Amicable numbers are two different natural numbers related in such a way that the sum of the proper divisors of each is equal to the other number. That is, s(a)=b and s(b)=a, where s(n)=σ(n)-n is equal to the sum of positive divisors of n except n itself (see also divisor function).

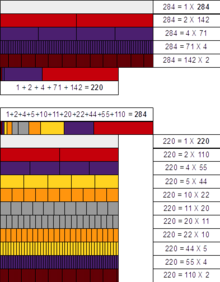

The smallest pair of amicable numbers is (220, 284). They are amicable because the proper divisors of 220 are 1, 2, 4, 5, 10, 11, 20, 22, 44, 55 and 110, of which the sum is 284; and the proper divisors of 284 are 1, 2, 4, 71 and 142, of which the sum is 220.

The first ten amicable pairs are: (220, 284), (1184, 1210), (2620, 2924), (5020, 5564), (6232, 6368), (10744, 10856), (12285, 14595), (17296, 18416), (63020, 76084), and (66928, 66992). (sequence A259180 in the OEIS). (Also see OEIS: A002025 and OEIS: A002046) It is unknown if there are infinitely many pairs of amicable numbers.

A pair of amicable numbers constitutes an aliquot sequence of period 2. A related concept is that of a perfect number, which is a number that equals the sum of its own proper divisors, in other words a number which forms an aliquot sequence of period 1. Numbers that are members of an aliquot sequence with period greater than 2 are known as sociable numbers.

History

editAmicable numbers were known to the Pythagoreans, who credited them with many mystical properties. A general formula by which some of these numbers could be derived was invented circa 850 by the Iraqi mathematician Thābit ibn Qurra (826–901). Other Arab mathematicians who studied amicable numbers are al-Majriti (died 1007), al-Baghdadi (980–1037), and al-Fārisī (1260–1320). The Iranian mathematician Muhammad Baqir Yazdi (16th century) discovered the pair (9363584, 9437056), though this has often been attributed to Descartes.[1] Much of the work of Eastern mathematicians in this area has been forgotten.

Thābit ibn Qurra's formula was rediscovered by Fermat (1601–1665) and Descartes (1596–1650), to whom it is sometimes ascribed, and extended by Euler (1707–1783). It was extended further by Borho in 1972. Fermat and Descartes also rediscovered pairs of amicable numbers known to Arab mathematicians. Euler also discovered dozens of new pairs.[2] The second smallest pair, (1184, 1210), was discovered in 1867 by 16-year-old B. Nicolò I. Paganini (not to be confused with the composer and violinist), having been overlooked by earlier mathematicians.[3][4]

| # | m | n |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 220 | 284 |

| 2 | 1,184 | 1,210 |

| 3 | 2,620 | 2,924 |

| 4 | 5,020 | 5,564 |

| 5 | 6,232 | 6,368 |

| 6 | 10,744 | 10,856 |

| 7 | 12,285 | 14,595 |

| 8 | 17,296 | 18,416 |

| 9 | 63,020 | 76,084 |

| 10 | 66,928 | 66,992 |

There are over 1,000,000,000 known amicable pairs.[5]

Rules for generation

editWhile these rules do generate some pairs of amicable numbers, many other pairs are known, so these rules are by no means comprehensive.

In particular, the two rules below produce only even amicable pairs, so they are of no interest for the open problem of finding amicable pairs coprime to 210 = 2·3·5·7, while over 1000 pairs coprime to 30 = 2·3·5 are known [García, Pedersen & te Riele (2003), Sándor & Crstici (2004)].

Thābit ibn Qurrah theorem

editThe Thābit ibn Qurrah theorem is a method for discovering amicable numbers invented in the 9th century by the Arab mathematician Thābit ibn Qurrah.[6]

It states that if

where n > 1 is an integer and p, q, r are prime numbers, then 2n × p × q and 2n × r are a pair of amicable numbers. This formula gives the pairs (220, 284) for n = 2, (17296, 18416) for n = 4, and (9363584, 9437056) for n = 7, but no other such pairs are known. Numbers of the form 3 × 2n − 1 are known as Thabit numbers. In order for Ibn Qurrah's formula to produce an amicable pair, two consecutive Thabit numbers must be prime; this severely restricts the possible values of n.

