Slavery in Egypt existed up until the early 20th century. It differed from the previous slavery in ancient Egypt, being managed in accordance with Islamic law from the conquest of the Caliphate in the 7th century until the practice stopped in the early 20th-century, having been gradually phased out when the slave trade was banned in the late 19th century. British pressure led to the abolishment of slavery trade successively between 1877 and 1884. Slavery itself was not abolished, but it gradually died out after the abolition of the slave trade, since no new slaves could be legally acquired, and existing slaves where given the right to apply for freedom. Existing slaves were noted as late as the 1930s.

During the Islamic history of Egypt, slavery were mainly focused on three categories: male slaves used for soldiers and bureaucrats, female slaves used for sexual slavery as concubines, and female slaves and eunuchs used for domestic service in harems and private households. At the end of the period, there were a growing agricultural slavery. The people enslaved in Egypt during Islamic times mostly came from Europe and Caucasus (which were referred to as "white"), or from the Sudan and Africa South of the Sahara through the Trans-Saharan slave trade (which were referred to as "black").

To this day, Egypt remains a source, transit, and destination country for human trafficking, particularly forced labor and forced prostitution (cf. human trafficking in Egypt).

Abbasid Egypt: 750–935

editEgypt was under the Abbasid Caliphate in 750–935. The institution of slavery therefore followed the institution of slavery in the Abbasid Caliphate, although it did have its own local character.

Slave trade

editOne slave route was from people with whom Egypt had a treaty. Egypt and Nubia maintained peace on the basis of the famous Baqṭ treaty, in which Nubia annually supplied slaves to Egypt, and Egypt textiles and wheat to Nubia.[1] The baqt did not allow for direct slave raids to Nubia, however Egypt did purchase Nubian slaves captured by the Buja tribes living in the Eastern Desert of Nubia, as well as Buja slaves captured by Nubians; Egypt also conducted slave raids to Nubia or Buja whenever they broke the conditions of the treaty. Private Egyptian slave traders also conducted slave raids from Egypt's African hinterland using local violations of the peace agreements as a pretext.[1] Egyptian slave traders often gave wrong origin of their captives on the slave market, making it impossible to know if the slaves had been captured from a people with whom Egypt had a peace agreement.[1]

A second route was from areas with whom Egypt had no treaty, which in Islamic law made slave raids legal. Slave merchants also traded in people captured from nations with whom Muslim authorities had no peace agreement. The History of the Patriarchs noted that slave raides where conducted against the coasts of Byzantine Asia Minor and Europe, during which "Muslims carried off the Byzantines from their lands and brought a great number of them to Egypt (or Fusṭāṭ [Miṣr])".[1] The 10th-century Ḥudūd al-ʿālam claims that Egyptian merchants kidnapped children from the "Blacks" south of Nubia, castrating the boys before trafficking them into Egypt.[1]

A third route was when slave merchant illegally captured other Egyptians, which was forbidden by law. The captured Egyptians were normally either non-Muslim Egyptians, such as Coptic Christians, or the children of black former slaves.[1]

Slave market

editIn this period, the perhaps most significant slave market place in Egypt was Fusṭāṭ. Slave merchants from the Near East, Byzantium, Europe, North Africa and the Mediterranean islands trafficked and sold slaves in Egypt, where according to the Egyptian jurist Aṣbagh b. al-Faraj (d. 839) "people desire above all imported slaves",[1] and among the slaves trafficked were slaves of Slavic, European or Anatolian, Berber, and Sudanic African origin.[1] The merchants sold eunuchs and "slave women (jawārī) and female servants (waṣāʾif)", and slaves are mentioned as perform extra-domestic tasks, ran errands, delivered or collected messages or goods, assisted their masters on business journeys or managed affairs during their masters absence, and was used as sex slaves (concubines).[1]

During this period, slaves in Egypt were either born into slavery, or captives of slavers had who imported them from outside the Realm of Islam, and preserved documents suggest that it was imported slaves who dominated Egypt's slave market.[1] Islam's encouragement to manumit slaves, and the free status granted to children a slave and master (coupled with the fact that most children born to slaves had free fathers), indicate that Egypt was dependent upon a steady flow of new slaves to uphold the slave population, since few slaves born to slaves became slaves themselves[1] unless they were born to two slaves rather than to a slave woman and a free man.

Fatimid Caliphate: 909–1171

editDuring the Fatimid Caliphate (909–1171) slaves were trafficked to Egypt via several routes from non-Islamic lands in the South, North, West and East. The system of military slavery expanded during this time period, which created a bigger need for male slaves for use of military slavery. Female slaves were used for sexual slavery as concubines or as domestic servants.

Slave trade

editThe Trans-Saharan slave trade continued during the Mamluk Sultanate. Egypt was provided with Black African slaves from the Sudan via their centuries old Baqt treaty until the 14th-century.

European saqaliba slaves where provided to Egypt via several routes. The Venetian Balkan slave trade expanded significantly during this time period. The al-Andalus slave trade also provided European slaves, originally imported via the Prague slave trade.

Slave market

editFemale slaves

editFemale slaves were primarily used as either domestic servants, or as concubines (sex slaves).

The slave market classified the slave in accordance with racial stereotypes; Berber slave women were seen as ideal for housework, sexual services and childbearing; black slave women as docile, robust and excellent wet nurses; Byzantine (Greek) as slaves who could be entrusted with valuables; Persian women as good child-minders; Arab slave women as accomplished singers, while Indian and Armenian girls were seen as hard to manage and control; the younger girls, the more attractive on the market.[2]

Male slaves

editMale slaves were used for both hard labor, eunuch service, and military slavery. The system of military slaver grew in importance during this time period.

