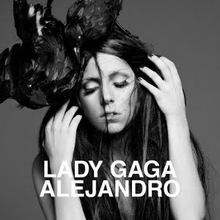

"Alejandro" is a song by American singer Lady Gaga from her third extended play (EP), The Fame Monster (2009)—the reissue of her debut studio album, The Fame (2008). Written and produced by Gaga and RedOne, it was released on April 20, 2010, as the third single from the EP. Interscope Records intended the track "Dance in the Dark" to be the EP's third single after "Alejandro" initially received limited airplay, but Gaga insisted on the latter. A synth-pop track with Europop and Latin pop beats, it opens with a sample from the main melody of Vittorio Monti's "Csárdás". The song was inspired by Gaga's fear of men and is about her bidding farewell to her Latino lovers named Alejandro, Roberto and Fernando.

| "Alejandro" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by Lady Gaga | ||||

| from the EP The Fame Monster | ||||

| Language | English | |||

| Released | April 20, 2010 | |||

| Recorded | 2009 | |||

| Studio | FC Walvisch (Amsterdam) | |||

| Genre | Synth-pop | |||

| Length | 4:34 | |||

| Label |

| |||

| Songwriter(s) | ||||

| Producer(s) |

| |||

| Lady Gaga singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Music video | ||||

| "Alejandro" on YouTube | ||||

Some critics praised the track's catchiness and production while others criticized it as unoriginal, mainly due to the influence from the pop acts ABBA and Ace of Base. Retrospective reviewers ranked the song as one of Gaga's best. Following the album's release, the song charted in the UK and Hungary. Upon its release as a single, "Alejandro" topped the Czech, Finnish, Greek, Mexican, Venezuelan, Polish, Russian and Romanian charts, and reached the top five in the US, Australia, Canada and Sweden. In a 2017 journal, which studied structural patterns in melodies of earworm songs, American Psychological Association called "Alejandro" one of the catchiest in the world.

The accompanying music video, directed by fashion photographer Steven Klein, was inspired by Gaga's admiration of her gay friends and gay love. In the video, she dances with male soldiers in a cabaret, interspersed with scenes of near-naked men holding machine guns and Gaga playing a nun who swallows a rosary. Critics complimented the video's idea and dark nature and compared it with the work of 1980s pop artists. The Catholic League criticized Gaga's use of religious symbols in the video. Retrospective commentators analyzed the video's themes, including BDSM, anti-fascism, sexual violence and religion. Gaga performed the song on the ninth season of American Idol and many of her concert tours and residency shows.

Background and release

editLady Gaga and RedOne wrote and produced "Alejandro"; they also worked on vocal arrangement and background vocals. RedOne solely handled instrumentation, programming and recording, and worked with Eelco Bakker on audio engineering. The song was mixed by Robert Orton and mastered by Gene Grimaldi. Johnny Severin did vocal editing. "Alejandro" was recorded at FC Walvisch Studios in Amsterdam.[1]

Interscope Records planned to release "Dance in the Dark" as the third single from the extended play (EP) The Fame Monster (2009)—the reissue of Gaga's debut studio album, The Fame (2008).[2][3][4] Her own choice, "Alejandro", initially saw poor airplay and was not seen as a viable choice. Following a quarrel between Gaga and her label, "Alejandro" was chosen as the third single. Through her account on Twitter, Gaga remarked on the decision, "Alejandro is on the radio. Fuck it sounds so good, we did it little monsters."[3][4] The single was officially sent to radio on April 20, 2010, in the United States.[5] She told Fuse TV that the inspiration behind "Alejandro" was her "Fear of Men Monster".[6] According to NME, Gaga longs for the affection of her ex-lovers but rejects them, fearing commitment and abandonment.[7]

Music and lyrics

edit"Alejandro" is a synth-pop song with what Billboard describes as a "romping, stomping Euro-pop beat".[8][9] "Alejandro" opens with the main melody from the piece "Csárdás" by Italian composer Vittorio Monti played on violin,[10] as a distressed Gaga states in a Spanish accent: "I know that we are young, and I know that you may love me/But I just can't be with you like this anymore, Alejandro." In a Cambridge University Press-published journal analyzing Gaga's "musical intertexts" on The Fame Monster, authors Lori Burns, Alyssa Woods and Marc Lafrance described her voice during this passage as "compressed and filtered to create a distant but focused effect".[11] Gaga sings the pre-chorus where she describes her relationship as problematic and lets her lover know about making a choice: "You know that I love you, boy/Hot like Mexico, rejoice!/At this point I've got to choose/Nothing to lose."[12] By the song's end, Gaga bids her lovers—Alejandro, Fernando, and Roberto—farewell.[9]

According to the sheet music published at Musicnotes.com by Sony/ATV Music Publishing, the song is set in the time signature of common time, with a moderate tempo of 99 beats per minute. It is composed in the key of B minor with Gaga's vocal range spanning from F♯3 to G4. The song has a basic sequence of Bm–D–F♯m as its chord progression.[13] "Alejandro" is influenced by Ace of Base and ABBA,[9][14] particularly the latter's 1975 song "Fernando".[14][15] Burns, Woods and Lafrance believed by referencing "Fernando", which was popular within the gay community, Gaga identifies as an advocate for the rights of marginalized minorities.[12] This is solidified by the influence of Latin pop songs in the chorus, especially Shakira's "Whenever, Wherever" and Madonna's "La Isla Bonita", which had commercial success in the LGBTQ community.[16] Comparing the song with Ace of Base's "Don't Turn Around"—which tells the story of a woman left by her male lover—Burns, Woods and Lafrance added that "Alejandro" switches this concept where Gaga initiates the break-up.[17] As such, the song shows Gaga's commitment to feminism and "liberat[ing]" performance art.[18] Eve Barlow of Vulture praised Gaga's outspoken sex-positive feminism in the song, exemplified by the lyrics "don't want to kiss, don't want to touch/Just smoke my cigarette and hush".[19]

In the European Journal of Media Studies, Anne Kustritz wrote that "Alejandro" showed Gaga's use of "unending semiotic shell game".[20] She felt that the names Alejandro, Roberto and Fernando, the word "Mexico", and the brief Spanish lyrics confirmed either that the song is set in Latin America or Gaga's lover is Hispanic. Kustritz believed that, beyond these instances, the song conveyed little about Mexico, Latin America or intercultural relationships. Confused by the song's constant shift of viewpoint from "I" to "You" to "She",[21] Kustritz noted how certain phrases[a] introduce themes but do not develop them further and "merely appear, like drunken lyrical mad lib fill-ins. Words seem to have been positioned in 'Alejandro' not because they convey meaning but because of how they sound, a strategy which reverses the usual insistence that the signified trumps the formal properties of the signifier."[22]

Critical reception and accolades

editEarlier critical reception to "Alejandro" was mixed. The song was called a summer-friendly track (BBC),[23] a "lush paean to a love that's 'hot like Mexico'" (MTV News),[15] "brilliantly catchy, deceptively simple and wonderfully melancholy" (MusicOMH),[24] and light-hearted (NME and Los Angeles Times).[25][26] Robert Copsey of Digital Spy praised the song's melodies, describing them as "deceptively catchy" and the lyrics as "wistful".[27] In a mixed review, Jon Blistein of L Magazine wrote that "Alejandro" and "Monster", another track from The Fame Monster, are "half-decent club/pop songs in their own right—and much more well-organized than 'Bad Romance'—they don't seem like complete thoughts".[28]

Comparisons with other artists, especially ABBA and Ace of Base's work, were constant in reviews.[29] Reviews from Slant Magazine and Rolling Stone believed the song paid a delightful tribute to ABBA.[14][30] It was described as a modernized version of an ABBA song by AllMusic and Pitchfork critics.[31][32] In a five-out-of-five-star review, Copsey recognized similarities to "La Isla Bonita" and Ace of Base songs, but felt that Gaga added "her own inimitable twist too".[27] Comparing the song to "Don't Turn Around" and "Fernando", Lindsey Fortier from Billboard added, "By the song's end, Alejandro, Fernando and Roberto aren't the only ones sent packing—the listener is dancing out right behind them."[9] Sociologist Mathieu Deflem dismissed the criticism of the song as an "ABBA rip-off" as he believed the reference to the band was intentional by RedOne who is also from Sweden.[33] Other comparisons of the song included with Madonna's 1987 single "Who's That Girl"[34] and Shakira in the chorus.[35]

