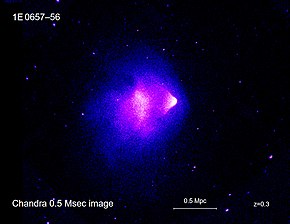

The Bullet Cluster (1E 0657-56) consists of two colliding clusters of galaxies. Strictly speaking, the name Bullet Cluster refers to the smaller subcluster, moving away from the larger one. It is at a comoving radial distance of 1.141 Gpc (3.72 billion light-years).[2]

| Bullet Cluster | |

|---|---|

X-ray photo by Chandra X-ray Observatory. Exposure time was 140 hours. The scale is shown in megaparsecs. Redshift (z) = 0.3, meaning its light has wavelengths stretched by a factor of 1.3. | |

| Observation data (Epoch J2000) | |

| Constellation(s) | Carina |

| Right ascension | 06h 58m 37.9s |

| Declination | −55° 57′ 0″ |

| Number of galaxies | ~40 |

| Redshift | 0.296[1] |

| Distance | 1.141 Gpc (3.7 billion light-years).[2] |

| ICM temperature | 17.4 ± 2.5 keV |

| X-ray luminosity | 1.4 ± 0.3 × 1039 h50−2 joule/s (bolometric)[1] |

| X-ray flux | 5.6 ± 0.6 × 10−19 watt/cm2 (0.1–2.4 keV)[1] |

| Other designations | |

| 1E 0657-56, 1E 0657-558 | |

The object is of a particular note for astrophysicists, because gravitational lensing studies of the Bullet Cluster are claimed to provide strong evidence for the existence of dark matter.[3][4] Observations of other galaxy cluster collisions, such as MACS J0025.4-1222, similarly support the existence of dark matter.[5]

Overview

editThe major components of the cluster pair—stars, gas and the putative dark matter—behave differently during collision, allowing them to be studied separately. The stars of the galaxies, observable in visible light, were not greatly affected by the collision, and most passed right through, gravitationally slowed but not otherwise altered. The hot gas of the two colliding components, seen in X-rays, represents most of the baryonic, or "ordinary", matter in the cluster pair. The gases of the intracluster medium interact electromagnetically, causing the gases of both clusters to slow much more than the stars.

The third component, the dark matter, was detected indirectly by the gravitational lensing of background objects. In theories without dark matter, such as modified Newtonian dynamics (MOND), the lensing would be expected to follow the baryonic matter; i.e. the X-ray gas. However, the lensing is strongest in two separated regions near (possibly coincident with) the visible galaxies. This provides support for the idea that most of the gravitation in the cluster pair is in the form of two regions of dark matter, which bypassed the gas regions during the collision. This accords with predictions of dark matter as only gravitationally interacting, other than weakly interacting.

The Bullet Cluster is one of the hottest-known clusters of galaxies. It provides an observable constraint for cosmological models, which may diverge at temperatures beyond their predicted critical cluster temperature.[1] Observed from Earth, the subcluster passed through the cluster center 150 million years ago, creating a "bow-shaped shock wave located near the right side of the cluster" formed as "70 million kelvin gas in the sub-cluster plowed through 100 million kelvin gas in the main cluster at a speed of about nearly 10 million km/h (6 million miles per hour)".[6][7][8] The bow shock radiation output is equivalent to the energy of 10 typical quasars.[1]

Significance to dark matter

editThe Bullet Cluster provides strong evidence for the nature of dark matter[4][9] and provides "evidence against some of the more popular versions of modified Newtonian dynamics (MOND)" as applied to large galactic clusters.[10] At a statistical significance of 8σ, it was found that the spatial offset of the center of the total mass from the center of the baryonic mass peaks cannot be explained with an alteration of the gravitational force law alone.[11]

According to Greg Madejski:

Particularly compelling results were inferred from the Chandra observations of the 'bullet cluster' (1E0657-56; Fig. 2) by Markevitch et al. (2004) and Clowe et al. (2004). Those authors report that the cluster is undergoing a high-velocity (around 4,500 km/s) merger, evident from the spatial distribution of the hot, X-ray-emitting gas, but this gas lags behind the subcluster galaxies. Furthermore, the dark matter clump, revealed by the weak lensing map, is coincident with the collisionless galaxies, but lies ahead of the collisional gas. This—and other similar observations—allow good limits on the cross-section of the self-interaction of dark matter.[12]

According to Eric Hayashi:

The velocity of the bullet subcluster is not exceptionally high for a cluster substructure, and can be accommodated within the currently favoured Lambda-CDM model cosmology."[13]

