The 12-inch coastal defense gun M1895 (305 mm) and its variants the M1888 and M1900 were large coastal artillery pieces installed to defend major American seaports between 1895 and 1945. For most of their history they were operated by the United States Army Coast Artillery Corps. Most were installed on disappearing carriages, with early installations on low-angle barbette mountings. From 1919, 19 long-range two-gun batteries were built using the M1895 on an M1917 long-range barbette carriage. Almost all of the weapons not in the Philippines were scrapped during and after World War II.

| 12-inch gun M1895 | |

|---|---|

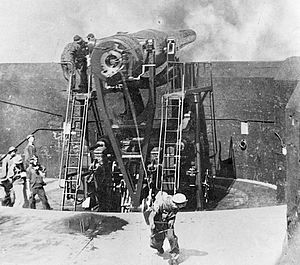

12-inch M1895 coastal defense gun being fired by lanyard | |

| Type | Coastal artillery |

| Place of origin | United States |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1895–1945 |

| Used by | United States Army |

| Wars | World War I, World War II |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Watervliet Arsenal |

| Designed | 1888 |

| Manufacturer | Watervliet Arsenal, Bethlehem Steel, possibly others |

| Variants | M1888, M1895, M1900 |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 115,000 pounds (52,163 kilograms) (M1895) |

| Length | 442.56 inches (11.241 meters) |

| Barrel length | 35 calibers (442.56 inches; 11.241 meters) |

| Shell | separate loading, 975 pounds (442 kg) AP, 1,070 pounds (490 kg) AP shot & shell[1] |

| Caliber | 12 in (305 mm) |

| Breech | Welin breech block |

| Carriage | M1891 gun lift, M1892 or M1897 barbette, M1896, M1897 or M1901 disappearing, M1917 long-range barbette from 1920[2] |

| Traverse | disappearing: 170° (varied with emplacement), long-range M1917 barbette: 360° (145° casemated), railway: 10° |

| Muzzle velocity | 2,250 feet per second (690 m/s)[3] |

| Maximum firing range | disappearing: 18,400 yards (16,800 m), long-range M1917 barbette: 30,100 yards (27,500 m), railway: 30,100 yards (27,500 m)[1] |

| Feed system | hand |

History

editIn 1885, William C. Endicott, President Grover Cleveland's secretary of war, was tasked with creating the Board of Fortifications to review seacoast defenses. The findings of the board illustrated a grim picture of existing defenses, and in its 1886 report recommended a massive $127 million construction program of breech-loading cannons, mortars, floating batteries, and submarine mines for some 29 locations on the US coastline. Most of the board's recommendations were implemented. Coast artillery fortifications built between 1885 and 1905 are often referred to as "Endicott Period" fortifications.

Watervliet Arsenal designed the gun and built the barrels. For several years, difficulties were encountered in building a disappearing carriage for the 12-inch gun. One alternative was the M1891 gun lift carriage, with the gun mounted on a large steam-powered elevator. Only one battery of this type was built, Battery Potter at Fort Hancock, New Jersey. When this proved to be too complex, guns were mounted on low-angle M1892 or M1897 barbette carriages. The M1897 carriage was actually an "altered gun lift" carriage, functionally equivalent to the barbette carriage. Eventually, the guns were mounted on M1896, M1897, or M1901 disappearing carriages designed by Bethlehem Steel; when the gun was fired, it dropped behind a concrete or earthen wall for protection from counter-battery fire.[4] Bethlehem later built barrels as well. Detailed descriptions of the M1888 weapon, disappearing carriage, and gun lift carriage are in the US Army's Artillery circular 1893, pp. 195–207. Detailed parts lists for the M1888 weapon and supporting equipment are in the Ordnance supply manual by George L. Lohrer, United States Army, Ordnance Dept, 1904, pp. 115–211.