Some reviews were negative. Sarah Hajibagheri from The Times dismissed it as a "painful Latino warble [and] a would-be Eurovision reject".[36] The Boston Globe's James Reed criticized it as "a tepid dance track" where she needlessly repeats the song's title.[37] Nathan Pensky of PopMatters felt that it is "a song truly made up of nothing, not even bothering to revel in its vacuity". Acknowledging its catchiness, Pensky opined that making a simple pop song was not enough, especially considering the quality of Gaga's other songs—"Bad Romance" and "Telephone".[38]

In retrospect, the song was ranked as one of Gaga's best by NME, The Guardian, Belfast Telegraph, Rolling Stone, Billboard and Vulture.[b] It was considered one of "Gaga's most enduring singles" by The Guardian,[39] and one of her catchiest pop songs by Vulture.[43] Belfast Telegraph approvingly highlighted "the inexplicably European lilt" in the spoken-word lyrics and "the femme-fatale chilliness of its chorus".[40] For Billboard, "The sweaty, stomping production ramps up during one of Gaga's simplest, most effective hooks to date."[42] On the song's 10-year anniversary, Mike Wass of Idolator complimented it for still sounding "as audacious and addictive as it did back then", concluding that "every element of 'Alejandro' comes together perfectly to create dance-pop bliss".[44]

"Alejandro" won an International Dance Music Award for Best Pop Dance Track and a BMI Pop Award for Most-Performed Songs of the Year.[45][46] It received nominations for a Gaygalan Award for International Song of the Year and a Rockbjörnen prize for Foreign Song of the Year.[47][48] A 2017 journal, published by Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts studying structural patterns in the melodies of earworm songs, compiled lists of catchiest tracks from 3,000 participants, in which "Alejandro" ranked number eight.[49]

Chart performance

editIn the US, "Alejandro" debuted at number 72 on the Billboard Hot 100 for the issue dated April 17, 2010. The song debuted on the Mainstream Top 40 chart at number 35, and the Hot Digital Songs chart at number 71, after selling 24,000 paid digital downloads according to Nielsen Soundscan.[50] It reached number five on the Hot 100, becoming Gaga's seventh consecutive top ten single in the US.[51] She became the most recent female artist to have her first seven singles reach top-ten in the US, since R&B singer Monica did so from 1995 to 1999, and with Gaga doing so in only 17 months.[52] "Alejandro" peaked at number four on the Mainstream Top 40 chart, becoming the first single by her not to reach the number one position there.[51] It also debuted on the Hot Dance Club Songs chart at 40[53] and reached the top in the issue dated July 7, 2010.[54] The song has sold 2.63 million digital downloads in the US as of February 2019,[55] making Gaga the second artist in digital history to amass seven consecutive two million sellers as a lead act.[56][57] The track was certified quadruple platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) in October 2017.[58] On the Canadian Hot 100, "Alejandro" peaked at number four on the issue dated May 8, 2010.[59]

On the ARIA Singles Chart (Australia), "Alejandro" peaked at number two, becoming Gaga's seventh top-five hit in the country.[60] "Alejandro" was certified quadruple platinum by the Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA) for shipment of 280,000 copies of the single.[61] The song peaked at number 11 on the New Zealand Top 40.[62] With the release of The Fame Monster in November 2009, "Alejandro" charted on the UK Singles Chart at number 75.[63] It peaked at number seven in 2010,[63] becoming her sixth top ten song in the UK.[64] According to the Official Charts Company, "Alejandro" has sold a total of 436,000 copies as of February 2014, and was certified platinum by the British Phonographic Industry (BPI) in 2020.[65][66] They listed it as the 37th best-selling vinyl single in the UK for the 2010s.[67] Across Europe, the song reached the top five in Austria, the Ultratop charts of Belgium (Flanders and Wallonia), Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Slovakia, Sweden and Switzerland, topping the charts in Finland, Greece, Poland, Romania and Russia.[68][69][70][71][72]

Music video

editDevelopment and release

editIn January 2010, Gaga began casting for the music video of "Alejandro".[73] It was directed by photographer Steven Klein,[74] whom Gaga considered the right choice as he understood her "I am what I wear" lifestyle, theater background, "love of music and love of the lie in art". She discussed her respect for Klein. "[W]e've been excited to collaborate and have a fashion photographer tell us a story, the story of my music through his lens and this idea of fashion and lifestyle."[75]

The video thematizes military homoeroticism and celebrates Gaga's admiration of the gay community.[76] She explained it is about the "purity of my friendships with my gay friends, and how I've been unable to find that with a straight man in my life. It's a celebration and an admiration of gay love—it confesses my envy of the courage and bravery they require to be together. In the video I'm pining for the love of my gay friends—but they just don't want me to be with them."[77] For Klein, the video is "about a woman's desire to resurrect a dead love and who can not face the brutality of her present situation. The pain of living without your true love."[78]

On the television talk show Larry King Live (2010), Gaga released a black-and-white portion from the video, in which she and her dancers perform variations on a sharp military march throughout.[76] The video premiered on Gaga's official website and her YouTube and Vevo accounts on June 8, 2010.[79] Days after the video's release, Gaga posted on her Twitter account: "Men are men ... A soldier is a soldier." Anne Kustritz wrote that it was posted at a time when she was publicly opposing "don't ask, don't tell", a policy by the United States Armed Forces, which prohibited discrimination against closeted homosexuals but also barred openly gay people from military service. Kustritz opined the video hardly portrayed this and it was unclear whether it was for or against the policy.[22]

Synopsis

editThe video was inspired by the Broadway musical Cabaret (1966), anti-fascism, religion, BDSM, sexual violence and the gay scene in 1920s Berlin.[22][80][81] It begins with soldiers in black leather uniforms (designed by Emporio Armani) in a cabaret.[82] This is followed by a close-up of a soldier passed out in fishnet stockings and heels as another lone soldier stares into the distance.[80] The scene then cuts to male dancers performing elaborate choreography while marching forward with a Star of David. As the song's intro begins, Gaga is shown leading a funeral procession and carrying the Sacred Heart on a pillow. When the lyrics begin, she sits on a throne in an elaborate headpiece and binocular-like eyepieces, holding a smoking pipe and watching her dancers perform a rigorous routine in the snow.[80] Playing the character Sally Bowles from Cabaret in the following scene, Gaga dances and simulates sex acts with three men on a stage with twin beds, intercut with shots of her lying on a larger bed dressed in a red latex nun outfit.[83]

Gaga appears dressed in a white hooded robe reminiscent of Joan of Arc, interspersed with a shot of her as a nun consuming rosary beads.[84] Gaga and her dancers in military uniforms are shown in a black-and-white sequence, performing a tribute to the late choreographer Bob Fosse, the director of the film version of Cabaret.[85] Gaga is seen in a blonde bob and a similar outfit to one of Liza Minnelli's performance costumes. The video shows a scene of her in a machine gun-equipped bra and her dancers. After a shot of her in an empty club, scenes of war breaking out flash by, and the lone soldier appears again. Going back to the Joan of Arc scene, she struggles with her dancers and disrobes. The video ends with her dressed as the nun, and the picture burns outwards.[80]

Anne Kustritz believed the video is possibly set in post-World War II Argentina where Gaga's character is seduced by Nazi fugitives assuming false Spanish identities but opined that the video barely shows Latin America or Mexico.[22] Author Joshua S. Walden saw vague allusions to a Hispanic location through the Catholic references with crucifix iconography, the red nun habit and the rosary.[86] James Montgomery thought the video was a tribute to pre-Nazi Germany, elaborating that the "carefully crafted close-ups, languorously smoked cigarettes and oppressively cut costumes" evoke the "artistically fertile but politically and economically difficult era" before Adolf Hitler's rise to power.[80]

Reception

editThe music video received mostly positive critical reviews. It was nominated for a MuchMusic Video Award for Most Streamed Video of the Year.[87] Praise focused on the video's dark themes and imagery. James Montgomery from MTV News commented that "Gaga has created a world that, while oppressive, also looks great"[80] and added in another piece that "she may have finally reached the point in her career where not even she can top herself."[88] Rolling Stone's Daniel Kreps labeled the video a "cinematic epic",[89] and Nate Jones of Time was impressed with the combination of "self-conscious ballsiness of Gaga and director Steven Klein".[90] Randall Roberts from the Los Angeles Times said that "the clip reinforces the notion that no one understands the convergence of image and music right now better than Gaga."[91] Other critics praised the video's quality but thought it was not on par with Gaga's previous videos, mainly "Bad Romance" and "Telephone".[92][85]

