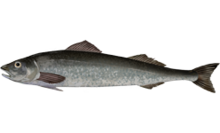

The sablefish (Anoplopoma fimbria) is one of two members of the fish family Anoplopomatidae and the only species in the genus Anoplopoma.[1] In English, common names for it include sable (US), butterfish (US), black cod (US, UK, Canada), blue cod (UK), bluefish (UK), candlefish (UK), coal cod (UK), snowfish (ปลาหิมะ; Thailand), coalfish (Canada), beshow, and skil (Canada), although many of these names also refer to other, unrelated, species.[2] The US Food and Drug Administration accepts only "sablefish" as the acceptable market name in the United States; "black cod" is considered a vernacular (regional) name and should not be used as a statement of identity for this species.[3] The sablefish is found in muddy sea beds in the North Pacific Ocean at depths of 300 to 2,700 m (980 to 8,860 ft) and is commercially important to Japan.[4][5]

| Sablefish | |

|---|---|

| |

| Anoplopoma fimbria | |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Perciformes |

| Family: | Anoplopomatidae |

| Genus: | Anoplopoma Ayres, 1859 |

| Species: | A. fimbria

|

| Binomial name | |

| Anoplopoma fimbria (Pallas, 1814)

| |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Description

editThe sablefish is a species of deep-sea fish common to the North Pacific Ocean.[6] Adult sablefish are opportunistic piscivores, preying on Alaskan pollock, eulachon, capelin, herring, sandlance, and Pacific cod, as well as squid, euphausiids, and jellyfish.[7] Sablefish are long-lived, with a maximum recorded age of 94 years[8] although the majority of the commercial catch in many areas is less than 20 years old.[9][10]

Sablefish growth varies regionally, with larger maximum sizes in Alaska,[10] where total lengths up to 114 cm (45 in) weights up to 25 kg (55 lb) have been recorded.[11] However, average lengths are typically below 70 cm (28 in) and 4 kg (8.8 lb).[11][10]

Tagging studies have indicated that sablefish have been observed to move as much as 2,000 km (1,200 mi) before recapture with one study estimating an average distance between release and recapture of 602 km (374 mi), with an average annual movement of 191 km (119 mi).[12][13]

-

Sablefish resting on soft sediment 991 feet deep

-

Small sablefish caught in a bottom trawl survey off the coast of California

-

A tote of sablefish being processed in Juneau, Alaska.

Fisheries

editSablefish are typically caught in bottom trawl, longline and pot fisheries. In the Northeast Pacific, sablefish fisheries are managed separately in three areas: Alaska, the Canadian province of British Columbia, and the west coast of the contiguous United States (Washington, Oregon, and California). In all these areas catches peaked in the 1970s and 80s and have been lower since that time due to a combination of reduced populations and management restrictions.[9][14][10] The sablefish longline fishery in Alaska has been certified as sustainable by the Marine Stewardship Council[15] as is the US West Coast limited entry groundfish trawl fishery which includes sablefish.[16]

Longline fisheries in Alaska frequently experience predation of sablefish by killer whales and sperm whales which remove the fish from the hooks during the process of retrieving the gear.[17][18][19]

Sablefish aquaculture is an area of active research.[20]

Culinary use

editThe white flesh of the sablefish is soft-textured and mildly flavored. It is considered a delicacy in many countries.[which?] When cooked, its flaky texture is similar to Patagonian toothfish (Chilean sea bass). The meat has a high fat content and can be prepared in many ways, including grilling, smoking, or frying, or served as sushi.[21] Sablefish flesh is high in long-chain omega-3 fatty acids, EPA, and DHA. It contains about as much as wild salmon.[22]

Smoked sablefish, often called simply "sable", has long been a staple of New York appetizing stores, one of many smoked fish products usually eaten with bagels for breakfast in American Jewish cuisine.[23][24]

In Japanese cuisine, the black cod (gindara) is often cooked saikyo yaki style, marinated for several days in sweet white miso or sake lees (kasuzuke) then broiled.[25] The Japanese-Peruvian-American chef Nobu Matsuhisa introduced his version of gindara saikyo yaki at his restaurant in Los Angeles, and brought it to his New York restaurant Nobu in 1994, where it is considered his signature dish, under the name "Black Cod with Miso".[26][27][23] Kasuzuke sablefish is popular in Seattle thanks to a large Japanese community in that area.[28]

Nutrition

editNutritional information for sablefish is as follows.[29]

|

|

Mercury content

editStudies of accumulated mercury levels find average mercury concentrations from 0.1 ppm,[30]: 15 0.2 ppm,[31] and up to 0.4 ppm.[32] The US Food and Drug Administration puts sablefish in the "Good Choices" category in their guide for pregnant women and parents, and recommends one 4-ounce serving (uncooked) a week for an adult, less for children.[33][34] On the other hand, the Alaska epidemiology section considers Alaska sablefish to be "low in mercury"[30]: 7 and advises no restrictions on sablefish consumption by all populations.[30]: 50

References

edit- ^ a b Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Anoplopoma fimbrata". FishBase. August 2022 version.

