Alvan Tufts Fuller (February 27, 1878 – April 30, 1958) was an American businessman, politician, art collector, and philanthropist from Massachusetts. He opened one of the first automobile dealerships in Massachusetts, which in 1920 was recognized as "the world's most successful auto dealership",[1] and made him one of the state's wealthiest men. Politically a Progressive Republican, he was elected a member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives, was a delegate to the Republican National Convention in 1916, and served as a United States representative from 1917 to 1921.

Alvan T. Fuller | |

|---|---|

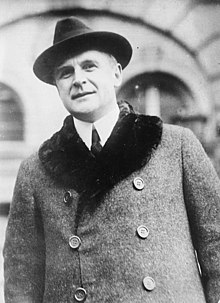

Fuller circa 1920 | |

| 50th Governor of Massachusetts | |

| In office January 8, 1925 – January 3, 1929 | |

| Lieutenant | Frank G. Allen |

| Preceded by | Channing H. Cox |

| Succeeded by | Frank G. Allen |

| 48th Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts | |

| In office January 6, 1921 – January 8, 1925 | |

| Governor | Channing H. Cox |

| Preceded by | Channing H. Cox |

| Succeeded by | Frank G. Allen |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Massachusetts's 9th district | |

| In office March 4, 1917 – January 5, 1921 | |

| Preceded by | Ernest W. Roberts |

| Succeeded by | Charles L. Underhill |

| Member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives | |

| In office 1914–1917 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Alvan Tufts Fuller February 27, 1878 Charlestown, Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | April 30, 1958 (aged 80) Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican Progressive |

| Spouse | Viola Theresa Davenport |

| Children | 4, including Peter D. Fuller |

| Profession | Motor Car Dealer |

From 1925 to 1929 Fuller was the 50th governor of Massachusetts, continuing the fiscally conservative and socially moderate policies of his predecessors. In 1927 he was enveloped in the international controversy surrounding the trial and execution of Sacco and Vanzetti, Italian immigrant anarchists convicted of robbery and murder. Fuller's handling of the affair, in which both domestic and international sources sought clemency for the two, effectively ended his political career.

Fuller was an avid collector of art, some of which has since been donated to museums in eastern New England, including the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. He founded the Fuller Foundation, a charity that supports a variety of causes in eastern Massachusetts and the seacoast region of New Hampshire. Fuller Gardens, founded by him in North Hampton, New Hampshire, are now open to the public.[1]

Early years

editAlvan Tufts Fuller was born in the Charlestown neighborhood of Boston on February 27, 1878, to working-class parents,[2] Alvan Bond and Flora Arabella (Tufts) Fuller.[3][4] His family moved to Malden, Massachusetts, when he was still a child. He first worked in a rubber factory, repairing bicycles on the side. To promote his bicycle business he raced, winning local events.[2] He also engaged in a practice, shared by other bicycle shops in the area, of holding an open house on the Washington's Birthday holiday.[5] Through an entirely paternal line Alvan T. Fuller was descended from English Puritan settler Captain Matthew Fuller.[6] He was also distantly related to Benjamin Franklin.[7]

Automotive business empire

editEnamored by the new automobile, Fuller sold his racing trophies to finance a trip to Europe in 1899, where he learned more about the automobile industry.[2] He acquired two cars (French De Dion-Bouton voiturettes),[3] and had them shipped to Boston; they were the first motor vehicles brought in through that port.[2] In 1903 he was awarded the Boston franchise for selling Packards,[8] and later also acquired the local Cadillac franchise.[2]

Fuller was enormously successful in the automobile business, extending his sales reach as far west as Worcester and south to Providence, Rhode Island. He opened his first dealership on Commonwealth Avenue in the Allston neighborhood of Boston, then a largely undeveloped area known by sheer coincidence as Packard's Corner, after the owner of a nearby livery yard.[2] He was, however, soon followed by other auto dealers, creating the Boston area's first auto row.[9] Fuller was a significant factor in the success of Packard sales on the east coast,[8] and was in 1920 dubbed the world's most successful car dealer.[1] In 1927 he began construction on a new building at 808 Commonwealth Avenue. Designed by the noted industrial architect Albert Kahn, it became the flagship showroom for his Cadillac dealership. It is now owned by Boston University, and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[10]

