The infinite series whose terms are the natural numbers 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + ⋯ is a divergent series. The nth partial sum of the series is the triangular number

which increases without bound as n goes to infinity. Because the sequence of partial sums fails to converge to a finite limit, the series does not have a sum.

Although the series seems at first sight not to have any meaningful value at all, it can be manipulated to yield a number of different mathematical results. For example, many summation methods are used in mathematics to assign numerical values even to a divergent series. In particular, the methods of zeta function regularization and Ramanujan summation assign the series a value of −+1/12, which is expressed by a famous formula:[2]

where the left-hand side has to be interpreted as being the value obtained by using one of the aforementioned summation methods and not as the sum of an infinite series in its usual meaning. These methods have applications in other fields such as complex analysis, quantum field theory, and string theory.[3]

In a monograph on moonshine theory, University of Alberta mathematician Terry Gannon calls this equation "one of the most remarkable formulae in science".[4]

Partial sums

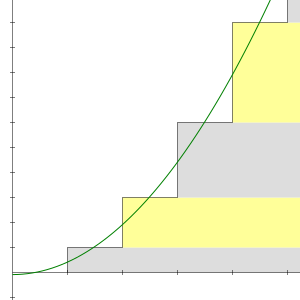

editThe partial sums of the series 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + 6 + ⋯ are 1, 3, 6, 10, 15, etc. The nth partial sum is given by a simple formula:

This equation was known to the Pythagoreans as early as the sixth century BCE.[5] Numbers of this form are called triangular numbers, because they can be arranged as an equilateral triangle.

The infinite sequence of triangular numbers diverges to +∞, so by definition, the infinite series 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + ⋯ also diverges to +∞. The divergence is a simple consequence of the form of the series: the terms do not approach zero, so the series diverges by the term test.

Summability

editAmong the classical divergent series, 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + ⋯ is relatively difficult to manipulate into a finite value. Many summation methods are used to assign numerical values to divergent series, some more powerful than others. For example, Cesàro summation is a well-known method that sums Grandi's series, the mildly divergent series 1 − 1 + 1 − 1 + ⋯, to 1/2. Abel summation is a more powerful method that not only sums Grandi's series to 1/2, but also sums the trickier series 1 − 2 + 3 − 4 + ⋯ to 1/4.

Unlike the above series, 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + ⋯ is not Cesàro summable nor Abel summable. Those methods work on oscillating divergent series, but they cannot produce a finite answer for a series that diverges to +∞.[6] Most of the more elementary definitions of the sum of a divergent series are stable and linear, and any method that is both stable and linear cannot sum 1 + 2 + 3 + ⋯ to a finite value . More advanced methods are required, such as zeta function regularization or Ramanujan summation. It is also possible to argue for the value of −+1/12 using some rough heuristics related to these methods.

Heuristics

editSrinivasa Ramanujan presented two derivations of "1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + ⋯ = −+1/12" in chapter 8 of his first notebook.[7][8][9] The simpler, less rigorous derivation proceeds in two steps, as follows.

The first key insight is that the series of positive numbers 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + ⋯ closely resembles the alternating series 1 − 2 + 3 − 4 + ⋯. The latter series is also divergent, but it is much easier to work with; there are several classical methods that assign it a value, which have been explored since the 18th century.[10]

In order to transform the series 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + ⋯ into 1 − 2 + 3 − 4 + ⋯, one can subtract 4 from the second term, 8 from the fourth term, 12 from the sixth term, and so on. The total amount to be subtracted is 4 + 8 + 12 + 16 + ⋯, which is 4 times the original series. These relationships can be expressed using algebra. Whatever the "sum" of the series might be, call it c = 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + ⋯. Then multiply this equation by 4 and subtract the second equation from the first:

The second key insight is that the alternating series 1 − 2 + 3 − 4 + ⋯ is the formal power series expansion (for x at point 0) of the function 1/(1 + x)2 which is 1 − 2x + 3x^2 − 4x^3 + ⋯ evaluated with x defined as 1. Accordingly, Ramanujan writes

Dividing both sides by −3, one gets c = −+1/12.

