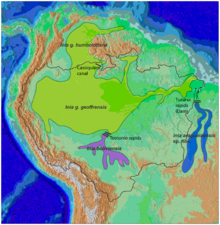

The Amazon river dolphin (Inia geoffrensis), also known as the boto, bufeo or pink river dolphin, is a species of toothed whale endemic to South America and is classified in the family Iniidae. Three subspecies are currently recognized: I. g. geoffrensis (Amazon river dolphin), I. g. boliviensis (Bolivian river dolphin) and I. g. humboldtiana (Orinoco river dolphin). The position of the Araguaian river dolphin (I. araguaiaensis) within the clade is still unclear.[3][4] The three subspecies are distributed in the Amazon basin, the upper Madeira River in Bolivia, and the Orinoco basin, respectively.

| Amazon river dolphin | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

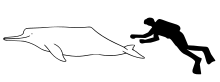

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Iniidae |

| Genus: | Inia |

| Species: | I. geoffrensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Inia geoffrensis (Blainville, 1817)

| |

| |

| Amazon river dolphin range | |

The Amazon river dolphin is the largest species of river dolphin, with many adult males reaching 185 kilograms (408 lb) in weight, and 2.5 metres (8.2 ft) in length. Adults acquire a pink color, more prominent, in males, giving it its nickname "pink river dolphin". Sexual dimorphism is very evident, with males measuring 16% longer and weighing 55% more than females. Like other toothed whales, they have a melon, an organ that is used for bio sonar. The dorsal fin, although short in height, is regarded as long, and the pectoral fins are also large. The fin size, unfused vertebrae, and its relative size allow for improved manoeuvrability when navigating flooded forests and capturing prey.

They have one of the widest ranging diets among toothed whales, and feed on up to 53 different species of fish, such as croakers, catfish, tetras and piranhas. They also consume other animals such as river turtles, aquatic frogs, and freshwater crabs.[5]

In 2018, this species was ranked by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as endangered, with a declining population.[1] Threats include incidental catch in fishing lines, direct hunting for use as fish bait or predator control, damming, and pollution; as with many species, habitat loss and continued human development is becoming a greater threat.[1]

It is the only species of river dolphin kept in captivity, mainly in Venezuela and Europe. It is difficult to train and a high mortality rate is seen among captive individuals.

Taxonomy

editThe species Inia geoffrensis was described by Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville in 1817. Originally, the Amazon river dolphin belonged to the superfamily Platanistoidea, which constituted all river dolphins, making them a paraphyletic group.[6] Today, however, the Amazon river dolphin has been reclassified into the superfamily Inioidea.[7] There is no consensus on when and how their ancestral species penetrated the Amazon basin; they may have done so during the Miocene from the Pacific Ocean, before the formation of the Andes, or from the Atlantic Ocean.[8][9]

There is ongoing debate about the classification of species and subspecies. The IUCN and Committee on Taxonomy of the Society for Marine Mammalogy recognize two subspecies: I. g. geoffrensis (Amazon river dolphin) and I. g. boliviensis (Bolivian river dolphin).[1][10] A third proposed subspecies, I. g. humboldtiana (Orinoco river dolphin),[7] was first described in 1977.[10][11] Molecular analysis suggests that the Orinoco dolphins are derived from the Amazon population and are not genetically distinct. Comparative morphological research also indicates that I. g. humboldtiana is not distinguishable from I. g. geoffrensis.[12] However, Cañizales (2020) found that I. g. humboldtiana skulls were morphologically distinct and recommended that it be elevated to species status.[13]

In 1994, it was proposed that I. g. boliviensis was a different species based on skull morphology.[14] In 2002, following the analysis of mitochondrial DNA specimens from the Orinoco basin, the Putumayo River (tributary of the Amazon) and the Tijamuchy and Ipurupuru rivers, geneticists proposed that genus Inia be divided into at least two evolutionary lineages: one restricted to the river basins of Bolivia and the other widely distributed in the Orinoco and Amazon.[15][16] A recent study, with more comprehensive sampling of the Madeira system, including above and below the Teotonio Rapids (which were thought to obstruct gene flow), found that the Inia above the rapids did not possess unique mtDNA.[17] As such the species level distinction once held is not supported by current results. Therefore, the Bolivian river dolphin is currently recognized as a subspecies. In addition, a 2014 study identifies a third species in the Araguaia-Tocantins basin,[18] but this designation is not recognized by any international organization and the Committee on Taxonomy of the Society for Marine Mammalogy suggests this analysis is not persuasive.[10]

Subspecies

editInia geoffrensis geoffrensis[7] inhabits most of the Amazon River, including rivers Tocantins, Araguaia, low Xingu and Tapajos, the Madeira to the rapids of Porto Velho, and rivers Purus, Yurua, Ica, Caqueta, Branco, and the Rio Negro through the channel of Casiquiare to San Fernando de Atabapo in the Orinoco river, including its tributary: the Guaviare.

