The Persian Tobacco Protest (Persian: نهضت تنباکو, romanized: nehzat-e tanbāku) was a Twelver Shia Muslim revolt in Qajar Iran against an 1890 tobacco concession granted by Emperor Naser al-Din Shah Qajar to the British Empire, granting control over growth, sale, and export of tobacco to an Englishman, Major G. F. Talbot. The protest was held by merchants in major cities such as Tehran, Shiraz, Mashhad, and Isfahan in solidarity with the clerical establishment. It climaxed in a widely obeyed December 1891 fatwa against tobacco use issued by Grand Ayatollah Mirza Shirazi.

Background

editBeginning in the 19th century, Qajar Iran found itself in a precarious situation due to an increasing foreign presence. Reeling from defeats in wars against the Russian Empire in 1813 and 1828, as well as the British Empire in 1857, not only was the Qajar government forced to grant countless concessions to foreign powers, but Iranian bazaaris (merchants) were left in a highly vulnerable position as they were unable to compete with the numerous economic advantages gained by merchants from Europe.[1] According to the accounts of foreigners living in Iran at the time, the Qajar dynasty was highly unpopular among the populace and was perceived as having little concern for the welfare of its subjects. Later accounts by British eyewitnesses suggest that the reason why the dynasty had not been overthrown sooner in the face of widespread discontent was due to British and Russian intervention that essentially propped up the emperor.[2]

In 1872, Emperor Naser al-Din negotiated a concession with Paul Reuter, a British citizen, granting him control over the roads, telegraphs, mills, factories, extraction of resources, and other public works in exchange for a stipulated sum for five years and 60% of all the net revenue for 20 years. The Reuter concession was met with not only domestic outrage in the form of local protests, but also opposition from the Russian government.[3] Under immense pressure, Naser al-Din Shah consequently canceled the agreement despite his deteriorating financial situation. While the concession lasted for approximately a year, the debacle set the foundation for the revolts against the tobacco concession in 1890 as it demonstrated that any attempt by a foreign power to infringe upon Iranian sovereignty would infuriate the local population as well as rival European powers.[4]

The Tobacco Régie and subsequent protests

editOn 20 March 1890, Emperor Naser al-Din granted a concession to Major G. F. Talbot for a full monopoly over the production, sale, and export of tobacco for fifty years. In exchange, Talbot paid the emperor an annual sum of £15,000 (present-day £1.845 million; $2.35 million) in addition to a quarter of the yearly profits after the payment of all expenses and a dividend of five percent on the capital. By the fall of 1890, the concession had been sold to the Imperial Tobacco Corporation of Persia, a company which some have speculated was essentially Talbot himself as he heavily promoted shares in the corporation.[5] At the time of the concession, the tobacco crop was valuable not only because of the domestic market but because Iranians cultivated a variety of tobacco "much prized in foreign markets" that was not grown elsewhere.[6] The Tobacco Régie (monopoly) was subsequently established and all the producers and owners of tobacco in the Qajar Empire were forced to sell their goods to agents of the Régie, who would then resell the purchased tobacco at a price that was mutually agreed upon by the company and the sellers with disputes settled by compulsory arbitration.[6]

At the time, the tobacco industry in Iran employed over 200,000 people and therefore the concession represented a major blow to farmers and bazaaris, whose livelihoods were largely dependent on the lucrative tobacco business.[7] Now they were forced to seek permits from the Tobacco Régie as well as required to inform the concessionaires of the amount of tobacco produced. In essence the concession not only violated the long-established relationship between Persian tobacco producers and tobacco sellers, but also threatened the job security of a significant portion of the population.[8]

In September 1890, the first resounding protest against the concession manifested, however it did not emerge from the Persian merchant class or ulama but rather from the Russian government who stated that the Tobacco Régie violated freedom of trade in the region as stipulated by the Treaty of Turkmanchai.[9] Despite disapproval from the Russian Empire, Naser al-Din Shah was intent on continuing the concession. In February 1891, Major G. F. Talbot traveled to Iran to install the Tobacco Régie, and soon thereafter, the Emperor made news of the concession public for the first time, sparking immediate disapproval throughout the country.

