Adolph Zukor (/ˈzuːkər/; Hungarian: Czukor Adolf; January 7, 1873 – June 10, 1976)[1] was a Hungarian-American film producer best known as one of the three founders of Paramount Pictures.[2] He produced one of America's first feature-length films, The Prisoner of Zenda, in 1913.[3][4]

Adolph Zukor | |

|---|---|

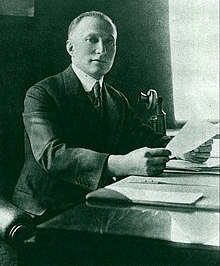

Zukor in 1922 | |

| Born | January 7, 1873 |

| Died | June 10, 1976 (aged 103) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Temple Israel Cemetery, Hastings-on-Hudson, New York |

| Other names | Adolf Zuckery |

| Occupation | Film producer |

| Years active | 1903–1959 |

| Known for | One of the three founders of Paramount Pictures |

| Spouse |

Lottie Kaufman (m. 1897) |

| Children | 2 |

| Family | Marcus Loew (daughter's father-in-law) |

| Signature | |

| |

Early life

editZukor was born to an Ashkenazi Jewish family in Ricse, in the Kingdom of Hungary in January 1873,[5] which was then a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His father, Jacob, who operated a general store, died when he was a toddler, while his mother, Hannah Liebermann, died when he was 7 years old. Adolph and his brother Arthur moved in with Kalman Liebermann, their uncle. Liebermann, a rabbi, expected his nephews to become rabbis, but instead Adolph served a three-year apprenticeship in the dry goods store of family friends. When he was 16, he decided to emigrate to the United States.[3][4] He sailed from Hamburg on the s/s Rugia on March 1[6] and arrived in New York City under the name Adolf Zuckery on March 16, 1891.[7] Like most immigrants, he began modestly. After landing in New York City, he began working in an upholstery shop. A friend then got him a job as an apprentice at a furrier.

Zukor stayed in New York City for two years. When he left to become a "contract" worker, sewing fur pieces and selling them himself, he was 20 years old and an accomplished designer. He was young and adventuresome, and the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago drew him to the Midwest. There he started a fur business. In the second season of operation, Zukor's Novelty Fur Company expanded to 25 men and opened a branch.[8]

Historian Neal Gabler wrote, "one of the stubborn fallacies of movie history is that the men who created the film industry were all impoverished young vulgarians..." Zukor clearly didn't fit this profile. By 1903, he already looked and lived like a wealthy young burgher, and he certainly earned the income of one. He had a commodious apartment at 111th Street and Seventh Avenue in New York City's wealthy German-Jewish section".[8]

In 1918, he moved to New City, Rockland County, New York, where he purchased 300 acres of land from Lawrence Abraham, heir to the A&S Department Stores. Abraham had already built a sizable house, a nine-hole golf course and a swimming pool on this property. Two years later, Zukor bought an additional 500 acres, built a night house, guest house, movie theater, locker room, greenhouses, garages and staff quarters, and hired golf architect A.W. Tillinghast to build an 18-hole championship golf course. Today, Zukor's estate is the private Paramount Country Club.[9]

Early film career

editIn 1903, he became involved in the film industry when his cousin, Max Goldstein, approached him for a loan to invest in a chain of theaters. These theaters were started by Mitchell Mark in Buffalo, New York, and hosted Edisonia Hall. Mark needed investors to expand his chain of theaters. Zukor gave Goldstein the loan and formed a partnership with Mark and Morris Kohn, a friend of Zukor's who also invested in the theaters. Zukor, Mark, and Kohn opened a penny arcade operating as The Automatic Vaudeville Company on 14th Street in New York City. They soon opened branches in Boston, Philadelphia, and Newark, with funding by Marcus Loew.[4][3][10] By 1910, Zukor already owned a nickelodeon chain and became Leow's partner in a theater circuit.[5] Two years later, he sold his shares in Loew's company in order to purchase the French film, Queen Elizabeth.[5]

Famous Players

editIn 1912, Adolph Zukor established Famous Players Film Company—advertising "Famous Players in Famous Plays"—as the American distribution company for the French film production Les Amours de la reine Élisabeth starring Sarah Bernhardt.[11] The following year he obtained the financial backing of the Frohman brothers, the powerful New York City theatre impresarios. Their primary goal was to bring noted stage actors to the screen and Zukor went on to produce The Prisoner of Zenda (1913). He purchased an armory on 26th Street in Manhattan and converted it into Chelsea Studios, a movie studio that is still used today.[12]

In 1916, the company merged with Jesse L. Lasky's company to form Famous Players–Lasky.

Paramount Pictures

editThe Paramount Pictures Corporation was formed to distribute films made by Famous Players–Lasky and a dozen smaller companies which were pulled into Zukor's corporate giant. The consolidations led to the formation of a nationwide film distribution system.