Inia geoffrensis boliviensis[7] has populations in the upper reaches of the Madeira River, upstream of the rapids of Teotonio, in Bolivia. It is confined to the Mamore River and its main tributary, the Iténez.[19]

Inia geoffrensis humboldtiana[7] are located in the Orinoco River basin, including the Apure and Meta rivers. This subspecies is restricted, at least during the dry season, to the waterfalls of Rio Negro rapids in the Orinoco between Puerto Samariapo and Puerto Ayacucho, and the Casiquiare canal. This subspecies is not recognized by the Committee on Taxonomy of the Society for Marine Mammalogy,[10] or the IUCN.[1]

Description

editThe Amazon river dolphin is the largest river dolphin. Adult males reach a maximum length and weight of 2.55 metres (8.4 ft) (average 2.32 metres (7.6 ft)) and 185 kilograms (408 lb) (average 154 kilograms (340 lb)), while females reach a length and weight of 2.15 metres (7.1 ft) (mean 2 metres (6.6 ft)) and 150 kilograms (330 lb) (average 100 kilograms (220 lb)). It has very evident sexual dimorphism, with males measuring and weighing between 16% and 55% more than females, making it unique among river dolphins, where females are generally larger than males.[20]

The texture of the body is robust and strong but flexible. Unlike in oceanic dolphins, the cervical vertebrae are not fused, allowing the head to turn 90 degrees.[21] The flukes are broad and triangular, and the dorsal fin, which is keel-shaped, is short in height but very long, extending from the middle of the body to the caudal region. The pectoral fins are large and paddle-shaped. The length of its fins allows the animal to perform a circular movement, allowing for exceptional maneuverability to swim through the flooded forest but decreasing its speed.[22]

The body color varies with age. Newborns and the young have a dark grey tint, which in adolescence transforms into light grey, and in adults turns pink as a result of repeated abrasion of the skin surface. Males tend to be pinker than females due to more frequent trauma from intra-species aggression. The color of adults varies between solid and mottled pink and in some adults the dorsal surface is darker. It is believed that the difference in color depends on the temperature, water transparency, and geographical location. There was one albino on record, kept in an aquarium in Germany.[citation needed]

The skull of the species is slightly asymmetrical compared to the other toothed whales. It has a long, thin snout, with 25 to 28 pairs of long and slender teeth to each side of both jaws. Dentition is heterodont, meaning that the teeth differ in shape and length, with differing functions for both grabbing and crushing prey. Anterior teeth are conical and later have ridges on the inside of the crown. Despite small eyes, the species seems to have good eyesight in and out of the water. It has a melon on the head, the shape of which can be modified by muscular control when used for biosonar. Breathing takes place every 30 to 110 seconds.[22]

Longevity

editLife expectancy of the Amazon river dolphin in the wild is unknown, but in captivity, the longevity of healthy individuals has been recorded at between 10 and 30 years. However, a 1986 study of the average longevity of this species in captivity in the United States is only 33 months.[23] An individual named Baby at the Duisburg Zoo, Germany, lived at least 46 years, spending 45 years, 9 months at the zoo.[24]

Biology and ecology

editThe Amazon river dolphin are commonly seen singly or in twos, but may also occur in pods that rarely contain more than eight individuals.[25] Pods as large as 37 individuals have been seen in the Amazon, but the average is three. In the Orinoco, the largest observed groups number 30, but the average is just above five.[25] During prey time, as many as 35 pink dolphins work together to obtain their prey.[26] Typically, social bonds occur between mother and child, but may also been seen in heterogeneous groups or bachelor groups. The largest congregations are seen in areas with abundant food, and at the mouths of rivers. There is significant segregation during the rainy season, with males occupying the river channels, while females and their offspring are located in flooded areas. However, in the dry season, there is no such separation.[21][27] Due to the high level of prey fish, larger group-sizes are seen in large sections that are directly influenced by whitewater (such as main rivers and lakes, especially during low water season) than in smaller sections influenced by blackwater (such as channels and smaller tributaries).[25] In their freshwater habitat they are apex predators and gatherings depend more on food sources and habitat availability than in oceanic dolphins where protection from larger predators is necessary.[25]

Captive studies have shown that the Amazon river dolphin is less shy than the bottlenose dolphin, but also less sociable. It is very curious and has a remarkable lack of fear of foreign objects. However, dolphins in captivity may not show the same behavior that they do in their natural environment, where they have been reported to hold the oars of fishermen, rub against boats, pluck underwater plants, and play with sticks, logs, clay, turtles, snakes, and fish.[7]

They are slow swimmers; they commonly travel at speeds of 1.5 to 3.2 kilometres per hour (0.93 to 1.99 mph) but have been recorded to swim at speeds up to 14 to 22 kilometres per hour (8.7 to 13.7 mph). When they surface, the tips of the snout, melon and dorsal fins appear simultaneously, the tail rarely showing before diving. They can also shake their fins, and pull their tail fin and head above the water to observe the environment. They occasionally jump out of the water, sometimes as high as a meter (3.14 ft). They are harder to train than most other species of dolphin.[7]

Courtship

editAdult males have been observed carrying objects in their mouths such as branches or other floating vegetation, or balls of hardened clay. The males appear to carry these objects as a socio-sexual display which is part of their mating system. The behavior is "triggered by an unusually large number of adult males and/or adult females in a group, or perhaps it attracts such into the group. A plausible explanation of the results is that object-carrying is aimed at females and is stimulated by the number of females in the group, while aggression is aimed at other adult males and is stimulated by object-carrying in the group."[28] Before determining that the species had an evident sexual dimorphism, it was postulated that the river dolphins were monogamous. Later, it was shown that males were larger than females and are documented wielding an aggressive sexual behavior in the wild and in captivity. Males often have a significant degree of damage in the dorsal, caudal, and pectoral fins, as well as the blowhole, due to bites and abrasions. They also commonly have numerous secondary teeth-raking scars. This suggests fierce competition for access to females, with a polygynous mating system, though polyandry and promiscuity cannot be excluded.[29]

