Italian protectorate of Albania (1939–1943)

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Italian. (March 2021) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

The Italian protectorate of Albania (Italian:Protettorato italiano dell'Albania),also known as Italian Albania, the Kingdom of Albania or Greater Albania,[3][4] existed as a puppet state and protectorate of Fascist Italy. It was practically a union between Italy and Albania, officially led by Italian King Victor Emmanuel III and his government: Albania was led by Italian governors, after being militarily occupied by Italy, from 1939 until 1943. During this time, Albania ceased to exist as an independent country and became an autonomous part of the Italian Empire. Officials intended to make Albania part of a Greater Italy by assimilating Albanians as Italians and colonizing Albania with Italian settlers from the Italian Peninsula to transform it gradually into an Italian land.[5]

Kingdom of Albania | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1939–1943 | |||||||||||||

| Motto: FERT (Motto for the House of Savoy) | |||||||||||||

| Anthem: Himni i Flamurit ("Hymn to the Flag") | |||||||||||||

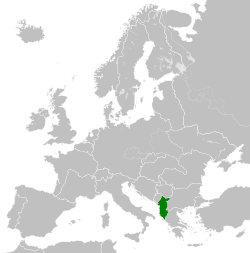

The Italian protectorate of Albania in 1942 | |||||||||||||

| Status | In personal union with Fascist Italy (de jure) part of the Italian Empire (de facto) | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Tirana | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Albanian Italian | ||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Albanian | ||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||

• 1939–1943 | Victor Emmanuel III | ||||||||||||

| Lieutenant-General of the King | |||||||||||||

• 1939–1943 | Francesco Jacomoni | ||||||||||||

• 1943 | Alberto Pariani | ||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||||

• 1939–1941 | Shefqet Vërlaci | ||||||||||||

• 1941–1943 | Mustafa Merlika-Kruja | ||||||||||||

• 1943 | Ekrem Libohova | ||||||||||||

• 1943 | Maliq Bushati | ||||||||||||

• 1943 | Ekrem Libohova | ||||||||||||

| Legislature | Parliament | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

| 12 April 1939 | |||||||||||||

| 10 July 1941 | |||||||||||||

| 8 September 1943 | |||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

| 1939[2] | 28,748 km2 (11,100 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| 1940-1943 | 52,667 km2 (20,335 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||

• 1939[2] | 1,063,893 | ||||||||||||

• 1940-1943 | 1,701,463 | ||||||||||||

| Currency | Franga (1939–1941) Italian lira (1941–1943) | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

In the Treaty of London during World War I, the Triple Entente had promised central and southern Albania to Italy as a reward for fighting against the Central Powers.[6] In June 1917, after Italian soldiers seized control of substantial areas of Albania, Italy formally declared a protectorate over central and southern Albania; however this was overturned in September 1920 when Italy was pressured to withdraw its army.[6] Italy was enraged with the minimal gains that it received from peace negotiations, which it regarded as having violated the Treaty of London. Italian Fascists claimed that Albanians were ethnically linked to Italians through association with the prehistoric populations, and that the major influence exerted by the Roman and Venetian empires over Albania gave Italy the right to possess it.[7] In addition, several hundred thousand ethnic Albanians had already been absorbed into southern Italy, which was used to justify annexation as a measure that would unite all Albanians into one state.[8] Italy supported Albanian irredentism, directed against the predominantly Albanian-populated Kosovo in Yugoslavia, but also against Epirus in Greece, particularly the border area of Chameria, inhabited by the Cham Albanian minority.[9]

History

editPre-invasion: Italy's influence and aims in Albania

editPrior to direct intervention in World War I, the Kingdom of Italy occupied the port of Vlorë in Albania in December 1914.[6] Upon entering the war, Italy spread its occupation to region of southern Albania beginning in the autumn 1916.[6] Italian forces in 1916 recruited Albanian irregulars to serve alongside them.[6] Italy with permission of the Allied command, occupied Northern Epirus on 23 August 1916, forcing the Greek Army to withdraw its occupation forces from there.[6] In June 1917, Italy proclaimed central and southern Albania as a protectorate of Italy while Northern Albania was allocated to the states of Serbia and Montenegro.[6] By 31 October 1918, French and Italian forces expelled the Austro-Hungarian Army from Albania.[6] After World War I ended, Italy withdrew its military forces on 2 September 1920 from Albania as a result of foreign pressure and defeat in the Vlora War.[6]