Critics took note of the video's length, shock value and complicated storyline. Jen Dose from National Post commented that "Alejandro" was another instance of Gaga's extravagance in her work.[93] The story was described as complicated by some critics, although Jed Gottlieb from the Boston Herald noted its lack of a happy ending.[94][95] Anthony Benigno from New York Daily News felt that "the shock songstress' new music video ... is chock full of bed-ridden S&M imagery that makes it look like the softcore answer to The Matrix" (1999).[83]

Reviewers saw references to artists Janet Jackson, Madonna, Laibach and The Three Stooges, as well as the films Frankenstein (1931), Triumph of the Will (1935) and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937).[22][96] Because of the video's military theme, comparisons were made to Jackson's "Rhythm Nation".[8] The connection to Madonna was made mainly with her film Evita (1996), and the videos for her songs "Like a Prayer", "Human Nature", "Express Yourself" and "Vogue".[8][97][92] According to Devon Thomas from CBS News, "Express Yourself" influenced Gaga's short, cropped hair and black blazer "set against the stark, post-industrialist mood" in "Alejandro". Thomas considered the video "a visual love letter" to Madonna, particularly of the Blond Ambition World Tour era.[98] The resemblance to "Vogue" was the black-and-white cinematography,[89] Dolce & Gabbana vest, Francesco Scognamiglio pantsuit and machine-gun bra.[c][99] Some reviewers defended Gaga; James Montgomery believed comparing the two artists merely because of the black and white cinematography and Gaga's bowl haircut was unfounded: "[T]hat's sort of selling their vision short".[100] Kreps thought the video's similarity to Madonna's work was because Klein had worked with her before filming "Alejandro".[89] Kara Warner of MTV News viewed that unlike Madonna, the style of "Alejandro" is "more cutting, masculine and militant".[76]

Religious iconography and themes

edit"Alejandro" created a media uproar after the release of the video because of its use of religious imagery.[101] One of the most discussed scenes in the video was when Gaga, wearing a nun's habit, swallowed rosary beads.[102] The Catholic League criticized the video for its use of religious imagery, accusing Gaga of "playing a Madonna copy-cat".[103][104] This was echoed by Mónica Herrera, who said Gaga's use of the rosary and nun's habit to make sexual references was reminiscent of Madonna's "Like a Prayer" video.[8] In an interview with MTV, Klein explained that this scene was Gaga's act of theophagy—"the desire to take in the holy". He said that the religious imagery was not supposed to signify anything negative, but only Gaga's "battle between the darker and lighter forces" as consolidated by Gaga's nun outfit. Klein added that the significance behind her mouth and eyes disappearing was "because she is withdrawing her senses from the world of evil and going inward towards prayer and contemplation".[104]

Many critics agreed that the religious imagery was a calculated move by Gaga to create controversy. One of them was Simon Voxick-Levinson from Entertainment Weekly: "Gaga wants to offend people. She's a provocateur. Gaga would probably be disappointed if no one was offended by her latest video. She's doing that stuff for a reason." He found the risks unoriginal and not as exciting as the ones in "Telephone". The New York Times' Jon Caramanica viewed the controversy as Gaga's attempt to take the "Queen of Pop" title from Madonna and found the religious imagery obvious and lazy.[105] Singer Katy Perry wrote in her Twitter account, "Using blasphemy as entertainment is as cheap as a comedian telling fart jokes." HuffPost suggested this was directed at Gaga even if she was not explicitly mentioned.[106] Perry responded that the tweet was not only about Gaga but more about her personal views of religion.[107] Her comments were criticized as hypocritical by BBC's Fraser McAlpine, who accused her of capitalizing on bi-curiosity with her song "I Kissed a Girl" (2008).[108]

Critics analyzed the military look and scenes. The soldiers wore German underwear from the Interwar period and black shirts and leather jackets; for the authors Sally Gray and Anusha Rutnam, they represented "Italian fascist-inflected male sartorial aesthetics".[109] In the Journal of LGBT Youth, Gilad Padva wrote that the military look is "queered by the explicit homoerotic photography, stylized choreography, the revealing outfits, their exposed muscles, and their sensual interactions". Padva wrote that the intimate interactions between the male dancers "(choreo)graphically challenge the hegemonic heteromasculinity and machismo",[81] and Gaga's dominance reverses "the notorious heteronormative power relations" where she becomes "the penetrator rather than the penetrated".[110] Literary critic Craig N. Owens wrote that some scenes of Gaga and the soldiers feature misplacement of the heart and the penis. For example, the beginning shows a muscular young man in a helmet and black briefs; he covers his crotch with a pistol. Owens thought the gun symbolizes the covered penis and indicates its displacement onto the upward-facing finial on the top of the helmet on his head. Owens believed the ending portrays organ replacement in that the top of Gaga's suit is changed into a machine gun-carrying bra. He found that this alluded to the ending scene of Gaga's "Bad Romance" video, in which she wears a pyrotechnic bra.[111]

Live performances

editBetween 2009 and 2011, Gaga performed "Alejandro" on The Monster Ball Tour. On the original version of the tour, she wore a silver bodysuit and was then carried by her crotch by one of her male dancers and lowered onto another male dancer, engaging in a threesome with them.[112] T'Cha Dunlevy from The Gazette said that "the song followed in fast order, with not quite enough to set [it] apart. It was one choreographed dance number after the next."[113] Jeremy Adams from Rolling Stone commented that the performance was "[one] of several moments ... that gave parents in the audience consternation".[114] Jim Harrington from The Mercury News compared Gaga's performance with that of an erotic dancer.[115] On the revamped show, Gaga smeared herself with fake blood during "Alejandro", as she took a bath in a fountain-like architecture on the stage, a replica of Bethesda Fountain in New York's Central Park.[116][117] Katrin Horn, a postdoctoral fellow in American studies, wrote that while performing "Alejandro", Gaga approached her audiences differently. She asked them to "put your hands up for equal rights!" instead of screaming to "dance" or "put your paws up" as she usually does. In this respect, she declared her desire to support political causes.[118]

In April 2010, Gaga performed "Alejandro" at the MAC AIDS Fund Pan-Asia Viva Glam launch in Tokyo. In a performance billed as "GagaKoh", she wore a doily lace dress and entered the stage in a procession inspired by a Japanese wedding. As the lights dimmed, she sat at her piano on the rotating stage and belted out "Speechless", followed by the performance of "Alejandro" where she was picked up by one of her dancers covered in talcum powder.[119][120] Gaga taped a medley of "Bad Romance" and "Alejandro" for the ninth season of American Idol in an episode aired in May 2010.[121][122][123] She was dressed in a black outfit while surrounded by shirtless dancers. During the chorus, a statue of the Virgin Mary had flames pouring out of its top, after which fog filled the stage as Gaga and her dancers performed a dance routine.[124] Luchina Fisher from ABC News called it a "thinly-veiled performance dripping with sex and violins" and "Gaga doing her best Madonna impression".[125] In July 2010, Gaga sang "Alejandro" on Today on a stage outside the studio.[126]

Gaga performed "Alejandro" at the Robin Hood Gala on May 9, 2011, to benefit the Robin Hood Foundation,[127] and on May 15, 2011, during Radio 1's Big Weekend in Carlisle, Cumbria.[128] On September 24, 2011, she performed it at the first iHeartRadio Music Festival, at the MGM Grand Garden Arena in Las Vegas.[129] It was also part of the setlist to Gaga's Born This Way Ball tour (2012–2013). The performance included her lounging on a meat couch and wearing her gun bra with half-naked men dancing around her.[130] For her 2014 tour, the ArtRave: The Artpop Ball, Gaga wore a green wig and leather hot pants for the performance of the song.[131] In 2017, she performed "Alejandro" during her shows at the Coachella Festival, while wearing a red crop-top sweatshirt.[132] The song was also part of the setlist of the Joanne World Tour (2017–2018), where she performed it in a mesh leather cut-out bodysuit,[133][134][135] and her Las Vegas residency show, Enigma (2018–2020).[136]