After the Spanish–American War, the government wanted to protect American seaports in the event of war, and also protect newly gained territory, such as the Philippines and Cuba, from enemy attack. A new Board of Fortifications, under President Theodore Roosevelt's secretary of war, William Taft, was convened in 1905. Taft recommended technical changes, such as more searchlights, electrification, and, in some cases, less guns in particular fortifications. The seacoast forts were funded under the Spooner Act of 1902 and construction began within a few years and lasted into the 1920s. The defenses of the Philippines on islands in Manila Bay were built under this program.[5]

Railway mounting

editAfter the American entry into World War I, the army recognized the need for large-caliber railway guns for use on the Western Front. Among the weapons available were 45 12-inch guns, to be removed from fixed defenses or taken from spares. Twelve M1895 weapons were mounted on M1918 railway carriages (based on the French Batignolles mount) by mid-1919; it is unclear if any more were eventually mounted.[6][7] A detailed description of the railway mounting is given in Railway Artillery, Vol. I by Lt. Col. H. W. Miller.[8] The range of the railway weapon was 25,000 yards (23,000 m) at 38° elevation.[9] Like almost all US-made railway guns of World War I (the notable exception being the US Navy's 14"/50 caliber railway guns), these never left the US.[10] Although the twelve guns survived until early in World War II, they were not deployed. In 1941 they were declared "limited standard", and all but one were scrapped during the war.[7] The survivor was used for experimental purposes at the Naval Surface Warfare Center Dahlgren Division until it was transferred to the U.S. Army Ordnance Training and Heritage Center at Fort Lee, Virginia in the 2000s.

Long-range mounting

editAlso during World War I, it was recognized that naval guns were rapidly improving and longer-range weapons were needed. Fourteen two-gun and two one-gun batteries were constructed with M1895 guns on the new M1917 long-range barbette carriage,[11] which allowed an elevation of 35 degrees, compared to 15 degrees for the disappearing carriages. This increased the range from 18,400 yards (16,800 m) to 30,100 yards (27,500 m).[1] Eleven of these batteries were in the continental United States, with two in Panama, one in Hawaii, and two one-gun batteries at Fort Mills on Corregidor in the Philippines.[12][13] The guns were originally in open mounts with protected magazines, but most were casemated against air attack, beginning in 1940 as World War II approached the United States. However, the batteries in the Philippines were not casemated, as the 1923 Washington Naval Treaty prohibited further fortification of US and Japanese Pacific-area possessions, and in 1940–41 there was a lack of resources to do so. In some cases, an M1916 75 mm gun was mounted atop a 12-inch gun for subcaliber training.[14]

World War II

editAlong with other coast artillery weapons, the 12-inch guns in the Philippines saw action in the Japanese invasion in World War II. Since they were positioned against a naval attack, they were poorly sited to engage the Japanese (although the long-range batteries had 360° fire due to lack of casemates, the disappearing batteries had about 170° fire). Other limiting factors were that they had mostly armor-piercing ammunition, and the open mountings were vulnerable to air and high-angle artillery attack.

Three additional long-range casemated batteries were constructed during the war, at Fort Miles, Delaware, San Juan, Puerto Rico, and on Sullivan's Island near Fort Moultrie in the Harbor Defenses of Charleston, South Carolina. With the additional construction of 16-inch gun batteries at most harbor defenses, all guns on disappearing carriages were scrapped in 1943–44. The long-range batteries' guns were scrapped soon after the war ended.

M1895 12-inch coastal artillery batteries

edit| Name | Location | # | Model | Carriage | Built | Deactivated | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Battery Varnum | Fort Wetherill, Jamestown, RI | 2 | M1888 | barbette carriages | 1903 | 1943 | |

| Battery Wheaton | Fort Wetherill, Jamestown, RI | 2 | M1888 | disappearing carriages | 1908 | 1945 | |

| Battery Torbert | Fort Delaware, New Castle County, Delaware | 3 | M1896 carriages | 1901 | 1940 | guns sent to Puerto Rico | |

| Battery Pensacola | Fort Pickens, Florida | 2 | M1897 carriages | 1898 | 1934 | ||

| Battery Kirby | Fort Baker, California | 2 | M1897 carriages | 1900 | 1941 | shipped to Battery Cheney, Fort Mills, Corregidor | |

| Battery Duportail | Fort Morgan (Alabama) | 2 | 1900 | 1923 | |||

| Battery Lancaster | Fort Winfield Scott, California | 2 | M1897 carriages | 1901 | 1918 | ||

| Battery Chester | Fort Miley, California | 2 | M1897 carriages | 1902 | one gun removed in 1918 and the other in 1943 | ||

| Battery DeRussy | Fort Monroe, Virginia | 3 | M1901 carriages | 1904 | 1944 | ||

| Battery Parrott | Fort Monroe, Virginia | 2 | M1900 | M1901 carriages | 1928 | 1943 | two M1895 12-inch guns replaced two M1900 12-inch guns (installed 1906, rebuilt as AMTB 90mm battery)[15] |

