Amadeo Pietro Giannini (Italian pronunciation: [amaˈdɛːo ˈpjɛːtro dʒanˈniːni]), also known as Amadeo Peter Giannini or A. P. Giannini (May 6, 1870 – June 3, 1949) was an American banker who founded the Bank of Italy, which eventually became Bank of America. Giannini is credited as the inventor of many modern banking practices. Most notably, Giannini was one of the first bankers to offer banking services to middle-class Americans, mainly Italian immigrants, rather than only the upper class. He also pioneered the holding company structure and established one of the first modern trans-national institutions.[1]

Amadeo Giannini | |

|---|---|

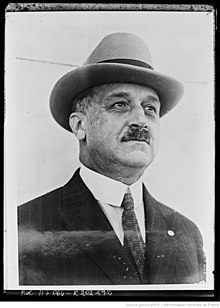

Amadeo Giannini (1927) | |

| Born | Amadeo Pietro Giannini May 6, 1870 San Jose, California, U.S. |

| Died | June 3, 1949 (aged 79) San Mateo, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Holy Cross Catholic Cemetery |

| Other names | A. P. Giannini |

| Spouse | Clorinda Cuneo |

| Children | 6, including Claire Giannini Hoffman |

| Parents |

|

Background

editAmadeo Pietro Giannini was born in San Jose, California, to Italian immigrant parents.[2][3] He was the first son of Luigi Giannini (1840–1877) and Virginia (née Demartini) Giannini (1854–1920). Luigi Giannini immigrated to the United States from Favale di Malvaro near Genoa, Liguria in the Kingdom of Sardinia (later part of Italy) to prospect in response to the California Gold Rush of 1849. Luigi continued in gold during the 1860s and returned to Italy in 1869 to marry Virginia, bringing her to the US and settling in San Jose. Luigi Giannini purchased a 40-acre (16 ha) farm at Alviso in 1872 and grew fruits and vegetables for sale. Four years later, Luigi Giannini was fatally shot by an employee over a pay dispute. His widow Virginia, with two children and pregnant with a third child, took over operation of the produce business. In 1880, Virginia married Lorenzo Scatena (1859–1930) who began L. Scatena & Co. (which A.P. Giannini would eventually take over). Giannini attended Heald College but realized he could do better in business than at school. In 1885, he dropped out and took a full-time position as a produce broker for L. Scatena & Co.[4]

Giannini worked as a produce broker, commission merchant and produce dealer for farms in the Santa Clara Valley. He was successful in that business. He married Clorinda Cuneo (1866–1949), daughter of a North Beach, San Francisco real estate magnate, in 1892 and eventually sold his interest to his employees and retired at the age of 31 to administer his father-in-law's estate.

He later became a director of the Columbus Savings & Loan, in which his father-in-law owned an interest. Giannini observed an opportunity to service the increasing immigrant population that were without a bank. At loggerheads with the other directors who did not share his sentiment, he quit the board in frustration and started his own bank.[5]

He was one of the original Board of Directors of the Italian Board of Relief, now known as Italian Community Services, founded in 1916. It is a non-profit organization focused on serving the Italian and Italian-American community.

Bank of Italy

editGiannini founded the Bank of Italy in the Jackson Square neighborhood of San Francisco on October 17, 1904.[6] The bank was based in a converted saloon as an institution for the "little fellow". It was a new bank for the hardworking immigrants other banks would not serve. Deposits on the first day totaled $8,780.[7] Within a year, deposits soared above $700,000 ($20.4 million in 2020 dollars). The 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fires leveled much of the city. In the face of widespread devastation, Giannini set up a temporary bank, collecting deposits, making loans, and proclaiming that San Francisco would rise from the ashes.[8][9]

Immediately after the earthquake, but before the approaching fire burned the city, he moved the vault's money to his home outside the fire zone in then-rural San Mateo, 18 miles (29 km) away.[10] A garbage wagon was used to haul the money, hidden beneath garbage. The fires had heated the vaults of other big banks, so that the sudden temperature change from opening them risked destroying the contents; many vaults were kept closed for weeks. During this period Giannini was one of the few bankers who could satisfy withdrawal requests and provide loans, operating from a plank across two barrels in the street. Giannini made loans on a handshake to those interested in rebuilding. Years later, he would recount that every loan was repaid. As a reward to the garbage man whose wagon transported the bank's assets, Giannini gave the man's son his first job when he turned 14.[11]

Branch banking was introduced by Giannini shortly after 1909 legislation that allowed branch banking in California. Its first branch outside San Francisco was established in 1909 in San Jose. By 1916, Giannini had expanded and opened several other branches. Giannini believed in branch banking as a way to stabilize banks during difficult times as well as expand the capital base. He bought banks throughout California and eventually Bank of Italy had hundreds of branches throughout the state.[12]