In the Isma'ili Fatimid Caliphate (909–1171 CE), eunuchs played major roles in the politics of the caliphate's court within the institution of slavery in the Fatimid Caliphate. These eunuchs were normally purchased from slave auctions and typically came from a variety of Arab and non-Arab minority ethnic groups. In some cases, they were purchased from various noble families in the empire, which would then connect those families to the caliph. Generally, though, foreign slaves were preferred, described as the "ideal servants".[3]

Once enslaved, eunuchs were often placed into positions of significant power in one of four areas: the service of the male members of the court; the service of the Fatimid harem, or female members of the court; administrative and clerical positions; and military service.[4] For example, during the Fatimid occupation of Cairo, Egyptian eunuchs controlled military garrisons (shurta) and marketplaces (hisba), two positions beneath only the city magistrate in power. However, the most influential Fatimid eunuchs were the ones in direct service to the caliph and the royal household as chamberlains, treasurers, governors, and attendants.[5] Their direct proximity to the caliph and his household afforded them a great amount of political sway. One eunuch, Jawdhar, became hujja to Imam-Caliph al-Qa'im, a sacred role in Shia Islam entrusted with the imam's choice of successor upon his death.[6]

There were several other eunuchs of high regard in Fatimid history, mainly being Abu'l-Fadi Rifq al-Khadim and Abu'l-Futuh Barjawan al-Ustadh.[7] Rifq was an African eunuch general who served as governor of the Damascus until he led an army of 30,000 men in a campaign to expand Fatimid control northeast to the city of Aleppo, Syria. He was noted for being able to unite a diverse group of Africans, Arabs, Bedouins, Berbers, and Turks into one coherent fight force which was able to successfully combat the Mirdasids, Bedouins, and Byzantines.

Barjawan was a European eunuch during late Fatimid rule who gained power through his military and political savvy which brought peace between them and the Byzantine empire. Moreover, he squashed revolts in the Libya and the Levant. Given his reputation and power in the court and military he took the reins of the caliphate from his then student al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah; then ruled as the de facto Regent 997 CE. His usurpation of power from the caliph resulted in his assassination in 1000 CE on the orders of al-Hakim.

Fatimid harem

editThe Fatimid Caliphate (909–1171) built upon the established model of the Abbasid harem. The Abbasid harem system came to be a role model for the harems of later Islamic rulers, and the same model can be found in subsequent Islamic nations during the Middle Ages, including the harem of the Fatimid Caliphate in Egypt. The Fatimid harem consisted of the same model as the Abbasid harem, and was organized in a model in which the mother took the first rank, followed by slave concubines who became umm walad when giving birth; enslaved female Jawaris entertainers, enslaved female stewardesses named qahramana's, and eunuchs.[8]

The highest ranked woman in the Fatimid harem were normally the mother of the Caliph, or alternatively the mother of the heir or a female relative, who was given the title sayyida or al-sayyida al-malika ("queen").[9] The consorts of the Caliph were originally slave-girls whom the Caliph either married or used as concubines (sex slaves); in either case, a consort of the Caliph was referred to as jiha or al-jiha al-aliya ("Her Highness").[9] The concubines of the Fatimid Caliphs were in most cases of Christian origin, described as beautiful singers, dancers and musicians; they were often the subject of love poems, but also frequently accused of manipulating the Caliph.[10] The third rank harem women were slave-girls trained in singing, dancing and playing music to perform as entertainers; this category was sometimes given as diplomatic gifts between male power holders. The lowest rank of harem women were the slave-girls selected to become servants and performed a number of different tasks in the harem and royal household; these women were called shadadat and had some contact with the outside world, as they trafficked goods from the outside world to the harem via the underground tunnels known as saradib.[11]

All (slave) women employed at court were called mustakhdimat or qusuriyyat; women employed in the royal household were called muqimat and those employed in the royal workshops were in Fustat or Qarafa were called munqaqitat.[12] Slave women worked in royal workshops, arbab al-san'i min al-qusuriyyat, which manufactured clothing and food; those employed at the public worshops were called zahir and those working in the workshops who manufactured items exclusively for the royal household were called khassa.[13] There were often about thirty slave women in each workshop who worked under the supervision of a female slave called zayn al-khuzzan, a position normally given a Greek slave woman.[14]

The enslaved eunuchs managed the women of the harem, guarded them, informed them and reported on them to the Caliph, and acted as their link to the outside world.[15]

The harem of both the Caliph himself as well as other male members of the upper classes could include thousands of slaves: the vizier Ibn for example had a household of 800 concubines and 4,000 male bodyguards.[16]

Ayyubid Sultanate: 1171–1250

editThe Ayyubid Sultanate (1171–1250) included both Egypt and Syria, and the institution of slavery in these areas thus had a shared history during the Ayyubid dynasty.

Slave trade

editAfrican slaves were transported in to Egypt via the slave trade from the Sudan. The baqt treaty was still famously functioning during this time period. The Trans-Saharan slave trade provided African slaves from the West.

The Red Sea slave trade from the provided slaves to the East coast of Egypt. These were mainly Africans. However, there are also Indians noted to have been transported to Egypt via the Red Sea slave trade.

The Venetian slave trade exported slaves to Egypt primarily via the now Balkan slave trade during this time period.

Christian captives from the Crusader states are known to have been enslaved during the two centuries of Christian Crusader rule. This included not only male warriors but also civilians such as women and children. A famous incident was the Siege of Jerusalem (1187). 15,000 of those who could not pay the ransom were sold into slavery. According to Imad ad-Din al-Isfahani, 7,000 of them were men and 8,000 were women and children.[17]

Turkish and other Asian slaves were exported to Egypt from Central Asia via the Bukhara slave trade. Turkish men were particularly valued as slave soldiers.

Slave market

editThere was a numberical superiority of female slaves over male slaves to Egypt.[18]

Female slaves were primarily used as either domestic maids or as concubines (sex slaves). Shajar al-Durr became one of the most famous former slave concubines of the Royal Ayyubid harem.