Track listing and formats

edit|

Digital download

The Remixes EP

French CD single and iTunes EP

|

UK CD single[137]

UK 7-inch vinyl[137]

UK iTunes bundle[137]

|

Credits and personnel

editCredits are adapted from the liner notes of The Fame Monster.[1]

- Lady Gaga – vocals, songwriter, co-producer, vocal arrangement, background vocals

- Nadir "RedOne" Khayat – songwriter, producer, vocal editing, vocal arrangement, background vocals, audio engineering, instrumentation, programming, recording at FC Walvisch, Amsterdam

- Eelco Bakker – audio engineering

- Johnny Severin – vocal editing

- Robert Orton – audio mixing at Sarm Studios, London, England

- Gene Grimaldi – audio mastering at Oasis Mastering, Burbank, California

Charts

edit

Weekly chartsedit

|

Monthly chartsedit

Year-end chartsedit

|

Certifications and sales

edit| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Australia (ARIA)[61] | 4× Platinum | 280,000‡ |

| Belgium (BEA)[224] | Platinum | 30,000* |

| Brazil (Pro-Música Brasil)[225] | Diamond | 250,000‡ |

| Denmark (IFPI Danmark)[226] | Platinum | 30,000^ |

| France (SNEP)[227] | Gold | 150,000* |

| Germany (BVMI)[228] | Platinum | 300,000^ |

| Italy (FIMI)[229] | 2× Platinum | 60,000* |

| New Zealand (RMNZ)[230] | Gold | 7,500* |

| Norway (IFPI Norway)[231] | Platinum | 60,000‡ |

| Russia (NFPF)[232] Ringtone |

4× Platinum | 800,000* |

| Spain (PROMUSICAE)[233] | Platinum | 40,000* |

| Spain (PROMUSICAE)[234] Since 2015 |

Gold | 30,000‡ |

| Sweden (GLF)[235] | Platinum | 40,000‡ |

| Switzerland (IFPI Switzerland)[236] | Platinum | 30,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[66] | Platinum | 600,000‡ |

| United States (RIAA)[58] | 4× Platinum | 2,630,000[55] |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

Release history

edit| Region | Date | Format(s) | Version | Label | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | November 9, 2009[d] | Digital download | Original | Interscope | [237] |

| France | [238] | ||||

| Sweden | [239] | ||||

| United States | April 20, 2010 | [5] | |||

| Europe | May 10, 2010 | Digital download | Remixes | [240] | |

| Canada | May 18, 2010 | [241] | |||

| United States | [242] [243] | ||||

| France | June 8, 2010 | Radio airplay | Original | Universal | [244] |

| United States | June 15, 2010 | CD | Remixes | Interscope | [245] |

| France | June 21, 2010 |

|

Original | [246] | |

| Italy | June 25, 2010 | Radio airplay | Universal | [247] | |

| United Kingdom | June 28, 2010 |

|

Polydor | [248] | |

| Germany | July 2, 2010 | CD | Interscope | [249] |

See also

edit- List of Billboard Hot 100 top-ten singles in 2010

- List of German airplay number-one songs

- List of number-one songs of the 2010s (Czech Republic)

- List of number-one singles of 2010 (Finland)

- List of number-one singles of the 2010s (Hungary)

- List of number-one singles of 2010 (Poland)

- List of Romanian Top 100 number ones of the 2010s

- List of number-one dance singles of 2010 (U.S.)

Notes

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Lady Gaga (2009). The Fame Monster (Booklet liner notes). Interscope Records. p. 3. 272 527-6.

- ^ Linder, Brian (November 23, 2009). "Lady Gaga – The Fame Monster Review". IGN. Archived from the original on June 13, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2022.

- ^ a b "Lady Gaga – Gaga Still Releasing 'Alejandro' in U.S." Contactmusic.com. April 5, 2010. Archived from the original on April 7, 2010. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- ^ a b "Lady GaGa Will Release 'Alejandro' as Next Single". MTV News. April 6, 2010. Archived from the original on April 14, 2011. Retrieved April 16, 2010.

- ^ a b "Radio Industry News, Music Industry Updates, Arbitron Ratings: 4/20 Mainstream". FMQB. Archived from the original on May 3, 2010. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ "Lady Gaga". Loaded. Season 1. February 15, 2010. 23:05 minutes in. Fuse TV.

"Alejandro" is my 'Fear of Men' – Monster.

- ^ a b Campbell, Kyle (October 2, 2018). "Lady Gaga: her top 10 songs, ranked". NME. Archived from the original on February 1, 2022. Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Herrera, Monica (June 10, 2010). "Lady Gaga 'Alejandro' Video Premieres, Channels Vintage Madonna". Billboard. Archived from the original on March 10, 2014. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Fortier, Lindsay (May 1, 2010). "New Releases: Lady Gaga 'Alejandro'". Billboard. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved May 3, 2010.

- ^ "Music Monday: Vittorio Monti's Czardas". Royal Philharmonic Society. Archived from the original on June 27, 2018. Retrieved June 1, 2018.

- ^ Burns, Woods & Lafrance 2015, p. 14.

- ^ a b Burns, Woods & Lafrance 2015, p. 22.

- ^ "Lady Gaga 'Alejandro' Sheet Music". Musicnotes.com. Sony/ATV Music Publishing. January 15, 2010. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017. Retrieved June 1, 2018.

- ^ a b c Cinquemani, Sal (November 18, 2009). "Lady Gaga: The Fame Monster". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on March 15, 2010. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ^ a b Ryan, Chris (October 11, 2009). "Song You Need To Know Now: Lady Gaga, 'Alejandro'". MTV News. Archived from the original on January 28, 2010. Retrieved February 9, 2010.

- ^ Burns, Woods & Lafrance 2015, p. 21.

- ^ Burns, Woods & Lafrance 2015, p. 19.

- ^ Burns, Woods & Lafrance 2015, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Barlow, Eve (December 30, 2018). "A Star Is Born Again: Lady Gaga's Vegas Residency Dazzles". Vulture. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved October 9, 2022.

- ^ Kustritz 2012, p. 40.

- ^ Kustritz 2012, pp. 40–41.

- ^ a b c d e f Kustritz 2012, p. 41.

- ^ "Single review: Lady Gaga – 'Alejandro'". BBC News. July 8, 2010. Archived from the original on April 3, 2017. Retrieved October 16, 2022.

- ^ Hubbard, Michael (November 23, 2009). "Lady Gaga: The Fame Monster, track-by-track". MusicOMH. Archived from the original on November 24, 2009. Retrieved February 9, 2010.

- ^ Patashnik, Ben (December 3, 2009). "Hate all you like, but it's getting harder and harder to deny she's a mistress of her art". NME. Archived from the original on April 13, 2010. Retrieved February 9, 2010.

- ^ Wood, Mikael (November 23, 2009). "Album review: Lady Gaga's The Fame Monster". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 15, 2009. Retrieved February 9, 2010.

- ^ a b Copsey, Robert (June 10, 2010). "Lady GaGa: 'Alejandro'". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on June 10, 2010. Retrieved June 25, 2010.

- ^ Blistein, Jon (November 25, 2009). "Monster of Pop?". L Magazine. Archived from the original on September 30, 2011. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- ^ Lester, Paul (November 20, 2009). "Lady Gaga The Fame Monster Review". BBC. Archived from the original on November 26, 2009. Retrieved February 7, 2010.

- ^ Dolan, Jon (November 23, 2009). "The Fame Monster: Lady Gaga: Review". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on December 19, 2010. Retrieved February 9, 2010.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas (November 29, 2009). "Lady Gaga > The Fame Monster". AllMusic. Archived from the original on April 27, 2011. Retrieved February 9, 2010.

- ^ Plagenhoef, Scott (January 13, 2010). "Pitchfork: Album Reviews: Lady Gaga: The Fame Monster". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on February 14, 2016. Retrieved February 9, 2010.

- ^ Deflem 2017, p. 204.

- ^ Fitzgerland, Brian R. (May 5, 2010). "Lady Gaga Performs, Aaron Kelly Goes Home". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on May 6, 2010. Retrieved May 6, 2010. (subscription required)

- ^ Sawdey, Evan (November 23, 2009). "Lady Gaga: The Fame Monster < Reviews". PopMatters. Archived from the original on January 29, 2010. Retrieved February 9, 2010.

