Ayida-Weddo, also known as Ayida, Agida, Ayida-Wedo, Aido Quedo, Aido Wedo, Aida Wedo, and Aido Hwedo, is a powerful loa spirit in Vodou, revered in regions across Africa and the Caribbean, namely in Benin, Suriname and Haiti.[1] Known as the "Rainbow Serpent", Ayida-Weddo is the loa of fertility, rainbows, wind, water, fire, wealth,[2] thunder,[3] and snakes.[4][5][6] Alongside Damballa, Ayida-Weddo is regarded among the most ancient and significant loa. Considered in many sources as the female half of Damballa's twin spirit, the names Da Ayida Hwedo, Dan Ayida Hwedo, and Dan Aida Wedo have also been used to refer to her.[7] Thought to have existed before the Earth, Ayida-Weddo assisted the creator goddess Mawu-Lisa in the formation of the world, and is responsible for holding together the Earth and heavens. Ayida-Weddo bestows love and well-being upon her followers, teaching fluidity and the connection between body and spirit.[8][4]

| Ayida-Weddo | |

|---|---|

| Rainbow Serpent | |

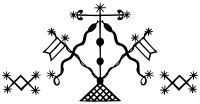

Veve of Ayida-Weddo and Damballa, always depicted together. | |

| Venerated in | Vodou, Folk Catholicism |

| Attributes | rainbow, blue, white paquet congo, ouroboros |

| Patronage | fertility, rainbows, wind, water, fire, wealth, thunder, snakes |

Family

editAyida-Weddo is a member of the Rada family of loa, associated with protection, benevolence, and love.[9] In many stories, she is married to Damballa. As his inseparable companion, she shares him with his concubine, Erzulie Freda.[10] In others, she is one with Damballa: a single entity sharing a dual spirit. As his female aspect, together they represent dynamism, life, creation, and the intertwined harmony of male and female, earth and heaven, and body and spirit.[2][7][11][4][12]

Symbols and offerings

editAyida-Weddo is symbolized by the rainbow, snake, thunderbolt, and white paquet congo.[6] When represented in art, she is often depicted as a serpent consuming its own tail.[2][13] In veves, she is invariably portrayed alongside Damballa as one of two dancing or intertwined serpents. White, as the purest color, represents her in ceremony. When Ayida-Weddo appears in ritual, she dons white cloth and a jeweled headdress, and embodies the serpent by slithering upon the ground.[5][14] Matching her sacred color, appropriate offerings to her include white chickens, white eggs, rice, milk, as well as other white offerings decorated in rainbow colors.[6][8] Her favorite plant is cotton.[15]

Form and function

editThe Fon people of Benin believe the rainbow serpent Ayida-Weddo was a servant of Mawu-Lisa and existed before the Earth was made. As Mawu-Lisa created the world, the serpent carried the goddess in its mouth as she shaped the Earth with her creations. As they went across the land, the rainbow serpent's body left behind the canyons, rivers, valleys, and mountains.[16][17] The rainbow serpent had a twin personality whose red half was male, and whose blue half was female.[18][19] Together, they held up the Earth and the heavens. The female half was said to arc thunderbolts and rainbows across the sky with its body, and lived among the clouds, trees, springs, and rivers.[20] Asked by Mawu-Lisa to help support the weight of her creations on the Earth, the rainbow serpent's male half coiled its body underneath the world to prevent its collapse. As it writhes from exertion under the world's weight, the serpent causes earthquakes in the land.[18][13][21] When it runs out of the iron that sates its hunger, it is said the serpent will devour its tail, finally causing the heavy Earth to sink into the abyss. In some stories, Ayida-Weddo descends from the heavens with Adanhu and Yewa, the first humans created by Mawu.[22]

"In the beginning there was a vast serpent, whose body formed seven thousand coils beneath the earth, protecting it from descent into the abysmal sea. Then the titanic snake began to move and heave its massive form from the earth to envelop the sky. It scattered stars in the firmament and wound its taught flesh down the mountains to create riverbeds. It shot thunderbolts to the earth to create the sacred thunderstones. From its deepest core it released the sacred waters to fill the earth with life. As the first rains fell, a rainbow encompassed the sky and Danbala took her, Ayida Wedo, as his wife. The spiritual nectar that they created reproduces through all men and women as milk and semen. The serpent and the rainbow taught humankind the link between blood and life, between menstruation and birth, and the ultimate Vodou sacrament of blood sacrifice."[20]

In Haiti, Ayida-Weddo is said to have crossed the ocean with her husband Damballa to take the ancient knowledge and traditions of Vodou from Africa to the Caribbean. As Damballa slithered under the ocean, Ayida-Weddo flew across the sky in the form of the rainbow until the two loa reunited in Haiti, bringing Vodou to the Americas.[23]

Ayida-Weddo is syncretized in Haitian Vodou with the Catholic figure of Our Lady of Immaculate Conception for her association with serpents and rainbow-colored cherubs.[15][24] Ayida-Weddo's days of service lie on Monday and Tuesday, and she is honored on December 8 with festivals for her blessings.[23] Through prayer and ritual, she grants peace, love, prosperity, joy, and understanding to her devotees.[25][8]

In West African mythology, Ayida-Weddo is often equated to the Yoruba rainbow serpent Oshumare, with whom she shares many aspects.[26][16][27]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Teish, Luisah (1985). Jambalaya. Harper Sanfrancisco. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-06-250859-1. OCLC 1261277604.

