Heathenry is a modern Pagan new religious movement that has been active in the United States since at least the early 1970s. Although the term "Heathenry" is often employed to cover the entire religious movement, different Heathen groups within the United States often prefer the term "Ásatrú" or "Odinism" as self-designations.

Heathenry appeared in the United States during the 1960s, at the same time as the wider emergence of modern Paganism in the United States. Among the earliest American group was the Odinist Fellowship, founded by Danish migrant Else Christensen in 1969.

History

editÁsatrú grew steadily in the United States during the 1960s.[1] In 1969, the Danish Odinist Else Christensen established the Odinist Fellowship from her home in Florida.[2] Heavily influenced by Alexander Rud Mills' writings,[3] she began publication of a magazine, The Odinist,[4] although this focused to a greater extent on right-wing and racialist ideas than theological ones.[5] Stephen McNallen first founded the Viking Brotherhood in the early 1970s, before creating the Ásatrú Free Assembly (AFA) in 1976, which broke up in 1986 amid widespread political disagreements after McNallen's repudiation of neo-Nazis within the group. In the 1990s, McNallen founded the Ásatrú Folk Assembly (AFA), an ethnically oriented Heathen group headquartered in California.[6]

Meanwhile, Valgard Murray and his kindred in Arizona founded the Ásatrú Alliance (AA) in the late 1980s, which shared the AFA's perspectives on race and which published the Vor Tru newsletter.[7] In 1987, Edred Thorsson and James Chisholm founded The Troth, which was incorporated in Texas. Taking an inclusive, non-racialist view, it soon grew into an international organisation.[8]

Terminology

editIn English usage, the genitive Ásatrúar "of Æsir faith" is often used on its own to denote adherents (both singular and plural).[9] This term is favored by practitioners who focus on the deities of Scandinavia,[10] although it is problematic as many Asatruar worship deities and entities other than the Æsir, such as the Vanir, Valkyries, Elves, and Dwarves.[11] Other practitioners term their religion Vanatrú, meaning "those who honour the Vanir" or Dísitrú, meaning "those who honour the Goddesses", depending on their particular theological emphasis.[12]

Within the community it is sometimes stated that the term Ásatrú pertains to groups which are not racially focused, while Odinism is the term preferred by racially oriented groups. However, in practice, there is no such neat division in terminology.[13]

There are notable differences of emphasis between Ásatrú as practiced in the US and in Scandinavia. According to Strmiska & Sigurvinsson (2005), American Asatruar tend to prefer a more devotional form of worship and a more emotional conception of the Nordic gods than Scandinavian practitioners, reflecting the parallel tendency of highly emotional forms of Christianity prevalent in the United States.[14]

Demographics

editAlthough deeming it impossible to calculate the exact size of the Heathen community in the US, sociologist Jeffrey Kaplan estimated that, in the mid-1990s, there were around 500 active practitioners in the country, with a further thousand individuals on the periphery of the movement.[15] He noted that the overwhelming majority of individuals in the movement were white, male, and young. Most had at least an undergraduate degree, and worked in a mix of white collar and blue collar jobs.[16] From her experience within the community, Snook concurred that the majority of American Heathens were male, adding also that most were also white and middle-aged,[17] but believed that there had been a growth in the proportion of Heathen women in the US since the mid-1990s.[18]

In 2003, the Pagan Census Project led by Helen A. Berger, Evan A. Leach, and Leigh S. Shaffer gained 60 responses from Heathens in the US, noting that 65% were male and 35% female, which they saw as the "opposite" of the rest of the country's Pagan community.[19] The majority had a college education, but were generally less well educated than the wider Pagan community, with a lower median income than the wider Pagan community too.[19]

Politics and controversies

editÁsatrú organizations have memberships which span the entire political and spiritual spectrum. There is a history of political controversy within organized US Ásatrú, mostly surrounding the question of how to deal with such adherents as place themselves in a context of the far right and white supremacy, notably resulting in the fragmentation of the Asatru Free Assembly in 1986.

