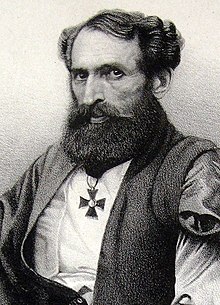

Alexander Kasimovich Kazembek

Alexander Kasimovich Kazembek[a] (22 June 1802 or 3 August 1803 – 27 November 1870), was an orientalist, historian and philologist in the Russian Empire.

Alexander Kasimovich Kazembek | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 22 June 1802 or 3 August 1803 Rasht, Qajar Iran |

| Died | 27 November 1870 (aged 68) Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Resting place | Pavlovsk, Saint Petersburg |

| Occupation | Orientalist, historian, philologist |

| Language | |

| Notable awards |

|

| Relatives | Alexander Kazembek (great-grandson) |

Born in Rasht, Qajar Iran, Kazembek hailed from a prominent family originally based in Derbent, a city historically tied to Iran. Kazembek grew up during the tumultuous period of the Russo-Iranian war of 1804–1813, which culminated in the Russian conquest of Derbent in 1806. His father, Hajji Qasim Kazem-Beg, was appointed the principal qazi (Muslim judge) of Derbent by the Russians, and in 1811, Kazembek and his mother rejoined him there. However, after his father was accused of treason, the latter was banished to Astrakhan, where Kazembek joined him in 1821.

In Astrakhan, Kazembek encountered Scottish missionaries and converted from Islam to Christianity, which led to severe opposition from his father. Despite this, he remained committed to his new faith and was baptized by the Scottish mission in July 1823. Following his conversion, Kazembek entered the compulsorily Russian imperial service and later joined Kazan University in January 1826. He advanced rapidly in his academic career, becoming a professor of Arabic and Persian literature and dean, and earning international recognition for his contributions to Oriental studies.

In 1849, Kazembek moved to the University of Saint Petersburg, where he was appointed as a professor of Persian. He was appointed dean of the Faculty of Oriental Studies in 1855, and he founded the Department of Oriental History in 1863. After his death, he was buried in Saint Petersburg's district Pavlovsk, where had probably stayed for some days before his death.

Notable for his deep engagement with both English-speaking and Russian cultures, Kazembek was a distinguished scholar in Persian and Turkish studies. His expertise in these fields, similar to that of the Russian orientialists Vasily Bartold and Vladimir Minorsky, established him as a pioneer to both the prominent school of Iranian studies in Saint Petersburg and the scholarly traditions in London. He was the great-grandfather Mladorossi founder Alexander Kazembek.

Biography

editBackground and early life

editKazembek was born in 22 June 1802 or 3 August 1803, in the town of Rasht in Qajar Iran.[1] His family was one of the leading families of Derbent, a town on the western coast of the Caspian Sea with deep historical ties to Iran. Since the 1500s, Derbent had been under Iranian rule.[2] During the wars of the Iranian shah (king) Nader Shah (r. 1736–1747), Kazembek's grandfather Nasir Mohammad-Beg moved to the Derbent region and eventually became the minister of the semi-independent ruler of the Quba Khanate, Fath-Ali Khan.[2][3] Kazembek's father, the Muslim cleric Hajji Qasim Kazem-Beg was born in Derbent, but on the way back from a pilgrimage to Mecca, he made Rasht his home after marrying the daughter of the local governor.[3] Kazembek received an extensive education. Leading clerics were hired by his father to instruct him in Arabic, logic, rhetoric, and jurisprudence, with the hope that he would also become a cleric.[4]

Kazembek grew up during the Russo-Iranian war of 1804–1813, which led to the Russian conquest of Derbent in 1806.[2][3] The Russians subsequently appointed Hajji Qasim Kazem-Beg as the principal qazi (a Muslim judge who performs both judicial and administrative tasks) of Derbent. Although Iran continued to lay formal claim to Derbent until the Treaty of Gulistan in 1813, the event decisively ended Iranian domination of the city.[5] After peace and order was established in Derbent in 1811, Kazembek and his mother rejoined Hajji Qasim Kazem-Beg at Derbent. A few years later, Hajji Qasim Kazem-Beg was found guilty of treason, likely due to his growing support among Iranian loyalists. As a result, the Russian governor-general of Georgia seized his belongings and banished him to Astrakhan as a prisoner.[6]