A significant market for male slaves to Egypt was the institution of mamluk military slavery, an institution of major importance in the Ayyubid Sultanate. Many of the slave soldiers were of either Turkish or Circassian origin.

Mamluk Sultanate: 1250–1517

editDuring the Mamluk Sultanate era (1250–1517), society in Egypt was founded upon a system of military slavery. Male slaves trafficked for use as military slaves, mamluk, were a dominating social class in Egypt. Aside from mamluk military slavery, female slaves were used for sexual slavery and domestic maid service.

Slave trade

editThe Trans-Saharan slave trade continued during the Mamluk Sultanate. Egypt was provided with Black African slaves via their centuries old Baqt treaty until the 14th-century.

Two main routes from Europe provided Egypt with European slaves. The Balkan slave trade and the Black Sea slave trade, managed via the Venetian slave traders and the Genoese slave traders, provided Egypt with many of the male slaves used as mamluk slave soldiers.

The Balkan slave trade was, alongside the Black Sea slave trade, one of the two main slave supply sources of future Mamluk soldiers to the Mamluk Sultanate in Egypt.[19] While the majority of the slaves trafficked via the Black Sea slave trade to South Europe (Italy and Spain) were girls, since they were intended to become ancillae maid servants, the majority of the slaves, around 2,000 annually, were trafficked to the Egyptian Mamluk Sultanate, and in that case most of them boys, since the Mamluk sultanate needed a constant supply of slave soldiers.[20] From at least 1382 onward, the majority of the mamluks of the Egyptian Mamluk sultanate with slave origin came from the Black Sea slave trade; around a hundred Circassian males intended for mamluks were being trafficked via the Black Sea slave trade until the 19th century.[21]

During the 13th-century, Indian boys, women and girls intended for sexual slavery, were trafficked from India to Arabia and to Egypt across the Red Sea slave trade via Aden.[22]

Slave market

editThe slave market were famously dominated by its most significant and influential category, military slavery. Other categories were the common for slavery in Muslim lands, with women used as sex slaves (harem concubines) and domestic slave maids.

Slavery died out in Western Europe after the 12th century, but the demand for laborers after the Black Death resulted in a revival of slavery in Southern Europe in Italy and in Spain, as well as an increase in the demand for slaves in Egypt.[23] The Italian (Genoese and Venetian) slave trade from the Black Sea had two main routes; from the Crimea to Byzantine Constantiople, and via Crete and the Balearic Islands to Italy and Spain; or to the Mamluk Sultanate in Egypt, which received the majority of the slaves.[24]

Harem slavery

editThe harem of the Mamluk sultans was housed in the Citadel al-Hawsh in the capital of Cairo (1250–1517).

The Mamluk sultanate built upon the established model of the Abbasid harem, as did its predecessor the Fatimid harem. The mother of the sultan was the highest ranked woman of the harem. The consorts of the Sultan were originally slave girls. The female slaves were supplied to the harem by the slave trade as children; they could be trained to perform as singers and dancers in the harem, and some were selected to serve as concubines (sex slaves) of the Sultan, who in some cases chose to marry them.[25] Other slave girls served the consorts of the Sultan in a number of domestic tasks as harem servants, known as qahramana or qahramaniyya.[25] The harem was guarded by enslaved eunuchs, until the 15th-century supplied by the Balkan slave trade and then from the Black Sea slave trade, served as the officials of the harem.

The harem of the Mamluk sultans were initially small and moderate, but Sultan Al-Nasir Muhammad (r. 1293–1341) expanded the harem to a major institution, which came to consummate as much luxury and slaves as the infamously luxurious harem of the preceding Fatimid dynasty. The harem of Sultan Al-Nasir Muhammad expanded ot a larger size than any preceding Mamluk sultan, and he left a harem of 1,200 female slaves at his death, 505 of which were singing girls.[25] He married the slave Tughay (d. 1348), who left 1,000 slave girls and 80 eunuchs at her own death.[25]

Military slavery

editFrom 935 to 1250, Egypt was controlled by dynastic rulers, notably the Ikhshidids, Fatimids, and Ayyubids. Throughout these dynasties, thousands of Mamluk servants and guards continued to be used and even took high offices. The Mamluks were essentially enslaved mercenaries. Originally the Mamluks were slaves of Turkic origin from the Eurasian Steppe,[26][27][28][29] but the institution of military slavery spread to include Circassians,[26][27][28][30] Abkhazians,[31][32][33] Georgians,[26][27][34][35][36] Armenians,[26][27][28][37] and Russians,[28] as well as peoples from the Balkans such as Albanians,[27][38] Greeks,[27] and South Slavs[27][38][39] (see Saqaliba, Balkan slave trade and Black Sea slave trade).

This increasing level of influence among the Mamluk worried the Ayyubids in particular. Because Egyptian Mamluks were enslaved Christians, Islamic rulers did not believe they were true believers of Islam despite fighting for wars on behalf of Islam as slave soldiers.[40]

In 1250, a Mamluk rose to become sultan.[40][41] The Mamluk Sultanate survived in Egypt from 1250 until 1517, when Selim captured Cairo on 20 January. Although not in the same form as under the Sultanate, the Ottoman Empire retained the Mamluks as an Egyptian ruling class and the Mamluks and the Burji family succeeded in regaining much of their influence, but as vassals of the Ottomans.[42][43]

By the 14th century, a significant number of slaves came from sub-Saharan Africa, and racist attitudes occurred, exemplified by the Egyptian historian Al-Abshibi (1388–1446) writing that "[i]t is said that when the [black] slave is sated, he fornicates, when he is hungry, he steals."[44]

Ottoman Egypt: 1517–1805

editThe Mamluk Sultanate was conquered by the Ottoman Empire in 1517. Ottoman Egypt was ruled directly by the Ottoman Empire via Ottoman governors until 1805. Slavery in Ottoman Egypt mainly continued the same system established during the Mamluk Sultanate. White slaves were made in to Mamluk soldiers and their concubines and wives, while Black African slaves were used for domestic service and hard labor.

