A carbonate is a salt of carbonic acid, H2CO3,[2] characterized by the presence of the carbonate ion, a polyatomic ion with the formula CO2−3. The word "carbonate" may also refer to a carbonate ester, an organic compound containing the carbonate group O=C(−O−)2.

Carbonate anion

| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Carbonate | |

| Systematic IUPAC name

Trioxidocarbonate[1]: 127 | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| CO2−3 | |

| Molar mass | 60.008 g·mol−1 |

| Conjugate acid | Bicarbonate |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

The term is also used as a verb, to describe carbonation: the process of raising the concentrations of carbonate and bicarbonate ions in water to produce carbonated water and other carbonated beverages – either by the addition of carbon dioxide gas under pressure or by dissolving carbonate or bicarbonate salts into the water.

In geology and mineralogy, the term "carbonate" can refer both to carbonate minerals and carbonate rock (which is made of chiefly carbonate minerals), and both are dominated by the carbonate ion, CO2−3. Carbonate minerals are extremely varied and ubiquitous in chemically precipitated sedimentary rock. The most common are calcite or calcium carbonate, CaCO3, the chief constituent of limestone (as well as the main component of mollusc shells and coral skeletons); dolomite, a calcium-magnesium carbonate CaMg(CO3)2; and siderite, or iron(II) carbonate, FeCO3, an important iron ore. Sodium carbonate ("soda" or "natron"), Na2CO3, and potassium carbonate ("potash"), K2CO3, have been used since antiquity for cleaning and preservation, as well as for the manufacture of glass. Carbonates are widely used in industry, such as in iron smelting, as a raw material for Portland cement and lime manufacture, in the composition of ceramic glazes, and more. New applications of alkali metal carbonates include: thermal energy storage,[3][4] catalysis[5] and electrolyte both in fuel cell technology[6] as well as in electrosynthesis of H2O2 in aqueous media.[7]

Structure and bonding

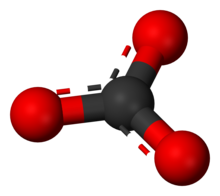

editThe carbonate ion is the simplest oxocarbon anion. It consists of one carbon atom surrounded by three oxygen atoms, in a trigonal planar arrangement, with D3h molecular symmetry. It has a molecular mass of 60.01 g/mol and carries a total formal charge of −2. It is the conjugate base of the hydrogencarbonate (bicarbonate)[8] ion, HCO−3, which is the conjugate base of H2CO3, carbonic acid.

The Lewis structure of the carbonate ion has two (long) single bonds to negative oxygen atoms, and one short double bond to a neutral oxygen atom.

This structure is incompatible with the observed symmetry of the ion, which implies that the three bonds are the same length and that the three oxygen atoms are equivalent. As in the case of the isoelectronic nitrate ion, the symmetry can be achieved by a resonance among three structures:

This resonance can be summarized by a model with fractional bonds and delocalized charges:

Chemical properties

editMetal carbonates generally decompose on heating, liberating carbon dioxide leaving behind an oxide of the metal.[2] This process is called calcination, after calx, the Latin name of quicklime or calcium oxide, CaO, which is obtained by roasting limestone in a lime kiln:

- CaCO3 → CaO + CO2

As illustrated by its affinity for Ca2+, carbonate is a ligand for many metal cations. Transition metal carbonate and bicarbonate complexes feature metal ions covalently bonded to carbonate in a variety of bonding modes.

Lithium, sodium, potassium, rubidium, caesium, and ammonium carbonates are water-soluble salts, but carbonates of 2+ and 3+ ions are often poorly soluble in water. Of the insoluble metal carbonates, CaCO3 is important because, in the form of scale, it accumulates in and impedes flow through pipes. Hard water is rich in this material, giving rise to the need for infrastructural water softening.

Acidification of carbonates generally liberates carbon dioxide:

- CaCO3 + 2 HCl → CaCl2 + CO2 + H2O

Thus, scale can be removed with acid.