Conversation to Christianity from Islam

editAfter moving to Astrakhan in 1821 to live with his father, Kazembek quickly started going to the Scottish mission on a regular basis. Located on the western edge of the Grand Square, the Scottish mission was housed in one of the prominent buildings in the area. On Sundays, there was community prayers. There, several of the children had attained a high level of skill in Persian and Turkish, and distinguished themselves with their Persian calligraphy. While studying Christianity, Kazembek also started teaching the missionaries Tatar, Persian, and Arabic. During a previous visit to Derbent, Kazembek had encountered several missionaries, including William Glen, who was reportedly fluent in Persian. Glen's influence may have started Kazembek's interest in Christianity. Richard Knill, who served as pastor of the Independent Chapel in Saint Petersburg from 1821 to 1831, noted Kazembek's conversion in his journal on 15/22 May 1823. He wrote, "The Lord be praised for this trophy of his grace."[6]

Kazembek's father became distraught when he found out about his abandonment of Islam. Despite being confronted by the Iranian consul and a group of Iranians, Kazembek refused to abandon his Christian beliefs. When threatened by his father to delivered to the authorities in chains, Kazembek responded, "I cannot recant; my flesh would willingly become a Mahomedan, but my conscience will not allow me." Upon being told by his father that force and coercion decided all disputes regarding Islamic orthodoxy, Kazembek responded, "A sure proof that your religion is not of God, for he does not need such carnal weapons to decide matters of faith."[7]

As soon as the missionaries learned that Kazembek's father had beaten him brutally, put him in jail, and denied him food, they made a swift request to the governor of Astrakhan to save him. Soon after, the Russian civil authorities had Kazembek taken to the house of the Scottish mission, where the chief of police placed him in a secure location. In an attempt to claim Kazembek for the Armenian Apostolic Church, the Archbishop of Astrakhan tried to get involved in his Baptism. Muslims in the Russian Empire were only allowed to get baptised and tutored by Eastern Orthodox Church priests.[7]

The missionaries of the Scottish colony of Karass, worried that their efforts would be hindered by this law, notified the Archbishop of Astrakhan about the special privileges they had been granted by the Russian emperor Alexander I (r. 1801–1825). Eventually, the archbishop decided that the Russian emperor should make the final judgment about the rights of the Karass missionaries to train and baptize non-Orthodox converts. In a Persian-language letter to Alexander I, Kazembek pleaded to be baptized by the Scottish missionaries who had played a crucial role in introducing him to Christianity. To present their concerns to the emperor, the missionaries submitted a formal request to Alexander Nikolaevich Golitsyn, the Minister of Religious Affairs.[7]

Parts of the journal of the missionaries showed the results of their interactions with other Iranians in Astrakhan, which motivated them seek official recognition of their rights. One instance involved an Iranian cleric named Rasul, who was hesitant to embrace Christianity because he was worried about the backlash from people he owed money to. Golitsyn’s reply confirmed that the Karass missionaries, according to the imperial charter's articles, had the authority to baptize those who were converted through their efforts.[8] Before being baptized, Kazembek publicly declared his Christian religion in July 1823. Glen, McPherson, and Ross performed his Presbyterian baptism, giving him the name Aleksandr upon his request. The sacrament was performed in English, Tatar, and Persian in the Astrakhan mission chapel in front of Scots, Iranians, Tatars, Russians, Armenians, English, French, and Germans. As a result, everyone in the congregation understood a portion of the ceremony.[9]

