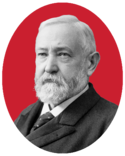

The 1892 Republican National Convention was held at the Industrial Exposition Building, Minneapolis, Minnesota, from June 7 to June 10, 1892. The party nominated President Benjamin Harrison for re-election on the first ballot and Whitelaw Reid of New York for vice president.[1]

| 1892 presidential election | |

Nominees Harrison and Reid | |

| Convention | |

|---|---|

| Date(s) | June 7–10, 1892 |

| City | Minneapolis, Minnesota |

| Venue | Industrial Exposition Building |

| Chair | William McKinley |

| Candidates | |

| Presidential nominee | Benjamin Harrison of Indiana |

| Vice-presidential nominee | Whitelaw Reid of New York |

| Other candidates | James G. Blaine William McKinley |

| Voting | |

| Total delegates | 906 |

| Votes needed for nomination | 454 |

| Results (president) | Harrison (IN): 535.17 (59.07%) McKinley (OH): 182 (20.09%) Blaine (ME): 181.83 (20.07%) Reed (ME): 4 (0.44%) Lincoln (IL): 1 (0.11%) |

| Ballots | 1 |

James S. Clarkson of Iowa was the outgoing chairman of the Republican National Committee. J. Sloat Fassett of New York was the temporary chairman, and Governor William McKinley of Ohio was the permanent chair of the convention.

James G. Blaine, Harrison's Secretary of State who had resigned from the cabinet on June 4, 1892, had his name submitted for consideration by the delegates on the eve of the convention but drew little support. Governor McKinley barely edged out Blaine for second place among the delegates.

Although successful in his bid for re-nomination, President Harrison's performance was underwhelming for an incumbent, due in part to the crushing defeat that the party had suffered in the 1890 midterm elections. He and Reid would lose the 1892 general election to former president Grover Cleveland and his running mate Adlai Stevenson.

The 1892 RNC was also the first convention where women were allowed to be delegates. Therese Alberta (Parkinson) Jenkins, delegate from Wyoming, cast the first vote by a woman for president; Wyoming had granted full suffrage for women at statehood in 1890.

Preconvention

editBenjamin Harrison lost the support of Mark Hanna and Thomas Brackett Reed due to his patronage decisions. Hanna was the treasurer of the Republican National Committee and raised significant funds for Harrison in 1888. Matthew Quay gave his support to the anti-Harrison movement as he felt Harrison accepted his resignation as chair of the RNC too quickly. Thomas C. Platt was critical of Harrison for not making him Secretary of the Treasury.[2]

Quay, James S. Clarkson, and other Republicans attempted to have James G. Blaine run, but Blaine announced that he would not on February 1, 1892. Anti-Harrison Republicans considered supporting Russell A. Alger, Shelby M. Cullom, William McKinley, Reed, Whitelaw Reid, and John Sherman.[3]

Henry W. Blair, a former U.S. senator from New Hampshire, declared his candidacy in February 1892.[4][5] Quay supported McKinley at the convention.[6]

Michigan, Minnesota, and Ohio sent uninstructed delegations.[7]

Convention

editOn November 22, 1891, the RNC voted on the seventh ballot to have Minneapolis host the convention. Cincinnati, New York City, Omaha, and San Francisco also made bids to host it.[8]

Many of Blaine's old supporters encouraged him to run for the nomination.[9] Blaine had denied any interest in the nomination months before his resignation, but some of his friends, including Quay and Clarkson took it for false modesty and worked for his nomination anyway.[10] Blaine resigned as Secretary of State on June 4, three days before the convention. This led to many Republicans believing that he would seek the nomination. Blaine's sister-in-law Mary Abigail Dodge wrote in her biography of him that his resignation was not due to an interest in the nomination.[11]

Harrison wanted McKinley to place his name up for nomination, but McKinley declined to answer if he would. Louis T. Michener asked McKinley at the convention if he would support Harrison, but he declined to answer. Hanna, who was a delegate to the convention, opened an unofficial headquarters for McKinley at a nearby hotel and committed the Ohio delegation for him. Harrison's allies arranged for McKinley to become chair of the convention where he would be forced to play a neutral role. Quay praised this plan stating that it would make "it impossible for McKinley to Garfield the convention".[12]