Generally speaking, it is incorrect to manipulate infinite series as if they were finite sums. For example, if zeroes are inserted into arbitrary positions of a divergent series, it is possible to arrive at results that are not self-consistent, let alone consistent with other methods. In particular, the step 4c = 0 + 4 + 0 + 8 + ⋯ is not justified by the additive identity law alone. For an extreme example, appending a single zero to the front of the series can lead to a different result.[1]

One way to remedy this situation, and to constrain the places where zeroes may be inserted, is to keep track of each term in the series by attaching a dependence on some function.[11] In the series 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + ⋯, each term n is just a number. If the term n is promoted to a function n−s, where s is a complex variable, then one can ensure that only like terms are added. The resulting series may be manipulated in a more rigorous fashion, and the variable s can be set to −1 later. The implementation of this strategy is called zeta function regularization.

Zeta function regularization

editIn zeta function regularization, the series is replaced by the series The latter series is an example of a Dirichlet series. When the real part of s is greater than 1, the Dirichlet series converges, and its sum is the Riemann zeta function ζ(s). On the other hand, the Dirichlet series diverges when the real part of s is less than or equal to 1, so, in particular, the series 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + ⋯ that results from setting s = −1 does not converge. The benefit of introducing the Riemann zeta function is that it can be defined for other values of s by analytic continuation. One can then define the zeta-regularized sum of 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + ⋯ to be ζ(−1).

From this point, there are a few ways to prove that ζ(−1) = −+1/12. One method, along the lines of Euler's reasoning,[12] uses the relationship between the Riemann zeta function and the Dirichlet eta function η(s). The eta function is defined by an alternating Dirichlet series, so this method parallels the earlier heuristics. Where both Dirichlet series converge, one has the identities:

The identity continues to hold when both functions are extended by analytic continuation to include values of s for which the above series diverge. Substituting s = −1, one gets −3ζ(−1) = η(−1). Now, computing η(−1) is an easier task, as the eta function is equal to the Abel sum of its defining series,[13] which is a one-sided limit:

Dividing both sides by −3, one gets ζ(−1) = −+1/12.

Cutoff regularization

editThe method of regularization using a cutoff function can "smooth" the series to arrive at −+1/12. Smoothing is a conceptual bridge between zeta function regularization, with its reliance on complex analysis, and Ramanujan summation, with its shortcut to the Euler–Maclaurin formula. Instead, the method operates directly on conservative transformations of the series, using methods from real analysis.

The idea is to replace the ill-behaved discrete series with a smoothed version

where f is a cutoff function with appropriate properties. The cutoff function must be normalized to f(0) = 1; this is a different normalization from the one used in differential equations. The cutoff function should have enough bounded derivatives to smooth out the wrinkles in the series, and it should decay to 0 faster than the series grows. For convenience, one may require that f is smooth, bounded, and compactly supported. One can then prove that this smoothed sum is asymptotic to −+1/12 + CN2, where C is a constant that depends on f. The constant term of the asymptotic expansion does not depend on f: it is necessarily the same value given by analytic continuation, −+1/12.[1]

Ramanujan summation

editThe Ramanujan sum of 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + ⋯ is also −+1/12. Ramanujan wrote in his second letter to G. H. Hardy, dated 27 February 1913:

- "Dear Sir, I am very much gratified on perusing your letter of the 8th February 1913. I was expecting a reply from you similar to the one which a Mathematics Professor at London wrote asking me to study carefully Bromwich's Infinite Series and not fall into the pitfalls of divergent series. ... I told him that the sum of an infinite number of terms of the series: 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + ⋯ = −+1/12 under my theory. If I tell you this you will at once point out to me the lunatic asylum as my goal. I dilate on this simply to convince you that you will not be able to follow my methods of proof if I indicate the lines on which I proceed in a single letter. ..."[14]

Ramanujan summation is a method to isolate the constant term in the Euler–Maclaurin formula for the partial sums of a series. For a function f, the classical Ramanujan sum of the series is defined as

where f(2k−1) is the (2k − 1)th derivative of f and B2k is the (2k)th Bernoulli number: B2 = 1/6, B4 = −+1/30, and so on. Setting f(x) = x, the first derivative of f is 1, and every other term vanishes, so[15]

To avoid inconsistencies, the modern theory of Ramanujan summation requires that f is "regular" in the sense that the higher-order derivatives of f decay quickly enough for the remainder terms in the Euler–Maclaurin formula to tend to 0. Ramanujan tacitly assumed this property.[15] The regularity requirement prevents the use of Ramanujan summation upon spaced-out series like 0 + 2 + 0 + 4 + ⋯, because no regular function takes those values. Instead, such a series must be interpreted by zeta function regularization. For this reason, Hardy recommends "great caution" when applying the Ramanujan sums of known series to find the sums of related series.[16]

Failure of stable linear summation methods

editA summation method that is linear and stable cannot sum the series 1 + 2 + 3 + ⋯ to any finite value. (Stable means that adding a term at the beginning of the series increases the sum by the value of the added term.) This can be seen as follows. If

then adding 0 to both sides gives

by stability. By linearity, one may subtract the second equation from the first (subtracting each component of the second line from the first line in columns) to give

Adding 0 to both sides again gives

and subtracting the last two series gives

contradicting stability.

