The Perseus cluster (Abell 426) is a cluster of galaxies in the constellation Perseus. It has a recession speed of 5,366 km/s and a diameter of 863′.[1] It is one of the most massive objects in the known universe, containing thousands of galaxies immersed in a vast cloud of multimillion-degree gas.

| Perseus cluster | |

|---|---|

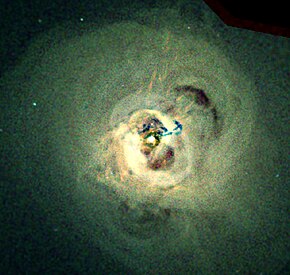

Chandra X-ray Observatory observations of the central regions of the Perseus galaxy cluster. Image is 284 arcsec across. RA 03h 19m 47.60s Dec +41° 30' 37.00" in Perseus. Observation dates: 13 pointings between August 8, 2002 and October 20, 2004. Color code: Energy (Red 0.3–1.2 keV, Green 1.2-2 keV, Blue 2–7 keV). Instrument: ACIS. | |

| Observation data (Epoch J2000) | |

| Constellation(s) | Perseus |

| Right ascension | 03hh 18m [1] |

| Declination | +41° 30′[1] |

| Brightest member | NGC 1275 |

| Number of galaxies | >1000[1] |

| Richness class | 2[2] |

| Bautz–Morgan classification | II-III[2] |

| Redshift | 0.01790 (5 366 km/s)[1] |

| Distance | 73.6 Mpc (240.05 Mly) h−1 0.705[1] |

| X-ray flux | 9.1×10−11 erg s−1 cm−2 (2–10 keV)[1] |

| Other designations | |

| Abell 426,[1] NGC 1275 Cluster,[1] LGG 88 | |

X-radiation from the cluster

editThe Perseus galaxy cluster is the brightest cluster in the sky when observed in the X-ray band.[3]

The cluster contains the radio source 3C 84 that is currently blowing bubbles of relativistic plasma into the core of the cluster. These are seen as holes in an X-ray image of the cluster, as they push away the X-ray emitting gas. They are known as radio bubbles, because they appear as emitters of radio waves due to the relativistic particles in the bubble. The galaxy NGC 1275 is located at the centre of the cluster, where the X-ray emission is brightest.

The first detection of X-ray emission from the Perseus cluster (astronomical designation Per XR-1) occurred during an Aerobee rocket flight on March 1, 1970. The X-ray source may be associated with NGC 1275 (Per A, 3C 84), and was reported in 1971.[4] If the source is NGC 1275, then Lx is about 4 x 1045 ergs/s.[4] More detailed observations from Uhuru confirmed the earlier detection and its source within the Perseus cluster.[5]

Perseus galaxy cluster's Cosmic music note

editIn 2003, a team of astronomers led by Andrew Fabian at Cambridge University discovered one of the deepest notes ever detected, after 53 hours of Chandra observations.[6] No human will actually hear the note, because its time period between oscillations is 9.6 million years, which is 57 octaves below the keys in the middle of a piano.[6] The sound waves appear to be generated by the inflation of bubbles of relativistic plasma by the central active galactic nucleus in NGC 1275. The bubbles are visible as ripples in the X-ray band since the X-ray brightness of the intracluster medium that fills the cluster is strongly dependent on the density of the plasma. In May 2022, NASA reported the sonification (converting astronomical data associated with pressure waves into sound) of the black hole at the center of the Perseus galaxy cluster.[7][8]

A similar case also happens in the nearby Virgo Cluster, generated by an even larger supermassive black hole in the galaxy Messier 87, also detected by Chandra. Like the former, no human will hear the note. The tone is variable, and even lower than those generated by NGC 1275, from 56 octaves below middle C on minor eruptions, to as low as 59 octaves below middle C on major eruptions.[9]

Image gallery

edit-

Euclid space telescope view of the Perseus Cluster. The image shows 1000 galaxies belonging to the cluster, and more than 100 000 additional galaxies further away in the background

-

Perseus Cluster photographed with amateur equipment

-

Perseus Cluster (Chandra X-ray).