Slave trade

editThe slave trade to Ottoman Egypt followed already established routes. African slaves were provided via the ancient slave trade from the Sudan and the Trans-Saharan slave trade.

The Balkan slave trade was closed down, but the Black Sea slave trade continued, now managed no longer by Italian slave merchants but by the Crimean Khanate and the Ottoman Empire, known as the Crimean slave trade. Slaves trafficked from the Crimean slave trade could be sold far away in the Mediterranean and the Middle East; a Convent in Sinai in Egypt is for example noted to have bought a male slave originating from Kozlov in Russia.[45]

Slave market

editEgypt in the Ottoman period was still dominated by the Mamluk military slavery. Mamluk soldiers in this period were still often white slaves. While the old supply source of the Balkan slave trade had been closed, male mamluk slaves where often Circassian or from Georgia, trafficked via the Crimean slave trade.[46]

The Mamluk aristocrats, who were themselves often Circassian or from Georgia (trafficked via the Black Sea slave trade), preferred to marry women of similar ethnicity, while black slave women were used as domestic maids, and the majority of the wives and concubines of the Mamluk have been referred to as "white slaves".[47] The white slave women bought to become concubines and wives of the Mamluks were often from the Caucasus (Circassians or Georgian) who were sold to slave traders by their poor parents.[48]

It was common practice for the men of the Egyptian Mamluk upper class to marry a woman who had previously been the slave concubine of either themselves or another Mamluk, and the practice of marrying the concubine or the widow of another Mamluk were a way of normal Mamluk alliance policy. The marriage between Murad Bey and Nafisa al-Bayda, widow of Ali Bey al-Kabir, was an example of this marriage policy, similar to that of Shawikar Qadin, the concubine of Uthman Katkhuda (d. 1736), who were given in marriage by Abd al-Rahman Jawish to Ibrahum Katkhuda (d. 1754) after the death of Uthman Katkhuda.[48]

There was a racial hierarchy among slaves. Male laborers and eunuchs, and female domestic maids were provided via the Trans-Saharan slave trade and the Sudanese slave trade to Egypt.

Muhammad Ali dynasty: 1805–1953

editEgypt became de facto independent during the Muhammad Ali dynasty (1805–1914). Slavery was still significant in Egypt during the 19th-century.

The number of slaves in Egypt has been estimated to be at least 30,000 slaves at any time in the 19th century.[49] In Egypt, the slave concubines in the harems of rich Egyptian men were often Circiassian women, while the concubines of middle-class Egyptians were often Abyssinians; while the male and female domestic slaves of almost all classes of Egyptian society often consisted of Black Africans.[49] Black Africans were also used as slave soldiers as well as enslaved agricultural workers.[49]

The slave trade to Egypt was abolished in two stages between 1877 and 1884. Slavery itself was not abolished, but gradually phased out after the ban of the slave trade, and appear to have died out by the 1930s.

Slave trade

editThe Egyptian slave dealers in Egypt were mainly from the Oases and from Upper Egypt. The slave traders were organized in a guild with a shaykh, and divided into dealers in black and white slaves respectively.[49] Cairo was the main depot of slaves and the base of the slave trade, but the annual mawlid of Ṭanṭā was another important occasion for trading in slaves.[49]

African slaves were trafficked to Egypt via several different routes: from Darfur to Asyūṭ; from Sennar to Isnā; from the area of the White Nile; from Bornu and Wadāy by way of Libya; and, finally, from Abyssinia and the East African by way of the Red Sea.[49] White slaves were trafficked to Egypt from the Black Sea area by way of Istanbul.[49]

After the Alexandria expedition of 1807, 400 British prisoners of war captured by Egyptian forces under Muhammad Ali Pasha were marched into Cairo and were either condemned to hard labor or sold into slavery. Colonel Dravetti, now advising Muhammad Ali in Cairo, persuaded the ruler to release the British prisoners of war as a gesture of goodwill, sparing them the (in the Islamic culture) usual fate of becoming slaves to their captors.[50]

Slave market

editMilitary slavery, for centuries a major use for male slaves, continued to be a main category for the Egyptian slave market until the mid 19th-century. The domestic or harem sector continued to be a main destination for female slaves and eunuchs. A market for agricultural slaves expanded significantly during the 19th-century.

Agricultural slavery

editThe use of Sudanese in agriculture become fairly common under Muhammad Ali of Egypt and his successors. Agricultural slavery was virtually unknown in Egypt at this time, but the rapid expansion of extensive farming under Muhammad Ali and later, the world surge in the price of cotton caused by the American Civil War, were factors creating conditions favourable to the deployment of unfree labour. The slaves worked primarily on estates owned by Muhammad Ali and members of his family, and it was estimated in 1869, that Khedive Isma'il and his family had 2,000 to 3,000 slaves on their main estates as well as hundreds more in their sugar plantations in Upper Egypt.[51]

Harem slavery

editThe royal harem of the Muhammad Ali dynasty of the Khedivate of Egypt (1805–1914) was modelled after Ottoman example, the khedives being the Egyptian viceroys of the Ottoman sultans.

