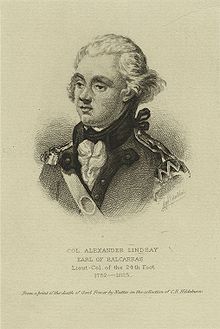

Alexander Lindsay, 6th Earl of Balcarres

General Alexander Lindsay, 6th Earl of Balcarres, 23rd Earl of Crawford (18 January 1752 – 27 March 1825), styled Lord Balniel until 1768, was a Scottish peer, military officer, politician and colonial administrator who served as the governor of Jamaica from 1795 to 1801.

The Earl of Balcarres | |

|---|---|

| |

| Governor of Jamaica | |

| In office 1795–1801 | |

| Monarch | George III |

| Preceded by | Sir Adam Williamson |

| Succeeded by | Sir George Nugent |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 18 January 1752 |

| Died | 27 March 1825 (aged 73) |

| Spouse |

Elizabeth Bradshaigh Dalrymple

(m. 1780) |

| Relations | James Lindsay, 5th Earl of Balcarres (father) |

| Children | 5, including James, the 7th Earl |

| Military career | |

| Service | British Army |

| Rank | General |

| Commands | |

| Battles / wars | |

Early life

editHe was the son of James Lindsay, 5th Earl of Balcarres and Anne Dalrymple, daughter of Sir Robert Dalrymple.[2] He entered the army at the age of fifteen as an ensign, in the 53rd Regiment of Foot. After attending Eton College, he studied at the University of Göttingen for two years, and subsequently purchased a captaincy in the 42nd Highland Regiment in 1771. He saw action during the American Revolutionary War; in 1775, he was appointed a major of the 53rd, and he commanded the light infantry companies at the Battle of Saratoga (1777), and surrendered there with Burgoyne. He was released from captivity in 1779.

Around this time he founded the famous Haigh Ironworks with his partners, his brother Robert and James Corbett.

Marriage

editOn 1 June 1780, he married his first cousin, Elizabeth Bradshaigh Dalrymple, who had inherited Haigh Hall estate, in Haigh, Lancashire.[3] They had five children:

- Lady Elizabeth Keith Lindsay (died 1825), married Richard Edensor Heathcote, thus the second great-grandmother of Oswald Mosley[2]

- James Lindsay, 24th Earl of Crawford (1783–1869)

- Edwin Lindsay

- Charles Robert Lindsay (1784–1835)

- Lady Anne Lindsay (died 1846)

Career

editHe was subsequently promoted to the rank of colonel and made lieutenant-colonel commandant of the second 71st Regiment of Foot made up of the four additional or recruiting companies of the 71st Highlanders in Scotland.[4] He was chosen a representative peer for Scotland in 1784, and was re-elected through 1807, inclusive. On 27 August 1789, he was appointed colonel of the 63rd Regiment of Foot, and was promoted major-general in 1793.

Governor of Jamaica

editCommander of the forces in Jersey from 1793 to 1794, he was then appointed Governor of Jamaica. He was governor when the Second Maroon War broke out, and he mishandled the situation so badly that he allowed a minor dispute over land to mushroom into a costly conflict that lasted months.[5][6] In early 1795, worried at the prospect of an uprising, Balcarres sent representatives to Havana to purchase 100 Cuban bloodhounds, which in his words were "[a] breed which are used to hunt down runaway negroes". Arriving a few months later, the bloodhounds were successfully employed against Maroons and runaways for the duration of the conflict, though their use provoked heavy criticism from abolitionists and military officers in Britain.[7]

Balcarres underestimated the guerrilla fighting capabilities of the Jamaican Maroons, who had the better of the skirmishes with the soldiers under the command of the governor's generals. Eventually, one of his generals, George Walpole, persuaded the leader of the Maroons of Cudjoe's Town, Montague James, to surrender on condition they would not be deported. However, Balcarres reversed Walpole's promise and transported the Trelawny Maroons to Nova Scotia.[8]

In the aftermath of the Second Maroon War, Balcarres struggled to disperse the runaway community of Cuffee in the Cockpit Country in western Jamaica. Hundreds of runaway slaves secured their freedom by fighting alongside Trelawny Town in the Second Maroon War, and many of them joined Cuffee's community.[9]

He was promoted lieutenant-general in 1798, and resigned the governorship in 1801. On 25 September 1803, he was promoted to general.

Later life

editAfter his return from the American Revolution, he was introduced to Benedict Arnold, who had led several attacks on his position at Saratoga. Balcarres snubbed Arnold as a traitor, and a duel ensued, neither party being injured. After being maimed in an accident he retired to the family's second home at Haigh Hall, near Wigan. On his death, he was succeeded by his eldest son James, the 7th Earl. After James had successfully pressed his claim to the title of Earl of Crawford in 1848, the title was conferred posthumously on Alexander, even though he had not claimed it himself.

His younger son, Edwin Lindsay, an Indian army officer, was declared insane after refusing to fight in a duel and was sent to Papa Stour in the Shetland islands. He spent 26 years there as a prisoner before the Quaker preacher Catherine Watson arranged for his release in 1835.[10][11]

Memorial

editHis memorial, in the Crawford chapel of All Saints' Church, Wigan, reads:

"Alexander VIth Earl of Balcarres Lord Lindsay and Balneill born 18 Jan 1750 General in the army and Governor of Jersey and Jamaica during the revolutionary War succeeded as XXIIIth Earl of Crawford in 1808 died 25 March 1825 and lies buried in this chapel "Except the Lord build the house they labour in vain that build it".[12]

Notes

editReferences

edit- ^ Wister, Sarah (1994). Sally Wister's Journal: A True Narrative : Being a Quaker Maiden's Account of Her Experiences with Officers of the Continental Army, 1777-1778. Applewood Books. ISBN 978-1-55709-114-7.

- ^ a b Mosley, Charles, ed. (2003). Burke's Peerage, Baronetage & Knighthood (107 ed.). Burke’s Peerage & Gentry. p. 954. ISBN 0-9711966-2-1.

- ^ "Haigh Hall". Archived from the original on 3 January 2010. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- ^ Letter from War Office to Sir Guy Carleton, 30 April 1782, PRO 30/55/39, document 4519, page 1, National Archives, Kew, United Kingdom

- ^ R.C. Dallas, The History of the Maroons (London: T.N. Longman, 1803), Vol. 1, pp. 167–9.

- ^ George Wilson Bridges, The Annals of Jamaica (London: John Murray, 1828), Vol. II, p. 258.

- ^ Parry, Tyler D.; Yingling, Charlton W. (1 February 2020). "Slave Hounds and Abolition in the Americas". Past & Present (246): 69–108. doi:10.1093/pastj/gtz020. ISSN 0031-2746.

- ^ Mavis Campbell, The Maroons of Jamaica 1655-1796: a History of Resistance, Collaboration & Betrayal (Massachusetts: Bergin & Garvey, 1988), pp. 209–249.

- ^ Michael Sivapragasam (2019) "The Second Maroon War: Runaway Slaves fighting on the side of Trelawny Town", Slavery & Abolition, doi:10.1080/0144039X.2019.1662683.

- ^ "General Alexander Lindsay, 6th Earl of Balcarres" The Peerage.com. Retrieved 15 September 2007.

- ^ Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004) The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh. Canongate. Page 452.

- ^ "All Saints Parish Church in the Town of Wigan - Memorials inside the Church". Lancashire OnLine Parish Clerks. Retrieved 16 October 2010.