The Ohio Amish Country, also known simply as the Amish Country, is the second-largest community of Amish (a Pennsylvania Dutch group), with in 2023 an estimated 84,065 members according to the Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies at Elizabethtown College.[2]

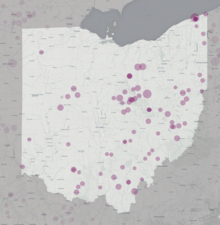

Amish settlements in Ohio. The largest centered around Holmes and Geauga Counties. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 84,065 (2023) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Holmes County settlement | 39,525 |

| Geauga County settlement | 20,440 |

| Religions | |

| Anabaptist Christianity (Old Order Amish • New Order Amish • Beachy Amish • Old Order Mennonites • Conservative Mennonites) | |

| Languages | |

| Pennsylvania Dutch, High German, English[1] | |

Ohio's largest Amish settlement is centered around Holmes County and in 2023 included an estimated 39,525 children and adults, the second largest in the world and the highest concentration of Amish in any US county; the Amish make up half the population of Holmes County, with members of other closely related Anabaptist Christian denominations, such as the Mennonites, residing there as well.[3] The second largest community in Ohio is centered around Geauga County.

Ohio's Amish Country in and around Holmes County is one of the state's primary tourist attractions and a major driver of the area's economy.

History

editThe Holmes County community was founded in 1808 and the Geauga County community in 1886.[4]: 139

At the time of the Holmes County settlement's founding there was at least one sizable village of Native Americans on the northern edge of what would become Holmes County, near the Killbuck river. Jacob Miller and his sons, Henry and Jacob, travelled in 1808 from Somerset County, Pennsylvania, and built a cabin northeast of the current village of Sugarcreek in Tuscarawas County. Henry overwintered on the claim, and the other two returned to Pennsylvania for the winter. The rest of the family, including Miller's nephew Jonas Stutzman, returned the next year in a Conestoga wagon pulled by a team of six, a trip that took a month.[5] The Millers settled in Tuscarawas, and Stutzman continued on to the area of the current village of Walnut Creek, about five miles west, and built a cabin on the creek.[5][6]: 27 [7] In 1810 six families and in 1811 two more families from Somerset County joined the Walnut Creek settlement. In 1818 the government decreased the land prices from $2 per acre to $1.25 and by 1835, the Holmes County settlement included two hundred and fifty families.[6]: 27 [5]

Beginning in the 1860s, a schism between conservative Amish, centered in Holmes County but occurring throughout North American Amish communities, separated the Amish into the Old Order Amish and the Amish Mennonites, most of whom merged into Mennonite communities.[4]: 42–43 [6]: 60 During the 1900s, the Holmes County community experienced multiple schisms into over thirty different groups, birthing several new orders and some that eventually became non-Amish.[4]: 146 The Schwartzentruber Amish, considered the most conservative of Amish orders, split off in the 1910s.[4]: 148 [6]: 37 The Andy Weaver order split off in the 1950s.[6]: 37 The New Order Amish, considered the most technologically liberal, split off in the 1960s.[4]: 148–149 [6]: 37

As of 2010 there were over fifty Amish settlements in Ohio[6]: 25 and 418 congregations, more than any other state.[8]: 8 Ohio's rural counties are attractive to Old Order Amish because travel by horse-drawn vehicle requires essential services such as shopping, banks and medical care to be within a distance manageable by that method of transportation, which limits travel to about 10 to 35 miles per day depending on various factors.[4]: 130 [9][1] Ohio State University researcher Joseph Donnermeyer called Ohio "the perfect mix", saying, "You can't be too rural. You have to be close enough to a town with the basic necessities."[9]

Population

editHolmes County has the highest concentration in the world, with the Amish in 2020 making up approximately half the population, and the largest population of Amish of all orders.[10][11] Including all communities, Ohio has the second-largest population of Old Order Amish in the world, with in 2023 an estimated 84,065 members, second to Pennsylvania with 88,850, according to the Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies at Elizabethtown College.[12]

Holmes County

editOhio's largest settlement is centered around Holmes County and in 2021 included an estimated 37,770 children and adults, the second largest in the world after the population of 41,000 centered around Lancaster County, Pennsylvania.[13] The Holmes County community includes multiple affiliations or orders[4]: 142 [14]: 6 and is the most highly-concentrated, diverse and complex of Amish settlements worldwide.[6] The settlement includes eleven separate Amish affiliations.[6]: 35 Four affiliations, the New Order Amish, Old Order Amish, Andy Weaver, and Swartzentruber, as of 2010 made up about 97% of church districts in the settlement, with the Old Order Amish the largest portion.[6]: 17–18 The Swartzentruber Amish include three separate groups, the Swartzentruber-Andy Weaver (which is unrelated to the Andy Weaver group), Swartzentruber-Mose Miller, and Swartzentruber-Joe Troyer, each of which considers itself the true Swartzentruber.[6]: 43 Other Amish groups include Stutzman-Troyer, Roman, Old Order Tobe, New Order Tobe, and New Order Christian Fellowship.[6]: 36 There are multiple other populations of Anabaptists in the area, including Beachy Amish, Brethren, and Mennonite.[6]: 32

