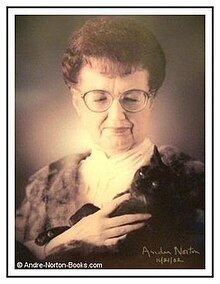

Andre Alice Norton (born Alice Mary Norton, February 17, 1912 – March 17, 2005) was an American writer of science fiction and fantasy, who also wrote works of historical and contemporary fiction. She wrote primarily under the pen name Andre Norton, but also under Andrew North and Allen Weston. She was the first woman to be Gandalf Grand Master of Fantasy,[2] to be SFWA Grand Master,[3] and to be inducted by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame.[4][5][6]

Andre Norton | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Alice Mary Norton February 17, 1912[1] Cleveland, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | March 17, 2005 (aged 93) Murfreesboro, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Pen name | Andre Norton Andrew North Allen Weston |

| Occupation | Writer, librarian |

| Period | 1934–2005 |

| Genre | Science fiction, fantasy, romance novels, adventure fiction |

| Notable awards | SFWA Grand Master, Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame |

Biography and career

editBiography

editAlice Mary Norton was born in Cleveland, Ohio in 1912.[7] Her parents were Adalbert Freely Norton, who owned a rug company, and Bertha Stemm Norton. Alice began writing at Collinwood High School in Cleveland, under the tutelage of Sylvia Cochrane. She was the editor of a literary page in the school's paper, The Collinwood Spotlight, for which she wrote short stories. During this time, she wrote her first book, Ralestone Luck, which was eventually published as her second novel in 1938.[8]

After graduating from high school in 1930, Norton planned to become a teacher, and began studying at Flora Stone Mather College of Western Reserve University. However, in 1932 she had to leave because of the Depression and began working for the Cleveland Library System,[8] where she remained for 18 years, latterly in the children's section of the Nottingham Branch Library in Cleveland. In a 1996 interview she recalled defending acquisition of The Hobbit by J. R. R. Tolkien for the library.[9] In 1934, she legally changed her name to Andre Alice Norton, a pen name she had adopted for her first book, published later that year, to increase her marketability, since boys were the main audience for fantasy.[8]

During 1940–1941, she worked as a special librarian in the cataloging department of the Library of Congress.[10] She was involved in a project related to alien citizenship which was abruptly terminated upon the American entry into World War II. In 1941 she bought a bookstore called Mystery House in Mount Rainier, Maryland, the eastern neighbor of Washington, D.C. The business failed, and she returned to the Cleveland Public Library until 1950, when she retired due to ill health.[11] She then began working as a reader for publisher-editor Martin Greenberg[a] at Gnome Press, a small press in New York City that focused on science fiction. She remained until 1958, when, with 21 novels published,[12][13] she became a full-time professional writer.

As Norton's health became uncertain, she moved to Winter Park, Florida in November 1966, where she remained until 1997.[14] She moved to Murfreesboro, Tennessee in 1997 and was under hospice care from February 21, 2005. She died at home on March 17, 2005, of congestive heart failure.

Literary career

editIn 1934, her first book, The Prince Commands, being sundry adventures of Michael Karl, sometime crown prince & pretender to the throne of Morvania, with illustrations by Kate Seredy, was published by D. Appleton–Century Company (cataloged by the U.S. Library of Congress as by "André Norton").[15][16] She went on to write several historical novels for the juvenile (now called "young adult") market.

Norton's first published science fiction was a short story, "The People of the Crater", which appeared under the name "Andrew North" as pages 4–18 of the inaugural 1947 number of Fantasy Book, a magazine from Fantasy Publishing Company, Inc.[17] Her first fantasy novel, Huon of the Horn, published by Harcourt Brace under her own name in 1951, adapted the 13th-century story of Huon, Duke of Bordeaux.[18] Her first science fiction novel, Star Man's Son, 2250 A.D., appeared from Harcourt in 1952.[19] She became a prolific novelist in the 1950s, with many of her books published for the juvenile market, at least in their original hardcover editions.