Bank of America

editBank of America, Los Angeles had been established in 1923 by Orra E. Monnette. Giannini began investing in the Bank of America, Los Angeles because conservative business leaders in Los Angeles were less receptive to the Bank of Italy than San Franciscans had been. Bank of America, L.A. represented a growth path for Giannini, and Monnette, president and chairman of the board, was receptive to Giannini's investments. Upon finalizing the merger, Giannini and Monnette concurred that the Bank of America name idealized the broader mission of the new bank. By 1929, the bank had over 400 banking offices in California. The new institution continued under Giannini's chairmanship until his retirement in 1945; Monnette retained his board seat and officer's position. Furthermore, as a condition of the merger, Monnette was paid for handing Giannini the "Foundation Story" rights to the bank, a decision that Monnette later came to regret. Prior to Monnette's creation of the Bank of America Los Angeles network, most banks were limited to a single city or region. Monnette was the first to create a system of centralized processing, bookkeeping and cash delivery. By diversifying the scope of community that the Bank of America served following its merger, the institution was better prepared to ride out minor, local economic issues.[13][14]

Film industry and wine industry

editGiannini helped nurture the motion picture and wine industries in California. He loaned Walt Disney the funds to produce Snow White, the first full-length, animated motion picture to be made in the US. During the Great Depression, he bought the bonds that financed the construction of the Golden Gate Bridge. During World War II, he bankrolled industrialist Henry Kaiser and his enterprises supporting the war effort. After the war, he visited Italy and arranged for loans to help rebuild the war-torn Fiat factories. Giannini also provided capital to William Hewlett and David Packard to help form Hewlett-Packard.

Transamerica Corporation

editGiannini founded another company, Transamerica Corporation, as a holding company for his various interests, including Occidental Life Insurance Company. At one time, Transamerica was the controlling shareholder in Bank of America. They were separated by legislation enacted by the U.S. Congress in 1956, with the passage of the Bank Holding Company Act, which prohibited bank holding companies' involvement in industrial activities.[15]

Politics

editGiannini had long been a Republican, but with the collapse of the Republican Party in the Great Depression, he concerned himself with Democratic state politics. In the 1934 California gubernatorial election Giannini worked hard to block left-wing novelist Upton Sinclair from winning the primary for the Democratic nomination. He failed, and with support from the White House, he endorsed and helped finance the Republican candidate, incumbent Frank Merriam, who did defeat Sinclair.[16]

Death

editUpon Giannini's death in 1949, his son Mario Giannini (1894–1952) assumed leadership of the bank before passing away in 1952.[17] Giannini's daughter, Claire Giannini Hoffman (1905–1997), took her father's seat on the bank's board of directors, where she remained until resigning in 1985.[18] Giannini is buried at Holy Cross Cemetery in Colma, California.[19]

His son Mario had two daughters, Virginia Hammerness and Anne Giannini McWilliams. Virginia spoke publicly about the bank in 2009.[20]

Legacy

edit- His San Mateo estate, "Seven Oaks", purchased in the early 1900s, was located at 20 El Cerrito Avenue, San Mateo, and is now part of the National Register of Historic Places.[10][21]

- The large plaza of the Bank of America Building, at California Street and Kearny, in downtown San Francisco, is named for and in honor of Giannini.

- A.P. Giannini Middle School, which opened in the Sunset District of San Francisco in 1954, is named after him also.[22] Other places and groups named after Giannini include The Giannini Foundation of Agricultural Economics and the building that houses the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, at the University of California, Berkeley.

- Tony Martin was cast as Giannini in the 1962 episode "The Unshakeable Man" of the syndicated anthology series Death Valley Days, hosted by Stanley Andrews. The episode is a dramatization of the establishment of the Bank of America. The story line focuses on Giannini saving his bank from the impact of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and turning it into the largest financial institution in the world. The episode also starred Parley Baer as Crowder.[23]

- There is a 1963 mosaic mural designed by Louis Macouillard and constructed by Alfonso Pardiñas, that illustrates the story of A.P. Giannini's life. Located in front of a mid-century modern style Bank of America branch (formerly a Bank of Italy location) at 300 S. El Camino Real in San Mateo, California.[24][25]

- In 1963, he was inducted into the Hall of Great Westerners of the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.[26]

- The U.S. Postal Service honored Giannini's contributions to American banking by issuing a 21¢ postage stamp bearing his portrait, in 1973. A ceremony to mark the occasion was held near his former home, in San Mateo.

- Time magazine named Giannini one of the "builders and titans" of the 20th century. He was the only banker named to the Time 100, a list of the most important people of that century, as assembled by the magazine.

- Walter Huston's bank president in Frank Capra's 1932 film American Madness was based largely on Giannini.[27]

- The Italian-American banker played by Edward G. Robinson in House of Strangers (1949), was also loosely based on Giannini.[28]

- American Banker magazine recognized him as one of the five most influential bankers of the 20th century.[citation needed]

- In 2004, the Italian government honored Giannini with an exhibition and ceremony in its Parliament, to mark the centennial of his founding of the Bank of Italy. The exhibition was the result of the collaboration of the Ministry of Finance, the Smithsonian Institution, Italian Professor Guido Crapanzano and Peter F. De Nicola, an American collector of Giannini memorabilia.[citation needed]

- In 2010, Giannini was inducted into the California Hall of Fame.[29]

References

edit- ^ "Who Made America?: A.P. Giannini". PBS. Retrieved December 21, 2014.