In captivity, courtship and mating foreplay have been documented. The male takes the initiative by nibbling the fins of the female, but reacts aggressively if the female is not receptive. A high frequency of copulations in a couple was observed; they used three different positions: contacting the womb at right angles, lying head to head, or head to tail.[9]

Reproduction

editBreeding is seasonal, and births occur between May and June. The period of birthing coincides with the flood season, and this may provide an advantage because the females and their offspring remain in flooded areas longer than males. As the water level begins to decrease, the density of food sources in flooded areas increases due to loss of space, providing enough energy for infants to meet the high demands required for growth. Gestation is estimated to be around eleven months and captive births take 4 to 5 hours. At birth, calves are 80 centimetres (31 in) long and in captivity have registered a growth of 0.21 metres (0.69 ft) per year. Lactation takes about a year. The interval between births is estimated between 15 and 36 months, and the young dolphins are thought to become independent within two to three years.[9]

The relatively long duration of breastfeeding and parenting suggests a high level of parental care. Most couples observed in their natural environment consist of a female and her calf. This suggests that long periods of parental care contribute to learning and development of the young.[9]

Diet

editThe diet of the Amazon river dolphin is the most diverse of the toothed whales. It consists of at least 53 different species of fish, grouped in 19 families. The prey size is between 5 and 80 centimetres (2.0 and 31.5 in), with an average of 20 centimetres (7.9 in). The most frequently consumed fish belong to the families Sciaenidae (croakers), Cichlidae (cichlids), Characidae (characins and tetras), and Serrasalmidae (pacus, piranhas and silver dollars).[30] The dolphin's dentition allows it to access shells of river turtles (such as Podocnemis sextuberculata) and freshwater crabs (such as Poppiana argentiniana).[5][7][30] The diet is more diverse during the wet season, when fish are spread in flooded areas outside riverbeds, thus becoming more difficult to catch. The diet becomes more selective during the dry season when prey density is greater.[22]

Usually, these dolphins are active and feeding throughout the day and night. However, they are predominantly crepuscular. They consume about 5.5% of their body weight per day. They sometimes take advantage of the disturbances made by boats to catch disoriented prey. Sometimes, they associate with the distantly related tucuxi (Sotalia fluviatilis), and giant otters (Pteronura brasiliensis) to hunt in a coordinated manner, by gathering and attacking fish stocks at the same time. Apparently, there is little competition for food between these species, as each prefers different prey. It has also been observed that captive dolphins share food.[5][7]

Echolocation

editAmazonian rivers are often very murky, and the Amazon river dolphin is therefore likely to depend much more on its sense of echolocation than vision when navigating and finding prey. However, echolocation in shallow waters and flooded forests may result in many echoes to keep track of. For each click produced a multitude of echoes are likely to return to the echolocating animal almost on top of each other which makes object discrimination difficult. This may be why the Amazon river dolphin produces less powerful clicks compared to other similar sized toothed whales.[31] By sending out clicks of lower amplitude only nearby objects will cast back detectable echoes, and hence fewer echoes need to be sorted out, but the cost is a reduced biosonar range. Toothed whales generally do not produce a new echolocation click until all relevant echoes from the previous click have been received,[32] so if detectable echoes are only reflected back from nearby objects, the echoes will quickly return, and the Amazon river dolphin is then able to click at a high rate.[31] This in turn allow these animals to have a high acoustic update rate on their surroundings which may aid prey tracking when echolocating in shallow rivers and flooded forests with plenty of hiding places for the prey. While preying in murky water, they emit series of clicking noises, 30 to 80 per second, which they use by listening to the bouncing sonar which bounces off their prey.[26]

Communication

editLike other dolphins, river dolphins use whistling tones to communicate. The issuance of these sounds is related to the time they return to the surface before diving, suggesting a link to food. Acoustic analysis revealed that the vocalisations are different in structure from the typical whistles of other species of dolphins.[33]

Distribution and population

editAmazon river dolphins are the most widespread river dolphins. They are present in six countries in South America: Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela, in an area covering about 7 million square kilometres (2.7 million square miles). The boundaries are set by waterfalls, such as the Xingu and Tapajós rivers in Brazil, as well as very shallow water. A series of rapids and waterfalls in the Madeira River have isolated one population, recognized as the subspecies I. g. boliviensis, in the southern part of the Amazon basin in Bolivia.[7]

They are also distributed in the basin of the Orinoco River, except the Caroni River and the upper Caura River in Venezuela. The only connection between the Orinoco and the Amazon is through the Casiquiare canal. The distribution of dolphins in the rivers and surrounding areas depends on the time of year; in the dry season they are located in the river beds, but in the rainy season, when the rivers overflow, they disperse to the flooded areas, both the forests and the plains.[7]