Therefore, every method that gives a finite value to the sum 1 + 2 + 3 + ⋯ is not stable or not linear.[17]

Physics

editIn bosonic string theory, the attempt is to compute the possible energy levels of a string, in particular, the lowest energy level. Speaking informally, each harmonic of the string can be viewed as a collection of D − 2 independent quantum harmonic oscillators, one for each transverse direction, where D is the dimension of spacetime. If the fundamental oscillation frequency is ω, then the energy in an oscillator contributing to the nth harmonic is nħω/2. So using the divergent series, the sum over all harmonics is −ħω(D − 2)/24. Ultimately it is this fact, combined with the Goddard–Thorn theorem, which leads to bosonic string theory failing to be consistent in dimensions other than 26.[18]

The regularization of 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + ⋯ is also involved in computing the Casimir force for a scalar field in one dimension.[19] An exponential cutoff function suffices to smooth the series, representing the fact that arbitrarily high-energy modes are not blocked by the conducting plates. The spatial symmetry of the problem is responsible for canceling the quadratic term of the expansion. All that is left is the constant term −1/12, and the negative sign of this result reflects the fact that the Casimir force is attractive.[20]

A similar calculation is involved in three dimensions, using the Epstein zeta-function in place of the Riemann zeta function.[21]

History

editIt is unclear whether Leonhard Euler summed the series to −+1/12. According to Morris Kline, Euler's early work on divergent series relied on function expansions, from which he concluded 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + ⋯ = ∞.[22] According to Raymond Ayoub, the fact that the divergent zeta series is not Abel-summable prevented Euler from using the zeta function as freely as the eta function, and he "could not have attached a meaning" to the series.[23] Other authors have credited Euler with the sum, suggesting that Euler would have extended the relationship between the zeta and eta functions to negative integers.[24][25][26] In the primary literature, the series 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + ⋯ is mentioned in Euler's 1760 publication De seriebus divergentibus alongside the divergent geometric series 1 + 2 + 4 + 8 + ⋯. Euler hints that series of this type have finite, negative sums, and he explains what this means for geometric series, but he does not return to discuss 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + ⋯. In the same publication, Euler writes that the sum of 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + ⋯ is infinite.[27]

In popular media

editDavid Leavitt's 2007 novel The Indian Clerk includes a scene where Hardy and Littlewood discuss the meaning of this series. They conclude that Ramanujan has rediscovered ζ(−1), and they take the "lunatic asylum" line in his second letter as a sign that Ramanujan is toying with them.[28]

Simon McBurney's 2007 play A Disappearing Number focuses on the series in the opening scene. The main character, Ruth, walks into a lecture hall and introduces the idea of a divergent series before proclaiming, "I'm going to show you something really thrilling", namely 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + ⋯ = −+1/12. As Ruth launches into a derivation of the functional equation of the zeta function, another actor addresses the audience, admitting that they are actors: "But the mathematics is real. It's terrifying, but it's real."[29][30]

In January 2014, Numberphile produced a YouTube video on the series, which gathered over 1.5 million views in its first month.[31] The 8-minute video is narrated by Tony Padilla, a physicist at the University of Nottingham. Padilla begins with 1 − 1 + 1 − 1 + ⋯ and 1 − 2 + 3 − 4 + ⋯ and relates the latter to 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + ⋯ using a term-by-term subtraction similar to Ramanujan's argument.[32] Numberphile also released a 21-minute version of the video featuring Nottingham physicist Ed Copeland, who describes in more detail how 1 − 2 + 3 − 4 + ⋯ = 1/4 as an Abel sum, and 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + ⋯ = −+1/12 as ζ(−1).[33] After receiving complaints about the lack of rigour in the first video, Padilla also wrote an explanation on his webpage relating the manipulations in the video to identities between the analytic continuations of the relevant Dirichlet series.[34]

In The New York Times coverage of the Numberphile video, mathematician Edward Frenkel commented: "This calculation is one of the best-kept secrets in math. No one on the outside knows about it."[31]

Coverage of this topic in Smithsonian magazine describes the Numberphile video as misleading and notes that the interpretation of the sum as −+1/12 relies on a specialized meaning for the equals sign, from the techniques of analytic continuation, in which equals means is associated with.[35] The Numberphile video was critiqued on similar grounds by German mathematician Burkard Polster on his Mathologer YouTube channel in 2018, his video receiving 2.7 million views by 2023.[36]

References

edit- ^ a b c d Tao, Terence (April 10, 2010), The Euler–Maclaurin formula, Bernoulli numbers, the zeta function, and real-variable analytic continuation, retrieved January 30, 2014.

