In mathematics, projective geometry is the study of geometric properties that are invariant with respect to projective transformations. This means that, compared to elementary Euclidean geometry, projective geometry has a different setting (projective space) and a selective set of basic geometric concepts. The basic intuitions are that projective space has more points than Euclidean space, for a given dimension, and that geometric transformations are permitted that transform the extra points (called "points at infinity") to Euclidean points, and vice versa.

Properties meaningful for projective geometry are respected by this new idea of transformation, which is more radical in its effects than can be expressed by a transformation matrix and translations (the affine transformations). The first issue for geometers is what kind of geometry is adequate for a novel situation. Unlike in Euclidean geometry, the concept of an angle does not apply in projective geometry, because no measure of angles is invariant with respect to projective transformations, as is seen in perspective drawing from a changing perspective. One source for projective geometry was indeed the theory of perspective. Another difference from elementary geometry is the way in which parallel lines can be said to meet in a point at infinity, once the concept is translated into projective geometry's terms. Again this notion has an intuitive basis, such as railway tracks meeting at the horizon in a perspective drawing. See Projective plane for the basics of projective geometry in two dimensions.

While the ideas were available earlier, projective geometry was mainly a development of the 19th century. This included the theory of complex projective space, the coordinates used (homogeneous coordinates) being complex numbers. Several major types of more abstract mathematics (including invariant theory, the Italian school of algebraic geometry, and Felix Klein's Erlangen programme resulting in the study of the classical groups) were motivated by projective geometry. It was also a subject with many practitioners for its own sake, as synthetic geometry. Another topic that developed from axiomatic studies of projective geometry is finite geometry.

The topic of projective geometry is itself now divided into many research subtopics, two examples of which are projective algebraic geometry (the study of projective varieties) and projective differential geometry (the study of differential invariants of the projective transformations).

Overview

editProjective geometry is an elementary non-metrical form of geometry, meaning that it does not support any concept of distance. In two dimensions it begins with the study of configurations of points and lines. That there is indeed some geometric interest in this sparse setting was first established by Desargues and others in their exploration of the principles of perspective art.[1] In higher dimensional spaces there are considered hyperplanes (that always meet), and other linear subspaces, which exhibit the principle of duality. The simplest illustration of duality is in the projective plane, where the statements "two distinct points determine a unique line" (i.e. the line through them) and "two distinct lines determine a unique point" (i.e. their point of intersection) show the same structure as propositions. Projective geometry can also be seen as a geometry of constructions with a straight-edge alone, excluding compass constructions, common in straightedge and compass constructions.[2] As such, there are no circles, no angles, no measurements, no parallels, and no concept of intermediacy (or "betweenness").[3] It was realised that the theorems that do apply to projective geometry are simpler statements. For example, the different conic sections are all equivalent in (complex) projective geometry, and some theorems about circles can be considered as special cases of these general theorems.

During the early 19th century the work of Jean-Victor Poncelet, Lazare Carnot and others established projective geometry as an independent field of mathematics.[3] Its rigorous foundations were addressed by Karl von Staudt and perfected by Italians Giuseppe Peano, Mario Pieri, Alessandro Padoa and Gino Fano during the late 19th century.[4] Projective geometry, like affine and Euclidean geometry, can also be developed from the Erlangen program of Felix Klein; projective geometry is characterized by invariants under transformations of the projective group.

After much work on the very large number of theorems in the subject, therefore, the basics of projective geometry became understood. The incidence structure and the cross-ratio are fundamental invariants under projective transformations. Projective geometry can be modeled by the affine plane (or affine space) plus a line (hyperplane) "at infinity" and then treating that line (or hyperplane) as "ordinary".[5] An algebraic model for doing projective geometry in the style of analytic geometry is given by homogeneous coordinates.[6][7] On the other hand, axiomatic studies revealed the existence of non-Desarguesian planes, examples to show that the axioms of incidence can be modelled (in two dimensions only) by structures not accessible to reasoning through homogeneous coordinate systems.