To establish the theorem, Thâbit ibn Qurra proved nine lemmas divided into two groups. The first three lemmas deal with the determination of the aliquot parts of a natural integer. The second group of lemmas deals more specifically with the formation of perfect, abundant and deficient numbers.[6]

Euler's rule

editEuler's rule is a generalization of the Thâbit ibn Qurra theorem. It states that if where n > m > 0 are integers and p, q, r are prime numbers, then 2n × p × q and 2n × r are a pair of amicable numbers. Thābit ibn Qurra's theorem corresponds to the case m = n − 1. Euler's rule creates additional amicable pairs for (m,n) = (1,8), (29,40) with no others being known. Euler (1747 & 1750) overall found 58 new pairs increasing the number of pairs that were then known to 61.[2][7]

Regular pairs

editLet (m, n) be a pair of amicable numbers with m < n, and write m = gM and n = gN where g is the greatest common divisor of m and n. If M and N are both coprime to g and square free then the pair (m, n) is said to be regular (sequence A215491 in the OEIS); otherwise, it is called irregular or exotic. If (m, n) is regular and M and N have i and j prime factors respectively, then (m, n) is said to be of type (i, j).

For example, with (m, n) = (220, 284), the greatest common divisor is 4 and so M = 55 and N = 71. Therefore, (220, 284) is regular of type (2, 1).

Twin amicable pairs

editAn amicable pair (m, n) is twin if there are no integers between m and n belonging to any other amicable pair (sequence A273259 in the OEIS).

Other results

editIn every known case, the numbers of a pair are either both even or both odd. It is not known whether an even-odd pair of amicable numbers exists, but if it does, the even number must either be a square number or twice one, and the odd number must be a square number. However, amicable numbers where the two members have different smallest prime factors do exist: there are seven such pairs known.[8] Also, every known pair shares at least one common prime factor. It is not known whether a pair of coprime amicable numbers exists, though if any does, the product of the two must be greater than 1065.[9][10] Also, a pair of co-prime amicable numbers cannot be generated by Thabit's formula (above), nor by any similar formula.

In 1955 Paul Erdős showed that the density of amicable numbers, relative to the positive integers, was 0.[11]

In 1968 Martin Gardner noted that most even amicable pairs sumsdivisible by 9,[12] and that a rule for characterizing the exceptions (sequence A291550 in the OEIS) was obtained.[13]

According to the sum of amicable pairs conjecture, as the number of the amicable numbers approaches infinity, the percentage of the sums of the amicable pairs divisible by ten approaches 100% (sequence A291422 in the OEIS). Although all amicable pairs up to 10,000 are even pairs, the proportion of odd amicable pairs increases steadily towards higher numbers, and presumably there are more of them than of the even amicable pairs (A360054 in OEIS).

Gaussian integer amicable pairs exist,[14][15] e.g. s(8008+3960i) = 4232-8280i and s(4232-8280i) = 8008+3960i.[16]

Generalizations

editAmicable tuples

editAmicable numbers satisfy and which can be written together as . This can be generalized to larger tuples, say , where we require

For example, (1980, 2016, 2556) is an amicable triple (sequence A125490 in the OEIS), and (3270960, 3361680, 3461040, 3834000) is an amicable quadruple (sequence A036471 in the OEIS).

Amicable multisets are defined analogously and generalizes this a bit further (sequence A259307 in the OEIS).

Sociable numbers

editSociable numbers are the numbers in cyclic lists of numbers (with a length greater than 2) where each number is the sum of the proper divisors of the preceding number. For example, are sociable numbers of order 4.

Searching for sociable numbers

editThe aliquot sequence can be represented as a directed graph, , for a given integer , where denotes the sum of the proper divisors of .[17] Cycles in represent sociable numbers within the interval . Two special cases are loops that represent perfect numbers and cycles of length two that represent amicable pairs.

References in popular culture

edit- Amicable numbers are featured in the novel The Housekeeper and the Professor by Yōko Ogawa, and in the Japanese film based on it.

- Paul Auster's collection of short stories entitled True Tales of American Life contains a story ('Mathematical Aphrodisiac' by Alex Galt) in which amicable numbers play an important role.

- Amicable numbers are featured briefly in the novel The Stranger House by Reginald Hill.

- Amicable numbers are mentioned in the French novel The Parrot's Theorem by Denis Guedj.

- Amicable numbers are mentioned in the JRPG Persona 4 Golden.

- Amicable numbers are featured in the visual novel Rewrite.

- Amicable numbers (220, 284) are referenced in episode 13 of the 2017 Korean drama Andante.

- Amicable numbers are featured in the Greek movie The Other Me (2016 film).

- Amicable numbers are discussed in the book Are Numbers Real? by Brian Clegg.

- Amicable numbers are mentioned in the 2020 novel Apeirogon by Colum McCann.