- ^ Lepowsky, J. (1999). "Vertex operator algebras and the zeta function". In Naihuan Jing and Kailash C. Misra (ed.). Recent Developments in Quantum Affine Algebras and Related Topics. Contemporary Mathematics. Vol. 248. pp. 327–340. arXiv:math/9909178. Bibcode:1999math......9178L..

- ^ Tong, David (February 23, 2012). "String Theory". pp. 28–48. arXiv:0908.0333 [hep-th].

- ^ Gannon, Terry (April 2010), Moonshine Beyond the Monster: The Bridge Connecting Algebra, Modular Forms and Physics, Cambridge University Press, p. 140, ISBN 978-0521141888.

- ^ Pengelley, David J. (2002). "The bridge between the continuous and the discrete via original sources". In Otto Bekken; et al. (eds.). Study the Masters: The Abel-Fauvel Conference. National Center for Mathematics Education, University of Gothenburg, Sweden. p. 3. ISBN 978-9185143009..

- ^ Hardy 1949, p. 10.

- ^ Ramanujan's Notebooks, retrieved January 26, 2014

- ^ Abdi, Wazir Hasan (1992), Toils and triumphs of Srinivasa Ramanujan, the man and the mathematician, National, p. 41

- ^ Berndt, Bruce C. (1985), Ramanujan's Notebooks: Part 1, Springer-Verlag, pp. 135–136

- ^ Euler, Leonhard (2006). "Translation with notes of Euler's paper: Remarks on a beautiful relation between direct as well as reciprocal power series". Translated by Willis, Lucas; Osler, Thomas J. The Euler Archive. Retrieved 2007-03-22. Originally published as Euler, Leonhard (1768). "Remarques sur un beau rapport entre les séries des puissances tant directes que réciproques". Mémoires de l'Académie des Sciences de Berlin (in French). 17: 83–106.

- ^ Promoting numbers to functions is identified as one of two broad classes of summation methods, including Abel and Borel summation, by Knopp, Konrad (1990) [1922]. Theory and Application of Infinite Series. Dover. pp. 475–476. ISBN 0-486-66165-2.

- ^ Stopple, Jeffrey (2003), A Primer of Analytic Number Theory: From Pythagoras to Riemann, p. 202, ISBN 0-521-81309-3.

- ^ Knopp, Konrad (1990) [1922]. Theory and Application of Infinite Series. Dover. pp. 490–492. ISBN 0-486-66165-2.

- ^ Aiyangar, Srinivasa Ramanujan (7 September 1995). Ramanujan: Letters and Commentary. p. 53. ISBN 9780821891254.

- ^ a b Berndt, Bruce C. (1985), Ramanujan's Notebooks: Part 1, Springer-Verlag, pp. 13, 134.

- ^ Hardy 1949, p. 346.

- ^ Natiello, Mario A.; Solari, Hernan Gustavo (July 2015), "On the removal of infinities from divergent series", Philosophy of Mathematics Education Journal, 29: 1–11, hdl:11336/46148.

- ^ Barbiellini, Bernardo (1987), "The Casimir effect in conformal field theories", Physics Letters B, 190 (1–2): 137–139, Bibcode:1987PhLB..190..137B, doi:10.1016/0370-2693(87)90854-9.

- ^ See v:Quantum mechanics/Casimir effect in one dimension.[unreliable source?]

- ^ Zee 2003, pp. 65–67.

- ^ Zeidler, Eberhard (2007), "Quantum Field Theory I: Basics in Mathematics and Physics: A Bridge between Mathematicians and Physicists", Quantum Field Theory I: Basics in Mathematics and Physics. A Bridge Between Mathematicians and Physicists, Springer: 305–306, Bibcode:2006qftb.book.....Z, ISBN 9783540347644.

- ^ Kline, Morris (November 1983), "Euler and Infinite Series", Mathematics Magazine, 56 (5): 307–314, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.639.6923, doi:10.2307/2690371, JSTOR 2690371.

