The trill (or shake, as it was known from the 16th until the early 20th century) is a musical ornament consisting of a rapid alternation between two adjacent notes, usually a semitone or tone apart, which can be identified with the context of the trill[2] (compare mordent and tremolo). It is sometimes referred to by the German Triller, the Italian trillo, the French trille or the Spanish trino. A cadential trill is a trill associated with each cadence. A groppo or gruppo is a specific type of cadential trill which alternates with the auxiliary note directly above it and ends with a musical turn as additional ornamentation.[3][4]

A trill provides rhythmic interest, melodic interest, and—through dissonance—harmonic interest.[5] Sometimes it is expected that the trill will end with a turn (by sounding the note below rather than the note above the principal note, immediately before the last sounding of the principal note), or some other variation. Such variations are often marked with a few appoggiaturas following the note bearing the trill indication.

Notation

editIn most modern musical notation, a trill is generally indicated with the letters tr (or sometimes simply t)[2] above the trilled note. This has sometimes been followed by a wavy line, and sometimes, in the baroque and early classical periods,[2] the wavy line was used on its own. In those times the symbol was known as a chevron.[6] The following two notations are equivalent:

Both the "tr" and the wavy line are necessary for clarity when the trill is expected to be applied to more than one note (or to tied notes). Also, when attached to a single notehead in one part that corresponds to smaller note values in another part, it leaves no room for doubt if both the letter and line are used.

The usual way of executing a trill, known as a diatonic trill, is to rapidly alternate between the written note and the one directly above it in the given scale (unless the trill symbol is modified by an accidental, understood to apply to the added note above; this is a chromatic trill).

Listen to an example of a short passage ending on a trill. The first time, the passage ends in a trill, and the second, it does not.

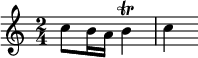

This is an alternative trill:

These examples are approximations of how trills may be executed. In many cases, the rate of the trill does not remain constant as indicated here, but starts slower and increases. Whether it is played this way or not is largely a matter of taste.

The number of alternations between the notes played in a trill can vary according to the length of the notated note. At slower tempos, a written note lasts longer, meaning more notes can be played in the trill applied to it; but at fast tempi and with a short note, a trill may be reduced to nothing more than the indicated note, the note above it, and the indicated note again, in which case it resembles an upper mordent.

Trills may also be started on the note above the notated note (the auxiliary note). Additionally, a trill is often ended by playing the note below the notated one, followed by the note itself.

In specific styles

editIn baroque music

editThe taste for cadences (like the taste for sequences), and with them the obligation to bring in their implied cadential trills, was... ingrained in baroque musicianship... For those who do not like cadences, sequences, and cadential trills, baroque music is not the scene.

— Robert Donington, Baroque Music, Style and Performance[1]

Hugo Riemann described the trill as "the chief and most frequent" of all musical embellishments.[8] In the baroque period, a number of signs indicating specific patterns with which a trill should be begun or ended were used. In the Klavierbüchlein für Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, Johann Sebastian Bach lists a number of these signs together with the correct way to interpret them. Unless one of these specific signs is indicated, the details of how to play the trill are up to the performer. In general, however, trills in this era are executed beginning on the auxiliary note, before the written note, often producing the effect of a harmonic suspension which resolves to the principal note. But, if the note preceding the ornamented note is itself one scale degree above the principal note, then the dissonant note has already been stated, and the trill typically starts on the principal note.

Several trill symbols and techniques common in the Baroque and early Classical era have fallen entirely out of use, including for instance the brief Pralltriller, represented by a very brief wavy line, referred to by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach in his Essay on the True Art of Playing Keyboard Instruments (Versuch) (1753–1762).

Beyond the baroque era, specific signs for ornamentation are very rare. Continuing through the time of Mozart, the default expectations for the interpretation of trills continued to be similar to those of the baroque. In music after the time of Mozart, the trill usually begins on the principal note.

All of these are only rules of thumb, and, together with the overall rate of the trill and whether that rate is constant or variable, can only be determined by considering the context in which the trill appears, and is usually to a large degree a matter of opinion with no single "right" way of executing the ornament.

On specific instruments

editThe trill is frequently found in classical music for all instruments, although it is more easily executed on some than others. For example, while it is relatively easy to produce a trill on the flute, the proper execution on brass instruments requires higher skill and is produced by quickly alternating partials. While playing a trill on the piano the pianist may find that it becomes increasingly difficult to execute a trill including the weak fingers of the hand (3, 4 and 5), with a trill consisting of 4 and 5 being the hardest. On the guitar, a trill can be either a series of hammer-ons and pull-offs (generally executed using just the fingers of the fretting hand, but players can use both hands), or a rapidly plucked pair of notes on adjacent strings, known as a cross-string trill. Trill keys are used to rapidly alternate between a note and an adjacent note often in another register on woodwind instruments. On the bowed instruments, the violin and the viola in particular, the trill is relatively easy to execute, with a straightforward bowing and the trill involving the oscillation of just one finger against the main note which is stopped by the finger behind, or more rarely, the open string.