In a foundational sense, projective geometry and ordered geometry are elementary since they each involve a minimal set of axioms and either can be used as the foundation for affine and Euclidean geometry.[8][9] Projective geometry is not "ordered"[3] and so it is a distinct foundation for geometry.

Description

editThis section may lack focus or may be about more than one topic. In particular, "Description" is either vague or too broad.. (March 2023) |

Projective geometry is less restrictive than either Euclidean geometry or affine geometry. It is an intrinsically non-metrical geometry, meaning that facts are independent of any metric structure. Under the projective transformations, the incidence structure and the relation of projective harmonic conjugates are preserved. A projective range is the one-dimensional foundation. Projective geometry formalizes one of the central principles of perspective art: that parallel lines meet at infinity, and therefore are drawn that way. In essence, a projective geometry may be thought of as an extension of Euclidean geometry in which the "direction" of each line is subsumed within the line as an extra "point", and in which a "horizon" of directions corresponding to coplanar lines is regarded as a "line". Thus, two parallel lines meet on a horizon line by virtue of their incorporating the same direction.

Idealized directions are referred to as points at infinity, while idealized horizons are referred to as lines at infinity. In turn, all these lines lie in the plane at infinity. However, infinity is a metric concept, so a purely projective geometry does not single out any points, lines or planes in this regard—those at infinity are treated just like any others.

Because a Euclidean geometry is contained within a projective geometry—with projective geometry having a simpler foundation—general results in Euclidean geometry may be derived in a more transparent manner, where separate but similar theorems of Euclidean geometry may be handled collectively within the framework of projective geometry. For example, parallel and nonparallel lines need not be treated as separate cases; rather an arbitrary projective plane is singled out as the ideal plane and located "at infinity" using homogeneous coordinates.

Additional properties of fundamental importance include Desargues' Theorem and the Theorem of Pappus. In projective spaces of dimension 3 or greater there is a construction that allows one to prove Desargues' Theorem. But for dimension 2, it must be separately postulated.

Using Desargues' Theorem, combined with the other axioms, it is possible to define the basic operations of arithmetic, geometrically. The resulting operations satisfy the axioms of a field – except that the commutativity of multiplication requires Pappus's hexagon theorem. As a result, the points of each line are in one-to-one correspondence with a given field, F, supplemented by an additional element, ∞, such that r ⋅ ∞ = ∞, −∞ = ∞, r + ∞ = ∞, r / 0 = ∞, r / ∞ = 0, ∞ − r = r − ∞ = ∞, except that 0 / 0, ∞ / ∞, ∞ + ∞, ∞ − ∞, 0 ⋅ ∞ and ∞ ⋅ 0 remain undefined.

Projective geometry also includes a full theory of conic sections, a subject also extensively developed in Euclidean geometry. There are advantages to being able to think of a hyperbola and an ellipse as distinguished only by the way the hyperbola lies across the line at infinity; and that a parabola is distinguished only by being tangent to the same line. The whole family of circles can be considered as conics passing through two given points on the line at infinity — at the cost of requiring complex coordinates. Since coordinates are not "synthetic", one replaces them by fixing a line and two points on it, and considering the linear system of all conics passing through those points as the basic object of study. This method proved very attractive to talented geometers, and the topic was studied thoroughly. An example of this method is the multi-volume treatise by H. F. Baker.