Despite the rising tensions, director of the Tobacco Régie Julius Ornstein arrived in Tehran in April and was assured by Prime Minister Amin al-Sultan that the concession had the full support of the House of Qajar.[10] In the meantime, anonymous letters were being sent to high members of the government while placards were circulating in cities such as Tehran and Tabriz, both displaying public anger towards the granting of concessions to foreigners.[11]

During the spring of 1891, mass protests against the Régie began to emerge in major Iranian cities. Initially, it was the bazaaris who led the opposition under the conviction that it was their income and livelihood which were at stake. Affluent merchants such as Hajji Mohammad Kazem Malek el-Tojjar, the "king of the merchants", played a vital role in the tobacco movement by organizing bazaari protests as well as appealing to well-known mujtahids for their support in opposing the Régie.[12]

The ulama proved to be a highly valuable ally of the bazaaris as key religious leaders sought to protect national interests from foreign domination. Since the Safavid conversion of Iran to Shia Islam after 1501, the ulama played a paramount role in society – they ran religious schools, maintained the charity of endowments, acted as arbiters and judges, and were seen as the intermediaries between God and Muslims in the country. If such exorbitant concessions were given to non-Muslim foreigners, the ulama believed the community under their supervision would be severely threatened.[13] Furthermore, the ulama had ties with various merchant families and guilds while holding an economic interest in tobacco that was grown on waqf land.[14] Finally, as the clergy pointed out, the concession directly contradicted sharia, because individuals were not allowed to purchase or sell tobacco of their own free will and were unable to go elsewhere for business. Later, during the tobacco harvest season of 1891, tobacco cultivator Mahmud Zaim of Kashan coordinated with two other major tobacco cultivators the burning of their entire stock.

The cities of Shiraz, Tabriz, and Tehran would subsequently develop into the most prominent centers of opposition to the tobacco concession. In May 1891, Sayyid Ali Akbar, a prominent mullah of Shiraz, was removed from the city by orders of the Emperor due to his preaching against the concession. During his departure, Ali Akbar met with prominent pan-Islamist activist Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, and at Akbar's request, al-Afghani wrote a letter to the leading cleric, Mirza Shirazi, asking the mujtahids to "save and defend [the] country" from "this criminal who has offered the provinces of the land of Iran to auction amongst the Great Powers."[15] Though Shirazi would later send a personal telegram to the shah warning the leader about the pitfalls of giving concessions to foreigners, this personal appeal did nothing to put an end to the Régie.

Government intervention may have helped in mitigating the hostilities in Shiraz following Akbar's removal, however other regions of Iran still saw a proliferation in protests. Bazaaris in Tehran were among the first groups of people to protest against the concession by writing letters of disapproval to the emperor even before the concession was publicly announced. It has been argued that this initial opposition stemmed from a Russian attempt to stir up frustration within the merchant community of Tehran.[7] Although Azarbaijan, the northwestern region, was not a tobacco-growing area, it saw tremendous opposition to the concession due to the large concentration of local merchants and retail traders in the region.[16] In Isfahan, a boycott of the consumption of tobacco was implemented even before Shirazi's fatwa, while in the city of Tabriz, the bazaar closed down and the ulama stopped teaching in the madrasas.[17] The cities of Mashhad and Kerman also experienced demonstrations in opposition to the concession, yet historian Mansoor Moaddel argues that these latter movements were relatively ineffective.[18] Other cities around the country such as Qazvin, Yazd, and Kermanshah were also involved in opposing the emperor and the Tobacco Régie.

Shirazi's fatwa and the repudiation of the concession

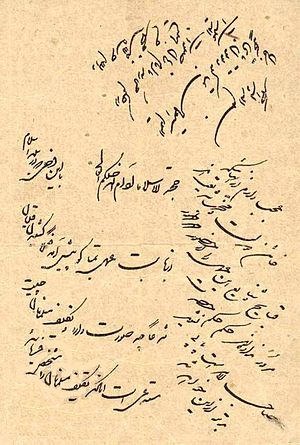

editIn December 1891, a fatwa was issued by the most important religious authority in Iran, the marja'-i taqlid Mirza Shirazi: "In the name of God, the Merciful, the Beneficent. Today the use of both varieties of tobacco, in whatever fashion is reckoned war against the Imam of the Age – may God hasten his advent."[19] The reference to the Hidden Imam, a critical person in Twelver Shi'ism, meant that Shirazi was using the strongest possible language to oppose the Régie.

Initially, there was skepticism over the legitimacy of the fatwa; however, Shirazi would later confirm the declaration.