Kazembek's missionary request and initial employment at Astrakhan

editDue to his conversion to Christianity, Kazembek was required to join the Russian imperial service in either a military, civil, or commercial position. He was told this by the governor-general of Astrakhan, who was following orders from the Russian general Aleksey Yermolov. The conditions placed upon Kazembek also included a written assurance not to leave Astrakhan without police approval and a prohibition against participating in Christian missionary work. Wishing to propagate the teachings of Christianity among his fellow countrymen, Kazembek submitted a formal request to Alexander I seeking authorization to do so.[9]

The missionaries initially sent Kazembek's request to Golitsyn for Alexander I's review, but he refused due to the latters worsening health. Subsequently, they reached out to Princess Sofia Sergeievna Meshcherskaia, a close companion and spiritual advisor to Alexander I, known for her role in facilitating communication between the Emperor and the missionaries. She agreed to present the request when the timing was more favorable but noted that it was not advisable to do so at that moment.[9]

Regarding future employment proposals, the Scottish Edinburgh authorities recommended on 2 September 1823 that Kazembek should not receive financial support that would elevate his lifestyle above his usual standard. They were concerned that such a change could tempt other Iranians to convert for material reasons. Additionally, Kazembek needed further training before he could teach others to prevent any potential for pride. Kazembek's study of religious texts, English language and literature was approved by the Edinburgh directors on 6 March 1824. Given a relatively small allowance, he was to be housed with one of the missionaries.[10]

Many months later, the Edinburgh board later disapproved of the 1,500 rubles annual allowance for Kazembek, noting that an unmarried missionary's standard was 1,200 rubles. They questioned why a upcoming missionary should receive more than a fully qualified European missionary. Kazembek's allowance was thus adjusted to 1,200 rubles. In November 1824, concerns arose after it was found that wine was among Kazembek's expenses, leading to a regulation that he should only be given wine for health reasons to prevent any potential for misuse or scandal. By late 1824, the Russian government decided to remove Kazembek from missionary care, and he requested to join the College of Foreign Affairs in Saint Petersburg instead of military or commercial service. In April 1825, the Edinburgh directors agreed to support him if he could go to Saint Petersburg, but Kazembek was ultimately ordered to attend the College of Omsk in Siberia by 1 November 1825.[11]

Career at the Kazan University

editIn January 1826, Kazembek, on his journey from Astrakhan to Omsk, had to stop in Kazan to recover from an illness. He was able to stay with Karl Fuchs, who was the rector of the Kazan University. In October 1826, Kazembek was officially named to the university's faculty after Fuchs managed to persuade the Russian foreign minister Karl Nesselrode to relieve Kazembek from his duties in Omsk. At that time, Kazan was seeking a new instructor in Tatar, with Kazembek being chosen due to his knowledge and personality.[12]

Established in 1804, the Kazan University was the only Russian university in a city mostly populated by Muslims. Kazan was a city with a mix of Russian and Tatar inhabitants. Many of its residents were also Christian Tatar converts.[13] Kazembek started his career at the Kazan University around the same time as its superintendent Mikhail Magnitskii was replaced by Mikhail Musin-Pushkin, who was more open to Oriental studies. The latter had spent many years working with the Ministry of Education, and was a dedicated advocate for the study of the Orient. With a distinguished family background and an admirable service record from the Napoleonic Wars, he passionately advanced the field of orientology.[12]

It was not uncommon for Kazan to select a native Asian speaker for language instruction. Ibrahim Halfin, a grandson of the gymnasium master appointed by Russian empress Catherine the Great (r. 1762–1796), had served as Kazembek's predecessor in the role of Tatar instructor. The university later expanded its faculty to include other Tatars, Iranians (including Kazembek's brother), and even a Buryat. These early Asian academics largely avoided disadvantages during their careers, with discrimination first becoming more pronounced in the Russian academy under the assimilationist governments of Alexander III (r. 1881–1894) and Nicholas II (r. 1894–1917).[14]