The Italian Fascist regime had politically and economically penetrated and dominated Albania during Zog's rule and was planning for annexation of Albania years prior to the event.[10] Albania came under strong Italian influence after the signing of the Treaties of Tirana of 1926 and 1927.[11][12][13] Under Zog, Albania's economy was dependent on multiple financial loans given from Italy since 1931.[14]

In August 1933, Mussolini placed stringent demands on Zog in exchange for Italy's continued support of Albania, including demands that all new appointments to leading positions in the Albanian government had to have received an "Italian education"; that an Italian expert was in the future to be in all Albanian government ministries; that Italy would take control of Albania's military – including its fortifications; that British officers that were training Albania's gendarmerie be replaced by Italian officers; and that Albania must annul all of its existing commercial treaties with other countries and make no new agreements without the approval of the Italian government; and that Albania sign a commercial convention that would make Italy Albania's "most favoured country" in trade.[15] In 1934 when Albania did not deliver its scheduled payment of one loan to Italy, Italian warships arrived off the coast of Albania to intimidate Albania to submit to Italian goals in the region. However, the British opposed Italy's actions and under pressure, Italy backed down and claimed that the naval exercise was merely a "friendly visit".[14]

On 25 August 1937, Italian foreign minister Count Ciano wrote in his diary of Italy's relations with Albania in the following: "We must create stable centres of Italian influence there. Who knows what the future may have in store? We must be ready to seize opportunities which will present themselves. We are not going to withdraw this time, as we did in 1920. In the south [of Italy] we have absorbed several hundred thousand Albanians. Why shouldn't the same thing happen on the other side of the entrance to the Adriatic.".[8] On 26 March 1938, Ciano wrote in his diary of annexing Albania like Germany did with Austria shortly prior: "A report from Jacomoni on the situation in Albania. Our penetration is becoming steadily more intense and more organic. The programme which I traced after my visit is being carried out without a hitch. I am wondering whether the general situation – particularly the Anschluss [with Austria] – does not permit us to take a step forward towards the more complete domination of this country, which will be ours." and days later on 4 April of that year wrote "We must gradually underline the protectorate element of our relations with Albania".[16]

Invasion and the establishment of the Italian regime

edit"The Kosovars are 850,000 Albanians, strong of body, firm in spirit, and enthusiastic about the idea of a Union with their Homeland. Apparently, the Serbians are terrified of them. Today one must ... chloroform the Yugoslavians. But later on one must adopt a politics of deep interest in Kosovo. This will help to keep alive in the Balkans an irredentist problem which will polarize the attention of the Albanians themselves and be a knife at the back of Yugoslavia..."

Galeazzo Ciano, Mussolini's son-in-law, the Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs, speaking of Albanian claims to Kosovo as valuable to Italy's objectives.[17]

In spite of Albania's long-standing alliance with Italy, on 7 April 1939 Italian troops invaded Albania,[18] five months before the start of the Second World War. The Albanian armed resistance proved ineffective against the Italians and, after a short defense, the country was occupied. On 9 April 1939 the Albanian king, Zog I fled to Greece.[19] Although Albania had been under strong Italian influence since 1927,[13][20][21] Italy's political leader, Benito Mussolini wanted direct control over the country to increase his and Italy's prestige, provide a response to Germany's annexation of Austria and occupation of Czechoslovakia, and to have firm control over Albania to station large forces of the Italian military for future operations involving Yugoslavia and Greece.