The settlement stretches into the adjacent Ashland, Coshocton, Stark, Tuscarawas, and Wayne Counties.[9] Holmes County itself has the highest concentration of Amish in any US county;[9][15] the Amish make up half the county's population.[16] In contrast, in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, the Amish represent about 7% of the county's population.[13][17]

Holmes County has been projected to become the first in the US with a majority-Amish population.[18] Amish in general have high birth rates; as of 2012 in Holmes County, the most conservative groups had both the highest birth rates and the highest retention rates of young adults deciding to be baptized into the order.[4]: 162–163

Geauga County

editOhio's second largest settlement is centered around Geauga County with in 2021 an estimated 19,420 members, the fourth-largest in the world.[13]

Counties by percentage

editData from 2010 according to "Association of Religion Data Archives" (ARDA)[19] and from 2020 according to the "US Religion Census" report.[20][21] Data are only shown for Old Order Amish and exclude related groups such as Beachy Amish-Mennonite Churches, Maranatha Amish-Mennonite, Amish-Mennonites and Mennonites in general.

| County | Adherents (2010) |

Adherents (2020) |

Change 2010-20 |

% 2010 |

% 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Holmes | 17,654 | 19,793 | 12.1% | 41.67% | 44.76% |

| Geauga | 8,537 | 9,549 | 11.8% | 9.14% | 10.01% |

| Wayne | 9,283 | 9,130 | 1.6% | 8.10% | 7.81% |

| Coshocton | 1,760 | 2,533 | 43.9% | 4.77% | 6.92% |

| Knox | 2,111 | 2,843 | 34.7% | 3.46% | 4.53% |

| Ashtabula | 2,203 | 3,725 | 69.1% | 2.17% | 3.82% |

| Ashland | 1,661 | 1,877 | 13.0% | 3.13% | 3.58% |

| Monroe | 542 | 475 | 12.3% | 3.70% | 3.55% |

| Carroll | 614 | 937 | 52.6% | 2.13% | 3.51% |

| Hardin | 939 | 1,051 | 11.9% | 2.93% | 3.42% |

| Morrow | 590 | 1,175 | 99.2% | 1.69% | 3.36% |

| Tuscarawas | 2,370 | 3,128 | 32.0% | 2.56% | 3.35% |

| Noble | 0 | 434 | 0.00% | 3.07% | |

| Gallia | 733 | 875 | 19.4% | 2.37% | 3.00% |

| Harrison | 305 | 429 | 40.7% | 1.92% | 2.96% |

| Jackson | 339 | 875 | 158.1% | 1.02% | 2.68% |

| Trumbull | 3,864 | 5,044 | 30.5% | 1.84% | 2.50% |

| Guernsey | 552 | 806 | 46.0% | 1.38% | 2.10% |

| Adams | 471 | 501 | 6.4% | 1.65% | 1.82% |

| Logan | 640 | 738 | 15.3% | 1.39% | 1.60% |

| Vinton | 120 | 194 | 61.7% | 0.89% | 1.52% |

| Highland | 269 | 570 | 111.9% | 0.62% | 1.32% |

| Morgan | 95 | 91 | 4.2% | 0.63% | 0.66% |

| Meigs | 92 | 136 | 47.8% | 0.39% | 0.61% |

| Pike | 97 | 150 | 54.6% | 0.34% | 0.55% |

| Muskingum | 293 | 449 | 53.2% | 0.34% | 0.52% |

| Perry | 50 | 169 | 238.0% | 0.17% | 0.48% |

| Columbiana | 0 | 435 | 0.00% | 0.43% | |

| Portage | 387 | 619 | 59.9% | 0.24% | 0.38% |

| Mercer | 95 | 153 | 61.0% | 0.23% | 0.36% |

| Defiance | 124 | 137 | 10.5% | 0.32% | 0.36% |

| Medina | 616 | 571 | 7.3% | 0.36% | 0.31% |

| Richland | 313 | 343 | 9.6% | 0.25% | 0.27% |

| Van Wert | 0 | 70 | 0.00% | 0.24% | |

| Belmont | 95 | 122 | 28.4% | 0.13% | 0.18% |

| Huron | 103 | 108 | 4.9% | 0.17% | 0.18% |

| Pickaway | 53 | 97 | 83.0% | 0.09% | 0.17% |

| Stark | 447 | 602 | 34.7% | 0.12% | 0.16% |

| Williams | 63 | 61 | 3.2% | 0.16% | 0.16% |

| Marion | 60 | 96 | 60.0% | 0.09% | 0.15% |

| Preble | 0 | 62 | 0.00% | 0.15% | |

| Washington | 0 | 85 | 0.00% | 0.14% | |

| Athens | 0 | 80 | 0.00% | 0.13% | |

| Licking | 38 | 210 | 452.6% | 0.02% | 0.12% |

| Hocking | 17 | 25 | 47.0% | 0.06% | 0.09% |

| Scioto | 0 | 62 | 0.00% | 0.08% | |

| Fairfield | 127 | 110 | 13.3% | 0.09% | 0.07% |

| Ross | 103 | 31 | 69.9% | 0.13% | 0.04% |

| Total | 58,825 | 71,756 | 22.0% | 0.48% | 0.61% |

Congregations