As a car dealer, Fuller continued the practice of holding Washington's Birthday open houses, but the scale of events he staged was significantly more elaborate, and he is generally credited with popularizing the idea of the President's Day car sale that is now common in the United States.[5]

Political career

editCongress

editFuller became interested in politics around 1912, supporting Theodore Roosevelt in his Bull Moose candidacy for the presidency. He refused the Progressive Party nomination for Governor of Massachusetts in 1912, but won election to the Massachusetts House of Representatives in 1914 under its banner.[3] Joining the Republican Party in 1916, he served as a delegate to its convention in 1916. The same year, he ran for the United States House of Representatives as an independent, winning a 16-vote victory over longtime incumbent Republican Ernest W. Roberts.[11] He served two terms, in the Sixty-fifth and Sixty-sixth Congresses, from March 4, 1917, to January 5, 1921,[12] winning election to the second term by a wider margin as a Republican.[11]

Fuller was an outspoken proponent of reform within Congress, and as a matter of principle never cashed paychecks he received for his public service, or used the Congressional franking privilege.[11] He criticized the inefficient means by which legislation made its way through Congress, calling it "the most expensive barnacle that ever attached itself to the ship of state."[13] Criticisms such as these prompted President Woodrow Wilson to introduce a new and more centralized budgeting system in 1919.[13] Reforms Fuller proposed included a number of steps designed to increase transparency and reduce opportunities for political influence within the operations of Congress.[14]

In 1920, Fuller ran for Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts, and won two terms, serving as the 48th lieutenant governor from 1921 to 1925 alongside Governor Channing Cox. His principal opposition in both elections was in the Republican primary, where he was pitted against the Speaker of the Massachusetts House of Representatives, Joseph E. Warner.[11] The Democrats were then relatively disorganized and lacking effective leadership, and were unable to counter the basic Republican message of "economy and sound administration" that had characterized recent elections.[15]

Governor

editFuller was elected 50th Governor in 1924[16] after Cox decided not run for reelection.[17] The 1924 election was against the colorful Mayor of Boston James Michael Curley. Fuller's campaign rhetoric focused on the excesses of what it called "Curleyism", which it likened to a "graft-ridden spending spree".[18] Curley attempted to tie Fuller to the Ku Klux Klan, but his charges were exposed as meritless – Fuller's wife was Roman Catholic (a group the Klan disliked), and Fuller was known to have contributed to Catholic charities.[11] Fuller was reelected by a substantial majority in 1926 over William A. Gaston, in a campaign dominated by Democratic calls for reform of Prohibition.[19] As he had while in Congress, Fuller refused compensation for his services.[20]

Fuller was viewed as a law and order pro-death penalty governor and a fiscal conservative. He was, like his predecessors, a social moderate, enacting modest reforms in areas such as automobile insurance.[21]

Fuller's tenure as governor coincided with the Sacco and Vanzetti case, a series of trials for murder and robbery followed by legal appeals that culminated in domestic and international calls for the governor to either grant a new trial, or to commute the death sentences, of the two Italian immigrants active in anarchist political circles. He appointed a three-member panel, consisting of Harvard President Abbott Lawrence Lowell, MIT President Dr. Samuel W. Stratton, and retired Probate Judge Robert Grant to conduct a complete review of the case and determine if the trials were fair.[22] The committee reported that no new trial was called for and based on that assessment Governor Fuller refused to delay their executions or grant clemency. On May 10, 1927, while Fuller was considering requests for clemency, a package bomb addressed to him was intercepted in the Boston post office.[23] A few months after the executions, he endorsed proposals to reform the state's judicial procedures to require a more thorough review of capital cases.[24] The episode led to Fuller being characterized in the international press as provincial, and the controversy surrounding the cases and criticism of his handling of it (which was widely seen to exacerbate rather than diminish political tensions) effectively ended his hopes for higher office.[25] New York Times reporter Louis Stark repeated a widely held belief that Fuller's decision to deny clemency was motivated by a desire to succeed Calvin Coolidge in the presidency, but there is no substantive evidence to corroborate this idea, beyond the coincident timing of Coolidge's announced decision not run in 1928 and Fuller's decision.[26][27] In 1930, Fuller stated in an interview that he was more concerned about the political activities of the two men and their supporters, which he saw as a threat to order and security of the United States.[28] When Fuller was offered a print edition of The Letters of Sacco and Vanzetti in 1929 at the inauguration of his successor, he deliberately threw it to the ground.[29]