Albania became an Italian protectorate subordinated to Italian interests,[22] along the lines of the German Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. Victor Emmanuel III was proclaimed king of Albania, creating a personal union with Italy; he was represented in Tirana by a viceroy. A customs union was created, and Rome took over Albanian foreign policy. Although officially under Italian rule, the Albanians controlled the region and were encouraged to open Albanian language schools, which had been banned by the Yugoslav government. The Italians also gave the inhabitants Albanian citizenship and allowed them to fly the Albanian Flag. The Albanian armed forces were subsumed into the Italian military, Italian advisers were placed inside all levels of the Albanian administration, and the country was fascisticized with the establishment of an Albanian Fascist Party and its attendant organizations, modelled after the Italian prototype. The Albanian Fascist Party was a branch of the National Fascist Party of Italy, members of the Albanian Fascist Party took an oath to obey the orders of the Duce of Fascism, Mussolini.[23] Italian citizens began to settle in Albania as colonists and to own land so that they could gradually transform it into Italian soil.[5] The italianization of Albania was one of Mussolini's plans.[24]

While Victor Emmanuel ruled as king, Shefqet Vërlaci served as the prime minister. Vërlaci controlled the day-to-day activities of the Italian protectorate. On 3 December 1941, Shefqet Vërlaci was replaced as prime minister by Mustafa Merlika-Kruja.[25] The country's natural resources too came under direct control of Italy. All petroleum resources in Albania went through Agip, Italy's state petroleum company.[26]

Albania was important culturally and historically to the nationalist aims of the Italian Fascists, as the territory of Albania had long been part of the Roman Empire, even prior to the annexation of northern Italy by the Romans. Later, during the High Middle Ages some coastal areas (like Durazzo) had been influenced and owned by Italian powers, chiefly the Kingdom of Naples and the Republic of Venice for many years (cf. Albania Veneta). The Italian Fascist regime legitimized its claim to Albania through studies proclaiming the racial affinity of Albanians and Italians, especially as opposed to the Slavic Yugoslavs.[27] Italian Fascists claimed that Albanians were linked through ethnic heritage to Italians, not to Slavs, and that the major influence exhibited by the Roman and Venetian empires over Albania justified Italy's right to possess it.[28]: 106

Italy also attempted to legitimize and win public support for its rule over Albania by supporting Albanian irredentism, directed against the predominantly Albanian-populated Kosovo in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and Epirus in Greece, particularly the border area of Chameria, inhabited by the Cham Albanian minority.[9] Thus an author the Fascist Italian publication named Geopolitica claimed that the population of the Epirus-Acarnania region of Greece belonged to Albania due to it being racially Dinaric, and formed a 'single geographic system' with the Adriatic zone.[28]: 106 Despite the efforts of the Italian vicegerent, Francesco Jacomoni, to stir up insurrections and create a fifth column, and the favourable reports he sent to the Italian foreign minister Count Ciano, events proved that there was little enthusiasm among the Albanians themselves: after the Italian invasion of Greece, most Albanians either deserted or defected.[29]

Albania at war

editStrategically, control of Albania gave Italy an important beachhead in the Balkans: not only did it complete Italian control of the Strait of Otranto and the entrance to the Adriatic Sea, it could be used to invade either Yugoslavia (in tandem with another thrust via Venezia Giulia) or Greece.[20]

In 1939, Count Ciano spoke of Albanian irredentist claims to Kosovo as valuable to Italy's objectives, saying:

The Kosovars [are] 850,000 Albanians, strong of body, firm in spirit, and enthusiastic about the idea of a Union with their Homeland. Apparently, the Serbians are terrified of them. Today one must…chloroform the Yugoslavians. But later on one must adopt a politics of deep interest in Kosovo. This will help to keep alive in the Balkans an irredentist problem which will polarize the attention of the Albanians themselves and be a knife at the back of Yugoslavia.[17]

— Galeazzo Ciano, 1939

The Corporative Council of the Albanian Fascist Party, a quasi-statal organization, issued a directive on 16 June 1940, shortly after Italy's declarations of war against Britain and France, that stated that "The Kingdom of Albania considers itself at war with all nations against which Italy is at war – at present or in the future."[30]

In October 1940, during the Greco-Italian War, Albania served as a staging-area for Italian dictator Benito Mussolini's unsuccessful invasion of Greece. Mussolini planned to invade Greece and other countries like Yugoslavia in the area to give Italy territorial control of most of the Mediterranean Sea coastline, as part of the Fascists' objective of creating the objective of Mare Nostrum ("Our Sea") in which Italy would dominate the Mediterranean. But the Albanian army under the command of colonel (later general) Prenk Pervizi[31] abandoned the Italians in combat, causing a major unraveling of their lines. The Albanian army believed to be the cause of the betrayal was removed from the front. The Colonel Pervizi and his staff of officials was isolated in the mountains of Puka and Shkodra to the North.[32] This was the first action of revolt against the Italian occupation.