See also

edit- Betrothed numbers (quasi-amicable numbers)

- Amicable triple - Three-number variation of Amicable numbers.

Notes

edit- ^ Costello, Patrick (1 May 2002). "New Amicable Pairs Of Type (2; 2) And Type (3; 2)" (PDF). Mathematics of Computation. 72 (241): 489–497. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-02-01414-X. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-02-29. Retrieved 19 April 2007.

- ^ a b Sandifer, C. Edward (2007). How Euler Did It. Mathematical Association of America. pp. 49–55. ISBN 978-0-88385-563-8.

- ^ Sprugnoli, Renzo (27 September 2005). "Introduzione alla matematica: La matematica della scuola media" (PDF) (in Italian). Universita degli Studi di Firenze: Dipartimento di Sistemi e Informatica. p. 59. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ^ Martin Gardner (2020) [Originally published in 1977]. Mathematical Magic Show. American Mathematical Society. p. 168. ISBN 9781470463588. Archived from the original on 2023-09-12. Retrieved 2023-03-18.

- ^ Chernykh, Sergei. "Amicable pairs list". Retrieved 2024-05-28.

- ^ a b Rashed, Roshdi (1994). The development of Arabic mathematics: between arithmetic and algebra. Vol. 156. Dordrecht, Boston, London: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 278,279. ISBN 978-0-7923-2565-9.

- ^ See William Dunham in a video: An Evening with Leonhard Euler – YouTube Archived 2016-05-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Amicable pairs news". Archived from the original on 2021-07-18. Retrieved 2016-01-31.

- ^ Hagis, Peter, Jr. (1969). "On relatively prime odd amicable numbers". Mathematics of Computation. 23 (107): 539–543. doi:10.2307/2004381. JSTOR 2004381. MR 0246816.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hagis, Peter, Jr. (1970). "Lower bounds for relatively prime amicable numbers of opposite parity". Mathematics of Computation. 24 (112): 963–968. doi:10.2307/2004629. JSTOR 2004629. MR 0276167.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Erdős, Paul (2022). "On amicable numbers" (PDF). Publicationes Mathematicae Debrecen. 4 (1–2): 108–111. doi:10.5486/PMD.1955.4.1-2.16. S2CID 253787916. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ Gardner, Martin (1968). "Mathematical Games". Scientific American. 218 (3): 121–127. Bibcode:1968SciAm.218c.121G. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0368-121. ISSN 0036-8733. JSTOR 24926005. Archived from the original on 2022-09-25. Retrieved 2020-09-07.

- ^ Lee, Elvin (1969). "On Divisibility by Nine of the Sums of Even Amicable Pairs". Mathematics of Computation. 23 (107): 545–548. doi:10.2307/2004382. ISSN 0025-5718. JSTOR 2004382.

- ^ Patrick Costello, Ranthony A. C. Edmonds. "Gaussian Amicable Pairs." Missouri Journal of Mathematical Sciences, 30(2) 107-116 November 2018.

- ^ Clark, Ranthony (January 1, 2013). "Gaussian Amicable Pairs". Online Theses and Dissertations.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Amicable Pair". mathworld.wolfram.com.

- ^ Rocha, Rodrigo Caetano; Thatte, Bhalchandra (2015), Distributed cycle detection in large-scale sparse graphs, Simpósio Brasileiro de Pesquisa Operacional (SBPO), doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.1233.8640

References

edit- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Amicable Numbers". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Sándor, Jozsef; Crstici, Borislav (2004). Handbook of number theory II. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic. pp. 32–36. ISBN 978-1-4020-2546-4. Zbl 1079.11001.

- Wells, D. (1987). The Penguin Dictionary of Curious and Interesting Numbers. London: Penguin Group. pp. 145–147.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Amicable Pair". MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Thâbit ibn Kurrah Rule". MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Euler's Rule". MathWorld.

External links

edit- M. García; J.M. Pedersen; H.J.J. te Riele (2003-07-31). "Amicable pairs, a survey" (PDF). Report MAS-R0307.

- Grime, James. "220 and 284 (Amicable Numbers)". Numberphile. Brady Haran. Archived from the original on 2017-07-16. Retrieved 2013-04-02.

- Grime, James. "MegaFavNumbers - The Even Amicable Numbers Conjecture". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-11-23. Retrieved 2020-06-09.

- Koutsoukou-Argyraki, Angeliki (4 August 2020). "Amicable Numbers (Formal proof development in Isabelle/HOL, Archive of Formal Proofs)".

- Chernykh, Sergei. "Amicable pairs list". Retrieved 2023-09-10. (database of all known amicable numbers)