A 2010 study claimed that the velocities of the collision are "incompatible with the prediction of a LCDM model".[14] However, subsequent work has found the collision to be consistent with LCDM simulations,[15] with the previous discrepancy stemming from small simulations and the methodology of identifying pairs. Earlier work claiming the Bullet Cluster was inconsistent with standard cosmology was based on an erroneous estimate of the in-fall velocity based on the speed of the shock in the X-ray-emitting gas.[15] Based on the analysis of the shock driven by the merger, it was recently argued that a lower merger velocity ~3,950 km/s is consistent with the Sunyaev–Zeldovich effect and X-ray data, provided that the equilibration of the electron and ion downstream temperatures is not instantaneous.[16]

Alternative interpretations

editMordehai Milgrom, the original proposer of modified Newtonian dynamics, has posted an online rebuttal[17] of claims that the Bullet Cluster proves the existence of dark matter. He contends that the observed characteristics of the Bullet Cluster could just as well be caused by undetected standard matter.

Another study in 2006[18] cautions against "simple interpretations of the analysis of weak lensing in the bullet cluster", leaving it open that even in the non-symmetrical case of the Bullet Cluster, MOND, or rather its relativistic version TeVeS (tensor–vector–scalar gravity), could account for the observed gravitational lensing.

See also

edit- Galaxy group

- Galaxy cluster

- Abell 520 – a similar galaxy cluster whose dark and luminous matter may have been separated during a major collision

- NGC 1052-DF2

- List of galaxy groups and clusters

References

edit- ^ a b c d e Tucker, W.; Blanco, P.; Rappoport, S. (March 1998). "1E 0657-56: A Contender for the Hottest Known Cluster of Galaxies". Astrophysical Journal Letters. 496 (1). David, L.; Fabricant, D.; Falco, E. E.; Forman, W.; Dressler, A.; Ramella, M.: L5. arXiv:astro-ph/9801120. Bibcode:1998ApJ...496L...5T. doi:10.1086/311234. S2CID 16140198.

- ^ a b "NED results for object Bullet Cluster". NASA Extragalactic Database. Retrieved March 4, 2012.

- ^ Clowe, Douglas; Gonzalez, Anthony; Markevich, Maxim (2004). "Weak lensing mass reconstruction of the interacting cluster 1E0657-558: Direct evidence for the existence of dark matter". Astrophys. J. 604 (2): 596–603. arXiv:astro-ph/0312273. Bibcode:2004ApJ...604..596C. doi:10.1086/381970. S2CID 12184057.

- ^ a b M. Markevitch; A. H. Gonzalez; D. Clowe; A. Vikhlinin; L. David; W. Forman; C. Jones; S. Murray & W. Tucker (2004). "Direct constraints on the dark matter self-interaction cross-section from the merging galaxy cluster 1E0657-56". Astrophys. J. 606 (2): 819–824. arXiv:astro-ph/0309303. Bibcode:2004ApJ...606..819M. doi:10.1086/383178. S2CID 119334056.

- ^ Brada, M; Allen, S. W; Ebeling, H; Massey, R; Morris, R. G; von der Linden, A; Applegate, D (2008). "Revealing the Properties of Dark Matter in the Merging Cluster MACS J0025.4-1222". The Astrophysical Journal. 687 (2): 959. arXiv:0806.2320. Bibcode:2008ApJ...687..959B. doi:10.1086/591246. S2CID 14563896.

- ^ Chandra X-ray Observatory (2002). 1E 0657-56: A bow shock in a merging galaxy cluster (image and description). Chandra photo album. Harvard University.

- ^ 1e065756. spaceimages.com (photo).

- ^ "The dynamical status of the cluster of galaxies 1E0657-56". edpsciences-usa.org. 2002. Archived from the original on 2015-04-18. Retrieved 2007-09-02.

- ^ Markevitch, M.; Randall, S.; Clowe, D.; Gonzalez, A. & Bradac, M. (16–23 July 2006). Dark Matter and the Bullet Cluster (PDF). 36th COSPAR Scientific Assembly (abstract). Beijing, China.

- ^ Randall, Scott (31 May 2006). "Lunch-time talk" (abstract). Harvard University.

- ^ Clowe, Douglas; et al. (2006). "A Direct Empirical Proof of the Existence of Dark Matter". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 648 (2): L109–L113. arXiv:astro-ph/0608407. Bibcode:2006ApJ...648L.109C. doi:10.1086/508162. S2CID 2897407.[full citation needed]

- ^ Tucker, W.; Blanco, P.; Rappoport, S.; David, L.; Fabricant, D.; Falco, E.E.; Forman, W.; Dressler, A.; Ramella, M. (2006). "Recent and Future Observations in the X-ray and Gamma-ray Bands: Chandra, Suzaku, GLAST, and NuSTAR". AIP Conference Proceedings. 801: 21–30. arXiv:astro-ph/0512012. Bibcode:2005AIPC..801...21M. doi:10.1063/1.2141828. S2CID 14601312.