As of 1958, when she became a full-time professional writer, Kirkus had reviewed 16 of her novels,[b] and awarded four of them starred reviews.[13] Her four starred reviews to 1957 had been awarded for three historical adventure novels—Follow the Drum (1942), Scarface (1948), Yankee Privateer (1955)—and one cold war adventure, At Swords' Points (1954). She received four starred reviews subsequently, latest in 1966, including three for science fiction.[13]

Norton was twice nominated for the Hugo Award, in 1964 for the novel Witch World and in 1967 for the novelette "Wizard's World". She was nominated three times for the World Fantasy Award for lifetime achievement, winning the award in 1998. Norton won a number of other genre awards and regularly had works appear in the Locus annual "best of year" polls.[4]

She was a founding member of the Swordsmen and Sorcerers' Guild of America (SAGA), a loose-knit group of heroic fantasy authors founded in the 1960s, led by Lin Carter, with entry by fantasy credentials alone. Norton was the only woman among the original eight members. Some works by SAGA members were published in Lin Carter's Flashing Swords! anthologies.

In 1976, Gary Gygax invited Norton to play Dungeons & Dragons in his Greyhawk world. Norton subsequently wrote Quag Keep, which involved a group of characters who travel from the real world to Greyhawk. It was the first novel to be set, at least partially, in the Greyhawk setting and, according to Alternative Worlds, the first to be based on D&D.[20] Quag Keep was excerpted in Issue 12 of The Dragon (February 1978) just prior to the book's release.[21] She and Jean Rabe were collaborating on the sequel to Quag Keep when Norton died. Return to Quag Keep was completed by Rabe and published by Tor Books in January 2006.[17]

Her final complete novel, Three Hands for Scorpio, was published on April 1, 2005. Besides Return to Quag Keep, Tor has published two more novels with Norton and Rabe credited as co-authors, Dragon Mage (November 2006) and Taste of Magic (January 2008).[17]

-

Norton's novelette "The People of the Crater", published under her "Andrew North" pseudonym, was the cover story in the debut issue of Fantasy Book in 1947.

-

"The Gifts of Asti", also published under the "North" byline, took the cover of the third issue of Fantasy Book in 1948.

-

Cover of Voodoo Planet by Andrew North, artist Ed Valigursky; half of Ace Double #D-345 (1959)

Series

editNorton wrote more than a dozen speculative fiction series, but her longest, and longest-running project was "Witch World", which began with the novel Witch World in 1963. The first six novels were Ace Books paperback originals published from 1963 to 1968.[17] From the 1970s most of the books in the series were first published in hardcover editions.[17] From the 1980s some were written by Norton and a co-author, and others were anthologies of short fiction for which she was editor. (Witch World became a shared universe.)[c] There were dozens of books in all.[19]

The five novels of The Cycle of Oak, Yew, Ash, and Rowan, To the King a Daughter, Knight or Knave, A Crown Disowned, Dragon Blade, and The Knight of the Red Beard, were written with Sasha Miller.[22] The fifth and last novel was dedicated "To my late collaborator, Andre Norton, whose vision inspired the NordornLand cycle."[23] ("NordornLand cycle" is another name for this cycle.)

Legacy

editOften called the Grande Dame of Science Fiction and Fantasy by biographers such as J. M. Cornwell,[24] and organizations such as Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America,[25] Publishers Weekly,[26] and Time, Andre Norton wrote novels for more than 70 years. She had a profound influence on the entire genre, having more than 300 published titles read by at least four generations of science fiction and fantasy readers and writers. Notable authors who cite her influence include Greg Bear, Lois McMaster Bujold, C. J. Cherryh, Cecilia Dart-Thornton,[27] Tanya Huff,[28] Mercedes Lackey, Charles de Lint, Joan D. Vinge, David Weber, K. D. Wentworth, and Catherine Asaro.

On February 20, 2005, the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, which had honored Norton with its Grand Master Award in 1984, announced the creation of the Andre Norton Award, to be given each year for an outstanding work of fantasy or science fiction for the young adult literature market, beginning with 2005 publications. While the Norton Award is not a Nebula Award, it is voted on by SFWA members on the Nebula ballot and shares some procedures with the Nebula Awards.[29][30][31] Nominally for a young adult book, actually the eligible class is middle grade and young adult novels. This added a category for genre fiction to be recognized and supported for young readers.[32] Unlike Nebulas, there is a jury whose function is to expand the ballot beyond the six books with most nominations by members.