editIn Ohio in 1998 the typical congregation consisted of 25 families and met every other week at a different family's home.[22] A meal is served following the service, which last approximately 4 hours.[7][23] Hymns are sung from the Ausbund, the oldest hymnal in continuous use.[7]

Economy

editA traditional source of income for most Ohio Amish is farming, and traditional farm life is central to the lives of most Amish.[1] In the southeastern areas of the Holmes County community, logging had been a traditional source of income.[24] As of 2010 approximately 17 percent of Amish heads of household in Holmes County and 7 percent in Geauga County reported their primary occupation as farming.[4]: 282 In 2003 a group of Holmes County Amish leaders established Green Field Farms, a cooperative wholesaler of organic agricultural products whose membership is limited to those who use horse-drawn vehicles.[4]: 286

From the early 2010s, sheep farming has become increasingly common as the land in much of the Holmes County area is better for foraging than for farming, and sheep are good foragers that do not need as much expensive feed as cows.[24] Sheep can also be more profitable on smaller acreage than larger livestock.[24] As early as the 1990s Amish farmers adopted organic farming methods; there were no certified organic dairies in Ohio in 1997, but within a few years there were more than one hundred, 90% of which were either Old Order Mennonite- or Amish-owned.[4]: 286

Many Amish supplement farming income with sales of hand-made goods such as brooms, baskets, quilts, leather goods, woodworking, and other artisan products sold from homes or in local shops.[1][25] Some own or work in area businesses surrounding the use of wood, such as carpentry, woodworking, furniture production, pallet production, or lumber wholesale or retail businesses.[15][26][27] As of 2010 three of the largest non-Amish employers of Amish were garage-door manufacturer Wayne-Dalton, Keim Lumber, and Weaver Leather.[6]: 10

On April 1, 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic protective gear shortages, members of the Holmes County settlement were asked by the Cleveland Clinic to sew masks for its employees and visitors.[28] Local businessmen John Miller and Abe Troyer organized a sewing "frolic", a term used by the Amish to mean put together a group effort.[28] Many Amish seamstresses had been idled by the pandemic's shutdowns, and Amish do not apply for social benefits, so the work helped sustain their families.[28]

Other local businesses pivoted to creating face shields, dividers for field hospitals, fluid-resistant gowns, shoe coverings, and other items.[28] By April 9 the Cleveland Clinic was receiving 10,000 masks a day and one local business was producing 100,000 face shields per day.[28]

Tourism

editEfforts to promote the Holmes County community as a tourist destination began in the 1950s.[29]: 26 Approximately four million tourists visit Holmes County each year as of 2012; the direct economic impact at the time was estimated at $154 million annually.[29]: 26 Amish tourism is a major part of the economy of Holmes County.[4]: 392 [6]: 30, 177

Interest in the Amish was increased by the 1955 Broadway musical Plain and Fancy.[4]: 53 By the 1960s bus tours of Holmes County were available.[4]: 53 The towns of Millersburg (the county seat), Berlin, Walnut Creek, and Charm in Holmes County, and Sugarcreek just across the county line in Tuscarawas County, have a large tourism industry.[30] In 2017, Holmes County was the second most popular tourist destination in Ohio.[31]

Tourism centers

editOhio's Amish tourism centers around the towns of Berlin and Walnut Creek in Holmes County, and in Sugarcreek, just across the border in Tuscarawas County, all of which are situated along US Route 30.[29]: 43–44