- ^ Hajibagheri, Sarah (November 21, 2009). "Lady GaGa: The Fame Monster review". The Times. Archived from the original on July 1, 2010. Retrieved February 9, 2010.

- ^ Reed, James (November 24, 2009). "Lady Gaga's got a lot riding on The Fame Monster". Boston Globe. Archived from the original on June 30, 2012. Retrieved April 16, 2010.

- ^ Pensky, Nathan (September 1, 2010). "Beyond the Pale: Lady Gaga's 'Alejandro'". PopMatters. Archived from the original on October 2, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- ^ a b Cragg, Michael (April 23, 2020). "Lady Gaga's 30 greatest songs – ranked!". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 28, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- ^ a b White, Adam (June 5, 2020). "Lady Gaga's top 20 songs – ranked". Belfast Telegraph. Archived from the original on June 27, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- ^ Rosen, Jody (May 28, 2011). "The Ultimate Ranking of Lady Gaga's Catalogue". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 16, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- ^ a b Lipshutz, Jason (March 28, 2019). "Lady Gaga's 15 Best Songs: Critic's Picks". Billboard. Archived from the original on March 28, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- ^ a b He, Richard S. (August 30, 2020). "Every Lady Gaga Song, Ranked". Vulture. Archived from the original on September 12, 2020. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- ^ Wass, Mike (April 20, 2020). "Celebrating 10 Years Of Lady Gaga's 'Alejandro'". Idolator. Retrieved October 16, 2022.

- ^ "2011 International Dance Music Awards". Winter Music Conference. Archived from the original on February 14, 2011. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ "David Foster Named BMI Icon at 59th Annual BMI Pop Music Awards". Broadcast Music, Inc. May 18, 2011. Archived from the original on May 15, 2015. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ "Börja nominera dina favoriter till Gaygalan 2011" [Start nominating your favorites for Gaygalan 2011]. QX (in Swedish). Archived from the original on August 31, 2019. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ "Helt galet" [Absolutely crazy]. Aftonbladet (in Swedish). August 16, 2010. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ Jakubowski et al. 2017, pp. 122–135.

- ^ Pietrolungo, Silvio (April 8, 2010). "Rihanna Streaks to a Fourth Week Atop Hot 100". Billboard. Archived from the original on June 6, 2014. Retrieved April 21, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Lady Gaga Chart History (Hot 100)". Billboard. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ Caulfield, Keith; Pietrolungo, Silvio (May 20, 2010). "Chart Moves: Lady Gaga, Glee, Usher, Eminem and More". Billboard. Archived from the original on May 23, 2010. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ Caulfield, Keith (May 17, 2010). "Chart Highlights: Pop, Adult Pop, Latin Songs & More". Billboard. Archived from the original on July 1, 2010. Retrieved May 17, 2010.

- ^ a b "Lady Gaga Chart History (Dance Club Songs)". Billboard. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ a b Trust, Gary (February 10, 2019). "Ask Billboard: Lady Gaga's Career Sales & Streams; Ariana Grande Takes '7' to 1". Billboard. Archived from the original on February 10, 2019. Retrieved February 11, 2019. (subscription required)

- ^ Grein, Paul (December 29, 2010). "Week Ending Dec. 26, 2009: What Santa Brought". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on January 2, 2011. Retrieved December 30, 2010.

- ^ Trust, Gary (June 12, 2012). "Ask Billboard: Was Lady Gaga's Born This Way a Disappointment?". Billboard. Archived from the original on May 23, 2013. Retrieved June 12, 2012.

- ^ a b "American single certifications – Lady Gaga – Alejandro". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- ^ a b "Lady Gaga Chart History (Canadian Hot 100)". Billboard. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ a b "Lady Gaga – Alejandro". ARIA Top 50 Singles. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ a b "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2024 Singles" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ a b "Lady Gaga – Alejandro". Top 40 Singles. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Official Singles Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ "Look through every Lady Gaga single and album cover". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on October 16, 2022. Retrieved October 16, 2022.

- ^ Justin, Myers (February 28, 2014). "Lady Gaga's Official Top 10 Biggest Selling UK Singles Revealed!". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on November 15, 2013. Retrieved November 12, 2013.

- ^ a b "British single certifications – Lady Gaga – Alejandro". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- ^ Moss, Liv (April 13, 2015). "The Official Top 40 Biggest Vinyl Singles and Albums of the decade so far". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on April 15, 2015. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- ^ a b "Lady Gaga – Alejandro" (in French). Ultratop 50. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ a b "Lady Gaga Chart History (Greece Digital Song Sales)". Billboard. Archived from the original on October 13, 2019. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ^ a b "Listy bestsellerów, wyróżnienia :: Związek Producentów Audio-Video". Polish Airplay Top 100. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ a b "Romanian Top 100 Airplay 23.07.2010". Romanian Top 100. July 17, 2010. Archived from the original on August 6, 2010. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- ^ "Chart Search". Tophit for Lady Gaga. Archived from the original on November 1, 2016. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ^ Balls, David (January 8, 2010). "GaGa 'wants David Walliams for video'". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on April 1, 2012. Retrieved February 1, 2010.

- ^ Axelrod, Nick (March 23, 2010). "Steven Klein Said Shooting Lady Gaga Video". Women's Wear Daily. Archived from the original on March 27, 2010. Retrieved March 24, 2010.

- ^ Dinh, James (May 7, 2010). "Lady Gaga Says 'Alejandro' Video Will Be About 'Fashion And Lifestyle'". MTV News. Archived from the original on May 10, 2010. Retrieved May 19, 2010.

- ^ a b c Warner, Kara (June 1, 2010). "Lady Gaga Offers 'Alejandro' Video Sneak Peek On 'Larry King Live'". MTV News. Archived from the original on June 2, 2010. Retrieved June 2, 2010.

- ^ Moran, Caitlin (May 23, 2010). "Come party with Lady Gaga". The Times. Archived from the original on May 22, 2010. Retrieved May 24, 2010.

- ^ Vena, Jocelyn (June 9, 2010). "Lady Gaga's 'Alejandro' Director Explains Video's Painful Meaning". MTV News. Archived from the original on June 12, 2010. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ^ "New music videos of the week: 'Alejandro,' Eminem, Vengaboys". The Independent. June 9, 2010. Archived from the original on October 19, 2012. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f Montgomery, James (June 8, 2010). "Lady Gaga's 'Alejandro' Video: German Expressionism With A Beat!". MTV News. Archived from the original on June 11, 2010. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- ^ a b Padva 2018, p. 187.

- ^ Gray & Rutnam 2014, p. 52.

- ^ a b Benigno, Anthony (June 8, 2010). "Lady Gaga 'Alejandro' music video turns up the S&M heat with fetish imagery and a ravaged nun". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on June 11, 2010. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ^ Vena, Jocelyn (June 9, 2010). "Lady Gaga's 'Alejandro' Video: A Fashion Cheat Sheet". MTV News. Archived from the original on October 15, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- ^ a b Cady, Jennifer (June 8, 2010). "'Alejandro' Premiere = Nine Minutes of Lady Gaga & Bunch of Shirtless Men". E!. Archived from the original on September 12, 2011. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ Walden 2014, p. 209.

- ^ "MMVA 2011 Nominees". MuchMusic. Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ^ Montgomery, James (June 8, 2010). "Lady Gaga's 'Alejandro' Video Might Not Top 'Telephone,' But Why Should It?". MTV News. Archived from the original on June 11, 2010. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ^ a b c Kreps, Daniel (June 8, 2010). "'Alejandro' Director Breaks Down Lady Gaga's Racy Video". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 12, 2012. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ Jones, Nate (June 8, 2010). "Lady Gaga Releases 'Alejandro' Video, Bowl-Cut Enthusiasts Rejoice". Time. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ Roberts, Randall (June 8, 2010). "Lady Gaga releases new video, will go head-to-head with the Strokes at Lollapalooza". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 10, 2010. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ^ a b Odell, Amy (June 8, 2010). "A Breakdown of Lady Gaga's 'Alejandro' Looks". The Cut. Archived from the original on June 11, 2010. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ Dose, Jen (June 9, 2010). "Scandal Sheet: Lady Gaga's 'Alejandro' Debuts". National Post. Archived from the original on July 1, 2010. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ^ Gottlieb, Jed (June 9, 2010). "Lady Gaga's 'Alejandro' video is a sad misstep". Boston Herald. Archived from the original on June 11, 2010. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ^ Wete, Brad (June 8, 2010). "Lady Gaga premieres 'Alejandro' mini-movie: Watch it here". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on January 18, 2012. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ Padva 2018, pp. 188–189.