History

editThe first geometrical properties of a projective nature were discovered during the 3rd century by Pappus of Alexandria.[3] Filippo Brunelleschi (1404–1472) started investigating the geometry of perspective during 1425[10] (see Perspective (graphical) § History for a more thorough discussion of the work in the fine arts that motivated much of the development of projective geometry). Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) and Girard Desargues (1591–1661) independently developed the concept of the "point at infinity".[11] Desargues developed an alternative way of constructing perspective drawings by generalizing the use of vanishing points to include the case when these are infinitely far away. He made Euclidean geometry, where parallel lines are truly parallel, into a special case of an all-encompassing geometric system. Desargues's study on conic sections drew the attention of 16-year-old Blaise Pascal and helped him formulate Pascal's theorem. The works of Gaspard Monge at the end of 18th and beginning of 19th century were important for the subsequent development of projective geometry. The work of Desargues was ignored until Michel Chasles chanced upon a handwritten copy during 1845. Meanwhile, Jean-Victor Poncelet had published the foundational treatise on projective geometry during 1822. Poncelet examined the projective properties of objects (those invariant under central projection) and, by basing his theory on the concrete pole and polar relation with respect to a circle, established a relationship between metric and projective properties. The non-Euclidean geometries discovered soon thereafter were eventually demonstrated to have models, such as the Klein model of hyperbolic space, relating to projective geometry.

In 1855 A. F. Möbius wrote an article about permutations, now called Möbius transformations, of generalised circles in the complex plane. These transformations represent projectivities of the complex projective line. In the study of lines in space, Julius Plücker used homogeneous coordinates in his description, and the set of lines was viewed on the Klein quadric, one of the early contributions of projective geometry to a new field called algebraic geometry, an offshoot of analytic geometry with projective ideas.

Projective geometry was instrumental in the validation of speculations of Lobachevski and Bolyai concerning hyperbolic geometry by providing models for the hyperbolic plane:[12] for example, the Poincaré disc model where generalised circles perpendicular to the unit circle correspond to "hyperbolic lines" (geodesics), and the "translations" of this model are described by Möbius transformations that map the unit disc to itself. The distance between points is given by a Cayley–Klein metric, known to be invariant under the translations since it depends on cross-ratio, a key projective invariant. The translations are described variously as isometries in metric space theory, as linear fractional transformations formally, and as projective linear transformations of the projective linear group, in this case SU(1, 1).

The work of Poncelet, Jakob Steiner and others was not intended to extend analytic geometry. Techniques were supposed to be synthetic: in effect projective space as now understood was to be introduced axiomatically. As a result, reformulating early work in projective geometry so that it satisfies current standards of rigor can be somewhat difficult. Even in the case of the projective plane alone, the axiomatic approach can result in models not describable via linear algebra.

This period in geometry was overtaken by research on the general algebraic curve by Clebsch, Riemann, Max Noether and others, which stretched existing techniques, and then by invariant theory. Towards the end of the century, the Italian school of algebraic geometry (Enriques, Segre, Severi) broke out of the traditional subject matter into an area demanding deeper techniques.

During the later part of the 19th century, the detailed study of projective geometry became less fashionable, although the literature is voluminous. Some important work was done in enumerative geometry in particular, by Schubert, that is now considered as anticipating the theory of Chern classes, taken as representing the algebraic topology of Grassmannians.

Projective geometry later proved key to Paul Dirac's invention of quantum mechanics. At a foundational level, the discovery that quantum measurements could fail to commute had disturbed and dissuaded Heisenberg, but past study of projective planes over noncommutative rings had likely desensitized Dirac. In more advanced work, Dirac used extensive drawings in projective geometry to understand the intuitive meaning of his equations, before writing up his work in an exclusively algebraic formalism.[13]

Classification

editThere are many projective geometries, which may be divided into discrete and continuous: a discrete geometry comprises a set of points, which may or may not be finite in number, while a continuous geometry has infinitely many points with no gaps in between.

The only projective geometry of dimension 0 is a single point. A projective geometry of dimension 1 consists of a single line containing at least 3 points. The geometric construction of arithmetic operations cannot be performed in either of these cases. For dimension 2, there is a rich structure in virtue of the absence of Desargues' Theorem.

The smallest 2-dimensional projective geometry (that with the fewest points) is the Fano plane, which has 3 points on every line, with 7 points and 7 lines in all, having the following collinearities:

- [ABC]

- [ADE]

- [AFG]

- [BDG]

- [BEF]

- [CDF]

- [CEG]

with homogeneous coordinates A = (0,0,1), B = (0,1,1), C = (0,1,0), D = (1,0,1), E = (1,0,0), F = (1,1,1), G = (1,1,0), or, in affine coordinates, A = (0,0), B = (0,1), C = (∞), D = (1,0), E = (0), F = (1,1)and G = (1). The affine coordinates in a Desarguesian plane for the points designated to be the points at infinity (in this example: C, E and G) can be defined in several other ways.