In 1917, Zukor acquired 50% of Lewis J. Selznick's Select Pictures which led Selznick's publicity to wane. Later, however, Selznick bought out Zukor's share of Select Pictures.[13]

Zukor shed most of his early partners; the Frohman brothers, Hodkinson and Goldwyn were out by 1917.

In 1919, the company bought 135 theaters in the Southern states, making the producing concern the first that guaranteed exhibition of its own product in its own theaters.[4][3] He revolutionized the film industry by organizing production, distribution, and exhibition within a single company.

Zukor believed in employing stars. He signed many of the early ones, including Mary Pickford, Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle, Marguerite Clark, Pauline Frederick, Douglas Fairbanks, Gloria Swanson, Rudolph Valentino, and Wallace Reid. With so many important players, Zukor also pioneered "Block Booking" for Paramount Pictures, which meant that an exhibitor who wanted a particular star's films had to buy a year's worth of other Paramount productions. That system gave Paramount a leading position in the 1920s and 1930s, but led the government to pursue it on antitrust grounds for more than 20 years.

Zukor was the driving force behind Paramount's success. Through the teens and twenties, he also built the Publix Theatres Corporation, a chain of nearly 2000 screens. He also ran two production studios, one in Astoria, New York (now the Kaufman Astoria Studios) and the other in Hollywood, California.

In 1926, Zukor hired independent producer B. P. Schulberg, who had an unerring eye for new talent, to run the new West Coast operations. Lasky and Zukor purchased the Robert Brunton Studios, a 26-acre facility at 5451 Marathon Street,[14] for US$1 million.[4][3] In 1927, Famous Players–Lasky took the name Paramount Famous Lasky Corporation. In 1930, because of the importance of the Publix Theatres, it became the Paramount Publix Corporation.

By then, Zukor was turning out 60 features a year. He made deals to show them all in theaters controlled by Loew's Incorporated, and also continued to add more theaters to his own chain. By 1920, he was in a position to charge what he wished for film rentals. Thus he pioneered the concept, now the accepted practice in the film industry, by which the distributor charges the exhibitor a percentage of box-office receipts.

Zukor, ever the impresario, bought a huge plot of ground at Broadway and 43d Street, over objections of his board of directors, to build the Paramount Theater and office building, a 39-story building that had its grand opening in 1926. He managed to keep stars such as Pola Negri, Gloria Swanson, and most important of all, Mary Pickford, under contract and happy to stay at Paramount. At one point, Pickford told Zukor: "You know, for years I've dreamed of making $20,000 a year before I was 20, and I'll be 20 very soon."

"I could take a hint," Zukor recalled wryly. "She got the $20,000, and before long I was paying her $100,000 a year. Mary was a terrific businessman."[4][3]

Zukor was, primarily, also a businessman. "He did not take the same personal, down-to-the-last-detail interest in the making of his movies that producer-executives such as Samuel Goldwyn and Louis B. Mayer did," wrote The New York Times in Zukor's obituary at the age of 103. He became an early investor in radio, taking a 50 percent interest in the new Columbia Broadcasting System in 1928, but selling it within a few years.

Partner Lasky hung on until 1932, when Paramount nearly collapsed in the Great Depression years. Lasky was blamed for that and tossed out. In the following year, Paramount went into receivership. Ultimately at fault were Zukor's over-expansion and use of overvalued Paramount stock for purchases that made the company file for bankruptcy. A bank-mandated reorganization team kept the company intact, and, miraculously, Zukor was able to return as production chief. On June 4, 1935, John E. Otterson became president.[15] When Barney Balaban was appointed president on July 2, 1936, Zukor was relegated to chairman of the board.[16][17]

He eventually spent most of his time in New York City, but passed the winter months in Hollywood to check on his studio. He retired from Paramount Pictures in 1959 and in 1964, stepped down as chairman and assumed Chairman Emeritus status,[18] a position he held up until his death at the age of 103 in Los Angeles.

Personal life and death

editIn 1897, he married Lottie Kaufman;[4][3] they had two children, Eugene J. Zukor, who became a Paramount executive in 1916, and Mildred Zukor Loew who married Arthur Loew, son of Marcus Loew.[19]

Zukor was a Freemason at Centennial Lodge No. 673, New York.[20][21]

Zukor died from natural causes at his Los Angeles residence at age 103 in June 1976.[4][3][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][excessive citations] He is buried at the Temple Israel Cemetery in Hastings-on-Hudson, New York.