Norton received the Inkpot Award in 1989.[33]

High Hallack Library

editThe High Hallack Library was a facility that Norton was instrumental in organizing and opening. Designed as a research facility for genre writers, and scholars of "popular" literature (the genres of science fiction, fantasy, mystery, western, romance, gothic, and horror), it was located near Norton's home in Murfreesboro, Tennessee.[34]

The facility, named after one of the continents in Norton's Witch World series, was home to more than 10,000 texts, videos, and various other media. Attached to the facility were three guest rooms, allowing authors and scholars the chance to stay on-site to facilitate their research goals.[34]

The facility was opened on February 28, 1999, and operated until March 2004. Most of the collection was sold during the closing days of the facility. The declining health of Andre Norton was one of the leading causes of its closing.[34]

See also

editExplanatory notes

edit- ^ Martin Greenberg is no relation of Martin H. Greenberg (1941–2011) with whom Norton co-edited the Catfantastic series of five anthologies (DAW Books, 1989 to 1999).

- ^ Kirkus reviewed only hardcover first editions; at the time, Norton had only recently published her first paperback original, The Crossroads of Time (Ace Double, 1956).

- ^ Regarding The Duke's Ballad "by Andre Norton and Lyn McConchie", published in 2005, McConchie states "Witch World setting, marketed as by Andre Norton and Lyn McConchie, although all writing and revision done by Lyn using Andre's background." And she says much the same for all four of their Witch World novels (1995 to 2005).

"Lyn's Books". Lyn McConchie. Last updated 2012-09-17. Retrieved 2013-05-02.

Cited references

edit- ^ Andre M Norton, "United States Social Security Death Index". "United States Social Security Death Index", index, FamilySearch, March 17, 2005. Retrieved February 12, 2013. Citing U.S. Social Security Administration, Death Master File, database (Alexandria, Virginia: National Technical Information Service, ongoing).

- ^ Lehmann-Haupt, Christopher (March 18, 2005). "Andre Norton Dies at 93; a Master of Science Fiction". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- ^ "SFWA Grand Master Award Listings 1984". SFWA Grand Master Award Listings 1984. Archived from the original on January 10, 2003.

- ^ a b "Norton, Andre". Locus Index to SF Awards: Index of Literary Nominees. Locus Publications. Retrieved December 22, 2011.

- ^ "Damon Knight Memorial Grand Master". Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (SFWA). Archived from the original on July 1, 2011. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- ^ "Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame". Archived from the original on May 21, 2013.. Mid American Science Fiction and Fantasy Conventions, Inc. Retrieved March 27, 2013. This was the official website of the hall of fame to 2004.

- ^ Bankston, John. Andre Norton. New York: Chelsea House, 2010, p. 16.

- ^ a b c McLellan, Dennis (March 19, 2005). "Andre Norton, 93; A Prolific Science Fiction, Fantasy Author". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 25, 2022.

- ^ Coker III, John (January 29, 1996). "TO Classic: Days of Wonder – A Conversation with Andre Norton". Tangent Online. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ Bankston, John. Andre Norton. New York: Chelsea House, 2010, p. 50.

- ^ Steve Holland (July 6, 2013). "Obituary: Andre Norton | Books". The Guardian. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- ^ Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, "Andre Norton Dies at 93; a Master of Science Fiction", The New York Times, March 18, 2005. Retrieved October 26, 2009.

- ^ a b c "Kirkus Book Reviews". Kirkus. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ Maciej Zaleski-Ejgierd (February 17, 1912). "ANDRE NORTON ORG: Biography of Andre Norton". Andre-norton.org. Archived from the original on February 23, 2013. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- ^ "Norton, Andre". Archived from the original on October 18, 2015. Library of Congress Authorities. Library of Congress. Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- ^ The prince commands, being sundry adventures of Michael Karl, sometime ... LCCN 34003730. LCC record. Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Andre Norton at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database (ISFDB). Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- ^ "Bibliography: Huon of the Horn". ISFDB. Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- ^ a b "Andre Norton (1912–2005)", Locus, April 2005, pp. 5, 65.