- ^ Anderson, Kyle (June 8, 2010). "Lady Gaga's 'Alejandro' Video: A Guide to Its Madonna References". MTV News. Archived from the original on June 10, 2010. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ^ a b Thomas, Devon (June 8, 2010). "Lady Gaga 'Alejandro' Music Video Has Singer's Guns Blazing". CBS News. Archived from the original on June 10, 2010. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ^ Gray & Rutnam 2014, p. 55.

- ^ "Comparing Lady Gaga's 'Alejandro' Video to Madonna". MTV News. June 8, 2010. Archived from the original on March 24, 2012. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ Pickard, Anna (June 9, 2010). "Who's most offended by Lady Gaga's 'Alejandro'?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 26, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ^ Ziegbe, Mawuse (July 9, 2010). "Does Lady Gaga's 'Alejandro' Video Go Too Far?". MTV News. Archived from the original on February 13, 2012. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ "Catholic League: For Religious and Civil Rights". Catholic League. June 9, 2010. Archived from the original on June 15, 2010. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ^ a b Montgomery, James (June 9, 2010). "Lady Gaga's 'Alejandro' Director Defends Video's Religious Symbolism". MTV News. Archived from the original on June 12, 2010. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ^ Vena, Jocelyn (June 11, 2010). "Lady Gaga Wants to Offend with 'Alejandro,' Experts Say". MTV News. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ "Katy Perry Slams Lady Gaga's 'Blasphemous' New Video". HuffPost. June 8, 2010. Archived from the original on June 13, 2010. Retrieved June 16, 2010.

- ^ Vena, Jocelyn (June 14, 2010). "Katy Perry Explains Her Lady Gaga 'Blasphemy' Tweet". MTV News. Archived from the original on June 17, 2010. Retrieved June 14, 2010.

- ^ McAlpine, Fraser (June 9, 2010). "Lady GaGa – 'Alejandro'". BBC. Archived from the original on December 19, 2020. Retrieved October 18, 2022.

- ^ Gray & Rutnam 2014, pp. 53.

- ^ Padva 2018, p. 188.

- ^ Owens 2014, p. 101.

- ^ Stevenson, Jane (November 29, 2009). "Lady Gaga puts on a Monster show". Toronto Sun. Archived from the original on July 5, 2017. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ^ Dunlevy, T'Cha (November 28, 2009). "Concert review: Lady Gaga romances Bell Centre crowd, Nov. 27". The Gazette. Archived from the original on June 4, 2010. Retrieved February 9, 2010.

- ^ Adams, Jeremy (December 2, 2009). "Live Review: Lady Gaga Brings Her Pop Theatricality to Boston in First U.S. 'Monster Ball' Show". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 27, 2011. Retrieved February 9, 2010.

- ^ Harrington, Jim (December 14, 2009). "Lady Gaga thrills S.F. crowd with strange, sexy show". Mercury News. ISSN 0747-2099.

- ^ Browne, David (August 5, 2010). "Inside Lady Gaga's Monster Ball, Summer's Biggest Tour". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 16, 2022. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- ^ Montgomery, James (June 29, 2010). "Lady Gaga Goes the Distance at Montreal Monster Ball Tour Kickoff". MTV News. Archived from the original on October 8, 2022. Retrieved October 8, 2022.

- ^ Horn 2017, p. 236.

- ^ "Lady Gaga Puts On White Hot Viva Glam Performance in Japan". MTV News. April 22, 2010. Archived from the original on April 24, 2010. Retrieved April 22, 2010.

- ^ "Tokyo goes gaga for Lady Gaga – and charity". CNN. April 22, 2010. Archived from the original on August 6, 2016. Retrieved December 27, 2016.

- ^ Ditzian, Erik (April 29, 2010). "Lady Gaga Tapes American Idol Performance". MTV News. Archived from the original on May 2, 2010. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ^ B. Vary, Adam (April 29, 2010). "American Idol Top 6 Results on the Scene". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on May 5, 2010. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ^ Dinh, James (April 19, 2010). "Lady Gaga Tweets About Upcoming American Idol Appearance". MTV News. Archived from the original on April 25, 2010. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ^ Carroll, Larry (May 6, 2010). "Lady Gaga Brings 'Alejandro' To American Idol". MTV News. Archived from the original on May 6, 2010. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ^ Fisher, Luchina (May 5, 2010). "Idol Final Four: Aaron Kelly Gets the Boot". ABC News. Archived from the original on September 16, 2012. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ^ Herrera, Monica (July 8, 2010). "Lady Gaga Plays Today Show, Announces 'Remix' U.S. Release". Billboard. Archived from the original on May 24, 2013. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- ^ Harp, Justin (May 11, 2011). "Lady GaGa gig raises millions for NY charity". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on October 8, 2022. Retrieved October 8, 2022.

- ^ Sperling, Daniel (May 16, 2011). "Lady GaGa closes Radio 1's Big Weekend". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on May 18, 2011. Retrieved May 16, 2011.

- ^ Stransky, Tanner (September 25, 2011). "iHeartRadio Music Festival Las Vegas: Lady Gaga, Sting, Jennifer Lopez perform". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on October 8, 2022. Retrieved October 8, 2022.

- ^ Pager, Nicole (January 21, 2013). "Lady Gaga Brings 'Born This Way Ball' to Los Angeles: Live Review". Billboard. Archived from the original on July 4, 2013. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- ^ Carlson, Adam (May 7, 2014). "Lady Gaga's artRAVE: The ARTPOP Ball Shape-Shifts Through Atlanta". Billboard. Archived from the original on July 4, 2013. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

- ^ Hall, Gerrad (April 16, 2017). "Lady Gaga debuts new single, 'The Cure,' at Coachella". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on September 9, 2017. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

- ^ "Lady Gaga reigns supreme in Wrigley Field headlining debut". Chicago Sun-Times. August 26, 2017. Archived from the original on September 8, 2017. Retrieved September 8, 2017.

- ^ Fisher, Lauren Alexis (August 10, 2017). "Lady Gaga's Joanne Tour Costumes Include Swarovski Crystals, Leather Fringe, and Cowboy Hats". Harper's Bazaar. Archived from the original on November 16, 2017. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ^ Derdeyn, Stuart (August 2, 2017). "Lady Gaga: Live review of Joanne World Tour at Vancouver's Rogers Arena". The Vancouver Sun. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved October 9, 2022.

- ^ Spanos, Brittany (December 29, 2018). "Review: Lady Gaga Maintains 'Poker Face' During Stellar Vegas Debut". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on December 30, 2018. Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- ^ a b c "'Alejandro' UK release date revealed!". Ladygaga.co.uk. May 26, 2010. Archived from the original on June 7, 2010. Retrieved June 2, 2010.

- ^ "Lady Gaga – Alejandro" (in German). Ö3 Austria Top 40. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ "Lady Gaga – Alejandro" (in Dutch). Ultratop 50. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ "Top 5 Brasil Música – Semanal: 05/07/2010 à 09/07/2010" (in Portuguese). Crowley Broadcast Analysis. Archived from the original on July 14, 2010. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ^ "Lady Gaga Chart History (Canada AC)". Billboard. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ^ "Lady Gaga Chart History (Canada CHR/Top 40)". Billboard. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ^ "Lady Gaga Chart History (Canada Hot AC)". Billboard. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Lady Gaga — Alejandro. TopHit. Retrieved October 7, 2024.

- ^ "Airplay Radio Chart 2010 Year End Edition". 2010. Retrieved April 5, 2024.

- ^ "ČNS IFPI" (in Czech). Hitparáda – Radio Top 100 Oficiální. IFPI Czech Republic. Note: Select 34. týden 2010 in the date selector. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ "Lady Gaga – Alejandro". Tracklisten. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ "Hits of the World: European Hot 100 Singles". Billboard. Vol. 122, no. 30. July 31, 2010. p. 51.