But, soon after the Italian invasion, the Greeks counter-attacked and a sizable portion of Albania was in Greek hands (including the cities of Gjirokastër and Korçë). In April 1941, Greece capitulated after an overwhelming German invasion. All of Albania returned to Italian control, which was also extended to most of Greece, which was jointly occupied by Italy, Germany and Bulgaria. Italian plans however to annex Chameria to Albania were shelved because the Italians found the region to have been almost completely Greek and also due to the strong opposition of the region's Greek population.[28]: 108 [33] The Germans also opposed such a move for the same reasons,[34] and also because they were opposed to any territorial reduction of the Hellenic state.[28]: 108

After the fall of Yugoslavia and Greece in April 1941, the Italian government began negotiations with Germany, Bulgaria, and the newly established client state, the Independent State of Croatia, on defining their borders. In April Mussolini called for the borders of Albania to be expanded – including annexing Montenegro into Albania that would have an autonomous government within Albania, and expanding Albania's border eastwards, though not as far as the Vardar river as some had proposed – citing that Ohrid should be left to the Slavic Macedonians, regardless of whether Vardar Macedonia would become an independent state or be annexed by Bulgaria.[28]: 79 However the Italian government changed its positions on the border throughout April, later supporting the annexation of Ohrid while giving the territory lying directly outside of Ohrid (including the sacred birthplace of Saint Clement) to the Slavic Macedonians.[28]: 79 After a period of negotiations Italy's new Balkan borders – including Albania's new borders, were declared by royal decree on 7 June 1941.[28]: 79

After the Italian capitulation in September 1943, the country was occupied by the Germans until the end of the war.

Persecution

editAround 200 Albanian Jews and 400 Jewish refugees resided in Albania proper prior to World War II. Albanian Jews were generally protected but faced some restrictions. Foreign Jews were placed into concentration camps. The Jewish population of Kosovo fared comparatively worse as Italian authorities turned them over to the Germans where they were murdered or sent to camps in Albania. Others were taken to Albanian cities where the local population protected them.[35] See The Holocaust in Albania.

Kosovar Albanians collaborated with the Axis powers who promised them a Greater Albania.[36] This was seen as a better alternative to the repressive measures instilled by Serbian politicians during the interwar period.[37] In June 1942 Prime Minister Mustafa Kruja stated that Serbs would be sent to concentration camps or killed.[38] Between 70,000 and 100,000 Kosovar Serbs were transferred to concentration camps in Pristina and Mitrovica or expelled to Serbia proper, in order to Albanianize the province.[37] During the occupation, the population was subject to forced labour, torture, destruction of private property, destruction and damaging of cultural and historical buildings and graveyards.[39] The expulsion of Serbs proved problematic, as they had performed important functions in the region, and been running most of the businesses, mills, tanneries, and public utilities, and been responsible for most of the useful agricultural production.[40] According to Serbian sources, it is estimated that the Vulnetari and other paramilitaries murdered up to 10,000 Serbs and Montenegrins in Kosovo.[41][42]

Economy

editUpon the occupation of Albania and installation of a new government, the economies of Albania and Italy were connected through a customs union that resulted in the removal of most trade restrictions.[23] Through a tariff union, the Italian tariff system was put in place in Albania.[23] Due to the expected economic losses in Albania from the alteration in tariff policy, the Italian government provided Albania 15 million Albanian leks each year in compensation.[23] Italian customs laws were to apply in Albania and only Italy alone could conclude treaties with third parties.[23] Italian capital was allowed to dominate the Albanian economy.[23] As a result, Italian companies were allowed to hold monopolies in the exploitation of Albanian natural resources.[23]

In 1944, the number of companies and industrial enterprises reached 430, from just 244 in 1938 and only 71 such in 1922. The degree of concentration of workers in industrial production in 1938 doubled compared with 1928. At this time, Albania's economy had trade relations with 21 countries, but most developed were first to Italy and then to Yugoslavia, France, Germany, Greece, etc.