In 1928, Fuller was an early supporter of Herbert Hoover's presidential campaign, after considering his own run for the presidency,[30] and was briefly considered as a candidate for vice president. He was dropped from consideration because, as Republican Senator William Borah put it, "The Republican Party cannot afford to spend the summer debating the Sacco-Vanzetti case."[31] His handling of the case was seen to reduce support for the ticket among immigrant communities.[25] He was dropped from consideration by the Hoover administration for consideration as United States Ambassador to France after the French government indicated it could not guarantee his safety due to the Sacco-Vanzetti affair.[25] (When the controversy was at its height in 1927, the Fullers had traveled to France, and the French government had secretly provided heightened security around their movements.)[32] Fuller considered running for Senate in 1930 and Governor in 1934, but dropped out of the primaries in those races. In 1933, he was appointed by the Public Works Administration (PWA) to a board overseeing the distribution of PWA funds in Massachusetts. He was again considered as a vice presidential nominee in 1932, but ran well back in the convention balloting.[25]

Later years

editAfter leaving office, Fuller returned to his automotive business, serving as chairman of the board of Cadillac-Oldsmobile Co. of Boston. In 1949 he dropped the Packard dealership, and focused exclusively on the Cadillac and Oldsmobile brands.[25]

Fuller was a philanthropist and art collector, serving as a trustee of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA). Painters represented in his collection included Renoir,[33] Rembrandt, Turner, Gainsborough, Sargent, Monet, van Dyck, Romney, Boccaccino,[34] Boucher and Reynolds. Paintings that he and his successors donated to the National Gallery of Art in Washington and the MFA include: Monet's "The Water Lily Pond," Renoir's "Boating Couple," and van Dyck's "Princess Mary, Daughter of Charles I."[35] His philanthropy was wide-ranging and included art, hospitals, education, religion, municipalities and social services.[25] He established The Fuller Foundation, Inc., during his lifetime; still in operation, it supports many charitable agencies in the Greater Boston area and the Seacoast Region of New Hampshire.[1]

Fuller died in Boston on April 30, 1958.[12] He was interred in East Cemetery (also known as the Little River Cemetery) in North Hampton, New Hampshire, where he had a summer home.[36] The summer property included a large garden that the Fullers developed, with landscape design guidance by Arthur Shurtleff and the Olmsted Brothers. It is now open to the public seasonally.[37]

Family and legacy

editFuller married Viola Theresa Davenport of Somerville in Paris in 1910, with whom he had four children, two boys and two girls. She had a brief career as an opera singer, performing in Paris and then debuting in Boston in 1910. She died in 1959.[38]

Peter D. Fuller, his youngest son, was an avid supporter of civil rights and continued the family auto business. He was the owner of Dancer's Image, the horse that won the 1968 Kentucky Derby,[39] but was disqualified because a drug banned in Kentucky was found via a post-race urine test. Fuller subsequently lost a four-year legal battle to retain the Kentucky Derby title and prize money.[40] Fuller also owned Mom's Command, the American Champion Three-Year-Old Filly in 1985 that was ridden in most races by Fuller's daughter Abigail.

Fuller's automobile dealership, established with license #1, continues to be operated within the family. Now dealing in rentals and used vehicles, it has locations in Watertown and Waltham, Massachusetts.[41]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d "About the founder". Fuller Foundation. 26 May 2015. Retrieved 2016-03-30.

- ^ a b c d e f Clarke, p. 48

- ^ a b c Herman, p. 208

- ^ "The Minute Man". 1927.

- ^ a b DeMarco, Peter (February 19, 2012). "On Presidents' Day, hail to the chief salesman". Boston Globe. Retrieved 2016-03-30.

- ^ Genealogy of Some Descendants of Captain Matthew Fuller, John Fuller of Newton, John Fuller of Lynn, John Fuller of Ipswich, Robert Fuller of Dorchester and Dedham: To which is Added Supplements to Volume I: Genealogy of Some Descendants of Edward Fuller of the Mayflower, and Volume II: Some Descendants of Dr. Samuel Fuller of the Mayflower. compiler. 1914.

- ^ "Family relationship of Benjamin Franklin and Alvan T. Fuller via Josiah Franklin". famouskin.com. Retrieved 2024-10-24.