Beginning in the 1990s business leaders have developed Walnut Creek into an American-Victorian themed town, which the University of Dayton's Susan Trollinger calls "puzzling" because of the stark contrast between Victorian overdecorating and the Amish plainness.[29]: 49–50 Tourist-oriented businesses typically include "resting places" such as parlors in hotels or wrapround porches lined with rocking chairs or other seating on retail shops, which emphasizes a sense of having plentiful time.[29]: 57 Her conclusion is that the Victorian theme and emphasis on resting places is capitalizing on the attraction of nostalgia for a simpler life with plentiful time, which it has in common with the Amish.[29]: 51–60 Large parking lots and sidewalks connect the business district, which is condensed into six square blocks and connected by wide sidewalks, further encouraging a feeling of a slower-pace and life lived on foot.[29]: 59 American flags and other patriotic-themed decor are commonly displayed in both exterior and interior spaces, which Trollinger again finds interesting when contrasted to the Amish, who refuse to recite the Pledge of Allegiance and do not fly flags at their schools and homes.[29]: 70

More tourists visit Berlin, permanent population 685, than any other town in Ohio Amish Country.[29]: 83 Berlin was the first town in Ohio to market the Amish to tourists.[29]: 83 Berlin's business district is large, with as of 2012 more than 40 shops, 10 hotels, and multiple restaurants large and small.[29]: 85 Trollinger calls its architecture and offerings "eclectic" but dominated by the American frontier and the 1950s and points out that like Walnut Creek, all call back to the past.[29]: 88, 106 Trollinger argues that the frontier theme in Berlin presents a story of peaceful people leaving crowded cities behind in order to make a better life for themselves and their families.[29]: 94

Sugarcreek's historical beginnings were rooted in cheese production. Swiss immigrants arrived in the early 1830s and used the milk from Amish dairy farms to produce their cheese and in the 1950s created an annual Ohio Swiss Festival; the success of early festivals as an attraction for tourists resulted in local business leaders transforming the town into a Swiss village starting in 1965.[29]: 117–119 By the early 70s the first tourist-oriented businesses were opening, and the tourism industry in Sugarcreek was centered not only around the Amish but also around a steam engine passenger train operated by the Ohio Central Railroad which ran between Sugarcreek and Baltic until 2004. Since the train stopped running, tourism in Sugarcreek has decreased.[29]: 118–120 Trollinger theorizes that unlike Walnut Creek and Berlin, which support a nostalgia that reassures tourists that what they are nostalgic for still exists in America, and is therefore a nostalgia of hope, the Swiss theme of Sugarcreek inspires a nostalgia for something that is forever gone—that is, a period in which the United States was a white-majority country—and so does not reassure.[29]: 134–135, 142

Tourists and the tourist experience

editAccording to Trollinger the Amish tourist experience is targeted very strategically to attract a specific audience.[29]: 141 She describes typical Amish Country tourists as a "relatively homogeneous group": white, working or middle-class, middle-aged to retirement-aged Americans visiting with their spouse and another married couple who arrive in late-model American-made SUVs or minivans and often wearing shirts with American flags, sports team logos, or Harley Davidson logos.[29]: 28–29 Trollinger concludes that the average tourist is of "moderate income, average education, and moderately conservative views."[29]: 28–29

Trollinger theorizes that Amish Country tourism reassures visitors that a form of traditional American life still exists even during and after periods of rapid societal change.[29]: xxi, 33–43, 50–55 She notes that the largest of the tourist-oriented restaurants serves scratch-cooked meals "family style", serving all food in common serving dishes from which each person serves themself, serving dishes are refilled until all are satisfied, and nothing on the table is a convenience item, which she says "recreat(es) a cultural memory of family" and the sharing of a homecooked meal.[29]: 54–57 The most visible Amish in Amish country are typically young women making, serving, or selling food; shopping with multiple young children in tow; or men doing woodwork or farming or driving buggies.[29]: 79, 105 Taken all together, Trollinger argues, the tourism experience in Amish Country, and especially in Walnut Creek and Berlin, reassures the tourist that "it is still possible to live at a leisurely pace, to have clarity about what it means to be a man or a woman, to feel patriotic".[29]: 79

According to Trollinger, some Amish view tourists as an opportunity to "shar(e) their Christian witness through their visibly different common life and daily practices."[29]: xiv Some "expressed compassion" for the tourists, whose daily lives were filled with pressure and who were charmed by the slower paced and simpler life of the Amish.[29]: xiv

Amish Country Byway

editThe Amish Country Byway is an Ohio Scenic Byway, designated in 1998, that runs 164 miles (264 km) through many Amish communities in Holmes County.[32] The byway focuses on backroads with views of rolling farmland and concentrations of Amish homes, farms, and home businesses.[33]