- ^ "Amadeo Gianini | American Experience | PBS". www.pbs.org. Archived from the original on March 9, 2024. Retrieved 2024-10-07.

- ^ Svanevik, Michael; Burgett, Shirley (2017-10-05). "Matters Historical: How a clever young Italian-American created a powerful bank". The Mercury News. Archived from the original on September 22, 2019. Retrieved 2024-10-07.

- ^ "A.P. Giannini: an Italian American entrepreneur". My Italian Family. September 5, 2015. Archived from the original on January 31, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- ^ Daniel Kadlec (December 7, 1998). "Amadeo Pietro Giannini (1870 ~ 1949)". ganino.com. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- ^ Richards, Rand (2002). Historic Walks in San Francisco: 18 Trails Through the City's Past. Heritage House Publishers. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-879367-03-6.

- ^ James, Marquis & Bessie R. (1954). Biography of a Bank – The Story of Bank of America N.T. & S.A.. Harper & Brothers. p. 16.

- ^ "Amadeo Peter Giannini". californiamuseum.org. Archived from the original on January 31, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- ^ Daven Hiskey (June 24, 2011). "The Real Life "George Bailey" Who Founded Bank of Italy which Became Bank of America". Daily Knowledge Newsletter. Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- ^ a b "Bank of America founder Amadeo Giannini's San Mateo home". SFGate. Retrieved 2017-12-06.

- ^ "Italian American Hero – A.P. Giannini" (PDF). Italian Cultural Center. Volume 29 no. 2. April 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 22, 2018. Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- ^ Alex McCalla & Warren Johnston. "A.P.Giannini: His Legacyto CaliforniaAgriculture" (PDF). University of California. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 12, 2014. Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- ^ Ira Brown Cross, Financing an empire: history of banking in California (The S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1927), pp. 318, 330 and 370.

- ^ "A.P. Giannini (Founder of Bank of America)". bhaskarreddykonda. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- ^ "Transamerica History". Archived from the original on November 25, 2015. Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- ^ Richard Antognini, "The Role of AP Giannini in the 1934 California Gubernatorial Election." Southern California Quarterly 57.1 (1975): 53-86 online.

- ^ Writer, J.L. Pimsleur, Chronicle Staff. "BofA Scion, Board's 1st Female, Dies / Claire Giannini Hoffman was daughter of founder". SFGATE. Retrieved 2024-04-22.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Broder, John M. (1985-03-08). "B of A Founder's Daughter Resigns : Quits Honorary Board Post, Raps Management". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2024-04-22.

- ^ Lee E. Johnson & C. W. Taylor (1953). "Lawrence Mario Giannini". Eminent Californians. Pages 111–112, C. W. Taylor Publ., Palo Alto, California. Archived from the original on September 15, 2015. Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- ^ "A Time When Bankers Were Heroes to Public". ABC News. Retrieved 2024-04-22.

- ^ "National Register #99001181: Seven Oaks in San Mateo, California". noehill.com. Retrieved 2021-03-30.

- ^ "History". A. P. Giannini Middle School. Archived from the original on December 22, 2014. Retrieved December 21, 2014.

- ^ "The Unshakeable Man on Death Valley Days". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved September 17, 2018.

- ^ "California Bucket List". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 2017-12-06.

- ^ Weinstein, Dave (2014-09-12). "Design Destination: Macouillard's Mosaic". The Eichler Network. Retrieved 2017-12-06.

- ^ "Hall of Great Westerners". National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. Retrieved November 22, 2019.

- ^ Maria Laurino (2014). The Italian Americans: A History. W. W. Norton. p. 95. ISBN 9780393241969.

- ^ Eric Martone (2016). Italian Americans: The History and Culture of a People. ABC-CLIO. p. 109. ISBN 9781610699952.

- ^ "Zuckerberg, Doerr among California Hall of Fame inductees". The Mercury News. 2010-07-07. Retrieved 2017-12-06.

Further reading

edit- Antognini, Richard. "The Role of A.P. Giannini in the 1934 California Gubernatorial Election." Southern California Quarterly 57.1 (1975): 53–86. online

- Bonadio, Felice A. (1994) A.P. Giannini: Banker of America (Berkeley: University of California Press) ISBN 0-520-08249-4

- Dana, Julian (1947) A.P. Giannini: A Giant in the West (Prentice-Hall)

- James, Marquis (1954) Biography of a Bank; the story of Bank of America N.T. & S.A (Westport, Conn., Greenwood Press)

- Josephson, Matthew (1972) The Money Lords; the great finance capitalists, 1925–1950 (New York, Weybright and Talley)

- Nash, Gerald D. (1992) A.P. Giannini and the Bank of America (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press) ISBN 9780806124612

External links

edit- Works by or about Amadeo Giannini at the Internet Archive

- "Time Magazine's profile of Amadeo Giannini". Archived from the original on 2007-01-21. Retrieved 2006-11-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - A.P. Giannini, Marriner Stoddard Eccles, and The Changing Landscape of American Banking

- A collection of works by Amadeo Giannini

- Newspaper clippings about Amadeo Giannini in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- Amadeo Pietro "A.P." Giannini at Find a Grave[1]