Hideaki Sorachi (空知 英秋, Sorachi Hideaki, born May 25, 1979)[1] is the pen name[2] of a Japanese manga artist, most well known for his manga Gintama, which began serialization in 2003 and ended in 2019.[3] He has also written numerous one-shots, including Dandelion, for which he won the Tenkaichi Honourable Mention Manga Award in 2002.[4] Sorachi's distinctive sense of humour and writing style has been the subject of academic research papers.[5][6][7] As of February 2018, the Gintama manga has sold 55 million units in Japan.[8]

Sorachi Hideaki | |

|---|---|

| Born | May 25, 1979 |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Occupation | Manga artist |

| Years active | 2002–present |

| Notable work | Gintama |

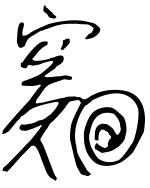

| Signature | |

| |

Personal life

editHideaki Sorachi was born on May 25, 1979, in Takikawa of Hokkaido, Japan. Sorachi has stated that his pen name is derived from the Sorachi prefecture in Hokkaido, but Hideaki is a part of his real name.[9] He has an older sister, and occasionally shares stories about her in the end notes of manga volumes.[2]

Sorachi has commented that he prefers using analog writing implements as opposed to creating digital art; his most used writing utensil being the calligraphy brush pen. He also uses felt-tip and permanent markers, and a round-nib and G-pen.[9][10][11]

In an interview, Sorachi described how watching Castle in the Sky in his childhood inspired him to start drawing manga, and how he feels like he “is always chasing after a castle in the sky”.[9] From a young age, he read various manga series, and he drew manga during breaks in elementary school. However, after his father ridiculed a manga he drew in 4th grade, Sorachi decided to give up on his dream of becoming a manga artist.[9][12]

Sorachi entered a university in Hokkaido, studying a degree in advertising. He recounted feeling unsure of his career path while enrolled at university, considering following his interests in both architecture and creating computer graphics. After graduating, Sorachi considered himself to be a "NEET", and sent his first work, Dandelion, to a publisher whilst being unsure of its potential success.[12]

Sorachi has stated that he does not use social media, including Twitter, as he “intend[s] to eliminate stress through manga”.[13]

Career

editSorachi, unemployed after graduating university, was able to live off Dandelion. Soon afterwards, he began writing the storyline for Gintama.[12]

At the start of the serialisation of Gintama, the series lacked popularity and support, leading to a potential cancellation.[12] While the first edition of the physical tankōbon volumes completely sold out, Shueisha had only printed the minimum number of volumes and still considered the sales to be “poor”. Sorachi believed that the manga was unlikely to become popular, and recounted other people also telling him that the manga would not surpass the printing of two tankōbon volumes.[14] However, interest in the manga slowly increased, to the extent that Sorachi found he did not have “any fresh material to use” after the release of the third volume.[15] He later stated that he was overjoyed when the manga was adapted into an anime, and, until then, hadn't fully grasped the extent to which the series was popular. Gintama was featured in the 2005 Jump Festa Anime Tour, which Sorachi visited and recounted seeing “the crowd’s reaction and realised that people actually knew about Gintama.”[16]

Writing style and influences

editResearchers have credited the popularity of the Gintama series to Sorachi's uniquely humorous characters and satirisation of contemporary themes.[5][6][7] It has been described by Sorachi as “Gently painting the life of a loser, a really likeable kind of humanity and reality”, stating that the appeal of the manga's characters are due to their relatable, flawed nature.[9] Smith has described the series as an “Edo-era comedy decked out in science fiction trappings and alternative historical versions of famous characters”.[7]

Critics have also complimented Sorachi's distinctive sense of humour, often satirising Japanese pop culture, or frequent use of vulgar language and toilet humour. Smith has considered Gintama’s balance of comedic elements and drama as representing Sorachi’s unique style and approach to characters.[5][6][7]

Sorachi stated that reading Wanpakku Comics had the greatest influence on his work as a manga artist, though was also inspired by popular series such as Akira Toriyama's Dragon Ball and Shigeru Mizuki's GeGeGe no Kitarou. He also mentioned that watching various variety shows and historical films served as creative inspiration for Gintama. Sorachi has stated that the midnight radio program Attack Young, by Akashi Eiichirou, inspired his satirical humour.[12][9]

In the early stages of production for Gintama, Sorachi stated that his editor encouraged him to write a story about the Japanese shinsengumi, due to the popularity of a TV drama called Shinsengumi! that was airing at the time. However, he felt that his creativity would be limited by the genre of historical fiction and thus decided to incorporate the shinsengumi as side characters in a science-fiction and comedy manga.[5][7]

