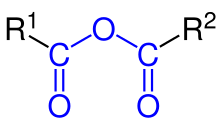

An organic acid anhydride is an acid anhydride that is also an organic compound. An acid anhydride is a compound that has two acyl groups bonded to the same oxygen atom.[1] A common type of organic acid anhydride is a carboxylic anhydride, where the parent acid is a carboxylic acid, the formula of the anhydride being (RC(O))2O. Symmetrical acid anhydrides of this type are named by replacing the word acid in the name of the parent carboxylic acid by the word anhydride.[2] Thus, (CH3CO)2O is called acetic anhydride. Mixed (or unsymmetrical) acid anhydrides, such as acetic formic anhydride (see below), are known, whereby reaction occurs between two different carboxylic acids. Nomenclature of unsymmetrical acid anhydrides list the names of both of the reacted carboxylic acids before the word "anhydride" (for example, the dehydration reaction between benzoic acid and propanoic acid would yield "benzoic propanoic anhydride").[3]

One or both acyl groups of an acid anhydride may also be derived from another type of organic acid, such as sulfonic acid or a phosphonic acid. One of the acyl groups of an acid anhydride can be derived from an inorganic acid such as phosphoric acid. The mixed anhydride 1,3-bisphosphoglyceric acid, an intermediate in the formation of ATP via glycolysis,[4] is the mixed anhydride of 3-phosphoglyceric acid and phosphoric acid. Acidic oxides are also classified as acid anhydrides.

Nomenclature

editThe nomenclature of organic acid anhydrides is derived from the names of the constituent carboxylic acids. In symmetrical acid anhydrides, only the prefix of the original carboxylic acid is used and the suffix "anhydride" is added. For most unsymmetrical acid anhydrides - also called mixed anhydrides- the prefixes from both acids reacted are listed before the suffix, e.g., benzoic propanoic anhydride.[5]

Preparation

editOrganic acid anhydrides are prepared in industry by diverse means. Acetic anhydride is mainly produced by the carbonylation of methyl acetate.[6] Maleic anhydride is produced by the oxidation of benzene or butane. Laboratory routes emphasize the dehydration of the corresponding acids. The conditions vary from acid to acid, but phosphorus pentoxide is a common dehydrating agent:

- 2 CH3COOH + P4O10 → CH3C(O)OC(O)CH3 + "P4O9(OH)2"

In addition to symmetrical, acyclic anhydrides, other classes are recognized as discussed in the following sections.

Mixed anhydrides

editMixed anhydrides have the formula RC(O)OC(O)R'. They tend to redistribute upon heating although acetic formic anhydride can be distilled at one atmosphere.[7] Those containing the acetyl group can be prepared using ketene as an acetylating agent:

- RCO2H + H2C=C=O → RCO2C(O)CH3

Acid chlorides are also effective precursors as illustrated by the reaction with sodium formate:[8]

- CH3C(O)Cl + HCO2Na → HCO2COCH3 + NaCl

Cyclic anhydrides

editExamples include maleic anhydride and succinic anhydride. Although these five-membered rings form readily.[9][10][11]

Dianhydrides and trianhydrides

editExamples are mostly cyclic anhydrides:

- 1,2,3,4-butanetetracarboxylic dianhydride produced by dehydration of 1,2,3,4-butanetetracarboxylic acid.

- naphthalenetetracarboxylic dianhydride

- 1,2,4,5-Benzenetetracarboxylic dianhydride and 1,2,3,4-Benzenetetracarboxylic dianhydride

- Mellitic anhydride, a trianhydride

These compounds are sometimes useful crosslinking agents.

Reactions

editAcid anhydrides are a source of reactive acyl groups, and their reactions and uses resemble those of acyl halides. Acid anhydrides tend to be less electrophilic than acyl chlorides, and only one acyl group is transferred per molecule of acid anhydride, which leads to a lower atom efficiency. The low cost, however, of acetic anhydride makes it a common choice for acetylation reactions.

In reactions with alcohols and amines, the reactions afford equal amounts of the acylated product and the carboxylic acid:

- RC(O)OC(O)R + R'OH → RC(O)OR' + RCO2H

- RC(O)OC(O)R + R'2NH → RC(O)NR'2 + RCO2H

Similarly, in Friedel-Crafts acylation of arenes (ArH):

- RC(O)OC(O)R + ArH → RC(O)Ar + RCO2H

As with acid halides, anhydrides can also react with carbon nucleophiles to furnish ketones and/or tertiary alcohols, and can participate in both the Friedel–Crafts acylation and the Weinreb ketone synthesis. Unlike acid halides, however, anhydrides do not react with Gilman reagents.[citation needed]

The reactivity of anhydrides can be increased by using a catalytic amount of N,N-dimethylaminopyridine ("DMAP") or even pyridine.[12]

First, DMAP (2) attacks the anhydride (1) to form a tetrahedral intermediate, which collapses to eliminate a carboxylate ion to give amide 3. This intermediate amide is more activated towards nucleophilic attack than the original anhydride, because dimethylaminopyridine is a better leaving group than a carboxylate. In the final set of steps, a nucleophile (Nuc) attacks 3 to give another tetrahedral intermediate. When this intermediate collapses to give the product 4, the pyridine group is eliminated and its aromaticity is restored – a powerful driving force, and the reason why the pyridine compound is a better leaving group than a carboxylate ion.