- ^ Hayashi, Eric; White, ? (2006). "How rare is the Bullet Cluster?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Letters. 370 (1): L38–L41. arXiv:astro-ph/0604443. Bibcode:2006MNRAS.370L..38H. doi:10.1111/j.1745-3933.2006.00184.x. S2CID 16684392.[full citation needed]

- ^ Lee, Jounghun; Komatsu, Eiichiro (2010). "Bullet Cluster: A Challenge to LCDM Cosmology". Astrophysical Journal. 718 (1): 60–65. arXiv:1003.0939. Bibcode:2010ApJ...718...60L. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/718/1/60. S2CID 119250064.

- ^ a b Thompson, Robert; Davé, Romeel; Nagamine, Kentaro (2015-09-01). "The rise and fall of a challenger: The Bullet Cluster in Lambda cold dark matter simulations". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 452 (3): 3030–3037. arXiv:1410.7438. Bibcode:2015MNRAS.452.3030T. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv1433. ISSN 0035-8711.

- ^ Di Mascolo, L.; Mroczkowski; Churazov, E.; Markevitch, M.; Basu, K.; Clarke, T.E.; et al. (2019). "An ALMA+ACA measurement of the shock in the Bullet Cluster". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 628: A100. arXiv:1907.07680. Bibcode:2019A&A...628A.100D. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201936184. S2CID 197545195.

- ^ Milgrom, Moti, "Milgrom's perspective on the Bullet Cluster", The MOND Pages, archived from the original on July 21, 2016, retrieved December 27, 2016

- ^ G.W. Angus; B. Famaey & H. Zhao (2006). "Can MOND take a bullet? Analytical comparisons of three versions of MOND beyond spherical symmetry". Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 371 (1): 138–146. arXiv:astro-ph/0606216. Bibcode:2006MNRAS.371..138A. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.10668.x. S2CID 15025801.

Further reading

edit- Clowe, Douglas; Bradač, Maruša; Gonzalez, Anthony H.; Markevitch, Maxim; Randall, Scott W.; Jones, Christine; Zaritsky, Dennis (2006). "A Direct Empirical Proof of the Existence of Dark Matter". The Astrophysical Journal. 648 (2): L109–L113. arXiv:astro-ph/0608407. Bibcode:2006ApJ...648L.109C. doi:10.1086/508162. S2CID 2897407.

- Bradač, Maruša; Clowe, Douglas; Gonzalez, Anthony H.; Marshall, Phil; Forman, William; Jones, Christine; Markevitch, Maxim; Randall, Scott; Schrabback, Tim; Zaritsky, Dennis (2006). "Strong and Weak Lensing United. III. Measuring the Mass Distribution of the Merging Galaxy Cluster 1ES 0657−558". The Astrophysical Journal. 652 (2): 937–947. arXiv:astro-ph/0608408. Bibcode:2006ApJ...652..937B. doi:10.1086/508601. S2CID 119388532.

- Angus, G. W.; Famaey, B.; Zhao, H. S. (2006). "Can MOND take a bullet? Analytical comparisons of three versions of MOND beyond spherical symmetry". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 371 (1): 138–146. arXiv:astro-ph/0606216. Bibcode:2006MNRAS.371..138A. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.10668.x. S2CID 15025801.

- Angus, Garry W.; Shan, HuanYuan; Zhao, HongSheng; Famaey, Benoit (2006). "On the Proof of Dark Matter, the Law of Gravity and the Mass of Neutrinos". The Astrophysical Journal. 654: L13–L16. arXiv:astro-ph/0609125. doi:10.1086/510738. S2CID 17977472.

- Brownstein, J. R.; Moffat, J. W. (2007). "The Bullet Cluster 1E0657-558 evidence shows modified gravity in the absence of dark matter". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 382 (1): 29–47. arXiv:astro-ph/0702146. Bibcode:2007MNRAS.382...29B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2007.12275.x. S2CID 119084968.

- CXO: Bedeviling Devil's Advocate Cosmology (The Chandra Chronicles) August 21, 2006

- CXO: 1E 0657-56: NASA Finds Direct Proof of Dark Matter Combined image of x-rays, visual and DM

- Harvard animation of the collision showing how the dark matter and normal matter become separated.

- Harvard Harvard Symposium: Markevitch PDF 36 color images and text slides modelling the existence of Dark Matter from Bullet cluster data

- NASA: NASA Finds Direct Proof of Dark Matter Archived 2017-06-25 at the Wayback Machine (NASA Press Release 06-096) Aug. 21, 2006

- Scientific American Scientific American article Science News August 22, 2006 Colliding Clusters Shed Light on Dark Matter that includes a movie of a simulation of the collision