Studies to estimate the population are difficult to analyze due to the difference in the methodology used. In a study conducted in the stretch of the Amazon called Solimões River, with a length of 1,200 kilometres (750 mi) between the cities of Manaus and Tabatinga, a total of 332 individuals was sighted ± 55 per inspection. Density was estimated at 0.08–0.33 animals per square kilometer in the main channels, and 0.49 to 0.93 animals per square kilometer in the branches. In another study, on a stretch of 120 kilometres (75 mi) at the confluence of Colombia, Brazil and Peru, 345 individuals with a density of 4.8 per square km in the tributaries around the islands. 2.7 and 2.0 were observed along the banks. Additionally, another study was conducted in the Amazon at the height of the mouth of the Caqueta River for six days. As a result of the studies conducted, it was found that the density is higher in the riverbanks, 3.7 per km, decreasing towards the center of the river. In studies conducted during the rainy season, the density observed in the flood plain was 18 animals per square km, while on the banks of rivers and lakes ranged from 1.8 to 5.8 individuals per square km. These observations suggest that the Amazon river dolphin is found in higher density than any other cetacean.[7]

Habitat and migration

editThe Amazon river dolphin is located in most of the area's aquatic habitats, including; river basins, major courses of rivers, canals, river tributaries, lakes, and at the ends of rapids and waterfalls. Cyclical changes in the water levels of rivers take place throughout the year. During the dry season, dolphins occupy the main river channels, and during the rainy season, they can move easily to smaller tributaries, to the forest, and to floodplains.[9]

Males and females appear to have selective habitat preferences, with the males returning to the main river channels when water levels are still high, while the females and their offspring remain in the flooded areas as long as possible; probably because it decreases the risk of aggression by males toward the young and predation by other species.[9]

In the Pacaya-Samiria National Reserve, Peru, photo-identification is used to recognize individuals based on pigmentation patterns, scars and abnormalities in the beak. 72 individuals were recognized, of which 25 were again observed between 1991 and 2000. The intervals between sightings ranged from one day to 7.5 years. The maximum range of motion was 220 kilometres (140 mi), with an average of 60.8 kilometres (37.8 mi). The longest distance in one day was 120 kilometres (75 mi), with an average of 14.5 kilometres (9.0 mi).[34] In a previous study conducted at the center of the Amazon River, a dolphin was observed that moved only a few dozen kilometers from the dry season and wet season. However, three of the reviewed 160 animals were observed over 100 kilometres (62 mi) from where they were first registered.[19] Research in 2011 concluded that photo-identification by skilled operatives using high-quality digital equipment could be a useful tool in monitoring population size, movements and social patterns.[35]

Interactions with humans

editIn captivity

editThe Amazon river dolphin has historically been kept in dolphinariums. Today, only one exists in captivity, at Zoologico de Quistochoca in Peru. Several hundred were captured between the 1950s and 1970s, and were distributed in dolphinariums throughout the US, Europe, and Japan. Around 100 went to US dolphinariums, and of that, only 20 survived; the last died at the Pittsburgh Zoo in 2002.[21]

Threats

editThe region of the Amazon in Brazil has an extension of 5,000,000 km2 (1,900,000 sq mi) containing diverse fundamental ecosystems.[36][37] One of these ecosystems is a floodplain, or a várzea forest, and is home to a large number of fish species which are an essential resource for human consumption.[38] The várzea is also a major source of income through excessive local commercialized fishing.[36][39][40] Várzea consists of muddy river waters containing a vast number and diversity of nutrient rich species.[28] The abundance of distinct fish species lures the Amazon River dolphin into the várzea areas of high water occurrences during the seasonal flooding.[41]

In addition to attracting predators such as the Amazon river dolphin, these high-water occurrences are an ideal location to draw in the local fisheries. Human fishing activities directly compete with the dolphins for the same fish species, the tambaqui (Colossoma macropomum) and the pirapitinga (Piaractus brachypomus), resulting in deliberate or unintentional catches of the Amazon river dolphin.[42][43][44][36][45][46][47][48] The local fishermen overfish and when the Amazon River dolphins remove the commercial catch from the nets and lines, it causes damages to the equipment and the capture, as well as generating ill will from the local fishermen.[44][46][47] The negative reactions of the local fishermen are also attributed to the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources prohibition on killing the Amazon river dolphin, yet not compensating the fishermen for the damage done to their equipment and catch.[48]

During the process of catching the commercialized fish, the Amazon river dolphins get caught in the nets and exhaust themselves until they die, or the local fishermen deliberately kill the entangled dolphins.[38] The carcasses are discarded, consumed, or used as bait to attract a scavenger catfish, the piracatinga (Calophysus macropterus).[38][49] The use of the Amazon river dolphin carcass as bait for the piracatinga dates back to 2000.[49] Increasing demand for the piracatinga has created a market for distribution of the Amazon river dolphin carcasses to be used as bait throughout these regions.[48]

Of the 15 dolphin carcasses found in the Japurá River in 2010–2011 surveys, 73% of the dolphins were killed for bait, disposed of, or abandoned in entangled gillnets.[38] The data do not fully represent the actual overall number of deaths of the Amazon river dolphins, whether accidental or intentional, because a variety of factors make it extremely complicated to record and medically examine all the carcasses.[38][43][46] Scavenger species feed upon the carcasses, and the complexity of the river currents make it nearly impossible to locate all of the dead animals.[38] More importantly, the local fishermen do not report these deaths out of fear that a legal course of action will be taken against them,[38] as the Amazon river dolphin and other cetaceans are protected under a Brazilian federal law prohibiting any takes, harassments, and kills of the species.[50]