Amish & Mennonite Heritage Center

editThe Amish & Mennonite Heritage Center is a museum in eastern Holmes County, in Berlin, Ohio.[34] It opened in 1981 as the Mennonite Information Center. By 1989 it had moved to the current structure which was finished to include the Behalt Cyclorama as well as a bookstore. The center was renamed in 2002 to reflect its mission as a cultural center.[35][36][37]

Behalt

editBehalt, meaning "to keep or to remember", is a 10 ft × 265 ft (3.0 m × 80.8 m) cyclorama by Heinz Gaugel located in the museum.[38][39][34] According to the Columbus Dispatch it has been called the “Sistine Chapel of the Amish and Mennonites”.[38] Anabaptist scholar Susan Biesecker-Mast calls it "an effort to exceed the tourist economy of Holmes County by offering a transformative rhetoric for its visitors".[40] The painting was created over 14 years and completed in 1992.[41][42] It is one of four existing cycloramas in the US and one of only 16 in the world; Behalt is the only existing cyclorama painted by a single artist.[41][34] It follows the development of Anabaptism from the time of Jesus through the 1990s and portrays approximately 1200 biblical and historical figures.[43][41]

Medical care

editThe Amish do not reject medical care, but an increasing number reject vaccination; in the early 2010s, 14% of the Amish in Ohio reported their children were unvaccinated, while in 2021 59% reported not vaccinating children.[44] In 2014 Holmes and Knox Counties experienced a measles outbreak after men from the community returned from a mission trip building houses in the Philippines.[45][46][47]

Holmes County has the lowest COVID-19 vaccination rates in the state, and fewer than 1% of Amish had been vaccinated by April 2021.[16] When vaccines became available for COVID-19, the county posted the lowest vaccination rates of Ohio's 88 counties and among the lowest in the country.[48] As of February 13, 2022, fewer than 20% of county residents had been vaccinated as compared to approximately 60% statewide.[49]

Holmes County is the least-insured county in Ohio, as the Amish typically do not use commercial health insurance but instead contribute to a community fund.[18]

Politics

editThe Amish tend to be conservative and to vote that way.[15] Voting outcomes in Holmes County on issues that are important to the Amish, such as those concerning the schools and alcohol sales, tend to be affected by the Amish vote.[15] In some Holmes County townships all businesses except gas stations are closed on Sundays (cf. Sunday Sabbatarianism).[15] Many of Holmes County's townships are dry.[citation needed]

Housing

editThe Amish in Ohio typically build spacious two-story houses. Styles include the I-house, which is side-gabled and typically a single room deep, typically symmetrical on all sides, and includes full-length porches on the front and back sides.[29]: 50 Sometimes the I-house will add a wing in the back.[29]: 50 A second form is a one-and-a-half or two story gable front house. Roof pitches are moderate and houses are typically wood-clad and painted white.[29]: 50

Schools

editIn 1914 the first clash over state-regulated mandatory school attendance until 16 occurred in Geauga County when three Amish fathers received fines when they did not send their children to school for 9th grade.[4]: 251–252 In the 1920s and 1930s there were similar clashes in other states, resulting in a rise in Amish parochial schools and a case before the Supreme Court which found that mandatory school attendance until 16 interfered with free exercise of religion among the Amish.[4]: 254–255 Many Amish schools are former one-room public schoolhouses that the local Amish church districts purchased when public schools consolidated into multi-classroom campuses.[50]: 109, 207

As of 2010 the Flat Ridge Elementary School, a public school in the East Holmes Local Schools district, had a student body that was 100% Amish.[6]: 8 Holmes County as of 2009 had over 200 Amish parochial schools; approximately half the Amish students in the county were enrolled in public schools.[6]: 142, 153 The Amish celebrate January 6, or Epiphany, as "Old Christmas"; the public schools remain open but Amish students are excused, which means some classrooms, or in the case of Flat Ridge Elementary entire schools, are empty.[51]

Curriculum

editAmish schools are regulated by the Minimum Standards for the Amish Private Elementary Schools of the State of Ohio (Ohio Minimum Standards), which requires certain subjects be taught, including English, mathematics, geography, history, health, German, vocal music. Classes are required to be taught in English, still the second language for most Amish, except in German classes.[50]: 111, 146 In practice, each school sets its own curriculum, and according to Karen Johnson-Weiner, despite the Ohio Minimum Standards, certain subjects—typically geography, history, and health—are sometimes not taught because of objections from teachers or parents.[50]: 111–113 Some Old Order Amish parents object to teaching history because "there is too much glorification of war". Johnson-Weiner reported in 2007 that students at a school taught by a Swartzentruber member didn't study geography or health because of the teacher's objection to teaching those subjects.[50]: 112

