Ali Ahmed Karti (Arabic: علي أحمد كرتي; born 11 March or 27 October 1953) is a Sudanese politician and businessman. Karti served as Minister of Foreign Affairs of Sudan from 2010 to 2015. As of June 2021 he is the secretary general of the Sudanese Islamic Movement.

Ali Ahmed Karti | |

|---|---|

علي أحمد كرتي | |

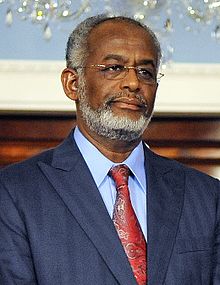

Ali Ahmed Karti in 2011 | |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 2010 – 7 June 2015 | |

| President | Omar al-Bashir |

| Preceded by | Deng Alor Kuol |

| Succeeded by | Ibrahim Ghandour |

| State Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 2005–2010 | |

| State Minister of Justice | |

| In office 2001–2005 | |

| Member of the National Assembly of Sudan | |

| In office 2000–2005 | |

| Constituency | South Shandi, River Nile State |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Ali Ahmed Karti 11 March 1953 or 27 October 1953 Hajar Alasal, Anglo-Egyptian Sudan |

| Political party | National Congress Party |

| Alma mater | University of Khartoum |

| Occupation | Politician, lawyer, businessman |

He previously served as State Minister of Foreign Affairs (2005–2010) and Justice (2001–2005) and was member of the National Assembly of Sudan from 2000 to 2005.

Early life and career

editKarti was born on 11 March or 27 October 1953 in Hajar Alasal, River Nile State.[1][2] He studied law at the University of Khartoum and obtained his degree in 1979.[3] Between 1979 and 1998 he worked as a consultant and lawyer.[2] At one point Karti attended training camps in Libya.[4] He was an erstwhile loyal supporter of Hassan al-Turabi.[5] In 1998 however he was a signatory of a memorandum against al-Turabi together with Ghazi Salah al-Din al-Atabani.[4]

During the 1990s he was one of the founders of Popular Defence Forces (PDF)[6] and from 1998 to 2000 he was its general coordinator (munassiq). He also served as its commander.[2][3][7][8] He oversaw the group during the Second Sudanese Civil War.[9] In leaked information from the United States Department of State on WikiLeaks Karti was also credited with organizing the Janjaweed which were active in the Darfur genocide.[9] On 12 January 2001, PDF forces attacked facilities of the International Committee of the Red Cross in Chelkou, Southern Sudan.[10]

Political career

editIn the late 1990s Karti became one of the founding members of the National Congress Party.[2]

During the 2000 Sudanese general election Karti was elected a member of the National Assembly of Sudan for South Shandi, River Nile State.[2] He held this office until 2005. From 2001 until 2005 he was State Minister at the Ministry of Justice.[2] In this period he flew to Darfur to buy the support of Arab tribal leaders with money supplied by Salah Gosh.[11] Subsequently he was State Minister at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs from 2005 until 2010.[2] In this period he was granted a visa to the United States to meet with Jendayi Frazer, the Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs.[10] He however did not show up to the meeting.[12] During the 2010 Sudanese general election he was once more elected for South Shandi, but became Minister of Foreign Affairs.[2] He succeeded Deng Alor Kuol.[3]

In May 2011 he and vice president Ali Osman Taha declined to meet with a United Nations Security Council delegation that investigated the crisis in Abyei.[13] In 2011 Karti met with Chinese diplomat Liu Guijin, who urged Sudan and South Sudan to work out their differences to keep oil transported between the two countries. In 2012 this was followed by visits from Chinese president Hu Jintao and vice president Xi Jinping.[14] During his term in office Karti requested the United States to remove Sudan from its list of State Sponsors of Terrorism.[9] He also tried to foster closer relations with African countries, opened an embassy in Rwanda and planned to open several others in different countries.[15] He also stated he want to mediate between Ethiopia and Egypt regarding the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, not wanting to take sides.[16][17]

In 2015 Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir formed a new government, and Karti was succeeded on 7 June by Ibrahim Ghandour.[18][19]

Post 2019 Sudanese coup d'état

editAfter the events of the 2019 Sudanese coup d'état, on 17 March 2020, the Sudanese prosecutor's office ordered his arrest for his role in the 1989 coup d'état which brought Omar al-Bashir to power. It said in a statement that his assets would be frozen.[20]

After the death of al-Zubeir Mohamed al-Hassan, Kharti became secretary general of the Sudanese Islamic Movement in June 2021. He was elected in a secret meeting by its Shura council.[21][22] Karti is alleged to have supported the 2021 Sudanese coup d'état in October.[8]