The Amazon river is also threatened by the dumping of mercury into its waters from industrial mining, along with other harsh chemicals. Just like deforestation and burning, mercury in the water of the Amazon river is very dangerous for the fauna of the river. In 2019, F. Mosquera-Guerra at al, published a study that showed the presence of mercury in the Amazon river dolphins. They analyzed the dolphin's muscle tissue of different taxa of the Amazon basin and found high concentrations of mercury in the Tapajos River (Brazil) from an adult male of I. g. geoffrensis (pink dolphin).[51]

In September 2023, 154 Amazon river dolphins died in Brazil's Lake Tefé following record-high water temperatures of 40 °C (104 °F) and reduced water levels during a drought. While there are ongoing studies by the Mamirauá Institute for Sustainable Development to determine the cause of the deaths, the leading hypothesis is that the elevated temperature caused algae in the lake to release a toxin that attacks the central nervous system.[52][53]

Conservation

editIn 2008, the International Whaling Commission (IWC) expressed concern for captured botos for use as bait in the Central Amazon, which is an emerging problem that has spread on a large scale. The species is listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species Fauna and Flora (CITES), and Appendix II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals,[54] because it has an unfavorable conservation status or would benefit significantly from international co-operation organized by tailored agreements.

According to a previous assessment by the Scientific Committee of the International Whaling Commission in 2000, the population of botos appears great and there is little or no evidence of population decline in numbers and range. However, increased human intervention on their habitat is expected to, in the future, be the most likely cause of the decline of its range and population. A series of recommendations were issued to ensure proper follow-up to the species, among which is the implementation and publication of studies on the structure of populations, making a record of the distribution of the species, information about potential threats as the magnitude of fishing operations and location of pipelines.[55]

In September 2012, Bolivian President Evo Morales enacted a law to protect the dolphin and declared it a national treasure.[21][56]

In 2018, the species was listed on the Red list of endangered species.[1]

Increasing pollution and gradual destruction of the Amazon rainforest add to the vulnerability of the species. The biggest threats are deforestation and other human activities that contribute to disrupt and alter their environment.[7] Another source of concern is the difficulty in keeping these animals alive in captivity, due to intra-species aggression and low longevity. Captive breeding is not considered a conservation option for this species.[57]

The Global Declaration for River Dolphins seeks to reverse the decline of river dolphin populations throughout the world. As of early 2024, 11 of the 14 countries that have river dolphins have signed the declaration.[52]

In mythology

editIn traditional Amazon River folklore, at night, an Amazon river dolphin becomes a handsome young man who seduces girls, impregnates them, and then returns to the river in the morning to become a dolphin again. Similarly, the female becomes a beautiful, well-dressed, wealthy-looking young woman. [58] She goes to the house of a married man, places him under a spell to keep him quiet, and takes him to a thatched hut and visits him every year on the same night she seduced him. On the 7th night of visiting, she changes the man into a baby – female or male, and soon transfers it into his own wife's womb. The mythology is said to be the cycle of a baby. [citation needed] This dolphin shapeshifter is called an encantado. The myth has been suggested to have arisen partly because dolphin genitalia bear a resemblance to those of humans. Others believe the myth served (and still serves) as a way of hiding the incestuous relations which are quite common in some small, isolated communities along the river.[58] In the area, tales relate it is bad luck to kill a dolphin. Legend also states that if a person makes eye contact with an Amazon river dolphin, they will have lifelong nightmares. According to the pink Amazon river dolphin myth, it is said that this creature takes form of a human and seduces men and women to the Underworld of Encante. This underworld place is said to be 'Atlantis-like Paradise', yet no one has come back from it alive. Myths say that whoever kills the amazon dolphin will have bad luck, but it's worse for whoever eats it.[59] Local legends also state that the dolphin is the guardian of the Amazonian manatee, and that if one should wish to find a manatee, one must first make peace with the dolphin.

Associated with these legends is the use of various fetishes, such as dried eyeballs and genitalia.[58] These may or may not be accompanied by the intervention of a shaman. A recent study has shown, despite the claim of the seller and the belief of the buyers, none of these fetishes is derived from the boto. They are derived from Sotalia guianensis, are most likely harvested along the coast and the Amazon River delta, and then are traded up the Amazon River. In inland cities far from the coast, many, if not most, of the fetishes are derived from domestic animals such as sheep and pigs.[60]

Gallery

edit-

Amazon river dolphin skull (Inia geoffrensis)

-

Heart of the Amazon river dolphin

-

Amazon river dolphin (Inia geoffrensis)

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f da Silva, V.; Trujillo, F.; Martin, A.; Zerbini, A.N.; Crespo, E.; Aliaga-Rossel, E.; Reeves, R. (2018). "Inia geoffrensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T10831A50358152. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T10831A50358152.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ Hrbek, Tomas; Da Silva, Vera Maria Ferreira; Dutra, Nicole; Gravena, Waleska; Martin, Anthony R.; Farias, Izeni Pires (22 January 2014). Turvey, Samuel T. (ed.). "A New Species of River Dolphin from Brazil or: How Little Do We Know Our Biodiversity". PLOS One. 9 (1): e83623. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...983623H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0083623. PMC 3898917. PMID 24465386.

