Albertine Randall Wheelan (May 27, 1863 - January 9, 1954) was an American illustrator, cartoonist, and costume designer.

Early life

editAlbertine Randall was born May 27, 1863, in San Francisco, California.[1] A 1921 article in the American Magazine of Art lists San Francisco's Chinatown as a particular influence on her artistic development.[2] In 1887, she married businessman Fairfax Henry Wheelan, with whom she had two children, Edgar Stow Wheelan and Fairfax Randall Wheelan.[3] After her husband's death in 1915, she moved to New York City.[3]

Career

editWheelan signed her work with her married name, Albertine Randall Wheelan.[3] For two decades prior to her move to New York, she was primary costume designer for David Belasco.[3] She designed costumes for Belasco's opera A Grand Army Man in 1904, and for his 1907 production The Rose of the Rancho, as well as for the 1914 operetta Sari by C.S. Cushing, E.P. Heath, and Emmerich Kalman.[4][5]

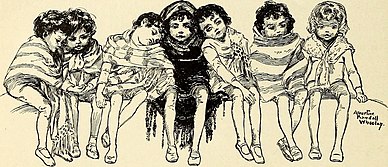

Wheelan also illustrated children's books and magazines, including a number of pieces in St. Nicholas Magazine and Kindergarten Review, as well as The Quarterly Illustrator. [2][6][7] Her illustrations for the children's book A Chinese Child's Day garnered praise in The New York Times in a 1910 piece on children's literature.[8] She is noted in an article in the Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society as the designer of a bookplate for books "Given by the Ladies of the Temple Emanu-El, San Francisco," in 1904.[9]

In the 1920s, Wheelan produced a newspaper comic called In Rabbitboro, originally published in the George Matthew Adams Service bulletin.[10] A 1922 book on humorists listed her among "the principal newspaper comic artists of this country," listing In Rabbitboro as her primary work of note.[11] In Rabbitboro was later retitled The Dumbunnies, and Wheelan patented it as The Dumbunnies in 1927.[12][13]

Wheelan died in Litchfield, CT on January 9, 1954.[14][15]

Exhibitions

editWheelan's work was included in the Woman's Building at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair.[16] In an account of women illustrators' work shown at the Fair, Alice C. Morse wrote that Wheelan "shows great originality, a remarkable sense of the humorous, and a daring handling of the pen. We enjoy hugely her Chinamen, cats, and other amusing creations. They are real beyond a shadow of a doubt, and one is positive that they have done, and will do again, all the ludicrous things that Mrs. Wheelan represents them as doing."[16]

In March 1911, some of Wheelan's bookplates were shown in an exhibition at the Society of Arts and Crafts of Detroit, lent by a member of the California Book-Plate Society.[17]

In March 1935, the Carlyle Gallery exhibited some of Wheelan's drawings of "Spanish, Parisian, and Mallorcan subjects".[18][19] In October 1937, Wheelan's travel sketches were exhibited at the Hudson Park Branch of the New York Public Library.[20]

References

edit- ^ "Albertine Randall". Lambiek Comiclopedia.

- ^ a b Wright, Helen (April 1921). "The Stage Costume Design of Albertine Randall Wheelan". The American Magazine of Art. 12 (4): 124–129. JSTOR 23939507.

- ^ a b c d "Albertine Randall". lambiek.net. Retrieved 2019-03-03.

- ^ "Albertine Randall Wheelan". Playbill. Retrieved 2019-03-03.

- ^ "Albertine Randall Wheelan Theatre Credits, News, Bio and Photos". broadwayworld.com. Retrieved 2019-03-03.

- ^ Lathrop, George Parsons (March 1894). "My Favorite Model". The Quarterly Illustrator. 2 (5): 69–83. JSTOR 25581856.

- ^ Kindergarten Review. 1912.

- ^ Schwed, Hermine (10 April 1910). "CHILDHOOD BOOKS FOR VARIOUS AGES: A Long List of Pretty or Quaint or Improving Stories About Children -- Song Books, Garden Books, and Tales". The New York Times.

- ^ Goodman, Philip (March 1956). "American Jewish Bookplates". Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society. 45 (3): 129–216. JSTOR 43058925.

- ^ "Adams Service Bulletin Lists Many Attractive New Features". The Fourth Estate. October 7, 1922. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- ^ Masson, Thomas Lansing (1922). Our American Humorists. New York City: Moffat, Yard and Company. pp. 427.

in rabbitboro.

- ^ Goulart, Ron (1995). The Funnies: 100 Years of American Comic Strips. Adams Pub. p. 72. ISBN 9781558505391.

- ^ Official Gazette of the United States Patent Office. The United States Patent Office. 1927. p. 721.

- ^ Hughes, Edan Milton (2002). Artists in California, 1786-1940: L-Z. Crocker Art Museum. p. 911. ISBN 9781884038082.

- ^ "Mrs. A. R. Wheelan". The New York Times. 9 January 1954.

- ^ a b Elliott, Maud Howe (1894). Art and Handicraft in the Woman's Building of the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893. Chicago: Rand, McNally. pp. 91–93.

albertine randall.

- ^ Plumb, Helen (May 1911). "Book-Plates: Notes on an Exhibition Held in Detroit". Art and Progress. 2 (7): 189–194. JSTOR 20560374.

- ^ "New York Exhibitions—March". The American Magazine of Art. 28 (3): 190–192. March 1935. JSTOR 23933033.

- ^ Devree, Howard (10 February 1935). "IN THE ART GALLERIES: FROM DAUMIER TO SANTA FE: Contrasting American Artists of Last Century and This -- A Variety of Shows". The New York Times.

- ^ Devree, Howard (24 October 1937). "A REVIEWER'S NOTEBOOK: Brief Comment on Some of the Recently Opened Exhibitions in the Galleries". The New York Times.

External links

editA selection of Wheelan's bookplates on ARTSTOR