- ^ a b c Lawal, Babatunde (2008). "Èjìwàpò". African Arts. 41 (1): 27. doi:10.1162/afar.2008.41.1.24. ISSN 0001-9933. S2CID 57564389.

- ^ van der Sluijs, Marinus Anthony; Peratt, Anthony L. (2009). "The Ourobóros as an Auroral Phenomenon". Journal of Folklore Research. 46 (1): 15. doi:10.2979/jfr.2009.46.1.3. ISSN 0737-7037. S2CID 162226473.

- ^ a b c Auset, Brandi (2009). The Goddess Guide. Llewellyn Publications. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-7387-1551-3. OCLC 286420995.

- ^ a b Monaghan, Patricia (2014). Encyclopedia of Goddesses and Heroines. New World Library. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-60868-218-8. OCLC 969000530.

- ^ a b c Owusu, Heike (2002). Voodoo Rituals. Sterling. p. 43. ISBN 1-4027-0035-0. OCLC 52194154.

- ^ a b Alcide Saint-Lot, Marie-Jose (2003). Vodou, a Sacred Theatre: The African Heritage in Haiti. Educa Vision. p. 150. ISBN 1-58432-177-6. OCLC 1130907883.

- ^ a b c Dorsey, Lilith (2005). Voodoo and Afro-Caribbean Paganism. Citadel Press. p. 36. ISBN 0-8065-2714-5. OCLC 62595057.

- ^ The Voodoo Encyclopedia: Magic, Ritual, and Religion. Jeffrey E. Anderson. ABC-CLIO. 2015. p. 167. ISBN 978-1-61069-208-3. OCLC 900016740.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Gordon, Leah (1985). The Book of Vodou. Barron's Educational Series. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-7641-5249-8. OCLC 44854654.

- ^ Coleman, Will (2000). Tribal Talk: Black Theology, Hermeneutics, and African/American Ways of "Telling the Story". Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 13. ISBN 0-271-01944-1. OCLC 40631697.

- ^ Bellegarde-Smith, Patrick; Michel, Claudine (2013). "Danbala/Ayida as Cosmic Prism". Journal of Africana Religions. 1 (4): 458–487. doi:10.5325/jafrireli.1.4.0458. ISSN 2165-5405. S2CID 142805771.

- ^ a b Hazel, Robert (2019). Snakes, People, and Spirits, Volume One: Traditional Eastern Africa in Its Broader Context. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 234. ISBN 978-1-5275-4292-1. OCLC 1132394622.

- ^ Coulter, Charles Russell; Turner, Patricia (4 July 2013). Encyclopedia of Ancient Deities. Routledge. p. 141. ISBN 978-1-135-96397-2.

- ^ a b Gordon, Leah (1985). The Book of Vodou. Barron's Educational Series. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-0-7641-5249-8.

- ^ a b Washington, Teresa N. (2005). Our Mothers, Our Powers, Our Texts: Manifestations of Ajé in Africana Literature. Indiana University Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-253-00319-5. OCLC 646474714.

- ^ Rose, Carol (2001). Giants, Monsters, and Dragons: An Encyclopedia of Folklore, Legend, and Myth. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 306. ISBN 0-393-32211-4. OCLC 48798119.

- ^ a b Coleman, Will (2000). Tribal Talk: Black Theology, Hermeneutics, and African/American Ways of "Telling the Story". Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 12. ISBN 0-271-01944-1. OCLC 40631697.

- ^ Wilkinson, Philip (1998). Illustrated Dictionary of Mythology. Dorling Kindersley. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-7894-3413-5.

- ^ a b Gordon, Leah (1985). The Book of Vodou. Barron's Educational Series. p. 60. ISBN 0-7641-5249-1. OCLC 44854654.

- ^ Rose, Carol (2001). Giants, Monsters, and Dragons: An Encyclopedia of Folklore Legend and Myth. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 9. ISBN 0-393-32211-4.

- ^ Philip, Neil (2007). Myths & Legends Explained. DK Publishing. pp. 88–89. ISBN 978-0-7566-2871-0. OCLC 148756966.

- ^ a b Dorsey, Lilith (2005). Voodoo and Afro-Caribbean Paganism. Citadel Press. p. 55. ISBN 0-8065-2714-5.

- ^ The Voodoo Encyclopedia: Magic, Ritual, and Religion. Jeffrey E. Anderson. ABC-CLIO. 2015. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-61069-208-3. OCLC 900016740.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Conner, Randy P.; Sparks, David Hatfield (2004). Queering Creole Spiritual Traditions: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Participation in African-Inspired Traditions in the Americas. Harrington Park Press. p. 57. ISBN 1-56023-350-8.

- ^ Hazel, Robert (2019). Snakes, People, and Spirits, Volume One: Traditional Eastern Africa in Its Broader Context. Newcastle upon Tyne. p. 238. ISBN 978-1-5275-4292-1. OCLC 1132394622.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Rose, Carol (2001). Giants, Monsters, and Dragons: An Encyclopedia of Folklore, Legend, and Myth. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 282. ISBN 0-393-32211-4. OCLC 48798119.