- ^ "List of Marine Mammal Species & Subspecies". Society for Marine Mammalogy. Archived from the original on 6 January 2015.

- ^ a b c American Cetacean Society Fact Sheet. "Boto (Amazon river dolphin)". American Cetacean Society. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- ^ The Paleobiology database. "Superfamily Platanistoidea". fossilworks. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Wilson, Don; Reeder, DeeAnn (2005). Mammal Species of the World. Vol. 2. JHU Press. p. 738. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ Hamilton, H.; S. Caballero; A. G. Collins & R. L. Brownell Jr. (2001). "Evolution of river dolphins". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 268 (1466): 549–556. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1385. PMC 1088639. PMID 11296868.

- ^ a b c d e f Bebej, Ryan (2006). "Inia geoffrensis (Amazon river dolphin)". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d "List of Marine Mammal Species and Subspecies - Society for Marine Mammalogy". www.marinemammalscience.org. 13 November 2016. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ Pilleri, George; Gihr, Margarethe (1977). "Observations on the Bolivian (Inia boliviensis D'orbigny, 1834) and the Amazonian Bufeo (Inia geoffrensis de Blainville, 1817) with Description of a New Subspecies (Inia geoffrensis humboldtiana)". Investigations on Cetacea. 8: 11–76.

- ^ Trujillo, F.; Crespo, E.; Van Damme, P.A.; Usma, J.S. (2010). The Action Plan for South American River Dolphins 2010 – 2020. Bogotá, D.C., Colombia: WWF, Fundación Omacha, WDS, WDCS, Solamac. pp. 22–25.

- ^ Cañizales, Israel (27 October 2020). "Morphology of the skull of Inia geoffrensis humboldtiana Pilleri & Gihr, 1977 (Cetacea: Iniidae): A morphometric and taxonomic analysis". Graellsia. 76 (1). doi:10.3989/graellsia.2020.v76.253. ISSN 0367-5041. S2CID 228995991.

- ^ Martínez-Agüero, M.; S. Flores-Ramírez & M. Ruiz-García (2006). "First report of major histocompatibility complex class II loci from the Amazon pink river dolphin (genus Inia)" (PDF). Genetics and Molecular Research. 5 (3): 421–431. PMID 17117356. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 27 May 2009.

- ^ Banguera-Hinestroza, E; Cardenas, H; Ruiz-García, M; Marmontel, M; Gaitan, E; Vazquez Garcia-Vallejo, F (2002). "Molecular identification of evolutionarily significant units in the Amazon River dolphin Inia sp. (Cetacea: Iniidae)". Journal of Heredity. 93 (5): 312–322. doi:10.1093/jhered/93.5.312. PMID 12547919.

- ^ Perrin, William; Würsig, Bernd; Thewissen, J.G.M. (2002). "Amazon River Dolphin". Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Elsevier Science. pp. 26–28. ISBN 978-0-12-373553-9.

- ^ Gravena, Waleska; Farias, Izeni P.; Silva, Maria N. F. da; Silva, Vera M. F. da; Hrbek, Tomas (1 June 2014). "Looking to the past and the future: were the Madeira River rapids a geographical barrier to the boto (Cetacea: Iniidae)?". Conservation Genetics. 15 (3): 619–629. doi:10.1007/s10592-014-0565-4. ISSN 1566-0621. S2CID 14569447.

- ^ Hrbek, Tomas; da Silva, Vera Maria Ferreira; Dutra, Nicole; Gravena, Waleska; Martin, Anthony R.; Farias, Izeni Pires (22 January 2014). "A New Species of River Dolphin from Brazil or: How Little Do We Know Our Biodiversity". PLOS ONE. 9 (1): e83623. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...983623H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0083623. PMC 3898917. PMID 24465386.

- ^ a b Da Silva, V.; Martin, AR. (2000). "The status of the Amazon River dolphin (Blainville, 1817): a review of available information". International Whaling Commission.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ Martin, A.; da Silva, V. (2006). "Sexual dimorphism and body scarring in the boto (Amazon River dolphin) Inia geoffrensis" (PDF). Marine Mammal Science. 22 (1): 25–33. Bibcode:2006MMamS..22...25M. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2006.00003.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d Klinowska, Margaret; Cooke, Justin (1991). Dolphins, Porpoises, and Whales of the World: the IUCN Red Data Book (PDF). pp. 52–59. ISBN 978-2-88032-936-5. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ^ a b c Robin C. Best; Vera M.F. da Silva (1993). "Inia geoffrensis" (PDF). Mammalian Species (426): 1–8. doi:10.2307/3504090. JSTOR 3504090. S2CID 253962191. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ^ Caldwell, Melba C.; Caldwell, David K.; Brill, Randall L. (1986). "Inia geoffrensis in Captivity in the United States" (PDF). IUCN Species Survival Commission: 35–41. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ "Zoo Duisburg trauert um einzigartigen Flussdelfin" (in German). 2020. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d Gomez-Salazar, C.; F. Trujillo; H. Whitehead (2011). "Ecological factors influencing group sizes of river dolphins (Inia geoffrensis and Sotalia fluviatilis)". Marine Mammal Science. 28 (2): E124–E142. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2011.00496.x.