For prochiral cyclic anhydrides, the alcoholysis reaction can be conducted asymmetrically.[13]

Applications and occurrence of acid anhydrides

edit- Illustrative acid anhydrides

-

Acetic anhydride is produced on a large scale for many applications.

-

Naphthalenetetracarboxylic dianhydride, a building block for complex organic compounds, is an example of a dianhydride.

-

Maleic anhydride is a cyclic anhydride, widely used to make industrial coatings.

-

ATP in its protonated form is an anhydride derived from phosphoric acid.

-

The "mixed anhydride" 1,3-bisphosphoglyceric acid occurs widely in metabolic pathways.

-

3'-Phosphoadenosine-5'-phosphosulfate (PAPS) is a mixed anhydride of sulfuric and phosphoric acids and is the most common coenzyme in biological sulfate transfer reactions.

Acetic anhydride is a major industrial chemical widely used for preparing acetate esters, e.g. cellulose acetate. Maleic anhydride is the precursor to various resins by copolymerization with styrene. Maleic anhydride is a dienophile in the Diels-Alder reaction.[7]

Dianhydrides, molecules containing two acid anhydride functions, are used to synthesize polyimides and sometimes polyesters[14] and polyamides.[15] Examples of dianhydrides: pyromellitic dianhydride (PMDA), 3,3’, 4,4’ - oxydiphtalic dianhydride (ODPA), 3,3’, 4,4’-benzophenone tetracarboxylic dianhydride (BTDA), 4,4’-diphtalic (hexafluoroisopropylidene) anhydride (6FDA), benzoquinonetetracarboxylic dianhydride, ethylenetetracarboxylic dianhydride. Polyanhydrides are a class of polymers characterized by anhydride bonds that connect repeat units of the polymer backbone chain.

Biological occurrence

editNatural products containing acid anhydrides have been isolated from animals, bacteria and fungi.[16][17][18] Examples include cantharidin from species of blister beetle, including the Spanish fly, Lytta vesicatoria, and tautomycin, from the bacterium Streptomyces spiroverticillatus. The maleidride family of fungal secondary metabolites, which possess a wide range of antibiotic and antifungal activity, are alicyclic compounds with maleic anhydride functional groups.[19] A number of proteins in prokaryotes[20] and eukaryotes[21] undergo spontaneous cleavage between the amino acid residues aspartic acid and proline via an acid anhydride intermediate. In some cases, the anhydride may then react with nucleophiles of other cellular components, such as at the surface of the bacterium Neisseria meningitidis or on proteins localized nearby.[22]

Analogues

editNitrogen

editImides are structurally related analogues, where the bridging oxygen is replaced by nitrogen. They are similarly formed by the condensation of dicarboxylic acids with ammonia. The replacement of all oxygen atoms with nitrogen gives imidines, these are a rare functional group which are very prone to hydrolysis.

Sulfur

editSulfur can replace oxygen, either in the carbonyl group or in the bridge. In the former case, the name of the acyl group is enclosed in parentheses to avoid ambiguity in the name,[2] e.g., (thioacetic) anhydride (CH3C(S)OC(S)CH3). When two acyl groups are attached to the same sulfur atom, the resulting compound is called a thioanhydride,[2] e.g., acetic thioanhydride ((CH3C(O))2S).

See also

edit- Base anhydride

- Benzoyl peroxide - structurally similar but chemically very different

References

edit- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "acid anhydrides". doi:10.1351/goldbook.A00072

- ^ a b c Panico, R.; Powell, W. H.; Richer, J. C., eds. (1993). "Recommendation R-5.7.7". A Guide to IUPAC Nomenclature of Organic Compounds. IUPAC/Blackwell Science. pp. 123–25. ISBN 0-632-03488-2.

- ^ "Nomenclature of Anhydrides". 8 November 2013.

- ^ Nelson, D. L.; Cox, M. M. "Lehninger, Principles of Biochemistry" 3rd Ed. Worth Publishing: New York, 2000. ISBN 1-57259-153-6.

- ^ "Nomenclature of Anhydrides". 8 November 2013.