In standard notation, a finite projective geometry is written PG(a, b) where:

- a is the projective (or geometric) dimension, and

- b is one less than the number of points on a line (called the order of the geometry).

Thus, the example having only 7 points is written PG(2, 2).

The term "projective geometry" is used sometimes to indicate the generalised underlying abstract geometry, and sometimes to indicate a particular geometry of wide interest, such as the metric geometry of flat space which we analyse through the use of homogeneous coordinates, and in which Euclidean geometry may be embedded (hence its name, Extended Euclidean plane).

The fundamental property that singles out all projective geometries is the elliptic incidence property that any two distinct lines L and M in the projective plane intersect at exactly one point P. The special case in analytic geometry of parallel lines is subsumed in the smoother form of a line at infinity on which P lies. The line at infinity is thus a line like any other in the theory: it is in no way special or distinguished. (In the later spirit of the Erlangen programme one could point to the way the group of transformations can move any line to the line at infinity).

The parallel properties of elliptic, Euclidean and hyperbolic geometries contrast as follows:

- Given a line l and a point P not on the line,

- Elliptic

- there exists no line through P that does not meet l

- Euclidean

- there exists exactly one line through P that does not meet l

- Hyperbolic

- there exists more than one line through P that does not meet l

The parallel property of elliptic geometry is the key idea that leads to the principle of projective duality, possibly the most important property that all projective geometries have in common.

Duality

editIn 1825, Joseph Gergonne noted the principle of duality characterizing projective plane geometry: given any theorem or definition of that geometry, substituting point for line, lie on for pass through, collinear for concurrent, intersection for join, or vice versa, results in another theorem or valid definition, the "dual" of the first. Similarly in 3 dimensions, the duality relation holds between points and planes, allowing any theorem to be transformed by swapping point and plane, is contained by and contains. More generally, for projective spaces of dimension N, there is a duality between the subspaces of dimension R and dimension N − R − 1. For N = 2, this specializes to the most commonly known form of duality—that between points and lines. The duality principle was also discovered independently by Jean-Victor Poncelet.

To establish duality only requires establishing theorems which are the dual versions of the axioms for the dimension in question. Thus, for 3-dimensional spaces, one needs to show that (1*) every point lies in 3 distinct planes, (2*) every two planes intersect in a unique line and a dual version of (3*) to the effect: if the intersection of plane P and Q is coplanar with the intersection of plane R and S, then so are the respective intersections of planes P and R, Q and S (assuming planes P and S are distinct from Q and R).

In practice, the principle of duality allows us to set up a dual correspondence between two geometric constructions. The most famous of these is the polarity or reciprocity of two figures in a conic curve (in 2 dimensions) or a quadric surface (in 3 dimensions). A commonplace example is found in the reciprocation of a symmetrical polyhedron in a concentric sphere to obtain the dual polyhedron.

Another example is Brianchon's theorem, the dual of the already mentioned Pascal's theorem, and one of whose proofs simply consists of applying the principle of duality to Pascal's. Here are comparative statements of these two theorems (in both cases within the framework of the projective plane):

- Pascal: If all six vertices of a hexagon lie on a conic, then the intersections of its opposite sides (regarded as full lines, since in the projective plane there is no such thing as a "line segment") are three collinear points. The line joining them is then called the Pascal line of the hexagon.

- Brianchon: If all six sides of a hexagon are tangent to a conic, then its diagonals (i.e. the lines joining opposite vertices) are three concurrent lines. Their point of intersection is then called the Brianchon point of the hexagon.

- (If the conic degenerates into two straight lines, Pascal's becomes Pappus's theorem, which has no interesting dual, since the Brianchon point trivially becomes the two lines' intersection point.)