- ^ a b Einstein, p. 32

- ^ Clarke, pp. 48–49

- ^ "MACRIS inventory record for Peter Fuller Building". Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Retrieved 2017-02-28.

- ^ a b c d e Gentile, p. 540

- ^ a b "Milestones, May 12, 1958". Time. Archived from the original on April 22, 2009. Retrieved 2010-06-24.

- ^ a b Guide to Congress, p. 58

- ^ Haines, p. 12

- ^ Huthmacher, p. 49

- ^ Huthmacher, p. 111

- ^ "Uncertainty in Massachusetts". New York Times. May 6, 1924.

- ^ Huthmacher, p. 106

- ^ Huthmacher, p. 145

- ^ "Fuller Explains Refusal of Salary". New York Times. September 20, 1926. Retrieved July 24, 2010.

- ^ Gentile, pp. 540-541

- ^ "Appoints Advisers for Sacco Inquiry". New York Times. June 2, 1927. Retrieved 2010-01-06.

- ^ Watson, pp. 303-4

- ^ "Fuller Urges Change in Criminal Appeals". New York Times. January 5, 1928. Retrieved 2010-06-22.

- ^ a b c d e f Gentile, p. 541

- ^ Neville, p. 109

- ^ Temkin, pp. 84-86

- ^ Temkin, p. 84

- ^ Temkin, p. 288

- ^ Bullard, F. Lauriston (January 29, 1928). "Bay Staters Cast Fuller's Hat in Ring". New York Times. Retrieved 2010-06-24.

- ^ Jouhgin and Morgan, p. 314

- ^ Neville, p. 76

- ^ "Alvan Fuller Renoir's Boating Couple". Museum of Fine Arts. Retrieved 2017-02-28.

- ^ "Alvan Fuller donates Boccaccino's Shepherd Boy Playing Bagpipes". Museum of Fine Arts. Retrieved 2017-02-28.

- ^ "Fuller donates van Dyck". Museum of Fine Arts. Retrieved 2017-02-28.

- ^ "Gov. Fuller Won't Run". New York Times. June 26, 1928. Retrieved 2010-06-24.

- ^ "Garden History". Fuller Gardens. 24 May 2013. Retrieved 2017-02-28.

- ^ "Mrs. Alvan Fuller Dies". New York Times. August 5, 1959. Retrieved 2010-06-24.

- ^ Tower, Whitney (May 13, 1968). "And The Last Was First". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on April 10, 2013. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- ^ Martin, Douglas (May 19, 2012). "Peter D. Fuller Dies at 89; Had to Return Derby Purse". New York Times. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- ^ "About Peter Fuller". Peter Fuller Rentals & Pre-Owned. Retrieved 2016-03-29.

Sources

edit- Guide to Congress, Seventh Edition, Volume 1. Thousand Oaks, CA: Congressional Quarterly Press. 2013. ISBN 9781452235325. OCLC 815668911.

- Clarke, Theodore (2010). Brookline, Allston-Brighton, and the Renewal of Boston. Charleston, SC: History Press. ISBN 9781609491857. OCLC 681534964.

- Einstein, Arthur Jr. (2010). "Ask the Man Who Owns One": An Illustrated History of Packard Advertising. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 9780786456611. OCLC 667274241.

- Gentile, Richard H (1999). "Fuller, Alvan Tufts". Dictionary of American National Biography. Vol. 8. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 540–541. ISBN 9780195206357. OCLC 39182280.

- Haines, Lynne (May 1919). "Making Congress Function: An Interview With Alvan T. Fuller". The Searchlight.

- Herman, Jennifer (2008). Massachusetts Encyclopedia. Hamburg, MI: State History Publications. ISBN 9781878592651. OCLC 198759722.

- Huthmacher, J. Joseph (1959). Massachusetts People and Politics, 1919-1933. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press. OCLC 460668046.

- Joughlin, Louis; Morgan, Edmund M (1978) [1948]. The Legacy of Sacco and Vanzetti. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400868650. OCLC 908042195.

- Neville, John (2004). Twentieth-century Cause Cèlébre: Sacco, Vanzetti, and the Press, 1920-1927. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 9780275977832. OCLC 237853843.

- Temkin, Moshik (2009). The Sacco-Vanzetti Affair: America on Trial. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300156171. OCLC 586143213.

- Watson, Bruce (2007). Sacco and Vanzetti: The Men, the Murders, and the Judgment of Mankind. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 9780670063536.