Muhammad Ali was appointed vice roy of Egypt in 1805, and by Imperial Ottoman example assembled a harem of slave concubines in the Palace Citadel of Cairo which, according to a traditional account, made his legal wife Amina Hanim declare herself to henceforth be his wife in name only, when she joined him in Egypt in 1808 and discovered his sex slaves.[52]

Similar to the Ottoman Imperial harem, the harem of the khedive was modelled on a system of polygyny based on slave concubinage, in which each wife or concubine was limited to having one son.[53][54] The women harem slaves mostly came from Caucasus via the Circassian slave trade and were referred to as "white".[53][55]

The khedive's harem was composed of between several hundreds to over a thousand enslaved women, supervised by his mother, the walida pasha,[56] and his four official wives (hanim) and recognized concubines (qadin).[53] However, the majority of the slave women served as domestics to his mother and wives, and could have servant offices such as the bash qalfa, chief servant slave woman of the walida pasha.[53][57] The enslaved female servants of the khedivate harem were manumitted and married off with a trousseau in strategic marriages to the male freedmen or slaves (kul or mamluk) who were trained to become officers and civil servants as freedmen, in order to ensure the fidelity of their husband's to the khedive when they began their military or state official career.[53][58] A minority of the slave women were selected to become the personal servants (concubines) of the khedive, often selected by his mother:[59] they could become his wives, and would become free as an umm walad (or mustawlada) if they had children with their enslaver.[60] Muhammad Ali of Egypt reportedly had at least 25 consorts (wives and concubines),[61] and Khedive Ismail fourteen consorts of slave origin, four of whom where his wives.[53][61]

The Egyptian elite of bureaucrat families, who emulated the khedive, had similar harem customs, and it was noted that it was common for Egyptian upper-class families to have slave women in their harem, which they manumitted to marry off to male protegees.[53][58]

This system slowly and gradually started to change after 1873, when Tewfik Pasha married Emina Ilhamy as his sole consort, making monogamy the fashionable ideal among the elite, after the throne succession had been changed to primogeniture, which favored monogamy.[62] The wedding of Tewfik Pasha and Emina Ilhamy was the first wedding of a prince that were celebrated, since the princes had previously merely taken slave concubines, who they sometimes married afterward.[63] The end of the Circassian slave trade and the elimination of slave concubinage after the Anglo-Egyptian Slave Trade Convention also contributed to the end of the practice of polygyny in the Egyptian and Ottoman upper classes from the 1870s onward.[63] In the mid 19th-century, the Ottoman Tanzimat reforms abolished the custom of training male slaves to become military men and civil servants, and replaced them with free students.[53][64]

Military slavery

editTo prepare for the training of his Sudanese slave army, Muhammad Ali sent a corps of Mamluks to Aswan where, in 1820, he had new barracks built to house them. The head of the military academy at Aswan was a French officer who had served under Napoleon, Colonel Octave-Joseph Anthelme Sève, who became a Muslim and is known in Egyptian history as Sulayman Pasha al-Faransawi. When they arrived in Aswan, each of the Sudanese was vaccinated and given a calico vest, then instructed in Islam. The exact numbers of Sudanese brought to Aswan and Muhammad Ali's other military training centre at Manfalut[65] is not known, but it is certain that a great number died en route. Of those who arrived, many died of fevers, chills and the dryness of the climate. Of an estimated 30,000 Sudanese brought to Aswan in 1822 and 1823, only 3,000 survived.

After 1823, Muhammad Ali's priority was to reduce the cost of garrisoning Sudan, where 10,000 Egyptian infantry and 9,000 cavalries were committed. The Egyptians made increasing use of enslaved Sudanese soldiers to maintain their rule, and relied very heavily on them.[66] A more or less official ratio was established, requiring that Sudan provide 3,000 slaves for every 1,000 soldiers sent to subjugate it. This ratio could not be achieved however because the death rate of slaves delivered to Aswan was so high.[67] Muhammad Ali's Turkish and Albanian troops that partook in the Sudan campaign were not used to weather conditions of the area and attained fevers and dysentery while there with tensions emerging and demands to return to Egypt.[68] In addition the difficulties of capturing and raising an army from Sudanese male slaves during the campaign were reasons that led Muhammad Ali toward eventually recruiting local Egyptians for his armed forces.[68]

Abolition and aftermath

editThe Ottoman Empire granted Egypt the status of an autonomous vassal state or Khedivate in 1867. Isma'il Pasha (Khedive from 1863 to 1879) and Tewfik Pasha (Khedive from 1879 to 1892) governed Egypt as a quasi-independent state under Ottoman suzerainty until the British occupation of 1882, after which it came under British influence. The British initiated an anti-slavery campaign and led policy changes regarding slavery in Egypt.[69]

The Anglo-Egyptian Slave Trade Convention or Anglo-Egyptian Convention for the Abolition of Slavery in 1877 officially banned the slave trade to Sudan, thus formally putting an end on the import of slaves from Sudan.[53][55] Sudan was at this time the main import of male slaves to Egypt. This ban was followed in 1884 by a ban on the import of white women; this law was directed against the import of white women (mainly from Caucasus and usually Circassians via the Circassian slave trade), which were the preferred choice for harem concubines among the Egyptian upper class.[53][55] The import of male slaves from Sudan as soldiers, civil service and eunuchs, as well as the import of female slaves from Caucasus as harem women were the two main sources of slave import to Egypt, thus these laws were, at least on paper, major blows on Slavery in Egypt.[55] Slavery itself was not banned, only the import of slaves.[55] However a ban on the sale on existing slaves was introduced alongside a law giving existing slaves the legal right to apply for manumission at the British Consulate or at four Manumission Bureaus established in different parts of the country, and thousands of slaves used the opportunity.[53][55] British abolitionists in Egypt opened a home for former female slaves to assist them and protect them from falling victim to prostitution, which was in operation from 1884 until 1908.[70]

While slavery as such was not outright banned, the effect of the reforms in practice phased out slavery during the following decades. By the early 20th-century, slavery in Egypt was no longer visibly common place enough to be the target of Western criticism. [71] In 1901 a French observer shared his impression that slavery in Egypt was over "in fact and in law"; the Egyptian census of 1907 no longer listed any slaves, and in 1911 Repression of Slave Trade Departments were closed and transferred to Sudan.[72]

