This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (May 2018) |

Alexander Vasilievich Nikitenko (Алекса́ндр Васи́льевич Никите́нко; 12 March 1804 – 21 July 1877) was a literary historian from the Russian Empire. A well-educated Ukrainian serf of Count Sheremetev who was granted freedom under pressure from Kondraty Ryleyev and other men of letters. He narrowly escaped persecution in the wake of the Decembrist Uprising and served as censor through much of Nicholas I's reign. He was also a literary historian, censor, Professor of Saint Petersburg University, and ordinary member of St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences. Nikitenko is notable for a very detailed diary that he kept from an early age. It appeared in print in 1888-92; an abridged English translation was published in 1975.

Aleksandr Nikitenko | |

|---|---|

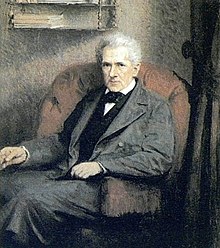

Portrait of Nikitenko by Ivan Kramskoi (1877) | |

| Born | Alexander Vasilievich Nikitenko March 12, 1804 |

| Died | July 21, 1877 (aged 74) Moscow, Moscow Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Nationality | Russian Empire |

| Education | Doctor of Philosophy (1828) |

| Occupation(s) | Author, censor |

| Employer | Saint Petersburg University |

Biography

editAlexander Nikitenko was born a serf, property of Count Nikolai Sheremetev, stationed in Alekseevka Sloboda of the Biruchenskii uezd.

Nikitenko was born in 1804 or 1805; his father, who served as senior clerk in the estate office of Count Sheremetev, was educated at the level above that of his peers and suffered from harassment by superiors for serfs' interests. Nikitenko's childhood was not favorable for good upbringing. He received his initial education at Voronezh Uezd School, but could not further advance his studies because as a serf, he would not be admitted to a Gymnasium. The young man was devastated and contemplated suicide for several years.

In 1822, in Ostrogozhsk, where Nikitenko was scratching a living by giving private lessons, the Russian Biblical Society opened a local chapter, and Nikitenko was elected secretary. His speech at the official meeting in 1824 was noticed, and Prince A. N. Golitsyn, The President of the Society and Minister of National Education, was made aware of it. Soon, with the assistance of V. A. Zhukovsky and K. F. Ryleev, Nikitenko was granted affranchisement.

At Ryleev's recommendation, Nikitenko settled in the household of E. P. Obolensky, a future Decembrist, who put him in charge of educating his younger brother. In 1825, Nikitenko was matriculated in The Imperial Saint-Petersburg University. He narrowly escaped prosecution for associating with the Decembrists, but was able to finish the course and graduate with a degree of Candidate from the Department of History and Philosophy. Nikitenko then was offered a course at the Professorial Institute at Dorpat University, but he declined, unwilling to commit to the required subsequent 14-year professorial contract with the university.[1]

In 1826, he published his first article "On Overcoming the Misfortunes" in the "Syn Otechectva"("Son of the Fatherland"), for which he was given much consideration by Grech and Bulgarin, and won the trust of the District Superintendent of Education K. M. Borozdin, who hired him as his secretary. At his request, Nikitenko compiled a commentary for the new Censorship Code (1828).

From 1830 he was Political Economy lecturer in Saint Petersburg University. After failing to become a faculty member in the Department of Natural Law and Political Economy, he joined the department of Russian Philology in 1832 as adjunct faculty, and in 1834 became professor.

In 1833, Nikitenko was appointed Censor and was soon arrested for eight days in the military jail for releasing Victor Hugo's poem «Enfant, si j'étais roi» (translated by M. Delarue).

Nikitenko also served as lecturer of Russian Philology in Roman Catholic Theological Academy. In 1839-41 he was editor of the literary journal "Syn Otechectva"("Son of the Fatherland"), in 1847-48 "Sovremennik" (The Contemporary)

In 1837, he was conferred the degree of Doctor of Philosophy for his dissertation "On Creative Power of Poetry or Poetic Genius".[2] In 1853, Nikitenko was elected Corresponding Member of the Department of Russian Language and Philology of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences, and in 1855 he was elected Ordinary Academician in the same department.