| Battery Kingman | Fort Hancock, New Jersey | 1 | M1895MI | M1917 carriage | |||

| Battery Mahan | Fort Totten, New York | 2 | M1897 carriages | 1900 | 1918 | ||

| Battery Wilhelm | Fort Flagler, Washington | 2 | M1888MII | M1894 altered lift carriages | 1897 | 1942 | Two of three M1894 altered lift carriages produced, and received third from Battery Ash at Fort Worden, removed in 1909.[16] |

| Battery Ash | Fort Worden, Washington | 2 | M1888MII | M1892 barbette carriages | 1898 | 1942 | Emplacement 2 originally installed on M1894 altered lift carriage—dismantled and parts sent to Fort Flagler, 1909 [16][17] |

| Battery Kinzie | Fort Worden, Washington | 2 | M1895MI | M1901 disappearing carriages | 1908 | 1944 | |

| Battery Ayres | Fort Wadsworth, Richmond County, New York | 2 | M1897 carriages | 1902 | 1942 | ||

| Battery Hudson | Fort Wadsworth, Richmond County, New York | 1 | M1896 carriage | 1909 | 1918 | ||

| Battery Butterfield | Fort H.G. Wright, Fishers Island, Suffolk County, New York | 2 | M1897 carriages | 1900 | 1944 | ||

| Battery Crockett | Fort Mills, Corregidor, Philippine Islands | 2 | M1901 carriages | 1911 | captured by the Japanese 1942; recaptured 1945) | ||

| Battery Cheney | Fort Mills, Corregidor, Philippine Islands | 2 | M1901 carriages | 1910 | captured by the Japanese 1942; recaptured 1945 | ||

| Battery Wheeler | Fort Mills, Corregidor, Philippine Islands | 2 | M1901 carriages | 1909 | captured by the Japanese 1942; recaptured 1945 | ||

| Battery Hearn | Fort Mills, Corregidor, Philippine Islands | 1 | M1895MII | M1917 carriage | 1921 | captured by the Japanese 1942; recaptured 1945 | |

| Battery Smith | Fort Mills, Corregidor, Philippine Islands | 1 | M1895MII | M1917 carriage | 1921 | captured by the Japanese 1942; recaptured 1945 | |

| BCN 519 | Fort Miles, Delaware | 2 | M1895MII | 1943 | abandoned 1958 |

Additional batteries, including 14 two-gun batteries with long-range M1917 carriages (in addition to Batteries Smith and Hearn on Corregidor), were located in the United States and its possessions.[18][19][13]

Specifications

editVariations

edit- M1888 rifle 12" 440" 117,127 lb

- M1888MI rifle 12" 440" 117,127 lb

- M1888MII rifle 12" 440" 117,127 lb

- M1895 rifle 12" 442.56" 115,000 lb

- M1895MI rifle 12" 442.56" 115,000 lb

- M1900 rifle 12" 480" 132,380 lb

The M1895MI weighed 52 tons and the M1901 carriage weighed 251 tons. The projectile weight for all M1895 guns was 1,046 pounds. Each shell used 318 pounds of powder, but this was varied depending on range. The projectile achieved a muzzle velocity of 2,250 feet per second. The M1901 disappearing carriage could elevate 15 degrees maximum; earlier models could not elevate that much until the rear mounting bracket was changed from a centerline to an upper position in the M1901. The M1901 could traverse 170 degrees, but some M1895MII emplacements could traverse 210 degrees. The M1895MII had a range of over 29,000 yards (26 kilometers).[20]

Surviving examples

editNo M1888 or M1900 weapons survive.[21]

- One 12-inch gun M1895MIA4 (#1 Watervliet) on Barbette Carriage M1917 (#31 Eng. Machine), Battery Smith, Fort Mills, Corregidor Island, Philippines

- One 12-inch gun M1895MIA4 (#6 Watervliet) on Barbette Carriage M1917 (#30 Eng. Machine), Battery Hearn, Fort Mills, Corregidor Island, Philippines

- One 12-inch gun M1895MIA4 (#8 Watervliet) (spare gun), Battery Hearn, Fort Mills, Corregidor Island, Philippines

- Two 12-inch guns M1895 (#13 Bethlehem & #27 Watervliet) on disappearing carriages M1901 (#14 and #15 Watertown), Battery Crockett, Fort Mills, Corregidor Island, Philippines

