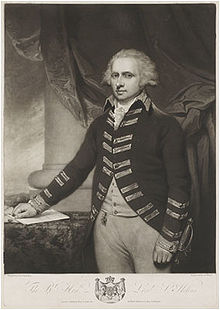

Alleyne FitzHerbert, 1st Baron St Helens, PC (1 March 1753 – 19 February 1839)[2] was a British diplomat. He was Minister Plenipotentiary to Russia from 1783 to 1788, appointed Chief Secretary for Ireland and a member of the Privy Council (Great Britain & Ireland) in 1787, serving in the former position until 1789. He was Minister plenipotentiary to Spain from 1790 to 1794.[2]

The Lord St Helens | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chief Secretary for Ireland | |

| In office 1787–1789 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas Orde-Powlett |

| Succeeded by | Robert Hobart |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1 March 1753 Derby |

| Died | 19 February 1839 (aged 85)[1] Grafton Street, London |

| Parent(s) | William and Mary Fitzherbert[1] |

| Education | St John's College, Cambridge |

| Occupation | diplomat |

He was a friend of explorer George Vancouver, who named Mount St. Helens in what is now the U.S. state of Washington after him.[3]

Life

editAlleyne was fifth and youngest son of William Fitzherbert of Tissington in Derbyshire, who married Mary, eldest daughter of Littleton Poyntz Meynell of Bradley, near Ashbourne.[1] His father, who was Member for the Borough of Derby and a Commissioner of the Board of Trade, committed suicide on 2 January 1772 due to pecuniary trouble. He was numbered among the friends of Dr. Johnson, who bore witness to his felicity of manner and his general popularity, but depreciated the extent of his learning. Of his mother the same authority is reported to have said that she had 'the best understanding he ever met with in any human being.' Alleyne, who inherited his baptismal name from his maternal grandmother, Judith, daughter of Thomas Alleyne of Barbados, was born in 1753. FitzHerbert was educated at Derby School (1763–1766), Eton College (1766–70) and St John's College, Cambridge (1770–1774).[1][2] His elder brother, also William inherited the family seat and became a baronet.

Cambridge

editIn July 1770 he matriculated as pensioner at St. John's College, Cambridge, his private tutor being the Rev. William Arnald, and in the following October Thomas Gray wrote to Mason that the little Fitzherbert is come as pensioner to St. John's, and seems to have all his wits about him.

Gray, attended by several of his friends, paid a visit to the young undergraduate in his college rooms, and as the poet rarely went outside his own college, his presence attracted great attention, and the details of the interview were afterwards communicated to Samuel Rogers, and printed by Mitford. Fitzherbert took his degree of B. A. in 1774, being second of the senior optimes in the mathematical tripos, and was also the senior chancellor's medallist.[4] Soon afterwards he went on a tour through France and Italy.

Diplomat

editIn February 1777 he began a long course of foreign life with the appointment of minister at Brussels, and this necessitated his taking the degree of M.A. in that year by proxy. He remained at Brussels until August 1782, when he was despatched to Paris by Lord Shelburne as plenipotentiary to negotiate a peace with the crowns of France and Spain, and with the States General of the United Provinces; and on 20 January 1783 the preliminaries of peace with the first two powers were duly signed. The peace with the American colonies, which was agreed to at about the same date, was not brought to a conclusion under Fitzherbert's charge, but he claimed to have taken a leading share in the previous negotiations which rendered it possible. This successful diplomacy led to his promotion in the summer of 1783 to the post of envoy extraordinary to the Empress Catherine of Russia, and he accompanied her in her tour round the Crimea in 1787.[1][5]

Spain

editWhen differences broke out between Great Britain and Spain respecting the right of British subjects to trade at Nootka Sound and to carry on the southern whale fishery, he was despatched to Madrid (May 1791) as ambassador extraordinary, and under his care all disputes were settled in the succeeding October, for which services he was raised to the Irish peerage with the title of Baron St. Helens.[1][6]

In the following year, Commander George Vancouver and the officers of HMS Discovery made the Europeans' first recorded sighting of Mount St. Helens on 19 May 1792, while surveying the northern Pacific Ocean coast. Vancouver named the mountain after the newly created Baron on 20 October 1792,[3] as it came into view when the Discovery passed into the mouth of the Columbia River.

A treaty of alliance between Great Britain and Spain was concluded by him in 1793, but as the climate of that country did not agree with his health he returned home early in 1794. Very shortly after his landing in England, St. Helens was appointed to the ambassadorship at the Hague (25 March 1794), where he remained until the French conquered the country, when the danger of his situation caused much anxiety to his friends.