- ^ Zoeller, J. R.; Agreda, V. H.; Cook, S. L.; Lafferty, N. L.; Polichnowski, S. W.; Pond, D. M. "Eastman Chemical Company Acetic Anhydride Process" Catalysis Today (1992), volume 13, pp.73-91. doi:10.1016/0920-5861(92)80188-S

- ^ a b Heimo Held, Alfred Rengstl, Dieter Mayer "Acetic Anhydride and Mixed Fatty Acid Anhydrides" Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry 2002, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a01_065

- ^ Lewis I. Krimen (1970). "Acetic Formic Anhydride". Organic Syntheses. 50: 1. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.050.0001.

- ^ Spanedda, Maria Vittoria; Bourel-Bonnet, Line (2021). "Cyclic Anhydrides as Powerful Tools for Bioconjugation and Smart Delivery" (PDF). Bioconjugate Chemistry. 32 (3): 482–496. doi:10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.1c00023. PMID 33662203.

- ^ Chen, Yonggang; McDaid, Paul; Deng, Li (2003). "Asymmetric Alcoholysis of Cyclic Anhydrides". Chemical Reviews. 103 (8): 2965–2984. doi:10.1021/cr020037x. PMID 12914488.

- ^ González-López, Marcos; Shaw, Jared T. (2009). "Cyclic Anhydrides in Formal Cycloadditions and Multicomponent Reactions". Chemical Reviews. 109 (1): 164–189. doi:10.1021/cr8002714. PMID 19140773.

- ^ Kürti, László; Barbara Czakó (2005). Strategic Applications of Named Reactions in Organic Synthesis. London: Elsevier Academic Press. p. 398. ISBN 0124297854.

- ^ Carsten Bolm, Iuliana Atodiresei, and Ingo Schiffers (2005). "Asymmetric Alcoholysis of Meso-Anhydrides Mediated by Alkaloids". Organic Syntheses. 82: 120. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.082.0120.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chiang, Wen-Yen; Chiang, Wen-Chang (1988-05-05). "Condensation polymerization of multifunctional monomers and properties of related polyester resins. II. Thermal properties of polyester—imide varnishes". Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 35 (6): 1433–1439. doi:10.1002/app.1988.070350603.

- ^ Faghihi, Khalil; Ashouri, Mostafa; Hajibeygi, Mohsen (2013-10-25). "High Temperature and Organosoluble Poly(amide-imide)s Based on 1,4-Bis[4-aminophenoxy]butane and Aromatic Diacids by Direct Polycondensation: Synthesis and Properties". High Temperature Materials and Processes. 32 (5): 451–458. doi:10.1515/htmp-2012-0164. ISSN 2191-0324.

- ^ Saleem, Muhammad; Hussain, Hidayat; Ahmed, Ishtiaq; Draeger, Siegfried; Schulz, Barbara; Meier, Kathrin; Steinert, Michael; Pescitelli, Gennaro; Kurtán, Tibor; Flörke, Ulrich; Krohn, Karsten (February 2011). "Viburspiran, an Antifungal Member of the Octadride Class of Maleic Anhydride Natural Products". European Journal of Organic Chemistry. 2011 (4): 808–812. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201001324.

- ^ Han, Chunguang; Furukawa, Hiroyuki; Tomura, Tomohiko; Fudou, Ryosuke; Kaida, Kenichi; Choi, Bong-Keun; Imokawa, Genji; Ojika, Makoto (24 April 2015). "Bioactive Maleic Anhydrides and Related Diacids from the Aquatic Hyphomycete Tricladium castaneicola". Journal of Natural Products. 78 (4): 639–644. doi:10.1021/np500773s. PMID 25875311.

- ^ Heard, David M.; Tayler, Emyr R.; Cox, Russell J.; Simpson, Thomas J.; Willis, Christine L. (3 January 2020). "Structural and synthetic studies on maleic anhydride and related diacid natural products" (PDF). Tetrahedron. 76 (1): 130717. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2019.130717. hdl:1983/53998d06-9017-4cfb-822b-c6453348000a. S2CID 209714625.

- ^ Chen, Xiaolong; Zheng, Yuguo; Shen, Yinchu (May 2007). "Natural Products with Maleic Anhydride Structure: Nonadrides, Tautomycin, Chaetomellic Anhydride, and Other Compounds". Chemical Reviews. 107 (5): 1777–1830. doi:10.1021/cr050029r. PMID 17439289.

- ^ Kuban, Vojtech (2020). "Structural Basis of Ca 2+-Dependent Self-Processing Activity of Repeat-in-Toxin Proteins". mBio. 11 (2): e00226-20. doi:10.1128/mBio.00226-20. PMC 7078468. PMID 32184239.

- ^ Bell, Christian (2013). "Structure of the repulsive guidance molecule (RGM)-neogenin signaling hub". Science. 341 (6141): 77–80. Bibcode:2013Sci...341...77B. doi:10.1126/science.1232322. PMC 4730555. PMID 23744777.

- ^ Scheu, Arne (2021). "NeissLock provides an inducible protein anhydride for covalent targeting of endogenous proteins". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 717. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12..717S. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-20963-5. PMC 7846742. PMID 33514717.