Filmography

editProducer

edit| Year | Title | Director |

|---|---|---|

| 1913 | The Prisoner of Zenda | Hugh Ford |

| 1924 | Peter Pan | Herbert Brenon |

| 1926 | Beau Geste | Herbert Brenon |

| 1927 | Wings | William A. Wellman |

| 1928 | The Docks of New York | Josef von Sternberg |

| The Wedding March | Erich von Stroheim | |

| 1931 | Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde | Rouben Mamoulian |

| 1932 | Shanghai Express | Josef von Sternberg |

| 1936 | The Milky Way | Leo McCarey |

| 1937 | Souls at Sea | Henry Hathaway |

| 1938 | Professor Beware | Elliott Nugent |

Actor

edit| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1929 | Glorifying the American Girl | Himself | Uncredited |

References

edit- ^ Bernstein, Matthew (February 2000). Zukor, Adolph. Oxford University Press.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Obituary Variety (June 16, 1976), p. 76.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Krebs, Albin (June 11, 1976). "Obituary: Adolph Zukor Is Dead at 103; Built Paramount Movie Empire". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 3, 2001. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Krebs, Albin (June 11, 1976). "Adolph Zukor Is Dead at 103; Built Paramount Movie Empire". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 24, 2021. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- ^ a b c Jr, William Wellman (2015). Wild Bill Wellman: Hollywood Rebel. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-101-87028-0.

- ^ Passenger list. "Ancestry. Com". Ancestry.com.

- ^ 1891 passenger list. "Ancestry.com". Ancestry.com.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Gabler, Neal (1988). An empire of their own: how the Jews invented Hollywood (1st ed.). New York: Crown Publishers. p. 16. ISBN 0-517-56808-X.

- ^ Trager, James (1979). The people's chronology: a year-by-year record of human events from prehistory to the present. Austin, Texas, United States: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. p. 823. ISBN 9780030178115.

- ^ Ed Solero, ""Crystal Hall""., Cinema Treasures

- ^ Wu, Tim, Wu, Tim (November 2, 2010). The Master Switch : The Rise and Fall of Information Empires. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. ISBN 9780307594655., New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2010. ISBN 978-0-307-26993-5. Cf. especially Wu, Tim (November 2, 2010). p. 62. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. ISBN 9780307594655. on the film and Sarah Bernhardt. Sections of the book are on the film industry's early days and the then independent film studios such as Paramount.

- ^ Alleman, Richard (2005). New York: The Movie Lover's Guide: The Ultimate Insider Tour of Movie New York - Richard Alleman - Broadway (February 1, 2005). Crown. ISBN 9780767916349. ISBN 0-7679-1634-4

- ^ "Lewis J. Selznick". Variety. January 31, 1933. p. 2.

- ^ "Exterior view of the Paramount Famous Lasky Corporation Studios at 5451 Marathon Street in Hollywood". calisphere. 1930. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ "PARAMOUNT BOARD ELECTS OTTERSON; Head of the Electric Research Products Made President of New Company". The New York Times. New York City. June 5, 1935. p. 29. Retrieved January 9, 2022.

- ^ "FINANCIAL .,, , . e 'rm nrk illr . = . . FINANCIAL BALABAN, ZUKOR HEAD PARAMOUNT; Former Elected President of Pictures Corporation; Latter Retained as Chairman. KENNEDY FINISHES STUDY Report Said to Show Theatres' Profit Offset by Results of Film Production Division". The New York Times. New York City. July 3, 1936. p. 25. Retrieved January 9, 2022.

- ^ Regev, Ronny (2018). Working in Hollywood: How the Studio System Turned Creativity into Labor. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. p. 38. ISBN 9781469637068. Retrieved January 9, 2022.

- ^ "Personalities: Jun. 12, 1964". Time. June 12, 1964. Retrieved September 14, 2019.

- ^ Ingham, John N. (1983). Biographical Dictionary of American Business Leaders, Volume 4. Greenwood. p. 1702. ISBN 978-0313239106.

- ^ "10,000 Famous Freemasons By William R. Denslow - Volume 1 "A-D"". www.phoenixmasonry.org. Retrieved March 17, 2023.

- ^ Royal Arch Mason Magazine, Spring, 1981, p. 271

- ^ "Famed moviemaker Adolph Zukor dies". The San Bernardino Sun. Los Angeles. AP. June 11, 1976. p. 3. Retrieved December 24, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Special Report Adolph Zukor-a Personal Remembrance". June 17, 1976.

- ^ "Adolph Zukor | American motion-picture producer". April 5, 2023.

- ^ "1873: The Original Movie Mogul, Adolph Zukor, is Born". Haaretz.

- ^ "Adolph Zukor | Encyclopedia.com".

- ^ "Reference at www.thejc.com".

- ^ "Adolph Zukor".

Further reading

edit- Adolph Zukor, The Public Is Never Wrong: My 50 Years in the Picture Industry (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1953)

- David Balaban, The Chicago Movie Palaces of Balaban and Katz (Arcadia Publishing, 2006)

- Neal Gabler, An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood (New York: Anchor Books, 1989)

- Will Irwin, The House That Shadows Built (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, Doran, 1928)