Residents of the capital of Tehran refused to smoke tobacco and this collective response spread to neighboring provinces.[20] In a show of solidarity, Iranian merchants responded by shutting down the main bazaars throughout the country. As the tobacco boycott grew larger, Naser al-Din Shah and Prime Minister Amin al-Sultan found themselves powerless to stop the popular movement fearing Russian intervention in case a civil war materialized.[21]

Before the fatwa, tobacco consumption had been so prevalent in Iran that it was smoked everywhere, including inside mosques. European observers noted that "most Iranians would rather forego bread than tobacco, and the first thing they would do at the breaking of the fast during the month of Ramadan was to light their pipes."[22] Despite the popularity of tobacco, the religious ban was so successful that it was said that women in the Qajar harem quit smoking and his servants refused to prepare his water pipe.[23][incomplete short citation]

By January 1892, when the shah saw that the British government "was waffling in its support for the Imperial Tobacco Company," he canceled the concession.[24] On January 26, 1892, "the public crier in Tehran announced that Sheikh Shirazi had lifted the fatva."[19]

The fatwa has been called a "stunning" demonstration of the power of the marja'-i taqlid, and the protest itself has been cited as one of the issues that led to the Persian Constitutional Revolution a few years later.

Aftermath

editFollowing the cancellation of the concession, there were still difficulties between the Qajar government and the Imperial Tobacco Corporation of Persia in terms of negotiating the amount of compensation that would be paid to the company. Eventually, it was decided that the sum was to be £500,000[25] (equivalent to £69,000,000 in 2023 , corresponding to 72,000,000$ ). While many Iranians were happy about preventing foreign commercial influence in the country, the tobacco movement had far greater implications than they would even realize. Historian Nikki Keddie notes that the movement was significant because "Iranians saw for the first time that it was possible to win out against the Shah and foreign interests… there is a direct line from the coalition which participated in the tobacco movement… culminating in the Constitutional Revolution" and arguably the Iranian Revolution as well.[26]

For Naser Al-Din Shah, the protest left him both financially handicapped and publicly humiliated. Iran was forced to contract a loan from Russia and became a debtor state. At the end of his rule, Naser Al-Din became much more hostile towards the West, preventing any form of European education or travel.[27]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Moaddel 1992, p. 455.

- ^ Keddie 1966, p. 3.

- ^ Keddie 1966, p. 5.

- ^ Lambton 1987, p. 223.

- ^ Keddie 1966, p. 38.

- ^ a b Mottahedeh 2000, p. 215.

- ^ a b Moaddel 1992, p. 459.

- ^ Poulson, Stephen. Social Movements in Twentieth-Century Iran. Lexington, 2005, p. 86.

- ^ Keddie 1966, p. 43.

- ^ Lambton 1987, p. 229.

- ^ Keddie 1966, p. 55.

- ^ Poulson, p. 87.

- ^ Algar, Hamid. Religion and State in Iran 1785–1906. University of California, 1969, p. 208.

- ^ Keddie 1966, p. 65.

- ^ Mottahedeh 2000, pp. 216–217.

- ^ Moaddel 1992, p. 460.

- ^ Algar, p. 209.

- ^ Moaddel 1992, p. 463.

- ^ a b Mackey-1996-p.141

- ^ Lambton 1987, p. 247.

- ^ Lambton 1987, p. 248.

- ^ Gilman, Sander L.; Zhou, Xun (2004). Smoke: A Global History of Smoking. Reaktion Books. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-86189-200-3.

- ^ Nasr, p. 122.

- ^ Mottahedeh 2000, p. 218.

- ^ Keddie 1966, p. 125.

- ^ Keddie 1966, p. 131.

- ^ Cleveland, William L.; Bunton, Martin (2013). A history of the modern Middle East (Fifth ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview Press. pp. 106–107. ISBN 9780813348339.

Bibliography

edit- Moaddel, Mansoor (1992). Shi'i Political Discourse and Class Mobilization in the Tobacco Movement of 1890–1892. Vol. 7. Sociological Forum.

- Keddie, Nikki R. (1966). Religion and Rebellion in Iran: The Tobacco Protest of 1891–92. Frank Cass. ISBN 9780714619712.

- Lambton, Ann K. S. (1987). Qajar Persia. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292769007.

- Mackey, Sandra (1996). The Iranians : Persia, Islam and the Soul of a Nation by Sandra Mackey,. New York: Dutton.

- Mottahedeh, Roy P. (2000). The Mantle of the Prophet: Religion and Politics in Iran. Oneworld Publications. ISBN 9781851686162.