, Kabbalah, liturgics, and literary history. A voracious reader, he noted all historical references; and on his travels he visited the famous libraries of Italy and France, where he examined the Hebrew manuscripts.

His works

editAzulai was a prolific writer. His works range from a prayerbook he edited and arranged ('Tefillat Yesharim') to a vast spectrum of Halachic literature including a commentary on the Shulchan Aruch titled 'Birkei Yosef' which appears in most editions. While living and traveling in Italy, he printed many works, mainly in Livorno and Pisa but also in Mantua. The list of his works, compiled by Isaac ben Jacob, runs to seventy-one items; but some are named twice, because they have two titles, and some are only small treatises. The veneration bestowed upon him by his contemporaries was that given to a saint. He reports in his diary that when he learned in Tunis of the death of his first wife, he kept it secret, because the people would have forced him to marry at once. Legends printed in the appendix to his diary, and others found in Aaron Walden's Shem HaGedolim HeḤadash (compare also Ma'aseh Nora, pp. 7–16, Podgorica, 1899), prove the great respect in which he was held. Many of his works are still extant and studied today. His scope was exceptionally wide, from halakha (Birkei Yosef) and Midrash to his main historical work Shem HaGedolim. Despite his Sephardi heritage, he appears to have been particularly fond of the Chasidei Ashkenaz (a group of Medieval German rabbis, notably Judah the Chasid).

Shem HaGedolim

editHis historical notes were published in four booklets, comprising two sections, under the titles Shem HaGedolim[12] (The Name of the Great Ones), containing the names of authors, and Va'ad la-Ḥakhamim (Assembly of the Wise), containing the titles of works. This treatise has established for Azulai a lasting place in Jewish literature. It contains data that might otherwise have been lost, and it proves the author to have had a critical mind. By sound scientific methods he investigated the question of the genuineness of Rashi's commentary to Chronicles or to some Talmudic treatise (see "Rashi," in Shem HaGedolim). However, he does assert that Rashi indeed is the author of the "Rashi" commentary on Neviim and Ketuvim, contrary to some others'[who?] opinions.

Nevertheless, he firmly believed that Haim Vital had drunk water from Miriam's well, and that this fact enabled him to receive, in less than two years, the whole Kabbalah from the lips of Isaac Luria (see "Ḥayyim Vital," in Shem HaGedolim). Azulai often records where he has seen in person which versions of certain manuscripts were extant.

Bibliography

editA complete bibliographical list of his works is found in the preface to Benjacob's edition of Shem HaGedolim, Vilna, 1852, and frequently reprinted;

- Eliakim Carmoly, in the edition of Shem HaGedolim, Frankfort-on-the-Main, 1843;

- Fuenn, Keneset Yisrael, p. 342;

- Hazan, Hama'alot li-Shelomoh, Alexandria, 1894;

- Aaron Walden, Shem HaGedolim HeChadash, 1879;

- The diary Ma'agal Tob, edited by Elijah Benamozegh, Leghorn, 1879;

- Heimann Joseph Michael, Or ha-chayyim, No. 868.

His role as Shadar

editThe Hida served the role of shadar (shaliach derabanan), or emissary, for the Jewish community of Hebron. He left Israel twice on five-year-long fundraising missions that took him as far west as Tunisia and as far north as Great Britain and Amsterdam. The Hida collected money on behalf of the Jewish communities in Israel who suffered from poverty and persecution.[13]

The Hida, like many emissaries, was a qualified and highly regarded personality who was chosen to represent his community. A shadar often had to be able to arbitrate matters of Jewish law for the local Jewish communities Ideally, emissaries were multi-lingual so that they could communicate with both Jew and Gentile along the way. Emissaries had to be willing to undertake dangerous journeys mission that would separate them away from their families for so long. One in ten emissaries sent abroad for these fundraising missions never made it back alive. Emissaries would often divorce their wives before leaving, so that if they died along the way and their deaths could not be verified, their wives would be able to legally remarry. If they returned safely from their journey, they would remarry their wives, who would sometimes wait as long as five years for their husbands to return from their mission.

Moreover, the Hida records numerous instances of miraculous survival and dangerous threats of his day, among them, close scrapes with the Russian Navy during its support of the Ali Bey uprising against the Turks, the danger of boarding and worse by the Knights of Malta, the hostility of the English government officials towards anyone entering the country from France or Spain, as well as those aforementioned countries' wrath against someone crossing back over from their hated enemy, England, and the daily danger of running into various anti-semitic locals and nobles throughout mainland Europe (especially Germany).

Travelogue: Ma'gal Tov

editAzulai authored a detailed travelogue recounting his two journeys to Europe.[2] The travelogue documents Azulai's encounters with various communities, rare books and manuscripts, and the challenges of overseas travel, including storms, pirates, custom officials, and occasional hostility from non-Jewish inkeepers.[2] Likely intended for personal use, the travelogue was first printed in the 1930s by Aron Freimann based on the original autograph manuscript.[2]

In his travelogue, Azulai also shows an interest in tourist attractions, visiting landmarks such as the Leaning Tower of Pisa, the Boboli Gardens of Florence, the Palace of Versailles, and the Tower of London. He also climbed the Campanile in Venice for a panoramic view of the city and explored destinations like the new promenade in Nizza, an ancient temple in southern France, and the natural science museum in Amsterdam.[2]

References

edit- ^ Paretzky, Zev T. The Chida: Rabbi Chaim Yosef David Azulai: His life and the turbulent times in which he lived. Targum Press, 1998.

- ^ a b c d e f Lehmann, M. B. (2007). " Levantinos" and Other Jews: Reading HYD Azulai's Travel Diary. Jewish Social Studies, 2

- ^ Shem HaGedolim, Livorno 1774, p. 11b. (Available on Hebrewbooks.com.) In this passage, Haim Yosef David gives the following genealogy: Abraham Azulai → Isaac Azualai → Isaiah Azulai → Isaac Zerahiah Azulai → Haim Yosef David Azulai.

- ^ a b "The human side of the Chida". 24 March 2013.

- ^ a b "This Day in History – 11 Adar/March 2". Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ^ An experience Hida described in his Shem HaGeDoLim as "I was fortunate as a young man to spend time with" ... Rabbi Pinches Friedman (12 August 2011). "Shvilei Pinches".

- ^ 'Codex Judaica', Mattis Kantor, p.259

- ^ Dr. Aaron Arend. "You shall carry up my bones from here (Parashat Beshalah 5760/2000)". Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ^ "Story about the Chida's burial facilitated by Rav Mordechai Eliyahu zt"l". 17 June 2010. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- ^ Azoulay, Yehuda (April 2010). "From Italy to Jerusalem". Community Magazine. Brooklyn. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ^ Mindel, Nissan. "Rabbi Chaim Joseph David Azulai". Kehot Publication Society. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- ^ Cowley, Arthur Ernest (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 176.

- ^ Paretzky, Zev T. The Chida: Rabbi Chaim Yosef David Azulai: His life and the turbulent times in which he lived. Targum Press, 1998.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Azulai, Azulay". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

- Biography of Rabbi Azulai - A Legend of Greatness - The Life & Time of Hacham Haim Yosef David Azoulay by Yehuda Azoulay