A satiric misspelling is an intentional misspelling of a word, phrase or name for a rhetorical purpose. This can be achieved with intentional malapropism (e.g. replacing erection for election), enallage (giving a sentence the wrong form, eg. "we was robbed!"), or simply replacing a letter with another letter (for example, in English, k replacing c), or symbol ($ replacing s). Satiric misspelling is found widely today in informal writing on the Internet, but is also made in some serious political writing that opposes the status quo.

K replacing c

editIn political writing

editReplacing the letter c with k in the first letter of a word was used by the Ku Klux Klan during its early years in the mid-to-late 19th century. The concept is continued today within the group. For something similar in the writing of groups opposed to the KKK, see § KKK replacing c or k, below.

In the 1960s and early 1970s in the United States, the Yippies sometimes used Amerika rather than America in referring to the United States.[1][2][3] According to Oxford Dictionaries, it was an allusion to the Russian and German spellings of the word and intended to be suggestive of fascism and authoritarianism.[1]

A similar usage in Italian, Spanish, Catalan and Portuguese[citation needed] is to write okupa rather than ocupa (often on a building or area occupied by squatters),[4][better source needed] referring to the name adopted by okupación activist groups. It stems from a combination of English borrowings with k in them to those languages, and Spanish anarchist and punk movements which used "k" to signal rebellion.[5]

In humor

editReplacing "c" with "k" was at the center of a Monty Python joke from the Travel Agent sketch. Eric Idle's character has an affliction that makes him pronounce the letter C as a B, as in "blassified" instead of "classified". Michael Palin asks him if he can say the letter K; Idle replies that he can, and Palin suggests that he spell words with a K instead of C. Idle replies: "what, you mean, pronounce 'blassified' with a K? [...] Klassified. [...] Oh, it's very good! I never thought of that before! What a silly bunt!"[6]

KKK replacing c or k

editA common satiric usage of the letters KKK is the spelling of America as Amerikkka, alluding to the Ku Klux Klan, referring to underlying racism in American society. The earliest known usage of Amerikkka recorded in the Oxford English Dictionary is in July 1970, in an African-American magazine called Black World.[7]

The spelling Amerikkka came into greater use after the 1990 release of the gangsta rap album AmeriKKKa's Most Wanted by Ice Cube. The letters KKK have been inserted into several other words and names, to indicate similar perceived racism, oppression or corruption. Examples include:

- Republikkkan (U.S. Republican Party)[8]

- Demokkkrat (U.S. Democratic Party)[9]

- KKKapitalism (capitalism)[10]

- David DuKKKe (David Duke),[11] former Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, candidate for United States Senate, candidate for Governor of Louisiana, and antisemitic conspiracy theorist

Currency signs

editCurrency symbols like €, $ and £ can be inserted in place of the letters E, S and L respectively to indicate plutocracy, greed, corruption, or the perceived immoral, unethical, or pathological accumulation of money. For example:

- Bu$h (for George W. Bush, George H. W. Bush, or the Bush family)[12][13][14]

- Congre$$ (for United States Congress)[15]

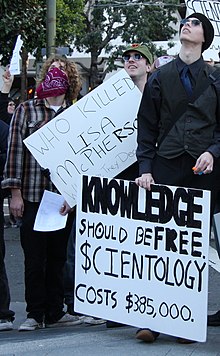

- Co$ or $cientology (for the Church of Scientology):[16][17] see also Scientology controversies.

- Di$ney and Di$neyland (for The Walt Disney Company and Disneyland):[18] see also Criticism of the Walt Disney Company and Disneyland § Tickets

- E$$o (for Esso): Used by the UK-based Stop Esso campaign encouraging people to boycott Esso, in protest against Esso's opposition to the Kyoto Protocol.[19]

- €urope (for Europe)[20]

- Ke$ha (singer-songwriter): adopted the dollar sign in her name while financially struggling as an ironic gesture.[21]

- Micro$oft, M$, M$FT (for Microsoft):[22][23] see also Criticism of Microsoft

- $ony (for Sony)[24][25]

- United $tates (for the United States)[26]

- £$€ for the London School of Economics[citation needed]

Word-in-word

editOccasionally a word written in its orthodox spelling is altered with internal capital letters, hyphens, italics, or other devices so as to highlight a fortuitous pun. Some examples:

- After the controversial 2000 United States presidential election, the alleged improprieties of the election prompted the use of such titles as "pResident" and "(p)resident" for George W. Bush.[27] The same effects were also used for Bill Clinton during and after Clinton's impeachment hearings.[citation needed] These devices were intended to suggest that the president was merely the resident of the White House rather than the legitimate leader.[27]

- The controversial United States law USA PATRIOT Act is sometimes called "USA PAT RIOT Act" or "(Pat)Riot Act" by its opponents.[28][29] This is done to avoid using the common term Patriot Act, which implies the law is patriotic.[28]

- Feminist theologian Mary Daly has used a slash to make a point about patriarchy: "gyn/ecology", "stag/nation", "the/rapist".[30]