In his role as censor, Nikitenko regularly wrote the code projects, instructions or commentaries to them in Martinist, as defined by Bulgarin, that is, in a relatively liberal spirit.

In 1842, Nikitenko was arrested for one night in the military jail for allowing the short novel "A Governess" by P. Ephebovsky, containing mockery of the Feldjagers.

Nikitenko enthusiastically welcomed the Great Reforms (political, judicial and economic reforms of Alexander II), describing himself as a "moderate progressist".

In 1859, Nikitenko became a member of the Private Committee on Censorship, where he ardently promoted the importance of literature, and petitioned for the conversion of the extraordinary and temporary status of the institution of censorship into a permanent and regular one, as "Chief Censorship Agency" under the Minister of National Education. He had partially succeeded, but he received an unexpected blow when the Agency was transferred into the structure of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (charged in particular with police and state security tasks).

In the late 1850s, Nikitenko served as editor of the Journal of the Ministry of Education; he sat on and from 1857 chaired the Committee on Theater. Nikitenko completed his service in the rank of Privy Councillor.

His best known works on literary history include "Speech on Criticism" (SPb., 1842) and "Essays on the history of Russian Literature. Introduction" (SPb.,1845). As characterized by the Soviet Historical Encyclopedia, his "scientific work and criticism were eclectic, lacked clear concept and did not gain much success."

The famous diary of Nikitenko was published in 1889-92 and was translated into a few foreign languages in the course of the 20th century. The special 1893 edition also contained his memoir «Моя повесть о самом себе (The tale about myself). There were many subsequent editions, but none during the Soviet period. In 2004, the diary was published in three volumes Dnevnik[3]

Writings

edit- The Diary of a Russian Censor. University of Massachusetts Press. 1975. (Trans. by Helen Saltz Jacobson)

- Up from Serfdom. My Childhood and Youth in Russia, 1804-1824. Yale University Press. 2002. (Trans. by Helen Saltz Jacobson)

Notes

edit- ^ "October 16, 1827" / Diary. — Vol. 1.

- ^ Императорский С.-Петербургский университет 1870, p. XII.

- ^ "Дневник". WorldCat.

Sources

edit- Никитенко, Александр Васильевич. (in Russian) – via Wikisource. //Русский биографический словарь : в 25 томах. — СПб.—М., 1896—1918. (in Russian) – via Wikisource.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Ч. Ветринский, «Два русских общественных типа» (Никитенко и И. С. Аксаков, «Новое Слово», №№ 7—8, 1894);

- M. A. Протопопов, «Из истории нашей общественности» («Записки» и «Дневник» Никитенко, «Русская Мысль», №№ 6—7, 1893);

- К. Н. Медведский, «Повесть честного гражданина» (по поводу «Дневника» Никитенко, «Наблюдатель», №№ 3—4, 1893).

- Глазычев В. Горчащий привкус ума

- Чешихин В. Е. [in Russian]. (in Russian) – via Wikisource.

- В. В. Григорьев (1870). Императорский С.-Петербургский университет в течение первых 50 лет его существования (PDF) (Типография В. Безобразова и Комп. ed.). СПб.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

External links

edit- A.V. Nikitenko profile page on the official site of Russian Academy of Sciences.

- Зотов В.Р. Либеральный цензор и профессор-пессимист. (Биографический очерк) // Исторический вестник, 1893. – Т. 54. - № 10. – С. 194-210.

- «Дневник. Том 1». Alexander Vasilievich Nikitenko. Diary, vol. 1

- «Дневник. Том 2». Alexander Vasilievich Nikitenko. Diary, vol. 2

- «Дневник. Том 3». Alexander Vasilievich Nikitenko. Diary, vol. 3

- Media related to Alexander Nikitenko at Wikimedia Commons