Axioms of projective geometry

editAny given geometry may be deduced from an appropriate set of axioms. Projective geometries are characterised by the "elliptic parallel" axiom, that any two planes always meet in just one line, or in the plane, any two lines always meet in just one point. In other words, there are no such things as parallel lines or planes in projective geometry.

Many alternative sets of axioms for projective geometry have been proposed (see for example Coxeter 2003, Hilbert & Cohn-Vossen 1999, Greenberg 1980).

Whitehead's axioms

editThese axioms are based on Whitehead, "The Axioms of Projective Geometry". There are two types, points and lines, and one "incidence" relation between points and lines. The three axioms are:

- G1: Every line contains at least 3 points

- G2: Every two distinct points, A and B, lie on a unique line, AB.

- G3: If lines AB and CD intersect, then so do lines AC and BD (where it is assumed that A and D are distinct from B and C).

The reason each line is assumed to contain at least 3 points is to eliminate some degenerate cases. The spaces satisfying these three axioms either have at most one line, or are projective spaces of some dimension over a division ring, or are non-Desarguesian planes.

Additional axioms

editOne can add further axioms restricting the dimension or the coordinate ring. For example, Coxeter's Projective Geometry,[14] references Veblen[15] in the three axioms above, together with a further 5 axioms that make the dimension 3 and the coordinate ring a commutative field of characteristic not 2.

Axioms using a ternary relation

editOne can pursue axiomatization by postulating a ternary relation, [ABC] to denote when three points (not all necessarily distinct) are collinear. An axiomatization may be written down in terms of this relation as well:

- C0: [ABA]

- C1: If A and B are distinct points such that [ABC] and [ABD] then [BDC]

- C2: If A and B are distinct points then there exists a third distinct point C such that [ABC]

- C3: If A and C are distinct points, B and D are distinct points, with [BCE], [ADE] but not [ABE] then there is a point F such that [ACF] and [BDF].

For two distinct points, A and B, the line AB is defined as consisting of all points C for which [ABC]. The axioms C0 and C1 then provide a formalization of G2; C2 for G1 and C3 for G3.

The concept of line generalizes to planes and higher-dimensional subspaces. A subspace, AB...XY may thus be recursively defined in terms of the subspace AB...X as that containing all the points of all lines YZ, as Z ranges over AB...X. Collinearity then generalizes to the relation of "independence". A set {A, B, ..., Z} of points is independent, [AB...Z] if {A, B, ..., Z} is a minimal generating subset for the subspace AB...Z.

The projective axioms may be supplemented by further axioms postulating limits on the dimension of the space. The minimum dimension is determined by the existence of an independent set of the required size. For the lowest dimensions, the relevant conditions may be stated in equivalent form as follows. A projective space is of:

- (L1) at least dimension 0 if it has at least 1 point,

- (L2) at least dimension 1 if it has at least 2 distinct points (and therefore a line),

- (L3) at least dimension 2 if it has at least 3 non-collinear points (or two lines, or a line and a point not on the line),

- (L4) at least dimension 3 if it has at least 4 non-coplanar points.

The maximum dimension may also be determined in a similar fashion. For the lowest dimensions, they take on the following forms. A projective space is of:

- (M1) at most dimension 0 if it has no more than 1 point,

- (M2) at most dimension 1 if it has no more than 1 line,

- (M3) at most dimension 2 if it has no more than 1 plane,

and so on. It is a general theorem (a consequence of axiom (3)) that all coplanar lines intersect—the very principle that projective geometry was originally intended to embody. Therefore, property (M3) may be equivalently stated that all lines intersect one another.

It is generally assumed that projective spaces are of at least dimension 2. In some cases, if the focus is on projective planes, a variant of M3 may be postulated. The axioms of (Eves 1997: 111), for instance, include (1), (2), (L3) and (M3). Axiom (3) becomes vacuously true under (M3) and is therefore not needed in this context.