- In French, where con is an insulting word meaning "moron", the word conservateur (conservative) has been written "con-servateur",[31] "con... servateur",[32] or "con(servateur)".[33] The American English term neo-con, an abbreviation of neo-conservative, becomes a convenient pun when used in French.[34] In English, the first syllable of conservative can be emphasized to suggest a con artist.[35]

- Netizens often called Senator Ramon "Bong" Revilla Jr. as "MandaramBONG" (Filipino word for plunderer) to highlight allegations that he pocketed pork barrel funds through the use of fake non-government organizations.[36]

- Jair Bolsonaro has been called BolsoNero, due to the 2019 Amazon rainforest wildfires and indifference to the COVID-19 pandemic.[37][38]

In internet memes

editLolcats

editIn the mid-2000s, lolcat image macros were captioned with deliberate misspellings, known as "lolspeak", such as a cat asking "I can haz cheezburger?"[39] Blogger Anil Dash described the intentionally poor spelling and fractured grammar as "kitty pidgin".[39]

"B" emoji replacing hard consonants

editThe negative squared letter B (🅱️; originally used to represent blood type B)[40] can be used to replace hard consonants as an internet meme. This originates from the practice of members of the Bloods replacing the letter C with the letter B, but has been extended to any consonant.[41][42] Common examples are:

- Ni🅱️🅱️a, replacing nigga.[41] Some non-black people have been criticised for using this as if the taboo around the word did not apply.[41]

- 🅱️loods for Bloods.[41]

- 🅱️eter for Peter Griffin.[41]

Misspelled animal names

editVarious different instances of intentional misspellings of animal names have been made as internet memes. The mid-2000s lolcat memes used spellings such as kitteh for kitty.[43]

The 2013 Doge meme is a deliberate misspelling of dog.[44]

The internet slang of DoggoLingo, which appeared around the same time, spells dog as doggo and also includes respelled words for puppy (pupper) and other animals such as bird (birb) and snake (snek).[45] Respellings in DoggoLingo usually alter the pronunciation of the word.

Other significant respellings

editAlong the same lines, intentional misspellings can be used to promote a specific negative attribute, real or perceived, of a product or service. This is especially effective if the misspelling is done by replacing part of the word with another that has identical phonetic qualities.

Journalists may make a politicized editorial decision by choosing to differentially retain (or even create) misspellings, mispronunciations, ungrammaticisms, dialect variants, or interjections.

The British political satire magazine Private Eye has a long-standing theme of insulting the law firm Carter-Ruck by replacing the R with an F to read Carter-Fuck. The law firm once requested that Private Eye cease spelling its name like that; the magazine then started spelling it "Farter-Fuck".[46] Likewise, Private Eye often refers to The Guardian as The Grauniad,[47] due to the newspaper's early reputation for typographical errors.[48]

Backronyms

editPlays on acronyms and initialisms are also common, when the full name is spelled out but one of the component words is replaced by another. For example, Richard Stallman and other Free Software Foundation executives often refer to digital rights management as "digital restrictions management".[49] a reference to the tendency for DRM to stifle the end user's ability to reshare music or write CDs more than a certain number of times. Likewise, the National Security Agency is often referred to as the "National Surveillance Agency"[50][51][52][53] and sometimes "National Socialist Agency"[54][55] by opponents of its PRISM program, who view it as dystopian encroachment on personal privacy.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "Amerika | Meaning of Amerika by Lexico". Lexico Dictionaries | English. Archived from the original on April 2, 2020. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ "Psychedelic 60's: Four Radical Groups". UVA Library. Archived from the original on December 6, 1998. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ Rubin, Jerry. "Jerry Rubin: Self-Portrait of a Child of "Amerika," 1970". american.edu. Archived from the original on November 3, 2003. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ "comunidades.calle22.com - TODOS SOMOS OKUPAS". Archived from the original on June 11, 2008. Retrieved October 7, 2004.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Rodríguez González, Félix (2006). "Medios de comunicación y contracultura juvenil" (PDF). Círculo.

- ^ Monty Python at Hollywood Bowl – The holiday on YouTube.

- ^ "Black World/Negro Digest". Johnson Publishing Company. July 1970.

- ^ "The Blackstripe - Stolen 2000 Election". Archived from the original on February 25, 2006. Retrieved October 8, 2004.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "The Blackstripe - Stolen 2000 Election". Archived from the original on February 25, 2006. Retrieved October 8, 2004.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "From Critical Reflections to Forward Progression". Archived from the original on November 4, 2005. Retrieved 2005-11-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Barkun, Michael (1997). Religion and the Racist Right: The Origins of the Christian Identity Movement (illustrated, revised ed.). UNC Press Books. p. 315. ISBN 9780807846384. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- ^ "«Stoppez Bu$h". Le Devoir. November 20, 2003.

- ^ "Caught in the Crossfire: What Will Bu$h Do About Corporate Corruption?". Archive.democrats.com. June 28, 2002.

- ^ "UK Indymedia - Stop Bu$h - National Demonstration - Thursday 20th". Indymedia.org.uk. November 20, 2003.