The anti slavery reforms gradually diminished the Khedive harem, though the harem of the Khedive as well as the harems of the elite families still maintained a smaller amount of both male eunuchs as well as slave women until at least World War I.[53][57] Khedive Abbas II of Egypt are noted to have bought six "white female slaves" for his harem in 1894, ten years after this had formally been banned, and his mother still maintained sixty slaves as late as 1931.[53][57]

In 1922, Rashid Rida, editor of the progressive Egyptian newspaper al-Manar, condemned the purchase of Chinese slave girls for concubinage and denied that it should be seen as legitimate.[73]

In the 1930s, Egypt answered the Advisory Committee of Experts on Slavery (ACE) of the League of Nations, who conducted a global slavery investigation in 1934-1939, that there were no longer any slavery in Egypt, and that no new slaves could be imported via the ongoing Red Sea slave trade, since they policed the waters of the Red Sea outside Egypt, preventing any import of slaves via the Red Sea coast.[74]

Gallery

edit-

Englishman William George Browne rode with the Darb Al Arbain caravan in the 1790s; it delivered "Slaves, male and female" to Egypt[75]

-

A depiction of slaves being transported across the Sahara Desert

-

Modern Slave Boat on the Nile (1884)

-

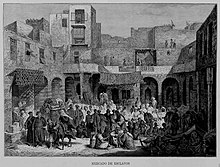

The slave market in Cairo. Wellcome V0050649

-

Slave Market (c.1830) - TIMEA cropped

-

A slave market in Cairo. Drawing by David Roberts, circa 1848.

-

Group of Soudanese slave-girls, recently captured at Cairo

-

Gérôme - the life and works of Jean Léon Gérôme (1892) (14740175136)

-

Negress waiting to be sold in the Slave Bazaar, Cairo - Curzon Robert - 1849

-

Abu Nabut and Negro Slaves in Cairo

-

Abyssinian Female Slave (1878) - TIMEA

-

Dunshway incident prisoners appeal for forgiveness.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Bruning, J. (2020). Slave Trade Dynamics in Abbasid Egypt: The Papyrological Evidence, Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 63(5-6), 682-742. doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/15685209-12341524

- ^ Cortese, D., Calderini, S. (2006). Women And the Fatimids in the World of Islam. Storbritannien: Edinburgh University Press., p. 204

- ^ El Cheikh, N. M. (2017). Guarding the harem, protecting the state: Eunuchs in a fourth/tenth-century Abbasid court. In Celibate and Childless Men in Power (pp. 65–78). Routledge.

- ^ Gul, R., Zafar, N., & Naznin, S. (2021). Legal and Social Status of Eunuchs Islam and Pakistan. sjesr, 4(2), 515–523.

- ^ Höfert, A.; Mesley, M. M.; Tolino, S, eds. (15 August 2017). Celibate and Childless Men in Power: Ruling Eunuchs and Bishops in the Pre-Modern World (1st ed.). Routledge. ISBN 9781315566658.

- ^ Marmon, S. E. (1995). Eunuchs and sacred boundaries in Islamic society. Oxford University Press on Demand.

- ^ Tolino, S. (2017). Eunuchs in the Fatimid empire: Ambiguities, gender and sacredness. In Celibate and Childless Men in Power (pp. 246–267). Routledge.

- ^ El-Azhari, Taef. Queens, Eunuchs and Concubines in Islamic History, 661–1257. Edinburgh University Press, 2019. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctvnjbg3q. Accessed 27 Mar. 2021.

- ^ a b Cortese, D., Calderini, S. (2006). Women And the Fatimids in the World of Islam. Storbritannien: Edinburgh University Press. p. 75

- ^ Cortese, D., Calderini, S. (2006). Women And the Fatimids in the World of Islam. Storbritannien: Edinburgh University Press. p. 76

- ^ Cortese, D., Calderini, S. (2006). Women And the Fatimids in the World of Islam. Storbritannien: Edinburgh University Press. p. 82

- ^ Cortese, D., Calderini, S. (2006). Women And the Fatimids in the World of Islam. Storbritannien: Edinburgh University Press. 80

- ^ Cortese, D., Calderini, S. (2006). Women And the Fatimids in the World of Islam. Storbritannien: Edinburgh University Press. 80

- ^ Cortese, D., Calderini, S. (2006). Women And the Fatimids in the World of Islam. Storbritannien: Edinburgh University Press. 81

- ^ Cortese, D., Calderini, S. (2006). Women And the Fatimids in the World of Islam. Storbritannien: Edinburgh University Press. p. 80

- ^ Cortese, D., Calderini, S. (2006). Women And the Fatimids in the World of Islam. Storbritannien: Edinburgh University Press. 81

- ^ Malcolm Cameron Lyons, D. E. P. Jackson (1984). Saladin: The Politics of the Holy War. Cambridge University Press. p. 277. ISBN 9780521317399.