The first year of the release of Gintama coincided with the airing of Shinsengumi!, during which the manga consisted mostly of shorter stories to establish the characters and the world they were situated in, as Sorachi wanted to minimise the potential overlap of the two texts. However, following the first year of serialisation, Sorachi stated that he grew more comfortable with extending the storyline of the manga to include more serious themes and dramatic moments, whilst keeping his uniquely comedic and fantastical characterisation of modern Japan.[11]

Sorachi's inspiration for the initial characterisation of the shinsengumi in Gintama was Ryotaro Shiba’s Moeyo Ken.[6][7][9] This characterisation was then further developed and adapted through the audience reception of Gintama, by mail, weekly surveys, and sales data.[5]

The character Hijikata Tōshirō in Gintama is considered to be Sorachi’s rendition of the popular protagonist Hijikata Toshizō in Moeyo Ken. Critics consider Tōshirō’s character to be the “embodiment of [Shinsengumi] values and virtues” within the manga, and is a major supporting character.[5] Sorachi stated that he initially wanted to make Hijikata the main character, but instead decided to create Gintoki Sakata as a “strong main character . . . who’s not part of an organisation” to make the series more memorable.[12]

In an interview with QuickJapan, Sorachi details the romantic appeal of the shinsengumi as characters and in Japanese pop culture:

“As for historical periods that see great changes, like Bakumatsu or Sengoku, you witness humanity under extreme conditions, and it brings out the good and the bad of humanity. I like that.”[12]

Sorachi's characterisation of women has been considered by academic reviewers as a subversion of stereotypical female archetypes in fiction, particularly through the rejection of conventional behaviours of women in manga.[5] He mentioned that he dislikes the trope of typical mangas with “unnaturally” cute female leads, and therefore created the character of Kagura in Gintama with the intention of portraying a “female lead who could throw up but still make people think she’s adorable”. However, Sorachi later realised that such characters were also unrealistic, though considered her character as a creative “challenge”.[12]

Appearances on Gintama

editSorachi has appeared on Gintama, both the manga and the anime, in a short comedy segment, often on the subject of writing and working as a manga artist. His character is drawn as a humanoid gorilla wearing a yellow shirt with the Japanese kanji 俺 (I, me). Sorachi voices this character himself in the Japanese Gintama anime.[17][18] Sorachi has also appeared in a life-sized suit of this character for promotional interviews on Gintama movie releases. In these appearances, a cast member will read out a letter written by Sorachi, about the stages of production or effort which went into creating the movie, frequented by sudden, comical one-liners.[19]

Crossovers and appearances

editKenta Shinohara (author of Sket Dance) used to be his assistant,[20] as well as Yōichi Amano (author of Akaboshi: Ibun Suikoden). Gintama and Sket Dance had a crossover chapter in Weekly Shōnen Jump, marking the 360th chapter for Gintama and the 180th for Sket Dance. The author for One Piece, Eiichiro Oda, also drew the main characters Gintoki Sakata from Gintama and Monkey D. Luffy from One Piece for the Gintama exhibition, and gave commentary on the series.[21]

Several other Weekly Shōnen Jump series have been referenced or parodied in Gintama, including One Piece, Naruto, and Dragon Ball.[22] The second season of the anime adaptation of Shūichi Asō's The Disastrous Life of Saiki K also featured a crossover with Gintama.[23]

During the premiere of the film Gintama: The Very Final, Sorachi hand drew physical cards of Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba characters, including the protagonist Tanjiro, which were then offered to those attending the film's release.[24] Sorachi wrote that the cards were acknowledging the success of the movie Demon Slayer -Kimetsu no Yaiba- The Movie: Mugen Train.[25]

Works

edit- Dandelion — one shot, 2002 (featured in volume 1 of Gintama)

- Shirokuro — one shot, 2003 (featured in volume 2 of Gintama)

- 13 — one shot, 2008 (featured in volume 24 of Gintama)

- Bankara — one shot, 2010 (featured in volume 38 of Gintama)

- Gintama — manga series, 2003–2019

- 3rd Year Z Class: GinPachi Sensei — light novels, 2006 – 2013 (illustrator)

Awards

editHideaki Sorachi received an honourable mention for the 71st Tenkaichi Manga award for his debut work, Dandelion. The Tenkaichi Manga Award was held from August 1996 to March 2003, replacing the Hop ☆ Step Award as a monthly newcomer award for Shōnen Jump, held by Shueisha.[4] Sorachi later described, in an interview, that winning the award aided his career as a manga artist.[12]

References

edit- ^ Sorachi, Hideaki (2009). Gin Tama, Vol. 10. Viz Media. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-4215-1623-3.