In solution the equilibrium between carbonate, bicarbonate, carbon dioxide and carbonic acid is sensitive to pH, temperature, and pressure. Although di- and trivalent carbonates have low solubility, bicarbonate salts are far more soluble. This difference is related to the disparate lattice energies of solids composed of mono- vs dianions, as well as mono- vs dications.

In aqueous solution, carbonate, bicarbonate, carbon dioxide, and carbonic acid participate in a dynamic equilibrium. In strongly basic conditions, the carbonate ion predominates, while in weakly basic conditions, the bicarbonate ion is prevalent. In more acid conditions, aqueous carbon dioxide, CO2(aq), is the main form, which, with water, H2O, is in equilibrium with carbonic acid – the equilibrium lies strongly towards carbon dioxide. Thus sodium carbonate is basic, sodium bicarbonate is weakly basic, while carbon dioxide itself is a weak acid.

Organic carbonates

editIn organic chemistry a carbonate can also refer to a functional group within a larger molecule that contains a carbon atom bound to three oxygen atoms, one of which is double bonded. These compounds are also known as organocarbonates or carbonate esters, and have the general formula R−O−C(=O)−O−R′, or RR′CO3. Important organocarbonates include dimethyl carbonate, the cyclic compounds ethylene carbonate and propylene carbonate, and the phosgene replacement, triphosgene.

Buffer

editThree reversible reactions control the pH balance of blood and act as a buffer to stabilise it in the range 7.37–7.43:[9][10]

- H+ + HCO−3 ⇌ H2CO3

- H2CO3 ⇌ CO2(aq) + H2O

- CO2(aq) ⇌ CO2(g)

Exhaled CO2(g) depletes CO2(aq), which in turn consumes H2CO3, causing the equilibrium of the first reaction to try to restore the level of carbonic acid by reacting bicarbonate with a hydrogen ion, an example of Le Châtelier's principle. The result is to make the blood more alkaline (raise pH). By the same principle, when the pH is too high, the kidneys excrete bicarbonate (HCO−3) into urine as urea via the urea cycle (or Krebs–Henseleit ornithine cycle). By removing the bicarbonate, more H+ is generated from carbonic acid (H2CO3), which comes from CO2(g) produced by cellular respiration.[11]

Crucially, a similar buffer operates in the oceans. It is a major factor in climate change and the long-term carbon cycle, due to the large number of marine organisms (especially coral) which are made of calcium carbonate. Increased solubility of carbonate through increased temperatures results in lower production of marine calcite and increased concentration of atmospheric carbon dioxide. This, in turn, increases Earth temperature. The amount of CO2−3 available is on a geological scale and substantial quantities may eventually be redissolved into the sea and released to the atmosphere, increasing CO2 levels even more.[12]

Carbonate salts

edit- Carbonate overview:

Presence outside Earth

editIt is generally thought that the presence of carbonates in rock is strong evidence for the presence of liquid water. Recent observations of the planetary nebula NGC 6302 show evidence for carbonates in space,[13] where aqueous alteration similar to that on Earth is unlikely. Other minerals have been proposed which would fit the observations.

Small amounts of carbonate deposits have been found on Mars via spectral imaging [14] and Martian meteorites also contain small amounts. Groundwater may have existed at Gusev[15] and Meridiani Planum.[16]

See also

edit- Cap carbonates

- Orthocarbonic acid, H4CO4, or C(OH)4, a hypothetic unstable molecule

- Oxalate

- Peroxocarbonate

- Sodium percarbonate

References

edit- ^ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (2005). Nomenclature of Inorganic Chemistry (IUPAC Recommendations 2005). Cambridge (UK): RSC–IUPAC. ISBN 0-85404-438-8. Electronic version.

- ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Navarrete, N.; Nithiyanantham, U.; Hernández, L.; Mondragón, R. (2022-03-01). "K2CO3–Li2CO3 molten carbonate mixtures and their nanofluids for thermal energy storage: An overview of the literature". Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells. 236: 111525. doi:10.1016/j.solmat.2021.111525. hdl:10234/196651. ISSN 0927-0248. S2CID 245455194.

- ^ Lambrecht, Mickaël; García-Martín, Gustavo; de Miguel, María Teresa; Lasanta, María Isabel; Pérez, Francisco Javier (2023-08-01). "Temperature dependence of high-temperature corrosion on nickel-based alloy in molten carbonates for concentrated solar power applications". Corrosion Science. 220: 111262. Bibcode:2023Corro.22011262L. doi:10.1016/j.corsci.2023.111262. ISSN 0010-938X.

- ^ Hayakawa, Mamiko; Tashiro, Kenshiro; Sumiya, Daiki; Aoyama, Tadashi (2023-06-18). "Simple methods for the synthesis of N -substituted acryl amides using Na 2 CO 3 /SiO 2 or NaHSO 4 /SiO 2". Synthetic Communications. 53 (12): 883–892. doi:10.1080/00397911.2023.2201454. ISSN 0039-7911. S2CID 258197818.

- ^ Milewski, Jarosław; Wejrzanowski, Tomasz; Fung, Kuan-Zong; Szczśniak, Arkadiusz; Ćwieka, Karol; Tsai, Shu-Yi; Dybiński, Olaf; Skibiński, Jakub; Tang, Jhih-Yu; Szabłowski, Łukasz (2021-04-21). "Supporting ionic conductivity of Li2CO3/K2CO3 molten carbonate electrolyte by using yttria stabilized zirconia matrix". International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. International Workshop of Molten Carbonates & Related Topics 2019 (IWMC2019). 46 (28): 14977–14987. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.12.073. ISSN 0360-3199. S2CID 234180559.

- ^ Anodic generation of hydrogen peroxide in continuous flow, DOI: 10.1039/D2GC02575B (Paper) Green Chem., 2022, 24, 7931-7940

- ^ Nomenclature of Inorganic Chemistry IUPAC Recommendations 2005 (PDF), IUPAC, p. 137, archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-05-18

- ^ "Chemical of the Week -- Biological Buffers". Archived from the original on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2010-09-05.

- ^ Acid–Base Regulation and Disorders at The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy Professional Edition

- ^ Silverthorn, Dee Unglaub (2016). Human physiology. An integrated approach (Seventh, Global ed.). Harlow, England: Pearson. pp. 607–608, 666–673. ISBN 978-1-292-09493-9.

- ^ IPCC (2019). "Summary for Policymakers" (PDF). IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate. pp. 3–35.

- ^ Kemper, F., Molster, F.J., Jager, C. and Waters, L.B.F.M. (2001) The mineral composition and spatial distribution of the dust ejecta of NGC 6302. Astronomy & Astrophysics 394, 679–690.

- ^ Fairén, Alberto G.; Fernández-Remolar, David; Dohm, James M.; Baker, Victor R.; Amils, Ricardo (September 2004). "Inhibition of carbonate synthesis in acidic oceans on early Mars". Nature. 431 (7007): 423–426. Bibcode:2004Natur.431..423F. doi:10.1038/nature02911. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 15386004.

- ^ Squyres, S. W.; et al. (2007). "Pyroclastic Activity at Home Plate in Gusev Crater, Mars" (PDF). Science. 316 (5825): 738–742. Bibcode:2007Sci...316..738S. doi:10.1126/science.1139045. hdl:2060/20070016011. PMID 17478719. S2CID 9687521. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-09-22.

- ^ Squyres, S. W.; et al. (2006). "Overview of the Opportunity Mars Exploration Rover Mission to Meridiani Planum: Eagle Crater to Purgatory Ripple" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. 111 (E12): n/a. Bibcode:2006JGRE..11112S12S. doi:10.1029/2006JE002771. hdl:1893/17165. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-08.