Textbooks

editTexts are typically chosen from those offered by several publishers, including Pathway Publishing Company, Gordonville Printing Company, and Study Time, which are Old Order Amish presses, or the Schoolaid Publishing Company or Rod and Staff, which are Mennonite presses.[50]: 112

Some, such as Gordonville, reprint texts such as Essentials of English Spelling, first published in 1919, for very conservative schools. Some supply reprints of early editions of McGuffey Readers to Swartzentruber schools.[50]: 208–209 The Dick and Jane series from the 1950s are valued by some schools for presenting a non-Amish world but one that "does not expose (students) to the dangers of modern society".[50]: 209–210 The Strayer-Upton Practical Arithmetics Series, first published in the 1920s, similarly uses story problems that do not represent modern life.[50]: 58, 210 The texts are also valued for their emphasis on rote learning, mastery of basics, and respect for authority and for relative lack of emphasis on discussion-based learning.[50]: 210–211 Many conservative Old Order Amish also avoid carrying religion into the schools, as they believe parents and religious leaders, rather than schoolteachers, should be teaching religion; these older texts tend to be "moralistic...but religiously neutral".[50]: 211 The older texts are also valued for the continuity they provide; children are learning from the same textbooks as their parents and grandparents.[50]: 211

Other publishers, such as Pathway, created texts specifically designed for use in Old Order Amish schools using a combination of curated stories and essays originally published elsewhere and those written for the purpose. The eight-grade Pathway Reader, Our Heritage, contains poetry by Longfellow and Whitman as well as the stories of Dirk Willems and the Hochstetler Massacre.[50]: 216+ Illustrations in the series contain no images of people. Some conservative communities have rejected the Pathway Readers as too progressive in its approach and too implicitly religious, .[50]: 218 Pathway Readers, the first of which were published in 1968, as of 2007 had not been revised.[50]: 219

School Aid and Study Time also publish purpose-created textbooks along with teaching materials, and periodically updates texts with input from teachers and new pedagogy.[50]: 219–223

Some teachers, especially in Swartzentruber schools, create their own teaching materials, making multiple copies for student use with homemade hectographs.[50]: 252

Teachers

editAccording to Johnson-Weiner writing in 2007, teachers are typically not chosen from a pool of applicants but instead recruited by school board members.[50]: 126 Ohio Minimum Standards does not require teachers to have more than an eighth-grade education but does encourage "a self-imposed research into the school's accepted subjects".[50]: 127

Media

editThe Budget, a weekly Amish and Mennonite correspondence newspaper distributed in various Amish communities throughout the US and in other countries, is produced in Sugarcreek, which is part of the Holmes County settlement.[28] Issues contain letters from "scribes", usually women, reporting what has been happening in their church district.[6]: 102 [10]: 188 The paper is published in English; while the first language most Old Order Amish learn is Pennsylvania Dutch, a dialect of German, many older Amish did not learn to read or write it.[52][23] William Schreiber notes the tendency for German phrasing and the occasional German word in many contributions.[52]

The Budget started in 1890 as a local newspaper for the town of Sugarcreek.[10]: 189–190 The first 14-page issue was published May 15, 1890, by John C. Miller, known as "Budget John".[52] By the 1920s most of the letter correspondents were Mennonite, but by the late 1930s were mostly Old Order Amish.[10]: 189–190 By 1959 the paper was delivered to 42 states and 10 foreign countries.[52]

As of 2008 the paper published approximately 300 letters each week and had a subscription of 10,000.[10]: 182 As of 2010 an edition ran to 50 pages, primarily containing letters from Amish communities throughout the world, and sold for $1.[1] Scribes are unpaid but receive envelopes and stamps;[10]: 185 handwritten letters arrive to the office of the newspaper via mail and fax.[53] Steven Nolt called The Budget, along with another Amish correspondence newspaper Die Botschaft, important vehicles for creating a sense of community.[10]: 183–185

The Gemeinde Register is a biweekly newsletter published in Baltic, Ohio, that serves the Ohio Amish community.[4]: 156 [54]

Carlisle Printing near Walnut Creek publishes the Ohio Amish Directory once every five years; as of 2010 it had grown to 900 pages and includes births, deaths, marriages, and occupations for all Amish except the Swartzentrubers.[6]: 9

Amish Helping Fund

editIn 1995 several Old Order Amish leaders created a nonprofit to assist young couples in purchasing their first home. As of 2010 the fund held $80 million and had never had a foreclosure; loans are restricted to purchasing property for earning a livelihood and not for hunting.[6]: 103

See also

edit- Bergholz Community, an offshoot of the Holmes County Amish community

References

edit- ^ a b c d e Winnerman, Jim (September 12, 2010). "Trip back in time: the Amish in Ohio". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Archived from the original on July 1, 2016. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ "Amish Population Profile, 2023". Elizabethtown College, the Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies. September 2, 2023. Archived from the original on September 2, 2023. Retrieved September 3, 2023.