- ^ Hagedorn, J. H. (2019). Slavery in Syria and Egypt, 1200–1500. Tyskland: Bonn University Press.30

- ^ The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 2, AD 500–AD 1420. (2021). (n.p.): Cambridge University Press. pp. 117–120

- ^ Roşu, Felicia (2021). Slavery in the Black Sea Region, c.900–1900 – Forms of Unfreedom at the Intersection Between Christianity and Islam. Studies in Global Slavery, Volume: 11. Brill. p. 32-33

- ^ Eurasian Slavery, Ransom and Abolition in World History, 1200–1860. (2016). Storbritannien: Taylor & Francis. p. 9

- ^ The Palgrave Handbook of Global Slavery Throughout History. (2023). Tyskland: Springer International Publishing. 143

- ^ Roşu, Felicia (2021). Slavery in the Black Sea Region, c.900–1900 – Forms of Unfreedom at the Intersection Between Christianity and Islam. Studies in Global Slavery, Volume: 11. Brill, p. 19

- ^ Roşu, Felicia (2021). Slavery in the Black Sea Region, c.900–1900 – Forms of Unfreedom at the Intersection Between Christianity and Islam. Studies in Global Slavery, Volume: 11. Brill, p. 35-36

- ^ a b c d Levanoni, A. (2021). A Turning Point in Mamluk History: The Third Reign of Al-Nāsir Muḥammad Ibn Qalāwūn (1310-1341). Nederländerna: Brill. p. 184

- ^ a b c d "Warrior kings: A look at the history of the Mamluks". The Report – Egypt 2012: The Guide. Oxford Business Group. 2012. pp. 332–334. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

The Mamluks, who descended from non-Arab slaves who were naturalised to serve and fight for ruling Arab dynasties, are revered as some of the greatest warriors the world has ever known. Although the word mamluk translates as "one who is owned", the Mamluk soldiers proved otherwise, gaining a powerful military standing in various Muslim societies, particularly in Egypt. They would also go on to hold political power for several centuries during a period known as the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt. [...] Before the Mamluks rose to power, there was a long history of slave soldiers in the Middle East, with many recruited into Arab armies by the Abbasid rulers of Baghdad in the ninth century. The tradition was continued by the dynasties that followed them, including the Fatimids and Ayyubids (it was the Fatimids who built the foundations of what is now Islamic Cairo). For centuries, the rulers of the Arab world recruited men from the lands of the Caucasus and Central Asia. It is hard to discern the precise ethnic background of the Mamluks, given that they came from a number of ethnically mixed regions, but most are thought to have been Turkic (mainly Kipchak and Cuman) or from the Caucasus (predominantly Circassian, but also Armenian and Georgian). The Mamluks were recruited forcibly to reinforce the armies of Arab rulers. As outsiders, they had no local loyalties, and would thus fight for whoever owned them, not unlike mercenaries. Furthermore, the Turks and Circassians had a ferocious reputation as warriors. The slaves were either purchased or abducted as boys, around the age of 13, and brought to the cities, most notably to Cairo and its Citadel. Here they would be converted to Islam and would be put through a rigorous military training regime that focused particularly on horsemanship. A code of behaviour not too dissimilar to that of the European knights' Code of Chivalry was also inculcated and was known as Furusiyya. As in many military establishments to this day the authorities sought to instil an esprit de corps and a sense of duty among the young men. The Mamluks would have to live separately from the local populations in their garrisons, which included the Citadel and Rhoda Island, also in Cairo.

- ^ a b c d e f g Stowasser, Karl (1984). "Manners and Customs at the Mamluk Court". Muqarnas. 2 (The Art of the Mamluks). Leiden: Brill Publishers: 13–20. doi:10.2307/1523052. ISSN 0732-2992. JSTOR 1523052. S2CID 191377149.

The Mamluk slave warriors, with an empire extending from Libya to the Euphrates, from Cilicia to the Arabian Sea and the Sudan, remained for the next two hundred years the most formidable power of the Eastern Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean – champions of Sunni orthodoxy, guardians of Islam's holy places, their capital, Cairo, the seat of the Sunni caliph and a magnet for scholars, artists, and craftsmen uprooted by the Mongol upheaval in the East or drawn to it from all parts of the Muslim world by its wealth and prestige. Under their rule, Egypt passed through a period of prosperity and brilliance unparalleled since the days of the Ptolemies. [...] They ruled as a military aristocracy, aloof and almost totally isolated from the native population, Muslim and non-Muslim alike, and their ranks had to be replenished in each generation through fresh imports of slaves from abroad. Only those who had grown up outside Muslim territory and who entered as slaves in the service either of the sultan himself or of one of the Mamluk emirs were eligible for membership and careers within their closed military caste. The offspring of Mamluks were free-born Muslims and hence excluded from the system: they became the awlād al-nās, the "sons of respectable people", who either fulfilled scribal and administrative functions or served as commanders of the non-Mamluk ḥalqa troops. Some two thousand slaves were imported annually: Qipchaq, Azeris, Uzbec Turks, Mongols, Avars, Circassians, Georgians, Armenians, Greeks, Bulgars, Albanians, Serbs, Hungarians.

- ^ a b c d Poliak, A. N. (2005) [1942]. "The Influence of C̱ẖingiz-Ḵẖān's Yāsa upon the General Organization of the Mamlūk State". In Hawting, Gerald R. (ed.). Muslims, Mongols, and Crusaders: An Anthology of Articles Published in the "Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies". Vol. 10. London and New York: Routledge. pp. 27–41. doi:10.1017/S0041977X0009008X. ISBN 978-0-7007-1393-6. JSTOR 609130. S2CID 155480831.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Isichei, Elizabeth (1997). A History of African Societies to 1870. Cambridge University Press. pp. 192. Retrieved 8 November 2008.

- ^ McGregor, Andrew James (2006). A Military History of Modern Egypt: From the Ottoman Conquest to the Ramadan War. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 15. ISBN 978-0275986018.

By the late fourteenth century Circassians from the north Caucasus region had become the majority in the Mamluk ranks.

- ^ А.Ш.Кадырбаев, Сайф-ад-Дин Хайр-Бек – абхазский "король эмиров" Мамлюкского Египта (1517–1522), "Материалы первой международной научной конференции, посвященной 65-летию В.Г.Ардзинба". Сухум: АбИГИ, 2011, pp. 87–95

- ^ Thomas Philipp, Ulrich Haarmann (eds), The Mamluks in Egyptian Politics and Society. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), pp. 115–116.