- ^ a b "Character Book 1 Interview". Yorozuya Soul. Archived from the original on May 27, 2015. Retrieved Sep 23, 2020.

- ^ 2004年新年2号 (in Japanese). Shueisha. Archived from the original on February 5, 2008. Retrieved June 18, 2009.

- ^ a b Shōnen Jump. (2002). Weekly Shōnen Jump. Shueisha, 42.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lee, R. (2011). Romanticising Shinsengumi in Contemporary Japan. New Voices (Sydney, N.S.W.), 4, 68–187. doi:10.21159/nv.04.08

- ^ a b c d Jones, H. (2013). Manga Girls: Sex, Love, Comedy and Crime in Recent Boys’ Anime and Manga. In B. Steger & A. Koch (Eds.), Manga Girl Seeks Herbivore Boy: Studying Japanese Gender at Cambridge (pp. 23-82). Lit Verlag.

- ^ a b c d e f Smith, A. (2020). What Do Manga Depict? Understanding Contemporary Japanese Comics and the Culture of Japan. (27834637) [Doctoral thesis, Indiana University of Pennsylvania]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- ^ Valdez, N. (2018). ‘Gintama’ Manga Hits New Sales Record. Comicbook. https://comicbook.com/anime/news/gintama-manga-sales-record-55-million/

- ^ a b c d e f g Sorachi, H. (2006). Gintama Official Character Book – Gin Channel!. Shueisha.

- ^ Jump Comics Channel. (2021, 8 January). Hideaki Sorachi draws! “Gintoki Sakata”. [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HGnLsfJMH6g

- ^ a b Sorachi, H (2008). Gin Tama, Vol.6 (p. 26). Viz Media.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Quick Japan (in Japanese). Otashuppan. October 2009. pp. 22–41. ISBN 978-4778311940.

- ^ Sorachi, H. (2013). Gin Tama, Vol. 50. Shueisha.

- ^ Sorachi, H. (2009). 銀魂公式キャラクターブック2 「銀魂五年生. [in Japanese] (pp. 194 - 195) Shueisha. ISBN 978-4-08-874805-4.

- ^ Sorachi, H. (2008). Gin Tama, Vol. 3 (pg. 2). Viz Media. ISBN 978-1-4215-1360-7.

- ^ Sorachi, H. (2010). Gin Tama, Vol. 19. Viz Media. ISBN 978-1-4215-2817-5.

- ^ Takamatsu, Shinji (director) (27 September 2007). "Don't complain about your job at home, do it somewhere else". Gin Tama. Season 2. Episode 75. TV Tokyo.

- ^ 映画『銀魂2』公式 [@gintama_film]. (20 June 2019) 連載を終えた #空知先生 がチーズ蒸しパンにならないことを願っています。15年間お疲れ様でした。この素晴らしい作品に出会わせてくれて、そして実写化まで許可してくださって、本当に本当にありがとうございました!!! [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/gintama_film/status/1141532636420067329?s=21

- ^ Warner Bros Channel. (2020, 24 January). Movie: Gintama The Final, Our Stage. JumpFesta2020. [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t3Qli44gpsk

- ^ Tan, Kevin (24 February 2008). "Samurai sci-fi". The Star. Archived from the original on 22 June 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- ^ Green, Scott (December 24, 2016). ""One Piece" And "Gintama" Authors Measure Up In Exhibit Comments". Crunchyroll. Retrieved September 18, 2021.

- ^ Ahmad, Suzail (2021-10-22). "10 Best Times Gintama Referenced Other Anime". gamerant.com.

- ^ Valdez, N. (2017). ‘Saiki K’ Anime Teases Upcoming ‘Gintama’ Crossover. Comicbook. https://comicbook.com/anime/news/saiki-k-gintama-crossover-anime/

- ^ Warner Bros Japan. (2021). 原作者・空知英秋先生が描いた「(たぶん?)最後の<万事屋>イラスト」が、第四週目の入場者プレゼントになることが決定!!<炭治郎&柱イラストカード>集合ビジュアルも解禁‼ [in Japanese] https://wwws.warnerbros.co.jp/gintamamovie/news/?id=38

- ^ Valdez, N. (2020). Gintama Creator Offering Demon Slayer Art for Fans Watching the Final Movie. Comicbook. https://comicbook.com/anime/news/gintama-creatir-demon-slayer-movie-art/

External links

edit- Hideaki Sorachi at Anime News Network's encyclopedia