- ^ Ayoub, Raymond (December 1974), "Euler and the Zeta Function" (PDF), The American Mathematical Monthly, 81 (10): 1067–1086, doi:10.2307/2319041, JSTOR 2319041, retrieved February 14, 2014.

- ^ Lefort, Jean, "Les séries divergentes chez Euler" (PDF), L'Ouvert (in French) (31), IREM de Strasbourg: 15–25, archived from the original (PDF) on February 22, 2014, retrieved February 14, 2014.

- ^ Kaneko, Masanobu; Kurokawa, Nobushige; Wakayama, Masato (2003), "A variation of Euler's approach to values of the Riemann zeta function" (PDF), Kyushu Journal of Mathematics, 57 (1): 175–192, arXiv:math/0206171, doi:10.2206/kyushujm.57.175, S2CID 54514141, archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-02, retrieved January 31, 2014.

- ^ Sondow, Jonathan (February 1994), "Analytic continuation of Riemann's zeta function and values at negative integers via Euler's transformation of series", Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society, 120 (4): 421–424, doi:10.1090/S0002-9939-1994-1172954-7, retrieved February 14, 2014.

- ^ Barbeau, E. J.; Leah, P. J. (May 1976), "Euler's 1760 paper on divergent series", Historia Mathematica, 3 (2): 141–160, doi:10.1016/0315-0860(76)90030-6.

- ^ Leavitt, David (2007), The Indian Clerk, Bloomsbury, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Complicite (April 2012), A Disappearing Number, Oberon, ISBN 9781849432993.

- ^ Thomas, Rachel (December 1, 2008), "A disappearing number", Plus, retrieved February 5, 2014.

- ^ a b Overbye, Dennis (February 3, 2014), "In the End, It All Adds Up to –1/12", The New York Times, retrieved February 3, 2014.

- ^ ASTOUNDING: 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + ... = –1/12 on YouTube.

- ^ Sum of Natural Numbers (second proof and extra footage) on YouTube.

- ^ Padilla, Tony, What do we get if we sum all the natural numbers?, retrieved February 3, 2014.

- ^ Schultz, Colin (2014-01-31). "The Great Debate Over Whether 1 + 2 + 3 + 4... + ∞ = −1/12". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2016-05-16.

- ^ Polster, Burkard (January 13, 2018). Numberphile v. Math: the truth about 1+2+3+...=-1/12. Retrieved August 31, 2023 – via YouTube.

Bibliography

edit- Berndt, Bruce C.; Srinivasa Ramanujan Aiyangar; Rankin, Robert A. (1995). Ramanujan: letters and commentary. American Mathematical Society. ISBN 0-8218-0287-9.

- Hardy, G. H. (1949). Divergent Series. Clarendon Press.

- Zee, A. (2003). Quantum field theory in a nutshell. Princeton UP. ISBN 0-691-01019-6.

Further reading

edit- Zwiebach, Barton (2004). A First Course in String Theory. Cambridge UP. ISBN 0-521-83143-1. See p. 293.

- Elizalde, Emilio (2004). "Cosmology: Techniques and Applications". Proceedings of the II International Conference on Fundamental Interactions. arXiv:gr-qc/0409076. Bibcode:2004gr.qc.....9076E.

- Watson, G. N. (April 1929), "Theorems stated by Ramanujan (VIII): Theorems on Divergent Series", Journal of the London Mathematical Society, 1, 4 (2): 82–86, doi:10.1112/jlms/s1-4.14.82

External links

edit- Lamb E. (2014), "Does 1+2+3... Really Equal –1/12?", Scientific American Blogs.

- This Week's Finds in Mathematical Physics (Week 124), (Week 126), (Week 147), (Week 213)

- Euler's Proof That 1 + 2 + 3 + ⋯ = −1/12 – by John Baez

- John Baez (September 19, 2008). "My Favorite Numbers: 24" (PDF).

- The Euler-Maclaurin formula, Bernoulli numbers, the zeta function, and real-variable analytic continuation by Terence Tao

- A recursive evaluation of zeta of negative integers by Luboš Motl

- Link to Numberphile video 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + ... = –1/12

- Sum of Natural Numbers (second proof and extra footage) includes demonstration of Euler's method.

- What do we get if we sum all the natural numbers? response to comments about video by Tony Padilla

- Related article from New York Times

- Why –1/12 is a gold nugget follow-up Numberphile video with Edward Frenkel

- Divergent Series: why 1 + 2 + 3 + ⋯ = −1/12 by Brydon Cais from University of Arizona