Axioms for projective planes

editIn incidence geometry, most authors[16] give a treatment that embraces the Fano plane PG(2, 2) as the smallest finite projective plane. An axiom system that achieves this is as follows:

- (P1) Any two distinct points lie on a line that is unique.

- (P2) Any two distinct lines meet at a point that is unique.

- (P3) There exist at least four points of which no three are collinear.

Coxeter's Introduction to Geometry[17] gives a list of five axioms for a more restrictive concept of a projective plane that is attributed to Bachmann, adding Pappus's theorem to the list of axioms above (which eliminates non-Desarguesian planes) and excluding projective planes over fields of characteristic 2 (those that do not satisfy Fano's axiom). The restricted planes given in this manner more closely resemble the real projective plane.

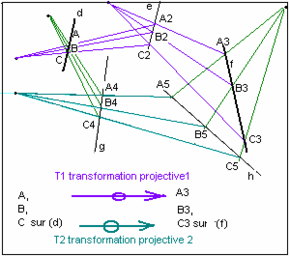

Perspectivity and projectivity

editGiven three non-collinear points, there are three lines connecting them, but with four points, no three collinear, there are six connecting lines and three additional "diagonal points" determined by their intersections. The science of projective geometry captures this surplus determined by four points through a quaternary relation and the projectivities which preserve the complete quadrangle configuration.

An harmonic quadruple of points on a line occurs when there is a complete quadrangle two of whose diagonal points are in the first and third position of the quadruple, and the other two positions are points on the lines joining two quadrangle points through the third diagonal point.[18]

A spatial perspectivity of a projective configuration in one plane yields such a configuration in another, and this applies to the configuration of the complete quadrangle. Thus harmonic quadruples are preserved by perspectivity. If one perspectivity follows another the configurations follow along. The composition of two perspectivities is no longer a perspectivity, but a projectivity.

While corresponding points of a perspectivity all converge at a point, this convergence is not true for a projectivity that is not a perspectivity. In projective geometry the intersection of lines formed by corresponding points of a projectivity in a plane are of particular interest. The set of such intersections is called a projective conic, and in acknowledgement of the work of Jakob Steiner, it is referred to as a Steiner conic.

Suppose a projectivity is formed by two perspectivities centered on points A and B, relating x to X by an intermediary p:

The projectivity is then Then given the projectivity the induced conic is

Given a conic C and a point P not on it, two distinct secant lines through P intersect C in four points. These four points determine a quadrangle of which P is a diagonal point. The line through the other two diagonal points is called the polar of P and P is the pole of this line.[19] Alternatively, the polar line of P is the set of projective harmonic conjugates of P on a variable secant line passing through P and C.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Ramanan 1997, p. 88.

- ^ Coxeter 2003, p. v.

- ^ a b c d Coxeter 1969, p. 229.

- ^ Coxeter 2003, p. 14.

- ^ Coxeter 1969, pp. 93, 261.

- ^ Coxeter 1969, pp. 234–238.

- ^ Coxeter 2003, pp. 111–132.

- ^ Coxeter 1969, pp. 175–262.

- ^ Coxeter 2003, pp. 102–110.

- ^ Coxeter 2003, p. 2.

- ^ Coxeter 2003, p. 3.

- ^ John Milnor (1982) Hyperbolic geometry: The first 150 years, Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society via Project Euclid

- ^ Farmelo, Graham (September 15, 2005). "Dirac's hidden geometry" (PDF). Essay. Nature. 437 (7057). Nature Publishing Group: 323. Bibcode:2005Natur.437..323F. doi:10.1038/437323a. PMID 16163331. S2CID 34940597.

- ^ Coxeter 2003, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Veblen & Young 1938, pp. 16, 18, 24, 45.

- ^ Bennett 1995, p. 4, Beutelspacher & Rosenbaum 1998, p. 8, Casse 2006, p. 29, Cederberg 2001, p. 9, Garner 1981, p. 7, Hughes & Piper 1973, p. 77, Mihalek 1972, p. 29, Polster 1998, p. 5 and Samuel 1988, p. 21 among the references given.