Kazembek's scholarly achievements quickly earned him considerable acclaim among his contemporaries. By 1829, he had been selected as a corresponding member of the Royal British Asiatic Society, and in 1835, he received the same recognition from the Russian Academy of Sciences. Following these honors, prominent oriental research organizations in Paris, Berlin, and Boston also acknowledged his contributions. His professional journey at Kazan University progressed quickly, becoming the adjunct professor in 1830. By 1837, he had achieved the rank of full professor. When Franz Erdmann gradually stepped down from his role as professor of Arabic and Persian literature in 1845, Kazembek was elevated to this position, which was considered more prominent. That same year, Kazembek was also chosen by his colleagues to serve as the dean of his faculty.[15]

The early studies of Kazembek were centered on writings from the Orient. His edition of the Turkish historical chronicle The Seven Planets, or the History of the Khans of the Crimea in 1832 brought him his first professional recognition. The publication of his Turkish book grammar in 1839 led to him receiving the Demidov Prize, a significant honor from the Russian Academy of Sciences, which he would win four times. By 1848, he had completed a German edition that continued to serve as a major textbook in European institutions through the early 20th century.[16]

Kazembek also focused on Islamic jurisprudence due to his background in the field. To assist government officials in dealing with minorities who kept sticking to their own traditional laws, he translated important legal texts into Arabic. In addition to this, he wrote academic papers on the subject.[16]

Career at the University of Saint Petersburg and death

editIn 1849, Kazembek moved to the University of Saint Petersburg, where he was appointed as a professor of Persian.[1] As his administrative duties increased, Kazembek became less focused on his studies. Upon his arrival, a commission asked him to evaluate Islamic legal codes, while another government body assigned him the task of translating liturgical texts into Tatar.[16] He was appointed dean of the Faculty of Oriental Studies in 1855, and he founded the Department of Oriental History in 1863.[3] For medical reasons, he traveled to Germany in February 1869. From there, he went to France, London, and Oxford. He visited London in November.[17] He soon returned to Saint Petersburg, dying there on 27 November 1870. He was buried in the city's district Pavlovsk, where had probably stayed for some days before his death.[18] Due to the disorder caused by the Russian Revolution, his burial place became forgotten.[3]

He was the great-grandfather Mladorossi founder Alexander Kazembek.

Works

editKazembek's work inevitably generated controversy, despite his efforts to retain his academic integrity. While conservative Russians thought he was too tolerant of Islam, Tatar intellectuals mistrusted the involvement of a former Muslim into what they saw as their own affairs.[19]

While in Astrakhan, Kazembek authored a treatise in Arabic defending Christianity, in similar fashion to the early work of Mirza Mohammad Ibrahim in Iran prior to his move to Haileybury in England. Once Glen's printing press released Kazembek's treatise, it spread widely throughout Iran, prompting a written response from Reza of Tabriz. Kazembek later replied with a second treatise written in Persian.[20] In 1832, one of his early significant works was published in Kazan: an edition of the Al-Sab' al-sayyar ft ta'rlkh muluk Tatar ("The Seven Planets on the History of the Tartar Kings"), a Turkish history authored by Sayyid Muhammad Riza. This historical account covers the reigns of the rulers of the Crimean Khanate, from Meñli I Giray (1466) to Meñli II Giray (1724).[21]

In 1841, Kazembek prepared an Arabic edition of the Mukhtasar al-Wiqaya, an essential guide in Islamic jurisprudence for Tatars and other Turkic groups in Russia. Instead of submitting his paper on Islamic law to the Russian Ministry of Education's journal, he chose to publish it in the Paris-based Journal Asiatique in 1842, due to concerns about his mostly positive analysis of Islamic jurisprudence getting criticized by conservative Russian officials.[16]