International sanctions

editIn September 2023, the United States imposed sanctions on Karti, accusing him of undermining the transition to a civil administration in Sudan since 2019. It also accused him undermining peace efforts between the Sudanese Armed Forces and the Rapid Support Forces in the War in Sudan.[21][23] Both the disbanded National Congress Party and the Sudanese Islamic Movement challenged the sanctions, and claimed pride could be derived from them.[8]

On June 24, 2024, the EU Council imposed personal sanctions on Karti for his continuous efforts to obstruct peace process between the SAF and the RSF as well as derailing Sudan's transition to civilian-led democracy.[24]

Business career

editKarti is a prominent Sudanese businessman, and bought the Friendship Hotel in Khartoum for $85 million at one point.[3] As of July 2023 he was seen as one of the richest people in Sudan.[5]

Personal life

editKarti is Muslim.[9] He is married and has one or more children.[2]

References

edit- ^ "Sudan Designations". Office of Foreign Assets Control. Archived from the original on 26 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "H.E. Mr. Ali Ahmed Karti Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of the Sudan - Curriculum Vitae" (PDF). Elcano Royal Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 November 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Ali Karti". www.sudantribune.com. Archived from the original on 13 October 2017.

- ^ a b Berridge, W.J. (2017). Hasan al-Turabi: Islamist Politics and Democracy in Sudan. Cambridge University Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-316-85186-9. Retrieved 3 February 2024.

- ^ a b Galindo, Antoine; Passilly, Augustine (10 July 2023). "Fugitive NCP veteran Ali Karti ready to pounce from the shadows". African Intelligence. Archived from the original on 25 September 2023.

- ^ Also mentioned as Public Defence Forces

- ^ Berridge, W.J. (2017). Hasan al-Turabi: Islamist Politics and Democracy in Sudan. Cambridge University Press. p. 298. ISBN 978-1-316-85186-9. Retrieved 3 February 2024.

- ^ a b c "Islamist leaders urge al-Burhan to continue fighting, pledge support". Sudan Tribune. 29 September 2023. Retrieved 3 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d Dias, Elizabeth (12 February 2015). "Sudan's Foreign Minister Denies War Crimes As UN Moves Toward New Sanctions". TIME. Archived from the original on 18 December 2023.

- ^ a b Grzyb, A.F. (2009). The World and Darfur: International Response to Crimes Against Humanity in Western Sudan. Arts Insights Series. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 260. ISBN 978-0-7735-7853-1. Retrieved 3 February 2024.

- ^ Flint, J.; de Waal, A. (2008). Darfur: A New History of a Long War. African Arguments. Zed Books. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-84813-639-7. Retrieved 3 February 2024.

- ^ Kessler, Glenn (13 May 2006). "Sudanese official is a no-show in Washington". Sudan Tribune. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ Dagne, T. (2012). The Republic of South Sudan: Opportunities and Challenges for Africa's Newest Country. DIANE Publishing Company. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-4379-8861-1. Retrieved 3 February 2024.

- ^ Li, H.Y. (2021). China's New World Order: Changes in the Non-Intervention Policy. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. p. 195. ISBN 978-1-78643-733-4. Retrieved 3 February 2024.

- ^ Copnall, J. (2014). A Poisonous Thorn in Our Hearts: Sudan and South Sudan's Bitter and Incomplete Divorce. Hurst. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-84904-493-6. Retrieved 3 February 2024.

- ^ Fahmy, N. (2020). Egypt's Diplomacy in War, Peace and Transition. Springer International Publishing. p. 142. ISBN 978-3-030-26388-1. Retrieved 3 February 2024.

- ^ Samaan, M.M. (2018). The Nile Development Game: Tug-of-War or Benefits for All?. Springer International Publishing. p. 200. ISBN 978-3-030-02665-3. Retrieved 3 February 2024.

- ^ "Sudan: President Omar al-Bashir forms a new government". BBC News. 7 June 2015. Archived from the original on 21 December 2023.

- ^ "The paths of return: Sudan's former regime and Islamist allies". Ayin network. 9 April 2023. Archived from the original on 15 December 2023.

- ^ "Sudan orders arrest of former foreign minister over 1989 coup". www.reuters.com. 17 March 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ a b "US sanctions former Sudan foreign minister Ali Karti". The East African. 29 September 2023. Archived from the original on 2 February 2024.

- ^ "Inside secret meetings of Sudanese Islamists". Sudan Tribune. 10 August 2022. Archived from the original on 10 November 2022.

- ^ "Afrique Guerre au Soudan: les États-Unis sanctionnent un ex-ministre et deux sociétés". www.rfi.fr. 29 September 2023. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- ^ "COUNCIL IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2024/1783 of 24 June 2024 implementing Regulation (EU) 2023/2147 concerning restrictive measures in view of activities undermining the stability and political transition of Sudan". Official Journal of the European Union.