- ^ "Lady Gaga: Alejandro" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ "Lady Gaga – Alejandro" (in French). Les classement single. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ "Lady Gaga – Alejandro" (in German). GfK Entertainment charts. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- ^ "Archívum – Slágerlisták – MAHASZ" (in Hungarian). Dance Top 40 lista. Magyar Hanglemezkiadók Szövetsége. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ^ "Archívum – Slágerlisták – MAHASZ" (in Hungarian). Rádiós Top 40 játszási lista. Magyar Hanglemezkiadók Szövetsége. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- ^ "Archívum – Slágerlisták – MAHASZ" (in Hungarian). Single (track) Top 40 lista. Magyar Hanglemezkiadók Szövetsége. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ "The Irish Charts – Search Results – Alejandro". Irish Singles Chart. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ^ "Lady Gaga – Alejandro". Top Digital Download. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ "Lady Gaga Chart History (Luxembourg Digital Song Sales)". Billboard. Archived from the original on October 28, 2019. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ^ "Enrique Iglesias y Juan Luis Guerra los favoritos del público". Terra Networks (in Spanish). Telefonica Group. September 6, 2010. Archived from the original on February 21, 2013. Retrieved June 1, 2012.

- ^ "Nederlandse Top 40 – Lady Gaga" (in Dutch). Dutch Top 40. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ "Lady Gaga – Alejandro" (in Dutch). Single Top 100. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ "Lady Gaga – Alejandro". VG-lista. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ "Lady Gaga Chart History (Portugal Digital Song Sales)". Billboard. Archived from the original on October 28, 2019. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ^ "Media Forest – Weekly Charts. Media Forest. Retrieved October 7, 2024. Note: Romanian and international positions are rendered together by the number of plays before resulting an overall chart.

- ^ "Media Forest – Weekly Charts. Media Forest. Retrieved October 7, 2024. Note: Select 'Songs – TV'. Romanian and international positions are rendered together by the number of plays before resulting an overall chart.

- ^ "Top Radio Hits Russia Weekly Chart: Jul 15, 2010". TopHit. Retrieved October 7, 2024.

- ^ "Official Scottish Singles Sales Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ "ČNS IFPI" (in Slovak). Hitparáda – Radio Top 100 Oficiálna. IFPI Czech Republic. Note: insert 201022 into search. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ "Gaon Digital Chart: Week 1, 2010". Gaon Music Chart. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- ^ "Lady Gaga – Alejandro" Canciones Top 50. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ "Lady Gaga – Alejandro". Singles Top 100. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ "Lady Gaga – Alejandro". Swiss Singles Chart. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ "Top Radio Hits Ukraine Weekly Chart: Jul 8, 2010". TopHit. Retrieved October 7, 2024.

- ^ "Lady Gaga Chart History (Adult Contemporary)". Billboard. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ "Lady Gaga Chart History (Adult Pop Songs)". Billboard. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ "Lady Gaga Chart History (Hot Latin Songs)". Billboard. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ "Lady Gaga Chart History (Pop Songs)". Billboard. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ "Lady Gaga Chart History (Rhythmic)". Billboard. Retrieved November 21, 2014.

- ^ "Pop Rock" (in Spanish). Record Report. August 21, 2010. Archived from the original on August 20, 2010.

- ^ "OLiS – oficjalna lista airplay" (Select week 20.05.2023–26.05.2024.) (in Polish). OLiS. Retrieved October 7, 2024.

- ^ "OLiS – oficjalna lista airplay" (Select week 23.03.2024–29.03.2024.) (in Polish). OLiS. Retrieved October 7, 2024.

- ^ "Top Radio Hits Romania Weekly Chart: Sep 26, 2024". TopHit. Retrieved September 29, 2024.

- ^ "Brasil Hot 100 Airplay (Jul 18, 2010)". Billboard Brasil. No. 11. BPP Promoções e Publicações. August 2010. p. 84.

- ^ "Brasil Hot Pop & Popular: Hot Pop Songs (Jul 18, 2010)". Billboard Brasil. No. 11. BPP Promoções e Publicações. August 2010. p. 85.

- ^ "Top Radio Hits Global Monthly Chart: July 2010". TopHit. Retrieved October 7, 2024.

- ^ "Top Radio Hits Russia Monthly Chart: July 2010". TopHit. Retrieved October 7, 2024.

- ^ "Top Radio Hits Ukraine Monthly Chart: July 2010". TopHit. Retrieved October 7, 2024.

- ^ "Top Radio Hits Global Monthly Chart: Jun 2011". TopHit. Retrieved October 7, 2024.

- ^ "Top Radio Hits Russia Monthly Chart: June 2011". TopHit. Retrieved October 7, 2024.

- ^ "Top Radio Hits Romania Monthly Chart: September 2024". TopHit. Retrieved October 6, 2024.

- ^ "ARIA Charts – End Of Year Charts – Top 100 Singles". Australian Recording Industry Association. Archived from the original on December 5, 2010. Retrieved January 11, 2011.

- ^ "Jahreshitparade 2010" [Annual hit parade 2010]. Hitradio Ö3 (in German). Hung Medien. Archived from the original on February 27, 2011. Retrieved December 30, 2010.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten 2010 (Flanders)" (in Dutch). Ultratop. Hung Medien. Archived from the original on January 26, 2014. Retrieved December 26, 2010.

- ^ "Rapports annuels 2010 – Singles" (in French). Ultratop. Archived from the original on February 9, 2014. Retrieved December 26, 2010.

- ^ "2010 Year-End Canadian Hot 100 Songs". Billboard. December 9, 2009. Archived from the original on March 23, 2015. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- ^ "Top Radio Hits Global Annual Chart 2010". TopHit. Retrieved October 7, 2024.

- ^ "Airplay Radio Chart 2010 Year End Edition". 2010. Retrieved April 5, 2024.

- ^ "Track 2010 Top-50". Tracklisten (in Danish). Nielsen Music Control. 2010. Archived from the original on November 23, 2010.

- ^ "2010 Year-End European Hot 100 Songs". Billboard. Archived from the original on July 13, 2014. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- ^ "Top de l'année Top Singles 2010" [Top Singles of the Year 2010] (in French). Syndicat National de l'Édition Phonographique. Archived from the original on November 5, 2021. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ "Top 100 Single-Jahrescharts". GfK Entertainment (in German). offiziellecharts.de. Archived from the original on January 30, 2017. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ^ "Dance Top 100 – 2010". Mahasz. Archived from the original on June 3, 2020. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ^ "Rádiós Top 100 – hallgatottsági adatok alapján – 2010". Mahasz. Archived from the original on June 2, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ^ "2010 Year End Italian Singles Chart". FIMI. 2011. Archived from the original on January 21, 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2011.

- ^ "Top 100-Jaaroverzicht van 2010". Dutch Top 40. Archived from the original on July 18, 2013. Retrieved October 22, 2019.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten – Single 2010" [Annual Reviews – Single 2010] (in Dutch). MegaCharts. Archived from the original on November 30, 2019. Retrieved October 22, 2019.

- ^ "Topul celor mai difuzate piese în România în 2010" [The top of the most played songs in Romania in 2010]. România Liberă (in Romanian). Archived from the original on January 6, 2011. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ^ "Top Radio Hits Russia Annual Chart 2010". TopHit. Archived from the original on April 28, 2024. Retrieved October 7, 2024.

- ^ "2010 Spanish Year-end charts" (PDF) (in Spanish). PROMUSICAE. December 29, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 3, 2011. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

- ^ "Årslista Singlar – År 2010" [Annual Singles List – Year 2010] (in Swedish). Sverigetopplistan. Archived from the original on April 23, 2020. Retrieved October 22, 2019.

- ^ "2010 Year End Swiss Singles Chart". Swiss Music Charts. 2011. Archived from the original on July 12, 2011. Retrieved January 2, 2011.

- ^ "Top Radio Hits Ukraine Annual Chart 2010". TopHit. Retrieved October 7, 2024.

- ^ "UK Year-End Charts 2010". Official Charts Company. ChartsPlus. Archived from the original on July 1, 2010. Retrieved August 13, 2015.