In a way that precedes the work of later Orientalists, Kazembek was particularly interested in pre-Islamic Iranian literature and the origins of the Persian epic poem Shahnameh. The contributions made by Kazembek to this topic, such as his 1848 work Mifologiya persov po Firdosi and his unpublished work O yazyke i literature persov do islamizma, are considered by Rzaev to be in need of detailed examination. According to the British Iranologist David Bivar; "On the other hand, his attempts to find parallels between ancient Greek and Iranian legends, though by no means wholly lacking in interest, might seem controversial or even dilettante today."[17]

According to Bivar, Kazembek's Obshchaya gramma tika Turetsko-tatarskago yazyka ("Comprehensive grammar of the Turko-Tartar language") published at Kazan in 1846 is most likely considered his most important work. This work was quickly translated into German by T. Zenker, who published it as Allgemeine Grammatik der turkisch-tatarischen Sprache at Leipzig in 1848. The German translation continues to serve as an important source for Western scholars specializing in Turkic studies.[17]

Bivar, however, considers Kazembek's most important work to be his edition of the Derbend-nama, a history of Derbent, which was published at Saint Petersburg in 1851. The work has a Turkish text alongside English translation and commentary.[17]

Kazembek's other works included;[22]

- A Russian translation of the Persian poem Gulistan by Saadi Shirazi, published in the Kazan University in 1829.

- O vzyatii Astrakhana v 1660 godu ("The capture of Astrakhan in the year 1660"), published in the Kazan University in 1835.

- Note critique sur un passage de l'histoire de l'Empire ottoman par M. de Hammer, published in the Journal Asiatique in 1835.

- Observations de Mirza Alexandre Kazem-Beg, professeur de langues ori entales a l'Universite de Casan, sur le Chapitre inconnu du Coran, publie et traduit par M. Garcin de Tassy, published in the Journal Asiatique in 1843.

- Muhammadiya, an edition of the poetical work of Yazidjizade Muhammad Effendi, which plays an important role in 15th-century Turkish Sufi literature. Published in the Kazan University in 1845.

- Thabat al-'ajizin ("The support of the helpless"), a poem in the Chagatai language, published in the Kazan University in 1847.

- Yarlyk khana zolotoi ordy Tokhtamysh k pol'skomu korolyu Yagailu, 1392-1393 ("The letter of Tokhtamish, Khan of the Golden Horde, to the Polish King Yagailu, in 1392-93"), published in the Kazan University in 1850. Kazembek's was the first person to decipher this document, written in the Old Uyghur alphabet. Previous orientalists had been unable to do this.

- Notice sur la marche et le progres de la jurisprudence parmi les sectes orthodoxes musulmanes, Journal Asiatique, xv, 1850, 158-214

Personality and appearance

editKazembek proudly displayed his Iranian heritage while maintaining a carefully liberal view in both his academic and political life. Wearing multicolored robes and a silk turban, Kazembek strolled through Saint Petersburg's streets, attracting attention from people. During the Crimean War, Kazembek showed no feelings of regret when his traditional eastern clothing was criticized as a treasonous provocation by the newspapers in Saint Petersburg. He preferred to be addressed as Mirza Aleksandr Kasimovich, a name which was a fusion of his Iranian title Mirza with the traditional Russian given name and patronymic, adhering to local customs.[4]

Kazembek's proficiency in Russian significantly enhanced his appeal as an educator, setting him apart from his German predecessors at Kazan. According to one of his former students; "I wasn't so much interested in the Tatar language as in Prof. Aleksandr Kasimovich Kazem-Bek. When I occasionally encountered him on the street, I very much enjoyed seeing the lively figure in his unusual garb and listening to his speech." Kazembek, despite his own assertions of solitude and reserve during his initial university years, was favored by his peers. Outside of school life, he was well-regarded. His presence was highly valued at social gatherings, particularly when notable guests visited. Russian emperor Nicholas I (r. 1825–1855) noticed Kazembek in particular in 1836 when on a tour of the city, stopping for a long talk.[23]