- ^ a b Hansel, Eric (30 December 2013). "Pink River Dolphin". Wilderness Classroom. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- ^ Martin, A.; da Silva, V. (2004). "River dolphins and flooded forest: seasonal habitat use and sexual segregation of Botos (Inia geoffrensis) cetacean in an extreme environment". Journal of Zoology. 263 (3): 295–305. doi:10.1017/s095283690400528x.

- ^ a b Martin, A.R.; Da Silva, V.M.F.; Rothery, P. (2008). "Object carrying as social–sexual display in an aquatic mammal". Biology Letters. 4 (3): 243–245. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2008.0067. PMC 2610054. PMID 18364306.

- ^ Best, R.; da Silva, V. (1984). "Preliminary Analysis of Reproductive Parameters of the boutu, Inia geoffrensis, and the Tucuxi, tucuxi, in the Amazon River System". Report of the International Whaling Commission. 6 (Special Issue): 361–369.

- ^ a b "Inia geoffrensis (Amazon river dolphin)". Animal Diversity Web.

- ^ a b Ladegaard, Michael; Jensen, Frants Havmand; de Freitas, Mafalda; Vera M.F., da Silva; Madsen, Peter Teglberg (2015). "Amazon river dolphins (Inia geoffrensis) use a high-frequency short-range biosonar". Journal of Experimental Biology. 218 (Pt 19): 3091–3101. doi:10.1242/jeb.120501. hdl:1912/7584. PMID 26447198.

- ^ Au, Whitlow W.L. (1993). The Sonar of Dolphins. New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 115–118. ISBN 978-0-387-97835-2.

- ^ Podos, Jeffrey; Vera da Silva, MF; Marcos Rossi-Santos, R. (2002). "Vocalizations of Amazon River Dolphins: Insights into the Evolutionary Origins of delphinid Whistles". Ethology. 108 (7): 601–612. doi:10.1046/j.1439-0310.2002.00800.x.

- ^ McGuire, TL.; Henningsen, T. (2007). "Movement Patterns and Site Fidelity of River Dolphins (Inia geoffrensis and Sotalia fluviatilis) in the Peruvian Amazon as Determined by Photo-Identification". Aquatic Mammals. 33 (3): 359–367. doi:10.1578/AM.33.3.2007.359.

- ^ Gomez-Salazar, Catalina; Trujillo, Fernando; Whitehead, Hal (2011). "Photo-Identification - A Reliable and Noninvasive Tool for Studying Pink River Dolphins, Inia geoffrensis" (PDF). Aquatic Mammals. 37 (4): 472–485. doi:10.1578/am.37.4.2011.472.

- ^ a b c Silvano, R.A.M.; Ramires, M.; Zuanon, J. (2009). "Effects of fisheries management on fish communities in the floodplain lakes of a Brazilian Amazonian Reserve". Ecology of Freshwater Fish. 18 (1): 156–166. Bibcode:2009EcoFF..18..156S. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0633.2008.00333.x.

- ^ Barletta, M.; Jaureguizar, A.J.; Baigun, C.; Fontoura, N.F.; Agostinho, A.A.; Almeida-Val, V.M.F.; Val, A.L.; Torres, R.A.; Jimenes-Segura, L.F.; Giarrizzo, T.; Fabré, N.N.; Batista, V.S.; Lasso, C.; Taphorn, D.C.; Costa, M.F.; Chaves, P.T.; Vieria, J.P.; Corrêa, M.F.M. (2010). "Fish and aquatic habitat conservation in South America: A continental overview with an emphasis on Neotropical systems". Journal of Fish Biology. 76 (9): 2118–2176. Bibcode:2010JFBio..76.2118B. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2010.02684.x. PMID 20557657.

- ^ a b c d e f g Iriarte, V.; Marmontel, M. (2013). "River Dolphin (Inia geoffrensis, Sotalia fluviatilis) Mortality Events Attributed to Artisanal Fisheries in the Western Brazilian Amazon". Aquatic Mammals. 39 (2): 116–124. doi:10.1578/am.39.2.2013.116.

- ^ Isaac, V.J.; Ruffino, M.L. (2007). "Evaluation of fisheries in Middle Amazon". American Fisheries Society Symposium. 49: 587–596.

- ^ Neiland, A.E.; Benê, C. (2008). Tropical River Fisheries Valuation:Background papers to a global synthesis. Penang, Malaysia: The World Fish Center. p. 290.

- ^ Arraut, E.M.; M. Marmontel; J.E. Mantovani; E.M. Novo; D.W. Macdonald; R.E. Kenward (2009). "The lesser of two evils: seasonal migrations of Amazonian manatees in the Western Amazon". Journal of Zoology. 280 (3): 247–256. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2009.00655.x.

- ^ Reeves, R.R.; Smith, B.D.; Crespo, E.A.; Notarbartolo di Sciara, G. (2003). Dolphins, whales and porpoises: 2002–2010 conservation action plan for the world's cetaceans. Gland, Switzerland, and Cambridge, UK: International Union for Conservation of Nature/Species Survival Committee. p. 139.