- ^ "2010 Year-End Billboard Hot 100 Songs". Billboard. Archived from the original on March 20, 2015. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- ^ "2010 Year-End Billboard Adult Contemporary Songs". Billboard. Archived from the original on April 8, 2015. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- ^ "Adult Pop Songs – Year-End 2010". Billboard. Archived from the original on April 18, 2019. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ "2010 Year-End Hot Dance Club Songs". Billboard. December 9, 2009. Archived from the original on June 21, 2014. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- ^ "2010 Year-End Pop Songs". Billboard. Archived from the original on May 18, 2013. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- ^ "Top Radio Hits Global Annual Chart 2011". TopHit. Retrieved October 7, 2024.

- ^ "Dance Top 100 – 2011". Mahasz. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ^ "Rádiós Top 100 – hallgatottsági adatok alapján – 2011". Mahasz. Archived from the original on June 3, 2020. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ^ "Top Radio Hits Russia Annual Chart 2011". TopHit. Retrieved October 7, 2024.

- ^ "Top Radio Hits Ukraine Annual Chart 2011". TopHit. Retrieved October 7, 2024.

- ^ "Rádiós Top 100 - hallgatottsági adatok alapján - 2023" (in Hungarian). MAHASZ. Archived from the original on January 25, 2024. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

- ^ "Ultratop − Goud en Platina – singles 2010". Ultratop. Hung Medien. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

- ^ "Brazilian single certifications – Lady Gaga – Alejandro" (in Portuguese). Pro-Música Brasil. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ "Danish single certifications – Lady Gaga – Alejandro". IFPI Danmark. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

- ^ "French single certifications – Lady Gaga – Alejandro" (in French). Syndicat National de l'Édition Phonographique. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

- ^ "Gold-/Platin-Datenbank (Lady Gaga; 'Alejandro')" (in German). Bundesverband Musikindustrie. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

- ^ "Italian single certifications – Lady Gaga – Alejandro" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Retrieved September 28, 2011. Select "2010" in the "Anno" drop-down menu. Type "Alejandro" in the "Filtra" field. Select "Singoli" under "Sezione".

- ^ "Latest Gold / Platinum Singles". Radioscope. August 21, 2011. Archived from the original on August 31, 2011. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

- ^ "Norwegian single certifications – Lady Gaga – Alejandro" (in Norwegian). IFPI Norway. Retrieved November 19, 2021.

- ^ "Российская индустрия звукозаписи 2011" (PDF) (in Russian). Lenta. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 17, 2019. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ "Spanish single certifications" (in Spanish). Productores de Música de España. Retrieved September 28, 2011. Select Canciones under "Categoría", select 2010 under "Año". Select 42 under "Semana". Click on "BUSCAR LISTA".

- ^ "Spanish single certifications – Lady Gaga – Alejandro". El portal de Música. Productores de Música de España. Retrieved March 18, 2024.

- ^ "Guld- och Platinacertifikat − År 2010" (PDF) (in Swedish). IFPI Sweden. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 17, 2011. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

- ^ "The Official Swiss Charts and Music Community: Awards ('Alejandro')". IFPI Switzerland. Hung Medien. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

- ^ "Alejandro: Belgium Digital download". iTunes Store. Archived from the original on June 27, 2010. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- ^ "Alejandro: France Digital download". iTunes Store. Archived from the original on September 22, 2011. Retrieved November 15, 2010.

- ^ "Alejandro: Sweden Digital download". iTunes Store. Archived from the original on March 10, 2010. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- ^ Digital releases across Europe for "Alejandro":

- "Alejandro – Lady Gaga" (in French). iTunes Store. January 2010. Archived from the original on August 30, 2010. Retrieved June 8, 2010.

- "Alejandro – Lady GaGa". iTunes Store. January 2010. Archived from the original on January 13, 2012. Retrieved June 8, 2010.

- "Alejandro – Lady GaGa". iTunes Store. January 2010. Archived from the original on January 12, 2012. Retrieved June 8, 2010.

- "Alejandro van – Lady Gaga" (in Dutch). iTunes Store. January 2010. Archived from the original on January 13, 2012. Retrieved June 8, 2010.

- "Alejandro – Lady GaGa". iTunes Store. January 2010. Archived from the original on September 25, 2011. Retrieved June 8, 2010.

- "Alejandro – Lady GaGa". iTunes Store. January 2010. Archived from the original on January 12, 2012. Retrieved June 8, 2010.

- "Alejandro – Lady GaGa". iTunes Store. January 2010. Archived from the original on January 13, 2012. Retrieved June 8, 2010.

- "Alejandro – Lady GaGa" (in German). iTunes Store. January 2010. Archived from the original on January 12, 2012. Retrieved June 8, 2010.

- ^ "Alejandro (The Remixes) – Lady Gaga". iTunes Store. January 2010. Archived from the original on September 15, 2011. Retrieved June 8, 2010.

- ^ "Alejandro – Lady Gaga – The Remixes EP". Amazon. Archived from the original on February 16, 2015. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ "Alejandro – Lady Gaga – The Remixes EP". iTunes Store. January 2010. Archived from the original on May 22, 2010. Retrieved May 19, 2010.

- ^ Cadet, Thierry (June 8, 2010). "Lady GaGa : le clip intégral de "Alejandro" !". Pure Charts in France (in French). Retrieved September 11, 2021.

- ^ "Alejandro the Remixes [Single]". Amazon. Archived from the original on June 6, 2010. Retrieved September 25, 2013.

- ^ "CD Single Release in France". Archived from the original on February 13, 2013. Retrieved January 12, 2011.

- ^ "EarOne | Radio Date, le novita musicali della settimana" (in Italian). EarOne. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- ^ "'Alejandro' [7' Vinyl]". Amazon (United Kingdom). Archived from the original on March 15, 2016. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ "Lady Gaga German CD single release". Ladygaga.de. July 2, 2010. Archived from the original on July 1, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

Literary sources

edit- Burns, Lori; Woods, Alyssa; Lafrance, Marc (March 2015). "The Genealogy of a Song: Lady Gaga's Musical Intertexts on The Fame Monster (2009)". Twentieth-Century Music. 12 (1). Cambridge University Press: 3–35. doi:10.1017/S1478572214000176. S2CID 194128676.

- Deflem, Mathieu (2017). "Art Pop: The Styles of Lady Gaga". Lady Gaga and the Sociology of Fame: the Rise of a Pop Star in an Age of Celebrity. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 189–210. ISBN 978-1-137-58468-7.

- Horn, Katrin (2017). "Taking Pop Seriously: Lady Gaga as Camp". Women, Camp, and Popular Culture: Serious Excess. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 193–252. ISBN 978-3-319-64845-3.

- Jakubowski, Kelly; Finkel, Sebastian; Stewart, Lauren; Müllensiefen, Daniel (May 2017). "Dissecting an Earworm: Melodic Features and Song Popularity Predict Involuntary Musical Imagery" (PDF). Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts. 11 (2). American Psychological Association: 122–135. doi:10.1037/aca0000090. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 4, 2022. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- Iddon, Martin; Marshall, Melanie L., eds. (2014). Lady Gaga and Popular Music: Performing Gender, Fashion, and Culture. Routledge Studies in Popular Music. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-07987-2.

- Gray, Sally; Rutnam, Anusha (2014). "Her Own Real Thing: Lady Gaga and the House of Fashion". Lady Gaga and Popular Music : Performing Gender, Fashion, and Culture. Routledge. pp. 43–66. ISBN 978-1-134-07987-2.

- Owens, Craig N. (2014). "Celebrity without Organs". Lady Gaga and Popular Music : Performing Gender, Fashion, and Culture. Routledge. pp. 94–116. ISBN 978-1-134-07987-2.

- Kustritz, Anne (2012). "MP3s, rebundled debt, and performative economics – Deferral, derivatives, and digital commodity fetishism in Lady Gaga's spectacle of excess". NECSUS European Journal of Media Studies. 2 (23–54). Amsterdam University Press: 35–54. doi:10.5117/NECSUS2012.2.KUST.

- Padva, Gilad (January 2, 2018). "Queer Nostalgia in Cinema and Pop Culture". Journal of LGBT Youth. 15 (1). Palgrave Macmillan: 173–199. doi:10.1057/9781137266347. ISBN 978-1-137-26633-0.

- Walden, Joshua S. (2014). "Conclusion". Sounding authentic: the rural miniature and musical modernism. Oxford University Press. pp. 203–210. ISBN 978-0-199-33467-4.