Legacy and assessment

editKazembek gained recognition for his Islamic-related works. He was one of the earliest authors in Russia to publish works on Islam in Iran.[24] The Iranian shah Naser al-Din Shah (r. 1848–1896) honored Kazembek with the Order of the Lion and the Sun in 1855 for his scholarly work on the Quran.[25]

According to Bivar; "With Kazem-Beg's lifelong attachment equally to English-speaking, and to Russian culture, and his combined proficiency in Persian and Turkish studies, a quality which he shared with both Bartol'd and Minorsky, the Persian deserves recognition as an intellectual forerunner not only of the distinguished Leningrad/St. Petersburg Iranian School, but also of that in London."[18]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Russian: Алекса́ндр Каси́мович Казембе́к or Казем-Бек

Azerbaijani: میرزا کاظمبک

Persian: میرزا کاظم بیگ Mirzâ Kâzem Beg

References

edit- ^ a b Bivar 1994, p. 284.

- ^ a b c Flynn 2017, p. 442.

- ^ a b c d e Jorati 2018.

- ^ a b Schimmelpenninck van der Oye 2010, p. 101.

- ^ Flynn 2017, pp. 442–443.

- ^ a b Flynn 2017, p. 443.

- ^ a b c Flynn 2017, p. 444.

- ^ Flynn 2017, pp. 444–445.

- ^ a b c Flynn 2017, p. 445.

- ^ Flynn 2017, p. 446.

- ^ Flynn 2017, p. 447.

- ^ a b Schimmelpenninck van der Oye 2010, p. 103.

- ^ Flynn 2017, p. 448.

- ^ Schimmelpenninck van der Oye 2010, p. 104.

- ^ Schimmelpenninck van der Oye 2010, pp. 104–105.

- ^ a b c d Schimmelpenninck van der Oye 2010, p. 105.

- ^ a b c d Bivar 1994, p. 297.

- ^ a b Bivar 1994, p. 298.

- ^ Schimmelpenninck van der Oye 2010, p. 107.

- ^ Green 2015, p. 127.

- ^ Bivar 1994, p. 296.

- ^ Bivar 1994, pp. 300–301.

- ^ Schimmelpenninck van der Oye 2010, p. 106.

- ^ Mikoulski 1997, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Khismatulin 2015, pp. 664–665.

Sources

edit- Bivar, A.D.H. (1994). "The Portraits and career of Mohammed Ali, son of Kazem-Beg: Scottish missionaries and Russian orientalism". Bulletin of the School of Oriental & African Studies. 57 (2). Cambridge University Press: 283–302. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00024861.

- Flynn, Thomas O. (2017). "Scottish and Jesuit Missionaries in the North Caucasus and the Imperial Russian Dominions: Karass, Astrakhan, Mozdok, Orenburg, the Crimea and Odessa (1805–30s)". The Western Christian Presence in the Russias and Qājār Persia, c.1760–c.1870. Brill. pp. 326–474. ISBN 978-9004163997.

- Jorati, Hadi (2018). "Alexander Kazembeg". In Thomas, D. (ed.). Christian-Muslim Relations. A Bibliographical History Volume 20. Iran, Afghanistan and the Caucasus (1800-1914). Brill. doi:10.1163/2451-9537_cmrii_COM_33220.

- Green, Nile (2015). Terrains of Exchange: Religious Economies of Global Islam. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0190222536.

- Khismatulin, Alexey (2015). "The Origins of Iranian Studies in Russia (Nineteenth to the Beginning of the Twentieth Century)". Iranian Studies. 48 (5). Cambridge University Press: 663–673. doi:10.1080/00210862.2015.1058635. JSTOR 24483012. (registration required)

- Mikoulski, Dimitri (1997). "The Study of Islam in Russia and the Former Soviet Union: An Overview". In Nanji, Azim (ed.). Mapping Islamic Studies: Genealogy, Continuity and Change. De Gruyter. pp. 95–107. ISBN 978-3-11-081168-1.

- Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, David (2010). Russian Orientalism: Asia in the Russian Mind from Peter the Great to the Emigration. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300110630.