- ^ "The Amish and Their Mennonite Neighbors". Best of Ohio's Amish Country. June 28, 2019. Archived from the original on April 8, 2023. Retrieved April 8, 2023.

While there are a few small groups of Mennonites that do not own automobiles, there are none in the Holmes County community that do not permit ownership of the automobile. In the Greater Holmes County Amish Community, automobile ownership is one of the ways one can define whether they are Amish or Mennonite.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Kraybill, Donald B. (2013). The Amish. Karen Johnson-Weiner, Steven M. Nolt. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-0914-6. OCLC 810329297. Archived from the original on May 18, 2024. Retrieved September 4, 2021.

- ^ a b c Miller, Betty Ann (1977). Amish Pioneers of the Walnut Creek Valley. Atkinson Printing. ISBN 978-0-685-87375-5. Archived from the original on May 18, 2024. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Hurst, Charles E. (2010). An Amish paradox : diversity & change in the world's largest Amish community. David L. McConnell. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-9790-0. OCLC 647908343. Archived from the original on May 18, 2024. Retrieved September 4, 2021.

- ^ a b c Vonada, Damaine (August 1998). "Welcome to Ohio's Amish Country". Ohio. pp. 70–79.

- ^ Kraybill, Donald B. (2010). Concise encyclopedia of Amish, Brethren, Hutterites, and Mennonites. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-9657-6. OCLC 461896783.

- ^ a b c d Blackwell, Brandon (August 6, 2012). "Amish settlements in Ohio, North America on the rise". The Plain Dealer. Archived from the original on March 1, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Umble, Diane Zimmerman; Weaver-Zercher, David, eds. (2008). The Amish and the media. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8789-5. OCLC 167496604. OL 16672558M.

- ^ Clark, Jayne (July 2, 1995). "Bargains and Old-fashioned Charm". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- ^ "Amish Population 2021". Elizabethtown College. August 14, 2020. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Twelve Largest Settlements, 2021". Elizabethtown College. August 10, 2021. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ Lumry, Amanda (2002). Holmespun : an intimate portrait of an Amish and Mennonite community. Loren Wengerd, Laura Hurwitz (1st ed.). Bellevue, WA: Eaglemont Press. ISBN 0-9662257-6-7. OCLC 52460591.

- ^ a b c d e Fiala, Donna (August 20, 2015). "Around Town: Truly conservative: Living life the Amish way in Holmes County, Ohio". Naples News. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ a b Huntsman, Anna (April 28, 2021). "COVID-19 Has Hit The Amish Community Hard. Still, Vaccines Are A Tough Sell". NPR. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ The 12 Largest Amish Communities (2017). Archived January 1, 2018, at the Wayback Machine at Amish America

- ^ a b Pfleger, Paige (August 27, 2019). "Amish Paradise: Living Uninsured But Healthy In Rural Ohio". WOSU-TV. Archived from the original on April 23, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ "Association of Religion Data Archives". Archived from the original on August 3, 2023. Retrieved August 11, 2023.

- ^ "2020 Study Information". Archived from the original on October 3, 2023. Retrieved August 11, 2023.

- ^ "U.S. Religion Census | Maps and data files for 2020". Archived from the original on July 27, 2023. Retrieved August 11, 2023.

- ^ Rovito, Markkus (April 1997). "Religion Dictates Amish Life". Ohio. p. 98.

- ^ a b Williams, Deborah (July 12, 1998). "Living off the land, the Amish way". The Buffalo News. pp. G1, G4.

- ^ a b c Reese, Matt. "Sheep offering options for Ohio's Amish". Ohio Ag Net | Ohio's Country Journal. Archived from the original on August 18, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ Larsen, Doris (December 16, 2004). "Winter in Amish Country". Cleveland Magazine. Archived from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ Diebel, Matthew (August 15, 2014). "The Amish: 10 things you might not know". USA Today. Archived from the original on August 16, 2014. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ Eshelby, Kate (March 10, 2019). "Turning back time with the Amish of Ohio". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 10, 2019. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Williamson, Elizabeth (April 9, 2020). "In Ohio, the Amish Take On the Coronavirus". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 23, 2020. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Trollinger, Susan L. (2012). Selling the Amish : the tourism of nostalgia. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-0467-7. OCLC 823654526.