- ^ "Congre$$, Heal Thyself". Common Dreams. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ "The $cientology Cartoon Page". Archived from the original on March 2, 2007. Retrieved February 24, 2005.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Scientology LIES to Media doctored photos proof". lermanet.org. Archived from the original on April 2, 2020. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ "JOE MATHEWS: Di$neyland ought to give kids a break". The Bakersfield Californian. December 16, 2014.

- ^ "Interview with a Stop Esso activist". Greenpeace. November 29, 2001. Archived from the original on January 8, 2016. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- ^ "€urope's role in the €nergy €volution". Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ^ "View Single Post - Pop sensation Ke$ha gutsy, fearless". jam.canoe.ca. January 19, 2010. Archived from the original on July 19, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ at 15:00, Richard Speed 21 Aug 2019. "Microsoft: Reckon our code is crap? Prove it and $30k could be yours". www.theregister.co.uk. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "С такими друзьями враги не нужны: обзор топ-смартфона Nokia Lumia 900". ZOOM.CNews.ru (in Russian). Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ "[PS4 Scene] Nem todo herói usa capa! – NewsInside" (in Brazilian Portuguese). March 17, 2020. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ "Ściąganie gier na PS4 będzie wolniejsze - Sony obniża prędkość | GRYOnline.pl". GRY-Online.pl (in Polish). Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ "United $tates". Anti-Imperialism.org. Archived from the original on April 2, 2020. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ a b "Name the President!". The Nation. March 18, 2006. Archived from the original on May 30, 2006.

- ^ a b "PAT RIOT Act - Richard Stallman". Stallman.org. Archived from the original on April 9, 2016. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ Tkacik, John. "Beijing Reads Democracy in Hong Kong the (Pat)Riot Act". The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ Priluck, Jill (March 1999). "Battling stag/nation". Salon Ivory Tower. Archived from the original on January 28, 2005. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ "Elections Québec '98". June 11, 2008. Archived from the original on June 11, 2008.

- ^ "cri". Chantiers.org.

- ^ "France-Mail-Forum Nr. 31: Politique et histoire". June 11, 2008. Archived from the original on June 11, 2008.

- ^ "Les deux vies de " Wolfie ", le " néo-con " au " coeur qui saigne". LeMonde.fr.

- ^ Jane Kleeb (July 2, 2010). ""Con"servative Bait and Switch". Boldnebraska.org. Archived from the original on April 2, 2012. Retrieved 2012-04-30.

- ^ "'MandaramBong': Netizens twit Revilla speech". ABS-CBN News. January 20, 2014.

- ^ "BolsoNERO, Brazil's President Fiddles as a Pandemic Looms". The Economist. March 26, 2020.

- ^ "As Amazon Rainforest Burns, Indigenous Women Call on Support". Indian Country Today. August 23, 2019.

- ^ a b Silverman, Dwight (June 5, 2007). "Web photo phenomenon centers on felines, poor spelling". Chron. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ "🅱️ Negative Squared Latin Capital Letter B Emoji". emojipedia.org. Retrieved September 21, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Hathaway, Jay (June 16, 2017). "Behind B Emoji, the Meme Tearing the Internet Apart". The Daily Dot. Archived from the original on June 17, 2017. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ Smith, Debra; Whitmore, Kathryn F. (2006). Literacy and Advocacy in Adolescent Family, Gang, School, and Juvenile Court Communities. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-8058-5599-8.

- ^ Geier, Thom, et al. (December 11, 2009). "The 100 Greatest Movies, TV shows, Albums, Books, Characters, Scenes, Episodes, Songs, Dresses, Music Videos, and Trends that entertained us over the past 10 Years ". Entertainment Weekly. (1079/1080):74-84

- ^ "Doge". KnowYourMeme.com. July 24, 2013. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

- ^ Chidester, Tegan (March 12, 2020). "Doggolingo: A Guide to the Internet's Favorite Language". OutwardHound.com. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

- ^ "Peter Carter-Ruck". The Daily Telegraph. London. December 22, 2003. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ^ Sherrin, Ned (December 16, 2000). "Surely shome mishtake?". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Bernhard, Jim (2007). Porcupine, Picayune, & Post: how newspapers get their names. University of Missouri Press. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-0-8262-1748-6. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- ^ "Opposing Digital Rights Mismanagement (Or Digital Restrictions Management, as we now call it)?". Retrieved May 29, 2014.

- ^ "National 'Surveillance' Agency? Audit reveals NSA violations". Fox News. February 4, 2017.

- ^ "National Surveillance Agency: Looking At Google Glass, Xbox One Through The NSA's Prism [OPINION]". iDigitalTimes.com. June 14, 2013. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013.

- ^ "National Surveillance Agency: Looking At Google Glass, Xbox One Through The NSA's Prism". n4g.com.

- ^ Catholic Online. "National Surveillance Agency program is still ongoing". catholic.org. Archived from the original on December 25, 2013.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on March 12, 2016. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Barry Popik".

External links

edit- On de spelling and use of various words by Mangwiro A. Sadiki-Yisrael