-

Turbulence may prevent galaxy clusters from cooling (Chandra X-ray).

-

Composite view of NGC 1275 and the center of the Perseus Cluster (VLA-Radio, Chandra-X-ray, Hubble-Visible, SDSS-Infrared)

See also

edit- Abell catalogue – Astronomical catalogue of galaxy clusters

- List of Abell clusters

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i "NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database". Results for Perseus Cluster. Retrieved 2006-11-28.

- ^ a b Abell, George O.; Corwin, Harold G. Jr.; Olowin, Ronald P. (May 1989). "A catalog of rich clusters of galaxies". Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 70 (May 1989): 1–138. Bibcode:1989ApJS...70....1A. doi:10.1086/191333. ISSN 0067-0049.

- ^ Edge AC; Stewart GC; Fabian AC (1992). "Properties of cooling flows in a flux limited sample of clusters of galaxies". MNRAS. 258: 177–188. Bibcode:1992MNRAS.258..177E. doi:10.1093/mnras/258.1.177.

- ^ a b Fritz G; Davidsen A; Meekins JF; Friedman H (Mar 1971). "Discovery of an X-ray source in Perseus". Astrophys. J. 164 (3): L81–5. Bibcode:1971ApJ...164L..81F. doi:10.1086/180697.

- ^ Forman, W.; Kellogg, E.; Gursky, H.; Tananbaum, H.; Giacconi, R. (1972). "Observations of the Extended X-Ray Sources in the Perseus and Coma Clusters from UHURU". Astrophysical Journal. NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database. 178: 309–316. Bibcode:1972ApJ...178..309F. doi:10.1086/151791. S2CID 120168704.

- ^ a b Fabian, A.C.; Sanders, J.S.; Allen, S.W.; Crawford, C.S.; Iwasawa, K.; Johnstone, R.M.; Schmidt, R.W.; Taylor, G.B. (2003). "A Deep Chandra observation of the Perseus cluster: shocks and ripples". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 344 (3): L43–L47. arXiv:astro-ph/0306036. Bibcode:2003MNRAS.344L..43F. doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.2003.06902.x. S2CID 11086312.

- ^ Watzke, Megan; Porter, Molly; Mohon, Lee (4 May 2022). "New NASA Black Hole Sonifications with a Remix". NASA. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (7 May 2022). "Hear the Weird Sounds of a Black Hole Singing - As part of an effort to "sonify" the cosmos, researchers have converted the pressure waves from a black hole into an audible ... something". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ Roy, Steve; Watzke, Megan (October 2006). "Chandra Views Black Hole Musical: Epic But Off-Key". Chandra X-Ray Observatory. Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

External links

edit- The Perseus Cluster on WikiSky: DSS2, SDSS, GALEX, IRAS, Hydrogen α, X-Ray, Astrophoto, Sky Map, Articles and images

- NASA Astronomy Picture of the Day: Sound waves in Perseus (8 December 2005)

- NASA Astronomy Picture of the Day: A Note on the Perseus Cluster (12 September 2003)

- NASA Astronomy Picture of the Day: Much better version of Perseus cluster (12 July 2011)

- Fabian, A.C., et al. A deep Chandra observation of the Perseus cluster: shocks and ripples. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. Vol. 344 (2003): L43 (arXiv:astro-ph/0306036v2).

- The galaxy cluster Abell 426 (Perseus). A catalogue of 660 galaxy positions, isophotal magnitudes and morphological types, Brunzendorf, J.; Meusinger, H., Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement, v.139, p. 141–161, 1999.

- The galaxy cluster Abell 426 (Perseus). A deep image of Abell 426

- Space.com article about "Sound of a Black Hole." in the Perseus cluster

- http://aida.astroinfo.org/

- Perseus A: Mysterious X-ray Signal Intrigues Astronomers

- The clickable Perseus cluster