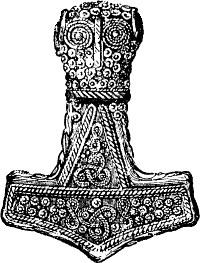

Externally, political activity on the part of Ásatrú organizations has surrounded campaigns against alleged religious discrimination, such as the call for the introduction of an Ásatrú "emblem of belief" by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs to parallel the Wiccan pentacle granted to the widow of Patrick Stewart in 2006. In May 2013, the "Hammer of Thor" was added to the list of United States Department of Veterans Affairs emblems for headstones and markers.[20][21] It was reported in early 2019 that a Heathenry service was held on the U.S. Navy's USS John C. Stennis[22]

Folkish Ásatrú, Universalism and racialism

editHistorically, the main dispute between the national organizations has generally centered on the interpretation of "Nordic heritage" as either something cultural, or as something genetic or racial. In the internal discourse within American Ásatrú, this cultural/racial divide has long been known as "universalist" vs. "folkish" Ásatrú.[23]

The Troth takes the "universalist" position, claiming Ásatrú as a synonym for "Northern European Heathenry" taken to comprise "many variations, names, and practices, including Theodism, Irminism, Odinism, and Anglo-Saxon Heathenry". The Asatru Folk Assembly takes the folkish position, claiming that Ásatrú and the Germanic beliefs are ancestral in nature, and as an indigenous religion of the European Folk should only be accessed by the descendants of Europe. In the UK, Germanic Neopaganism is more commonly known as Odinism or as Heathenry. This is mostly a matter of terminology, and US Ásatrú may be equated with UK Odinism for practical purposes, as is evident in the short-lived International Asatru-Odinic Alliance of folkish Ásatrú/Odinist groups.

Some groups identifying as Ásatrú have been associated with national socialist and white nationalist movements.[24] Wotansvolk, for example, is an explicitly racial form.

More recently, however, many Ásatrú groups have been taking a harder stance against these elements of their community. Declaration 127, so named for the corresponding stanza of the Hávamál: "When you see misdeeds, speak out against them, and give your enemies no frið” is a collective statement denouncing and testifying disassociation with the Asatru Folk Assembly for alleged racial and sexually-discriminatory practices and beliefs signed by over 150 Ásatrú religious organizations from over 15 different nations mainly represented on Facebook.[citation needed]

Discrimination charges

editInmates of the "Intensive Management Unit" at Washington State Penitentiary who are adherents of Ásatrú in 2001 were deprived of their Thor's Hammer medallions.[25][unreliable source?] In 2007, a federal judge confirmed that Ásatrú adherents in US prisons have the right to possess a Thor's Hammer pendant. An inmate sued the Virginia Department of Corrections after he was denied it while members of other religions were allowed their medallions.[26]

In the Georgacarakos v. Watts case Peter N. Georgacarakos filed a pro se civil-rights complaint in the United States District Court for the District of Colorado against 19 prison officials for "interference with the free exercise of his Ásatrú religion" and "discrimination on the basis of his being Ásatrú".[27]

See also

editReferences

editFootnotes

edit- ^ Paxson 2002, p. 17.

- ^ Gardell 2003, p. 165; Asprem 2008, p. 46.

- ^ Gardell 2003, pp. 167–168.

- ^ Gardell 2003, p. 171; Asprem 2008, p. 46.

- ^ Kaplan 1996, p. 226; Adler 2006, p. 289.

- ^ Kaplan 1996, pp. 200–205; Paxson 2002, pp. 16–17; Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 128; Adler 2006, p. 286.

- ^ Kaplan 1996, pp. 206–213; Paxson 2002, p. 18.

- ^ Kaplan 1996, pp. 213–215; Paxson 2002, p. 18.

- ^ Blain 2002, p. 5; Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 128; Adler 2006, p. 286; Harvey 2007, p. 53.

- ^ Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 128.

- ^ Strmiska 2000, p. 113.

- ^ Harvey 2007, p. 53.

- ^ Gardell 2003, p. 152.

- ^ "American Nordic Pagans want to feel an intimate relationship with their gods, not unlike evangelical attitudes towards Jesus. Icelandic Asatruar, by contrast, are more focused on devotion to their past cultural heritage rather than to particular gods." Strmiska & Sigurvinsson (2005), p. 165

- ^ Kaplan 1996, p. 198.

- ^ Kaplan 1996, p. 199.

- ^ Snook 2015, p. 24.

- ^ Snook 2015, p. 108.