Blaine was nominated by Colorado delegate Edward O. Wolcott, Harrison by Indiana delegate Richard W. Thompson. Warner Miller seconded Blaine's nomination and Chauncey Depew seconded Harrison's nomination. McKinley attempted to have the convention nominate Harrison by acclamation, but withdrew his proposal due to opposition. Harrison won the nomination on the first ballot. The convention later voted to make his nomination unanimous.[13] McKinley objected to delegate votes being cast for him.[14]

On July 27, Clarkson, who opposed Harrison's renomination, was replaced as chair of the RNC by William James Campbell. Campbell resigned on July 6, and Thomas H. Carter was selected to replace him on July 16.[15]

| Presidential Ballot[16] | |

|---|---|

| Candidate | 1st |

| Harrison | 535.17 |

| Blaine | 182.5 |

| McKinley | 182 |

| Reed | 4 |

| Lincoln | 1 |

| Not Voting | 2 |

Vice presidential nomination

editNo Republican vice president was renominated for a second term at the time of the convention. Vice President Levi P. Morton did not campaign for renomination.[17] Morton was dumped from the ticket, as Harrison was not particularly fond of Morton, who was closer to Blaine supporters; Morton himself was not interested in serving another term as vice president in any event, having been persuaded by his confidantes to run for governor of New York at the next scheduled election in 1894.[18]

Reid was nominated by Edmund O'Connor and seconded by Horace Porter. Reed was nominated by Josiah T. Settle and seconded by C.M. Louthan. However, Maine's delegation stated that Reed was not interested in the nomination. Reid won the nomination with a unanimous vote.[17]

Platform

editThis section contains too many or overly lengthy quotations. (November 2013) |

The Republican platform supported high tariffs, bimetallism, stiffer immigration laws, free rural mail delivery, and a canal across Central America. It also expressed sympathy for the Irish Home Rule Movement and the plight of Jews under persecution in czarist Russia.[19]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Different twin city, but a similar RNC tale 116 years later". Twin Cities. 2008-08-10. Retrieved 2018-05-29.

- ^ Knoles 1971, p. 35-36.

- ^ Knoles 1971, p. 37-40.

- ^ Knoles 1971, p. 40.

- ^ "Blair a Presidential Candidate". Fremont Daily Herald. February 23, 1892. p. 2. Archived from the original on February 9, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Knoles 1971, p. 42.

- ^ Knoles 1971, p. 43.

- ^ Knoles 1971, p. 49.

- ^ Calhoun, pp. 134–139; Muzzey, pp. 468–469.

- ^ Muzzey, pp. 469–472.

- ^ Knoles 1971, p. 52-53.

- ^ Knoles 1971, p. 58-61.

- ^ Knoles 1971, p. 66-68.

- ^ Horner, pp. 92–96.

- ^ Knoles 1971, p. 122-124.

- ^ Knoles 1971, p. 68.

- ^ a b Knoles 1971, p. 71.

- ^ "Levi Parsons Morton, 22nd Vice President (1889-1893)". US Senate. US Senate. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ^ History of American Presidential Elections Volume II 1848-1896; Schlesinger; Pgs 1739-1741

Works cited

edit- Knoles, George (1971). The Presidential Campaign and Election of 1892. Stanford University Press. ISBN 040450969X.

Bibliography

edit- Calhoun, Charles William (2005). Benjamin Harrison. New York: Times Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-6952-5.

- Horner, William T. (2010). Ohio's Kingmaker: Mark Hanna, Man and Myth. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-8214-1894-9.

- Huber, Molly (April 26, 2011). "Republican National Convention, June 1892". MNopedia. Minnesota Historical Society. Retrieved November 3, 2012.

- Muzzey, David Saville (1934). James G. Blaine: A Political Idol of Other Days. New York: Dodd, Mead, and Company.

External links

edit- Republican Party platform of 1892 at The American Presidency Project

- Harrison acceptance letter at The American Presidency Project

| Preceded by 1888 Chicago, Illinois |

Republican National Conventions | Succeeded by 1896 St. Louis, Missouri |