The country entered capitalist economic development much later than other European countries. Despite the presence of some foreign (mainly Italian) investment, Albania had made little move towards industrial development at the onset of World War II. Agriculture, which employed over 87% of the workforce, was the main sector of the economy and contributed 92.4% of the national income, with main outputs being wheat, maize and rye. Agriculture used primitive tools such as wood ploughs, whilst fertilisers were hardly known at all, and drainage poor. The level of productivity and level of organization and mechanization of agriculture in this period were very low.

Administrative division

editThe Italians adopted the existing Albanian system of prefectures (Italian: prefetture). In line with the administrative structure of the rest of Italy these were also called provinces (Italian: provincia). However, unlike Italy the Albanian sub-prefecture (Italian: sotto prefetture) was retained. There were initially 10 prefectures.[43][44] Under this was 30 sub-prefectures and 23 municipalities (Italian: municipalità).[45] Each Prefecture was run by a Prefect located in the city of the same name. In 1941, following the dismemberment of Yugoslavia, three new Prefectures were added. Kossovo, Metohija and Debar, with 5 sub-prefectures.[46] Also Ulcinj was added to Scutari prefecture as sub-prefecture.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Symbols of the Albanian Kingdom (1939–1943)". September 2022.

- ^ a b Soldaten-Atlas (Tornisterschrift des Oberkommandos der Wehrmacht, Heft 39). Leipzig: Bibliographisches Institut. 1941. p. 32.

- ^ Micheletta, Luca (2007), "Questioni storiche: Italy, Greater Albania and Kosovo 1939–1943", Nuova Rivista Storica, 2/2013, Universita degli studi di Roma La Sapienza: 521–542

- ^ Papa Pandelejmoni, Enriketa (2012), Doing politics in Albania doing World War II: The case of Mustafa Merlika Kruja fascist collaboration, Založba ZRC, ZRC SAZU, pp. 67–83, ISBN 978-9612544010

- ^ a b Lemkin, Raphael; Power, Samantha (2008), Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd., pp. 99–107, ISBN 978-1584779018

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Nigel Thomas. Armies in the Balkans 1914–18. Osprey Publishing, 2001. p. 17.

- ^ Kane, Robert B. (2014). "Albania, Italian occupation of, 1939". In Hall, Richard C. (ed.). War in the Balkans: An Encyclopedic History from the Fall of the Ottoman Empire to the Breakup of Yugoslavia. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9798216163312.

- ^ a b Pearson 2007, p. 389.

- ^ a b Fischer, Bernd Jürgen (1999), Albania at War, 1939–1945, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, pp. 70–73, ISBN 978-1850655312

- ^ Pearson 2007, p. 378, 389.

- ^ Aristotle A. Kallis. Fascist ideology: territory and expansionism in Italy and Germany, 1922–1945. London: Routledge, 2000. p. 132.

- ^ Zara S. Steiner. The lights that failed: European international history, 1919–1933. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005. p. 499.

- ^ a b Roy Palmer Domenico. Remaking Italy in the twentieth century. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2002. p. 74.

- ^ a b Pearson 2007, p. 378.

- ^ Pearson 2007, p. 351.

- ^ Pearson 2007, p. 396.

- ^ a b Zolo, Danilo (2002). Invoking Humanity: War, Law, and Global Order. London; New York: Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 24. ISBN 9780826456564.

- ^ Keegan, John; Churchill, Winston (1986). The Second World War (Six Volume Boxed Set). Boston: Mariner Books. p. 314. ISBN 039541685X.

- ^ Zabecki, David T. (1999). World War II in Europe: an encyclopedia. New York: Garland Pub. p. 1353. ISBN 0824070291.

- ^ a b Kallis, Aristotle A. (2000), Fascist ideology: territory and expansionism in Italy and Germany, 1922–1945, Routledge, p. 132, ISBN 978-0415216128

- ^ Steiner, Zara S. (2005), The lights that failed: European international history, 1919–1933, Oxford University Press, p. 499, ISBN 978-0198221142

- ^ "Zog I | king of Albania". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g Raphaël Lemkin. Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. Slark, New Jersey: The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd., 2005. p. 102.

- ^ Cullhaj, Florian (2016). Democratization from within: Political Culture and the Consolidation of Democracy in Post-Communist Albania. Edizioni Nuova Cultura. p. 42. ISBN 978-8868128258.