- ^ a b Berger, Leagh & Shaffer 2003, p. 16.

- ^ "National Cemetery Administration: Available Emblems of Belief for Placement on Government Headstones and Markers". U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

55 – Hammer of Thor

- ^ Elysia. "Hammer of Thor now VA accepted symbol of faith". Llewellyn. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ^ "Heathens hold religious services rooted in Norse paganism aboard aircraft carrier". 7 January 2019.

- ^ Strmiska & Sigurvinsson 2005, p. 134f.

- ^ Gardell 2003, pp. 269–283.

- ^ "Walla Walla's Suppression of Religious Freedom".

- ^ First Amendment Center: Va. inmate can challenge denial of Thor's Hammer Archived 2010-10-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "05-1180 -- Georgacarakos v. Watts -- 08/18/2005".

Sources

edit- Adler, Margot (2006) [1979]. Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshipers and Other Pagans in America (revised ed.). London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-303819-1.

- Asprem, Egil (2008). "Heathens Up North: Politics, Polemics, and Contemporary Paganism in Norway". The Pomegranate: The International Journal of Pagan Studies. 10 (1): 42–69. doi:10.1558/pome.v10i1.41.

- Berger, Helen A.; Leagh, Evan A.; Shaffer, Leigh S. (2003). Voices from the Pagan Census: A National Survey of Witches and Neo-Pagans in the United States. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-488-6.

- Blain, Jenny (2002). Nine Worlds of Seidr-Magic: Ecstasy and Neo-Shamanism in North European Paganism. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-25651-3.

- Davy, Barbara Jane (2007). Introduction to Pagan Studies. Lanham: AltaMira. ISBN 978-0-7591-0819-6.

- Gardell, Matthias (2003). Gods of the Blood: The Pagan Revival and White Separatism. Durham and London: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-3071-4.

- Harvey, Graham (2007). Listening People, Speaking Earth: Contemporary Paganism (second ed.). London: Hurst & Company. ISBN 978-1-85065-272-4.

- Kaplan, Jeffrey (1996). "The Reconstruction of the Ásatrú and Odinist Traditions". In Lewis, James R. (ed.). Magical Religion and Modern Witchcraft. New York: State University of New York. pp. 193–236. ISBN 978-0-7914-2890-0.

- Kaplan, Jeffrey (1997). Radical Religion in America: Millenarian Movements from the Far Right to the Children of Noah. Syracuse: Syracuse Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-0396-2.

- Paxson D (2002). "Asatru in the United States". In Rabinovitch S, Lewis J (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Modern Witchcraft and Neo-Paganism. New York: Citadel Press. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-0-8065-2406-1.

- Pizza, Murphy (2014). Paganistan: Contemporary Pagan Community in Minnesota's Twin Cities. Farnham: Ashgate. ISBN 978-1-4094-4283-7.

- Snook, Jennifer (2015). American Heathens: The Politics of Identity in a Pagan Religious Movement. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-4399-1097-9.

- Strmiska, Michael F. (2000). "Ásatrú in Iceland: The Rebirth of Nordic Paganism". Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions. 4 (1): 106–132. doi:10.1525/nr.2000.4.1.106.

- Strmiska, Michael F.; Sigurvinsson, Baldur A. (2005). "Asatru: Nordic Paganism in Iceland and America". In Strmiska, Michael F. (ed.). Modern Paganism in World Cultures. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 127–179. ISBN 978-1-85109-608-4.

External links

edit- Paulas, Rick; How a Thor-Worshipping Religion Turned Racist, Vice Magazine, May 1, 2015

- Ásatrú (Germanic Paganism) – ReligionFacts

- Asatru (Norse Heathenism) Archived 2007-10-16 at the Wayback Machine – AltReligion

- Ásatrú (Norse Heathenism) Archived 2015-01-10 at the Wayback Machine – Religioustolerance

- Jotun's Bane Kindred

- Ravencast – The Only Asatru Podcast – Interviews and 101 Information

- On the development of Ásatrú in Australia see: Jøn, A. Asbjørn (1999). "'Skeggöld, skálmöld; vindöld, vergöld' - Alexander Rud Mills and the Ásatrú faith in the New Age". Australian Religion Studies Review (12). University of Sydney: 77–83. Retrieved 30 October 2015.