A year or two later a great misfortune happened to him. On 16 July 1797 his house, containing everything he possessed, was burnt to the ground, and he himself narrowly escaped a premature death. He has lost, 'wrote Lord Minto, "every scrap of paper he ever had. Conceive how inconsolable that loss must be to one who has lived his life. All his books, many fine pictures, prints and drawings in great abundance, are all gone."[2]

Russia

editHis last foreign mission was to St. Petersburg in April 1801 to congratulate the Emperor Alexander I of Russia on his accession to the throne, and to arrange a treaty between England and Russia. The terms of the agreement were quickly settled, and on its completion he was promoted to the peerage of the United Kingdom as Baron St. Helen's, in the Isle of Wight and County of Southampton.[7] In the next September he attended the coronation of Alexander in Moscow, and arranged a convention with the Danish plenipotentiary, which was followed in March 1802 by a similar settlement with Sweden.[1]

Retirement

editThis completed his services abroad, and on 5 April 1803 he retired from diplomatic life with a pension of £2,300 a year. When Addington was forced to resign the premiership, St. Helens, who was much attached to George III, and was admitted to more intimate friendship with that king and his wife than any other of the courtiers, was created a lord of the bedchamber (May 1804), and the appointment is said to have been made against Pitt's wishes. He declared that he could not live out of London, and he therefore dwelt in Grafton Street all the year round. Although he repurchased Somersal Herbert Hall, an old family property, in 1806, he lent it for life to a cousin, the novelist Frances Jacson and her sister.[8] His consummate prudence and his quiet, polished manners are the theme of Nathaniel Wraxall's praise. Rogers and Jeremy Bentham were included in the list of his friends.[1]

To Rogers he presented in his last illness Pope's own copy of Garth's Dispensary, with Pope's manuscript annotations. Bentham had been presented to St. Helens by his elder brother, sometime member for Derbyshire, and many letters to and from him on subjects of political interest are in Bentham's works.[1] Two letters from him to Croker on Wraxall's anecdotes are in the 'Croker Papers (ii. 294–7), and a letter to him from the first Lord Malmesbury is printed in the latter's diaries. St. Helens died in Grafton Street, London, on 19 February 1839, and was buried in the Kensal Green Cemetery[9] on 26 February. As he was never married, the title became extinct, and his property passed to his nephew, Sir Henry Fitzherbert. From 1805 to 1837 he had been a trustee of the British Museum, and at the time of his death he was the senior member of the privy council.[1]

Personal life

editSt. Helens never married nor had children. However, he was known to have a very close relationship with Princess Elizabeth, third daughter of George III. Seventeen years older than Elizabeth, St. Helens was a frank, practical, and sharp-witted character known to dislike court life, qualities which Elizabeth shared. She referred to him as, "a dear and valuable saint," and said of him in a letter to her companion Lady Harcourt, "There is no man I love so well, and his tenderness to me has never varied, and that is a thing I never forget." Elizabeth later wrote that she pined for St. Helens, eager to see him, "at all times, hours, minutes, days, nights, etc."[10] Elizabeth later commissioned a portrait [11] of St. Helens from noted enamelist Henry Pierce Bone, evidence of her great attachment to him. St. Helens in turn kept an enamel miniature of Elizabeth, also painted by Bone.

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Dictionary of National Biography now in the public domain

- ^ a b c d Fitzherbert, Alleyne, Baron St Helens (1753–1839), diplomatist by Stephen M. Lee in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- ^ a b USGS. "Volcanoes and History: Cascade Range Volcano Names". Archived from the original on 28 October 2006. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

- ^ "Fitzherbert, Alleyne (FTST770A)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ Dyce's Recollections of Samuel Rogers pp. 104–5

- ^ "No. 13277". The London Gazette. 25 January 1791. p. 57.

- ^ "No. 15386". The London Gazette. 14 July 1801. p. 839.

- ^ ODNB entry for Frances Jacson: Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ Now resting in catacomb B Archived 4 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine The catacombs at Kensal Green Cemetery

- ^ Hadlow, Janice (2014). A Royal Experiment (1 ed.). New York: Henry Holt and Company, LLC. ISBN 978-0-8050-9656-9.[page needed]

- ^ https://ellisonfineart.com/alleyne-fitzherbert-17531839-1st-baron-st-helens-portrait{{Webarchive%7Curl=https://web.archive.org/web/20220517142220/https://ellisonfineart.com/alleyne-fitzherbert-17531839-1st-baron-st-helens%7Cdate=17 May 2022

External links

edit- Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1889). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 19. London: Smith, Elder & Co.