- ^ a b Martin, A.R.; Da Silva, V.M.F.; Rothery, P. (2008). "Number, seasonal movements, and residency characteristics of river dolphins in an Amazonian floodplain lake system". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 82 (8): 1307–1315. doi:10.1139/z04-109.

- ^ a b Loch, C.; Marmontel, M.; Simões-Lopes, P.C. (2009). "Conflicts with fisheries and intentional killing of freshwater dolphins (Cetacea: Odontoceti) in the Western Brazilian Amazon". Biodiversity Conservation. 18 (14): 3979–3988. Bibcode:2009BiCon..18.3979L. doi:10.1007/s10531-009-9693-4. S2CID 20873255.

- ^ Beltrán-Pedreros, S.; Filgueiras-Henriques, L.A. (2010). Biology, evolution and conservation of river dolphins within South America and Asia. New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc. pp. 237–246.

- ^ a b c Crespo, E.A.; Alarcon, D.; Alonso, M.; Bazzalo, M.; Borobia, M.; Cremer, M.; Filla, G.F.; Lodi, L.; Magalhães, F.A.; Marigo, J.; Queiróz, H.L.; Reynolds, J.E. III; Schaeffer, Y.; Dorneles, P.R.; Lailson-Brito, J.; Wetzel, D.L. (2010b). "Report on the working group on major threats and conservation". The Latin American Journal of Aquatic Mammals. 8 (1–2): 47–56. doi:10.5597/lajam00153. hdl:11336/98669.

- ^ a b Iriarte, V.; Marmontel, M. (2011). "Report of an encounter with a human intentionally entagled Amazon River dolphin (Inia geoffrensis) calf and its release in Tefé River, Amazonas State, Brazil". Uakari. 7 (2): 47–56.

- ^ a b c Alves, L.C.P.S.; Andriolo, A.; Zappes, C.A. (2012). "Conflicts between river dolphins (Cetacea:Odontoceti) and fisheries in the Central Amazon: A path toward tragedy?". Zoologia. 29 (5): 420–429. doi:10.1590/s1984-46702012000500005.

- ^ a b Estupiñán, G.; Marmontel, M.; Queiroz, H.L.; Roberto e Souza, P.; Valsecchi, J.; da Silva Batista, G.; Barbosa Pereira, S. "A pesca da piracatinga (Calophysus macropterus') na Reserva de Desenvolvimiento Sustentável Mamirauá [The piracatinga fishery (Calophysus macropterus) at Mamirauá Sustainable Development Reserve]". Brazilian Ministry of Science and Technology. Archived from the original on 28 July 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ^ Lodi, L.; Barreto, A. (1998). "Legal actions taken in Brazil for the conservation of cetaceans". Journal of International Wildlife Law and Policy. I (3): 403–411. doi:10.1080/13880299809353910.

- ^ Mosquera-Guerra, F.; Trujillo, F.; Parks, D.; Oliveira-da-Costa, M.; Van Damme, P. A.; Echeverría, A.; Franco, N.; Carvajal-Castro, J. D.; Mantilla-Meluk, H.; Marmontel, M.; Armenteras-Pascual, D. (December 2019). "Mercury in Populations of River Dolphins of the Amazon and Orinoco Basins". EcoHealth. 16 (4): 743–758. doi:10.1007/s10393-019-01451-1. ISSN 1612-9202. PMID 31712931. S2CID 207942099.

- ^ a b Arellano, Astrid (15 January 2024). "11 countries sign global pact to protect endangered river dolphins". Mongabay Environmental News.

- ^ Ionova, Ana; Albeck-Ripka, Livia (4 October 2023). "A Lake Turned to a Hot 'Soup.' Then the River Dolphins Died". The New York Times.

- ^ Bonn, Alemania (2010). "Inia geoffrensis (de Blainville, 1817)" (PDF). Unep/CMS: 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ IWC Scientific Committee (2000). "Report of the Scientific Sub-Committee on Small Cetaceans". International Whaling Commission.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ "Bolivia enacts law to protect Amazon pink dolphins". BBC News. 18 September 2012.

- ^ Caldwell, M.; Caldwell, D.; Brill, R. (1989). "Inia geoffrensis in Captivity in the United States". IUCN Species Survival Commission. 3: 35–41.

- ^ a b c M. A. Cravalho (1999). "Shameless creatures: An ethnozoology of the Amazon river dolphin". Ethnology. 38 (1): 47–58. doi:10.2307/3774086. JSTOR 3774086.

- ^ Dunnell, Tony (1 February 2019). "Myths And Legends of the Amazon's Pink River Dolphin". South American Vacations. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ Gravena, W.; T. Hrbek; V.M.F. da Silva & I.P. Farias (2008). "Amazon river dolphin love fetishes: From folklore to molecular forensics". Marine Mammal Science. 24 (4): 969–978. Bibcode:2008MMamS..24..969G. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2008.00237.x.

External links

edit- Omacha Foundation—A non-government and non-profit organization created to study, research and protect river dolphins and other fauna and aquatic ecosystems in Colombia. Winner of the 2007 Whitley Awards (UK).

- River Dolphin Research Program—Research project devoted to the study of the ecology and conservation of river dolphins in the Amazon basin, based in the Federal University of Western Pará. The scope of this research project focuses on ecological studies, as well as the impact that human activities have on their survival.

- Convention on Migratory Species page on the Amazon Dolphin