- ^ Jane Hathaway, The Politics of Households in Ottoman Egypt: The Rise of the Qazdaglis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997, pp. 103–104.

- ^ "Relations of the Georgian Mamluks of Egypt with Their Homeland in the Last Decades of the Eighteenth Century". Daniel Crecelius and Gotcha Djaparidze. Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, Vol. 45, No. 3 (2002), pp. 320–341. ISSN 0022-4995

- ^ Basra, the failed Gulf state: separatism and nationalism in southern Iraq, p. 19, at Google Books By Reidar Visser

- ^ Hathaway, Jane (February 1995). "The Military Household in Ottoman Egypt". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 27 (1): 39–52. doi:10.1017/s0020743800061572. S2CID 62834455.

- ^ Walker, Paul E. Exploring an Islamic Empire: Fatimid History and its Sources (London, I. B. Tauris, 2002)

- ^ a b István Vásáry (2005) Cuman and Tatars, Cambridge University Press.

- ^ T. Pavlidis, A Concise History of the Middle East, Chapter 11: "Turks and Byzantine Decline". 2011

- ^ a b Thomas Philipp & Ulrich Haarmann. The Mamluks in Egyptian Politics and Society.

- ^ David Nicole The Mamluks 1250–1570

- ^ James Waterson, "The Mamluks"

- ^ Thomas Philipp, Ulrich Haarmann (1998). The Mamluks in Egyptian Politics and Society

- ^ Lewis, Bernard (2002). Race and Slavery in the Middle East. Oxford University Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-19-505326-5.

- ^ Davies, Brian (2014). Warfare, State and Society on the Black Sea Steppe, 1500–1700. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-55283-2. p. 25

- ^ Jutta Sperling, Shona Kelly Wray, Gender, Property, and Law in Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Communities in

- ^ Jutta Sperling, Shona Kelly Wray, Gender, Property, and Law in Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Communities in

- ^ a b Mary Ann Fay, Unveiling the Harem: Elite Women and the Paradox of Seclusion in Eighteenth

- ^ a b c d e f g Baer, G. (1967). Slavery in Nineteenth Century Egypt. The Journal of African History, 8(3), 417-441. doi:10.1017/S0021853700007945

- ^ Manley & Ree, p. 76.

- ^ Mowafi 1985, p. 23.

- ^ Cuno, K. M. (2015). Modernizing Marriage: Family, Ideology, and Law in Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Egypt. Syracuse University Press. p. 31-32

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Kenneth M. Cuno: Modernizing Marriage: Family, Ideology, and Law in Nineteenth- and Early ...

- ^ Cuno, K. M. (2015). Modernizing Marriage: Family, Ideology, and Law in Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Egypt. Syracuse University Press. p. 31

- ^ a b c d e f Cuno, K. M. (2015). Modernizing Marriage: Family, Ideology, and Law in Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Egypt. Syracuse University Press. p. 25

- ^ Cuno, K. M. (2015). Modernizing Marriage: Family, Ideology, and Law in Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Egypt. Syracuse University Press. p. 20

- ^ a b c Cuno, K. M. (2015). Modernizing Marriage: Family, Ideology, and Law in Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Egypt. Syracuse University Press. p. 42

- ^ a b Cuno, K. M. (2015). Modernizing Marriage: Family, Ideology, and Law in Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Egypt. Syracuse University Press. p. 26-27

- ^ Cuno, K. M. (2015). Modernizing Marriage: Family, Ideology, and Law in Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Egypt. Syracuse University Press. p. 34

- ^ Cuno, K. M. (2015). Modernizing Marriage: Family, Ideology, and Law in Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Egypt. Syracuse University Press. p. 24

- ^ a b Cuno, K. M. (2015). Modernizing Marriage: Family, Ideology, and Law in Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Egypt. Syracuse University Press. p. 32

- ^ Cuno, K. M. (2015). Modernizing Marriage: Family, Ideology, and Law in Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Egypt. Syracuse University Press. p. 19-20

- ^ a b Cuno, K. M. (2015). Modernizing Marriage: Family, Ideology, and Law in Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Egypt. Syracuse University Press. p. 30

- ^ Cuno, K. M. (2015). Modernizing Marriage: Family, Ideology, and Law in Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Egypt. Syracuse University Press. p. 28

- ^ Flint 1977, p. 256.

- ^ Mowafi 1985, p. 19.

- ^ Fahmy 2002, p. 88.

- ^ a b Fahmy 2002, p. 89.

- ^ "The Harem, Slavery and British Imperial Culture: Anglo-Muslim Relations in the Late-Nineteenth Century, a history book review". archives.history.ac.uk. Retrieved 2024-07-23.

- ^ Indian Ocean Slavery in the Age of Abolition. (2013). USA: Yale University Press.

- ^ Cuno, K. M. (2015). Modernizing Marriage: Family, Ideology, and Law in Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Egypt. Egypten: Syracuse University Press. 25

- ^ Indian Ocean Slavery in the Age of Abolition. (2013). USA: Yale University Press.

- ^ Clarence-Smith, W. G. (2007). Eunuchs and Concubines in the History of Islamic Southeast Asia. Manusya: Journal of Humanities, 10(4), 8-19. https://doi.org/10.1163/26659077-01004001

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 262

- ^ "DARB EL ARBA'IN. THE FORTY DAYS' ROAD | W. B. K. Shaw | download". ur.booksc.me. Retrieved 2022-09-28.

Sources

edit- Fahmy, Khaled (2002). All the Pasha's men: Mehmed Ali, his army and the making of modern Egypt. The American University in Cairo Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-9774246968.

- Flint, John E. (28 January 1977). The Cambridge History of Africa. Vol. 5. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521207010.

- Mowafi, Reda (1 March 1985). Slavery, Slave Trade and Abolition Attempts in Egypt and the Sudan 1820-1882. Humanities Press. ISBN 978-9124313494.