- ^ Walle, Randi (May 31, 2018). "Explore Ohio Amish Country". Columbus Underground. Archived from the original on September 23, 2020. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ Lynch, Kevin (November 27, 2017). "Holmes County tourism, hotels keep growing". The Daily Record. Archived from the original on August 18, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ "2020 Amish Country Byway Corridor Management Plan (CMP)" (PDF). Ohio Department of Transportation. June 2019. Retrieved August 31, 2021.

- ^ Warren, Rich (May 2010). "Into Amish Country". Home & Away. pp. 42–44.

- ^ a b c Brownlee, Amy Knueven (July 1, 2011). "The Simple Life". Cincinnati Magazine. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ "About Us | Amish & Mennonite Heritage Center". Behalt.com. Archived from the original on August 6, 2017. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- ^ Alice T. Carter (August 3, 2013). "Road Trip: Ohio's Amish Country". TribLIVE. Archived from the original on December 23, 2016. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- ^ Miller, Nancy Baren (July 1997). "Amish Buggies in Little Switzerland". Family Motor Coaching. pp. 94+.

- ^ a b Brown, Gary (October 18, 2013). "Postcard from ... Berlin: Behalt Cyclorama tells the story of the Anabaptists". The Columbus Dispatch. Archived from the original on August 19, 2021. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ "Behalt Cyclorama". Amish & Mennonite Heritage Center. Archived from the original on February 1, 2020. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Biesecker-Mast, Susan (July 1, 1999). "Behalt: a rhetoric of remembrance and transformation". Mennonite Quarterly Review. 73 (3): 601–615. Archived from the original on May 18, 2024. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ a b c Lueptow, Diana (April 25, 2019). "Memory Center". Akron Life Magazine. Archived from the original on May 18, 2024. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Minnich, Kate (April 1, 2016). "Behalt". The Daily Record. Archived from the original on August 19, 2021. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Glaser, Susan (December 25, 2011). "Explore the vast variety of Ohio's religious cultures". The Plain Dealer. Archived from the original on August 19, 2021. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Scott, Ethan M.; Stein, Rachel; Brown, Miraides F.; Hershberger, Jennifer; Scott, Elizabeth M.; Wenger, Olivia K. (February 12, 2021). "Vaccination patterns of the northeast Ohio Amish revisited". Vaccine. 39 (7): 1058–1063. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.01.022. PMID 33478791. S2CID 231678869. Archived from the original on May 18, 2024. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ Schladen, Marty (March 21, 2020). "In Ohio's Amish Country, coronavirus is taken seriously, health officials say". Akron Beacon Journal. Archived from the original on March 22, 2020. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ Gastañaduy, Paul A.; Budd, Jeremy; Fisher, Nicholas; Redd, Susan B.; Fletcher, Jackie; Miller, Julie; McFadden, Dwight J.; Rota, Jennifer; Rota, Paul A.; Hickman, Carole; Fowler, Brian (October 6, 2016). "A Measles Outbreak in an Underimmunized Amish Community in Ohio". New England Journal of Medicine. 375 (14): 1343–1354. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1602295. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 27705270.

- ^ Tribble, Sarah Jane (June 25, 2014). "Ohio Amish begin vaccinations amid largest measles outbreak in recent U.S. history". PBS NewsHour. Archived from the original on October 19, 2019. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ Stratford, Suzanne (July 29, 2021). "'Not surprised': Holmes County reporting lowest COVID-19 vaccination numbers in Ohio". WJW-TV. Archived from the original on July 29, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ "Overview". coronavirus.ohio.gov. February 14, 2022. Archived from the original on February 12, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Johnson-Weiner, Karen (2007). Train up a child : Old Order Amish & Mennonite schools. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4356-9211-4. OCLC 310123226. Archived from the original on May 18, 2024. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ Lynch, Kevin (January 4, 2022). "Old Christmas is a time for reflecting, visiting family among Ohio's Amish". The Daily Record. Archived from the original on January 31, 2022. Retrieved January 31, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Schreiber, William I (1962). Our Amish neighbors. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 145–146. OCLC 603972387. Archived from the original on May 18, 2024. Retrieved March 12, 2023.

- ^ Giffels, David (May 23, 1999). "All the Amish news that's fit to print". Akron Beacon Journal. pp. 4–6.

- ^ Hurst, Charles E.; McConnell, David L. (April 5, 2010). An Amish Paradox: Diversity and Change in the World's Largest Amish Community. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-9790-0. Archived from the original on May 18, 2024. Retrieved February 4, 2022.