- ^ Coxeter 1969, pp. 229–234.

- ^ Halsted 1906, pp. 15, 16.

- ^ Halsted 1906, p. 25.

References

edit- Bachmann, F. (2013) [1959]. Aufbau der Geometrie aus dem Spiegelungsbegriff (2nd ed.). Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-642-65537-1.

- Baer, Reinhold (2005). Linear Algebra and Projective Geometry. Mineola NY: Dover. ISBN 0-486-44565-8.

- Bennett, M.K. (1995). Affine and Projective Geometry. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-11315-8.

- Beutelspacher, Albrecht; Rosenbaum, Ute (1998). Projective Geometry: From Foundations to Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-48277-1.

- Casse, Rey (2006). Projective Geometry: An Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-929886-6.

- Cederberg, Judith N. (2001). A Course in Modern Geometries. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-98972-2.

- Coxeter, H.S.M. (2013) [1993]. The Real Projective Plane (3rd ed.). Springer Verlag. ISBN 9781461227342.

- Coxeter, H.S.M. (2003). Projective Geometry (2nd ed.). Springer Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-40623-7.

- Coxeter, H.S.M. (1969). Introduction to Geometry. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-50458-0.

- Dembowski, Peter (1968). Finite Geometries. Ergebnisse der Mathematik und ihrer Grenzgebiete, Band 44. Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 3-540-61786-8. MR 0233275.

- Eves, Howard (2012) [1997]. Foundations and Fundamental Concepts of Mathematics (3rd ed.). Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-13220-4.

- Garner, Lynn E. (1981). An Outline of Projective Geometry. North Holland. ISBN 0-444-00423-8.

- Greenberg, M.J. (2008). Euclidean and Non-Euclidean Geometries: Development and History (4th ed.). W. H. Freeman. ISBN 978-1-4292-8133-1.

- Halsted, G. B. (1906). Synthetic Projective Geometry. New York Wiley.

- Hartley, Richard; Zisserman, Andrew (2003). Multiple view geometry in computer vision (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-54051-8.

- Hartshorne, Robin (2009). Foundations of Projective Geometry (2nd ed.). Ishi Press. ISBN 978-4-87187-837-1.

- Hartshorne, Robin (2013) [2000]. Geometry: Euclid and Beyond. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-22676-7.

- Hilbert, D.; Cohn-Vossen, S. (1999). Geometry and the Imagination (2nd ed.). American Mathematical Society. ISBN 978-0-8218-1998-2.

- Hughes, D.R.; Piper, F.C. (1973). Projective Planes. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-90044-3.

- Mihalek, R.J. (1972). Projective Geometry and Algebraic Structures. New York: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-495550-9.

- Polster, Burkard (1998). A Geometrical Picture Book. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-98437-2.

- Ramanan, S. (August 1997). "Projective geometry". Resonance. 2 (8). Springer India: 87–94. doi:10.1007/BF02835009. ISSN 0971-8044. S2CID 195303696.

- Samuel, Pierre (1988). Projective Geometry. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-96752-4.

- Santaló, Luis (1966) Geometría proyectiva, Editorial Universitaria de Buenos Aires

- Veblen, Oswald; Young, J. W. A. (1938). Projective Geometry. Boston: Ginn & Co. ISBN 978-1-4181-8285-4.

External links

edit- Projective Geometry for Machine Vision — tutorial by Joe Mundy and Andrew Zisserman.

- Notes based on Coxeter's The Real Projective Plane.

- Projective Geometry for Image Analysis — free tutorial by Roger Mohr and Bill Triggs.

- Projective Geometry. — free tutorial by Tom Davis.

- The Grassmann method in projective geometry A compilation of three notes by Cesare Burali-Forti on the application of exterior algebra to projective geometry

- C. Burali-Forti, "Introduction to Differential Geometry, following the method of H. Grassmann" (English translation of book)

- E. Kummer, "General theory of rectilinear ray systems" (English translation)

- M. Pasch, "On the focal surfaces of ray systems and the singularity surfaces of complexes" (English translation)