- ^ Norton, Andre; Jean Rabe (2006). Return to Quag Keep. MacMillan. pp. Introduction. ISBN 0-7653-1298-0.

- ^ Norton, Andre (February 1978). "Quag's Keep (excerpts)". The Dragon (12). Lake Geneva WI: TSR: 22–30.

- ^ Andre Norton and Sasha Miller (2008), The Knight of the Red Beard, 2009 reprint, New York: Tor, p. [2].

- ^ Andre Norton and Sasha Miller (2008), The Knight of the Red Beard, 2009 reprint, New York: Tor, p. [7].

- ^ "An Interview with Andre Norton". Theroseandthornezine.com. Retrieved December 22, 2011.

- ^ "SFWA Biography". Archived from the original on October 9, 2009.

- ^ Andre Norton (2002). Fiction Book Review: Warlock. Author Baen Books. ISBN 978-0-671-31849-9. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "Interview with Cecilia Dart-Thornton". Future Fiction. August 2001. Archived from the original on January 6, 2013.

Other authors who have influenced and inspired me (in no particular order), include Nicholas Stuart Gray, George McDonald, Andre Norton ...

- ^ Switzer, David M; Schellenberg, James (October 1998). "Wizards, Vampires & a Cat: From the Imagination of Tanya Huff". Challenging Destiny (4). Crystalline Sphere Publishing.

I'd have to say the two general influences are Andre Norton for an incredibly varied body of work that can be read and enjoyed by both adults and twelve year olds ...

- ^ "2012 Nebula Awards Nominees Announced" (finalists). SFWA. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- ^

"Norton Award Blog Tour". SFWA. Retrieved 2013-04-27.

The Blog Tour preface (linked) incorporates a pertinent excerpt from the Nebula Awards rules. - ^ "About the Nebula Awards". Locus Index to SF Awards: About the Awards. Locus Publications. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- ^ Paulson, Kristin Leigh (2011). Overcoming the Stigma of Science Fiction and Fantasy in the Classroom: An Overview of the Andre Norton Award (MA thesis). University of Florida. OCLC 814394295.

- ^ "Inkpot Award". Comic-Con International: San Diego. December 6, 2012. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- ^ a b c "High Hallack Genre Writers' Research and Reference Library". Andre-Norton.org. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013., Retrieved May 31, 2013.

General sources

edit- Bankston, John. Andre Norton. New York: Chelsea House, 2010. ISBN 9781604136821

- Schlobin, Roger C. Andre Norton, a Primary and Secondary Bibliography. Boston: G.K. Hall, 1980. ISBN 081618044X

- Wolf, Virginia L. Andre Norton: Feminist Pied Piper in SF. Children's Literature Association Quarterly. Volume 10, Number 2, Summer 1985 pp. 66–70.

- Yoke, Carl B. Roger Zelazny and Andre Norton, Proponents of Individualism. Columbus: State Library of Ohio, 1979. OCLC 5902028

- Yoke, Carl B. "Slaying The Dragon Within: Andre Norton's Female Heroes", Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts, Vol. 4, No. 3 (15) (1991), pp. 79–93.

External links

editDigital collections

- Works by Andre Norton in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Andre Norton at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Andre Norton at the Internet Archive

- Works by Andre Norton at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

Institutional collections

- Andre Norton correspondences in the digital archives of Cleveland Public Library. The library also includes several images of the doll house she donated to the library, still on display in the Youth Services Department. One letter in the collection is from Houghton Mifflin Company concerning Andre Norton's application for a Literary Fellowship award.

- Andre (Alice Mary) Norton Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University

Other information

- Andre-Norton.com, "The Estate Authorized Andre Norton Website" w/ complete Bibliography and much more.

- "Andre Norton biography". Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame.

- Andre Norton at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Andre Norton at the Internet Book List

- Andre Norton at IMDb

- "Andre Norton :: Pen & Paper RPG Database". Archived from the original on January 19, 2005. Retrieved October 17, 2018.