- ^ Owen Pearson (2006). Albania in the Twentieth Century, A History : Volume II: Albania in Occupation and War, 1939–45. London: I. B. Tauris. p. 167. ISBN 1845111044.

- ^ Pearson, Owen (2006). Albania in Occupation and War: From Fascism to Communism 1940–1945. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1845111045.

- ^ Kallis, Aristotle A. (2000), Fascist ideology: territory and expansionism in Italy and Germany, 1922–1945, Routledge, pp. 132–133, ISBN 978-0415216128

- ^ a b c d e f g Rodogno, Davide (2006). Fascism's European empire: Italian occupation during the Second World War. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84515-1.

- ^ Fischer, Bernd Jürgen (1999), Albania at War, 1939–1945, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, pp. 73–79, ISBN 978-1850655312

- ^ Angelo Piero Sereni, "The Legal Status of Albania", The American Political Science Review 35 2 (1941): 317.

- ^ Pieter Hidri, General Prenk Pervizi, Tirana, Toena, 2002.[ISBN missing]

- ^ Julian Amery, The sons of the Eagle, London, 1946, s. 302–306

- ^ Martucci, Donato (2014). ""Le terre albanesi redente". La Ciameria tra irredentismo albanese e propaganda fascista" (PDF). Palaver. 3 (2). University of Salento: 168 – via CORE.

E così ovunque si recasse nella regione. Persino in Albania, a Delvino e Saranda, non erano convinti che fosse opportuno ingrandire l'Albania verso sud, con l'annessione di territori abitati nella quasi totalità da greci.

- ^ Manta, Eleftheria K. (2009). "The Çams of Albania and the Greek State (1923–1945)". Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs. 29 (4): 523–535. doi:10.1080/13602000903411424. ISSN 1360-2004.

- ^ Bazyler, Michael J.; Boyd, Kathryn Lee; Nelson, Kristen L. (2019). Searching for Justice After the Holocaust: Fulfilling the Terezin Declaration and Immovable Property Restitution. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0190923068.

- ^ Denitch, Bogdan Denis (1996). Ethnic Nationalism: The Tragic Death of Yugoslavia. University of Minnesota Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0816629473.

- ^ a b Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-building and Legitimation, 1918–2005. Indiana University Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0253346568.

- ^ Pinos, Jaume Castan (2018). Kosovo and the Collateral Effects of Humanitarian Intervention. Routledge. p. 33. ISBN 978-1351374767.

- ^ Antonijević, Nenad (2009). Албански злочини над Србима на Косову и Метохији у Другом светском рату, документа (PDF). Muzej žrtava genocida. p. 9. ISBN 978-8690632992.

- ^ Fischer, Bernd Jürgen (1999). Albania at War, 1939–1945. Hurst. p. 238. ISBN 978-1850655312.

- ^ Bataković, Dušan T. (1998). Kosovo: la spirale de la haine: les faits, les acteurs, l'histoire (in French). L'Ahe D'Homme. p. 43. ISBN 978-2825111321. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

On estime que la milice volontaire albanaise Vulnetari (env. 5 000 hommes), assistee per diverses formations paramilitaires, assassina en quatre ans quelque 10 000 Serbs.

- ^ Antonijević, Nenad. Arhivska građa o ljudskim gubicima na Kosovu i Metohiji u Drugome svetskom ratu. p. 479.

Najrealnije procene, na osnovu dostupnih arhivskih izvora, ukazuju da je u toku Drugoga svetskog rata na Kosovu i Metohiji život izgubilo oko 10 hiljada Crnogoraca i Srba, među kojima su većina stradali kao žrtve terora i zločina albanskih kvislinga.

- ^ Great Britain, War Office; Italy OR 5301 (1943)

- ^ Great Britain, War Office; Albania OR 5824 (1943)

- ^ ""Historia e ndarjes administrative nga Ismail Qemali në '92" | Gazeta Panorama". Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ^ Davide Rodogno. Fascism's European empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006, p. 293.

Bibliography

edit- Pearson, Owen (2007). Albania in the Twentieth Century, A History: 3 Volume Set. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 9781845110161.

- Hibbert, Reginald (1991). Albania's National Liberation Struggle: The Bitter Victory. Pinter Publishers. ISBN 9780861871094.