- One 12-inch gun M1895 (#8 Bethlehem) (spare gun), Battery Crockett, Fort Mills, Corregidor Island, Philippines

- Two 12-inch guns M1895 (#37 & #12 Watervliet) on disappearing carriages M1901 (#16 and #17 Watertown), Battery Cheney, Fort Mills, Corregidor Island, Philippines

- One 12-inch gun M1895 (#16 Watervliet) (may be spare gun for Battery Cheney), Bottomside Area, Fort Mills, Corregidor Island, Philippines

- One 12-inch gun M1895 (#36 Watervliet) (remains of disappearing carriage in front of the parapet), Battery Wheeler, Fort Mills, Corregidor Island, Philippines

- One 12-inch gun M1895 (#7 Bethlehem) on disappearing carriage M1901 (#2 Watertown), Battery Wheeler, Fort Mills, Corregidor Island, Philippines

- One 12-inch gun M1895 (#10 Bethlehem) (spare gun), Battery Wheeler, Fort Mills, Corregidor Island, Philippines

- One 12-inch gun M1895MIA1 (#19) on railway mount M1918 (#9 Marion steam shovel), U.S. Army Ordnance School, Fort Gregg-Adams, VA.

- One 12-inch gun M1895 at Fort Miles, Lewes, Delaware[22]

See also

edit- Seacoast defense in the United States

- United States Army Coast Artillery Corps

- Coast Artillery fire control system

Weapons of comparable role, performance and era

edit- 12"/35 caliber gun - contemporary US Navy weapon

- BL 12-inch Mk VIII naval gun - contemporary British naval weapon

- Canon de 305 mm Modèle 1893/96 gun - contemporary French naval and railway weapon

References

edit- ^ a b c Berhow, p. 61

- ^ Berhow, pp. 130–155

- ^ Description of 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16-inch Seacoast Guns, p. 32

- ^ FM 4-80 Seacoast Artillery: Service of the Piece – 12-Inch and 14-Inch Guns (Disappearing Carriage)

- ^ Berhow, Mark A. and McGovern, Terrance C., American Defenses of Corregidor and Manila Bay 1898–1945, Osprey Publishing Ltd.; 1st edition, 2003; pages 7–8.

- ^ America's Munitions 1917-1918, pp. 96–98

- ^ a b Hogg, Ian V. (1998). Allied Artillery of World War I. Ramsbury, Wiltshire, UK: The Crowood Press, Ltd. pp. 141–142. ISBN 1-86126-104-7.

- ^ Miller, H. W., LTC, USA Railway Artillery, Vols. I and II, 1921, Vol. I, pp. 197–250[clarification needed]

- ^ Handbook of Ordnance Data, 15 November 1918, pp. 97–108

- ^ US Army Railway Artillery in World War I

- ^ Instructions for mounting, using and caring for Barbette carriage, model of 1917 for 12-inch gun, model of 1895 MI (1917)

- ^ Coast Defense Study Group fort and battery list

- ^ a b Berhow, pp. 224–226

- ^ Williford, pp. 80-83

- ^ FortWiki on Battery Parrott, Ft. Monroe

- ^ a b Berhow, Mark A. (1999). American Seacoast Defenses: A Reference Guide. Bel Air, Maryland: Coast Defense Study Group Press. p. 228.

- ^ "Battery Ash - FortWiki Historic U.S. and Canadian Forts". fortwiki.com. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ Search on FortWiki for M1895 12-inch gun

- ^ Berhow, pp. 200–223

- ^ Berhow, Mark A. and McGovern, Terrance C. American Defenses of Corregidor and Manila Bay 1898–1945, Osprey Publishing Ltd.; 1st edition, 2003; page 59.

- ^ Berhow, pp. 229-230

- ^ Gun is located at 38°46′34″N 75°05′14″W / 38.7761°N 75.0872°W

Bibliography

edit- Berhow, Mark A., ed. (2004). American Seacoast Defenses, A Reference Guide (Second ed.). CDSG Press. ISBN 0-9748167-0-1.

- Lewis, Emanuel Raymond (1979). Seacoast Fortifications of the United States. Annapolis: Leeward Publications. ISBN 978-0-929521-11-4.

- Miller, H. W. (1921). Railway Artillery. Vol. I and II. Washington: US Government Printing Office. pp. 197–250.[clarification needed]

- Williford, Glen M. (2016). American Breechloading Mobile Artillery, 1875-1953. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7643-5049-8.

External links

edit