Alligator munensis is an extinct species of alligator from the Quaternary of Thailand. After the skull of A. munensis was discovered, it was tentatively assigned to the Chinese alligator before being recognized as a distinct species. Although the two are still considered to be close relatives, the pronounced anatomical differences suggest that the two species split from one another long prior to the Pleistocene, possibly during the uplifting of the Tibetan Plateau during the Miocene. It had a short and robust skull and may have had globular back teeth possibly corresponding to a greater amount of hard-shelled prey items. The nostrils of A. munensis were positioned much further towards the back of the skull than in other alligators, but the function of this is unknown.[1]

| Alligator munensis Temporal range: late Middle Pleistocene (possibly Holocene)

| |

|---|---|

| |

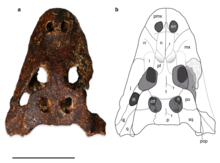

| Top view of Alligator munensis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Archosauromorpha |

| Clade: | Archosauriformes |

| Order: | Crocodilia |

| Family: | Alligatoridae |

| Genus: | Alligator |

| Species: | A. munensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Alligator munensis Darlim et al., 2023

| |

History and naming

editThe only currently known skull of Alligator munensis, specimen DMR-BSL2011-2, was discovered in 2005 in a layer of Quaternary alluvium in the village of Ban Si Liam, northeastern Thailand. The specimen was first discussed in a brief report by Claude et al. in 2011, who tentatively referred the material to the extant Chinese alligator (Alligator sinensis), although they already noted the distinct shape of this specimen. As the skull was in need of additional preparation, a detailed description was not possible until 2023, when Darlim and colleagues published their research on the skull. Using CT-scan data, Darlim and colleagues were able to compare the Thailand skull to material confidently assigned to Alligator sinensis, concluding that the material is different enough to warrant being placed in its own species. Furthermore, the team concludes based on other fossils from the same excavation that the locality that yielded these fossils dates to at least the middle Pleistocene, greatly narrowing down the timeframe from what was initially suggested by Claude et al. (who proposed it ranging from the Miocene to Pleistocene).

The species name of Alligator munensis references the Mun river, which is located near the site where the fossil of this species was found.[1]

Description

editThe skull of Alligator munensis is broadly triangular as in other alligators, but shows a remarkable level of compression that greatly shortens the overall length of the head. Furthermore, the rostrum was not especially flattened and still rather deep around the level of the nostrils, a condition otherwise known as altirostry. The region around the nose is raised thanks to an upturn of the nasal bones, which subsequently creates a marked ditch just behind the nares when observing the skull in profile view.[1]

Although the external nares are used to identify A. munensis as a member of the genus Alligator (the nares are separated from one another by the nasal bones), they are still unique compared to all other species of Alligator. They only cover about a third the length of the premaxilla, not two thirds like in other species. The bar that splits the nares is a lot broader in A. munensis, whereas it is thin in other species. Furthermore, while this internarial bar is typically formed mostly by the nasals, the premaxilla contribute heavily in the species from Thailand. The greater contribution of the premaxilla also extends to the back of the nares, where the bone wraps around and participates in the posterior border of these openings. The entire internarial bar is very high and partially separates the nasal cavity. Finally, the subcircular (rather than teardrop-shaped) nares are located much further back than in any other species of Alligator.[1]

The choana is also unique relative to all other species of the genus. It is almost circular with a sudden constriction towards the back, rather than elliptical, and it lacks the raised rim around the back of the opening.[1]

Several distinct ridges ornament the skull of Alligator munensis. One rostral ridge for example stretches across the maxilla and lacrimal bone, where it transitions to a further pair of ridges that span the prefrontal bones. This later pair of ridges, which is seen in all species except for A. mcgrewi, forms a structure referred to as spectacle. Additional ridges can be seen following the midlines of the nasals, the frontal bone and the parietal bone. Notably, the squamosals lack any distinct ridges or crests and are instead flat, whereas in today's Chinese alligator these bones are raised to form low horns.[1]