On brass instruments

editTrills may be performed on valveless brass instruments by rapidly slurring between two adjacent notes by means of the embouchure – this is colloquially known as a "lip trill." This was a common practice on the natural trumpets and natural horns of the Baroque/Classical era. However the lip trill is often still used in the modern French horn in places where the harmonics are only a tone apart (though this can be difficult for inexperienced players). Such trills are also a stylistic feature of jazz music, particularly in trumpet parts.

Vocal trills

editVocal music of the classical tradition has included a variety of ornaments known as trills since the time of Giulio Caccini. In the preface to his Le nuove musiche, he describes both the "shake" (what is commonly known today as the trill) and the "trill" (now often called a Baroque or Monteverdi trill). However, by the time of the Italian bel canto composers such as Rossini, Donizetti and Bellini, the rapid alternation between two notes that Caccini describes as a shake was known as a trill and was preferred.

Coloratura singers, particularly the high-voiced sopranos and tenors, are frequently required to trill not only in the works of these composers but in much of their repertoire. Soprano Dame Joan Sutherland was particularly famed for the evenness and rapidity of her trill, and stated in an interview that she "never really had to learn how to trill".[9] The trill is usually a feature of an ornamented solo line, but choral or chorus trills do appear.

Despite the trill being written in many works for voice, a singer with an even, rapid trill is a rarity. Opinion is divided as to if and how well a trill can be taught or learnt, though mezzo-soprano Marilyn Horne frequently stated that she gained her trill by a commonly taught exercise, alternating between two notes, starting slowly and increasing velocity over time.[10] The director of the Rossini Opera Festival, Alberto Zedda has opined in interview that the "widespread technical deficiency",[11] the inability to trill, is a source of "frustration and anguish". In fact, whole performances and recordings, especially of bel canto works, have been judged based on performance—or lack thereof—of trills, especially trills written in the score as opposed to trills in a cadenza or variation.[citation needed]

Trillo

editThe word trillo is sometimes used to mean the same as trill. However, in early music some refer to a related ornament specifically called trillo:

Trillo is the least familiar of the vocal maneuvers, and, in present day usage, is performed either on a single note or as a technique for executing rapid scale-like passages. Perceptually, it is heard as a rhythmic interruption, or near interruption, of phonation that typically begins slowly with individual pulses separated by a short silent period and then often increases in rate to something resembling a vocal imitation of machine gun firing, albeit without the accompanying cacophony.[12]

Montserrat Caballé was a known exponent of the trillo, as can be heard from her famous 1974 Norma.

See also

editFootnotes

edit- ^ a b Donington, Robert (1982). Baroque Music, Style and Performance, p. 126. ISBN 978-0-393-30052-9.

- ^ a b c Taylor, Eric. The AB Guide to Music Theory: Part I, p. 92.

- ^ "Groppo (It.)". Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press. 2002. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.48830.(subscription required)

- ^ "Gruppo (It.)". Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press. 2002. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.53644.(subscription required)

- ^ Nurmi, Ruth (1974). A Plain & Easy Introduction to the Harpsichord, p. 145. ISBN 9780810818866.

- ^ Neumann, Frederick (1978). Ornamentation in Baroque and Post-baroque Music: With Special Emphasis on J. S. Bach, p. 581. Princeton. ISBN 9780691027074.

- ^ Taylor, Franklin. Bach: Short Preludes & Fugues, p. 1.

- ^ Mansfield, Orlando (August 1924). "The Story of the Trill, or Shake". The Etude. Theodore Presser Company: 521.

- ^ Interview with Dame Joan Sutherland and Richard Bonynge on YouTube.

- ^ Interview with Dame Joan Sutherland and Marilyn Horne on YouTube.

- ^ Hastings, Stephen. "Taking the Pulse of Pesaro". OPERA NEWS. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ^ Hakes, Jean; Shipp, Thomas; Doherty, E. Thomas (1988). "Acoustic characteristics of vocal oscillations: Vibrato, exaggerated vibrato, trill, and trillo". Journal of Voice. 1 (4). Raven Press: 326–331. doi:10.1016/S0892-1997(88)80006-7.

References

edit- Taylor, Eric. "The AB Guide to Music Theory: Part I", England: The Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music (Publishing) Ltd., 1989. ISBN 1-85472-446-0

- Taylor, Franklin "Bach: Short Preludes & Fugues", London, England: Augener Ltd., 1913. No. 8020a

- The Trill in the Classical Period (1750–1820)

External links

edit- Trill fingering diagrams for the recorder, WFG.Woodwind.Org.

- Trill fingering diagrams for the flute/piccolo, WFG.Woodwind.Org.

- Trill fingering diagrams for the oboe, WFG.Woodwind.Org.

- Trill fingering diagrams for the boehm-system clarinet, WFG.Woodwind.Org.

- Trill fingering diagrams for the saxophone, WFG.Woodwind.Org.

- Trill fingering diagrams for the bassoon, WFG.Woodwind.Org.