Alligator munensis had comparably reduced dentition. In addition to the typical five teeth in each premaxilla, it only possessed 12 teeth in either maxilla. Chinese alligators meanwhile possess 14 maxillary teeth. No teeth are known, but the 9th to 11th alveoli of the maxillae are clearly enlarged, which may correlate with the globular or blunt teeth. This could indicate a return to a more ancestral dentition, as today's generalist alligators evolved from more specialised ancestors.[1]

Phylogeny and evolution

editThe type description of A. munensis does not include a detailed phylogenetic tree, although the authors mention that such an analysis is in the works. Regardless of the absence of a phylogeny, Darlim et al. are confident in assigning this species to the genus Alligator based on a number of shared traits. Within Alligator, A. munensis shows many similarities to Alligator sinensis, suggesting the two were closely related. Nevertheless, the many derived features of this species indicate that the relationship between the two was not that of ancestor and descendant, but rather that they may have been divergent species.[1]

While it is not entirely clear when the two species diverged from one another, as the Alligator fossil record of Asia is only poorly studied, Darlim and colleagues have speculated on their origin. They propose that the ancestor of A. sinensis and A. munensis could have inhabited the lowlands that housed the proto Yangtze-Xi and Mekong-Chao Phraya river systems. When continued continental drift pushed up the eastern Tibetan Plateau during the Miocene, the two river systems would have been separated from one another, which consequently prevented the two resulting populations from interbreeding or dispersing into the others range. This would have caused both A. sinensis and A. munensis to evolve in isolation from one another, with the later being restricted to the proto-Chao Phraya river and later Mekong river system.[1]

Paleobiology

editBased on the deposits that Alligator munensis was found in, it may have inhabited similar environments as Chinese alligators, which includes lowlands and floodplains with a variety of waterbodies, including marshes, ponds and streams. A number of other animals were found in the same deposits as A. munensis, including softshell turtles and large mammals, specifically water buffalos and sambar deer.[1]

The enlarged posterior maxillary tooth sockets may suggest that the back teeth of A. munensis were either globular or blunt with flattened sides, which is seen in several short-snouted alligatoroids. This, coupled with the overall robust build of the skull and well developed attachment sites for jaw musculature, suggests that Alligator munensis had a strong bite suited to crush prey. Such a lifestyle has appeared in Crocodilia on numerous occasions, but also happens to be the ancestral state for alligatorines, meaning that today's generalist alligators came from more specialised ancestry. However, this does not necessarily indicate that A. munensis was more specialised as well, as the appearance of crushing dentition may connect to an even greater degree of opportunism, possibly in response to seasonally available hard-shelled prey. Darlim and colleagues point towards the omnivorous big-headed turtle, which will consume greater quantities of molluscs during certain periods of the year. Broad-snouted caimans on the other hand favor hard-shelled prey, yet lack the enlarged posterior teeth of other durophages. Chinese alligators also lack this particular adaptation, but their ecology is generally poorly understood.[1]

The function of the restracted nares of Alligator munensis is unknown, although similar conditions are seen in other animals. Similar adaptations for instance are seen in a number of secondarily marine animals like whales, ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, mesosaurs and the Jurassic metriorhynchoids, distant cousins of crocodilians. However, marine habits are dismissed not only due to the locality where A. munensis was found, but also due to the fact that no alligators are known to have possessed salt glands, rendering indefinite habitation of saltwater impossible. Among crown crocodilians, retracted nares are also seen in Purussaurus and, to a lesser degree, Siamese crocodiles as well as Crocodylus thorbjarnarsoni.[1]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Darlim, G.; Suraprasit, K.; Chaimanee, Y.; Tian, P.; Yamee, C.; Rugbumrung, M.; Kaweera, A.; Rabi, M. (2023). "An extinct deep-snouted Alligator species from the Quaternary of Thailand and comments on the evolution of crushing dentition in alligatorids". Sci Rep. 13 (10406). doi:10.1038/s41598-023-36559-6. PMC 10344928.