- ^ "Common Names List - Anoplopoma fimbria". Fishbase.org. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- ^ "Seafood List Search Returns". Archived from the original on 17 July 2010. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ^ Sonu, Sunee C. (October 2014). "Supply and Market for Sablefish in Japan" (PDF). NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS. NOAA-TM-NMFS-WCR-102.

- ^ Burros, Marian (16 May 2001). "The Fish That Swam Uptown". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ^ "Anoplopoma fimbria". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 24 January 2006.

- ^ Yang, M-S and M. W. Nelson 2000. Food habits of the commercially important groundfishes in the Gulf of Alaska in 1990, 1993, and 1996. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-AFSC-112. 174 p.

- ^ Kimura, Daniel K., A. M. Shaw and F. R. Shaw 1998. Stock Structure and movement of tagged sablefish, Anoplopoma fimbria, in offshore northeast Pacific waters and the effects of El Nino-Southern Oscillation on migration and growth. Fish. Bull. 96:462-481.

- ^ a b Hanselman DH, Rodgveller CJ, Lunsford CR, Fenske, KH (2017), Assessment of the Sablefish stock in Alaska in: Stock assessment and fishery evaluation report for the groundfish resources of the GOA and BS/AI (PDF), North Pacific Fishery Management Council, 605 W 4th Ave., Suite 306 Anchorage, AK 99501, USA, pp. 307–412

- ^ a b c d Haltuch MA, Johnson KF, Tolimieri N, Kapur MS, Castillo-Jordán CA (2019), Status of the sablefish stock in U.S. waters in 2019, Pacific Fisheries Management Council, 7700 Ambassador Place NE, Suite 200, Portland, OR, U.S.A.

- ^ a b "Sablefish Species Profile, Alaska Department of Fish and Game". www.adfg.alaska.gov. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ Beamish, R. J.; McFarlane, C. A. (1988). "Resident and Dispersal Behavior of Adult Sablefish (Anaplopoma fimbria) in the Slope Waters off Canada's West Coast". Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 45 (1): 152–164. doi:10.1139/f88-017. ISSN 0706-652X.

- ^ Hanselman, Dana H.; Heifetz, Jonathan; Echave, Katy B.; Dressel, Sherri C. (2015). "Move it or lose it: movement and mortality of sablefish tagged in Alaska". Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 72 (2): 238–251. doi:10.1139/cjfas-2014-0251. ISSN 0706-652X.

- ^ DFO (2016), A revised operating model for sablefish (Anoplopoma fimbria) in British Columbia, Canada (PDF), DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Sci. Advis. Rep. 2016/015

- ^ "US North Pacific sablefish - MSC Fisheries". fisheries.msc.org. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ "US West Coast limited entry groundfish trawl - MSC Fisheries".

- ^ Peterson, Megan J.; Carothers, Courtney (1 November 2013). "Whale interactions with Alaskan sablefish and Pacific halibut fisheries: Surveying fishermen perception, changing fishing practices and mitigation". Marine Policy. 42: 315–324. Bibcode:2013MarPo..42..315P. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2013.04.001. ISSN 0308-597X.

- ^ Sigler, Michael F.; Lunsford, Chris R.; Straley, Janice M.; Liddle, Joseph B. (2008). "Sperm whale depredation of sablefish longline gear in the northeast Pacific Ocean". Marine Mammal Science. 24 (1): 16–27. Bibcode:2008MMamS..24...16S. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2007.00149.x. ISSN 0824-0469.

- ^ Sperm whales steal from a fishing boat - Alaska: Earth's Frozen Kingdom - Episode 1 - BBC Two, 3 February 2015, archived from the original on 21 December 2021, retrieved 24 August 2018

- ^ "Jamestown S'Klallam, NOAA Partner on Black Cod Broodstock Program". Northwest Treaty Tribes. 27 March 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ "18 Best Sablefish Recipes To Try". Glorious Recipes. 19 June 2023. Retrieved 3 October 2023.

- ^ "Sablefish Anoplopoma fimbria". FishWatch. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ a b Marian Burros, "The Fish that Swam Uptown", New York Times, May 16, 2001, page F1

- ^ Leah Koenig, "A Smoked Fish Primer", The Forward July 1, 2016

- ^ "Miso-marinated broiled fish", recipe in Elizabeth Andoh, Washoku: Recipes from the Japanese Home Kitchen, 2012, ISBN 030781355X, p. 229

- ^ Nobu Matsuhisa, Nobu: A Memoir, 2019, ISBN 1501122800, p. 47

- ^ Ruth Reichl, "Restaurants", New York Times, October 7, 1994, p. C24

- ^ Loomis, Susan Herrmann (26 June 1988). "Seattle's Sake-Marinated Fish". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ^ Exact Scientific Services. (2023). West Coast Groundfish Nutrient Profiles: Exact Scientific Lab Results. Commissioned by Jana Hennig. Retrieved from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5a3051588fd4d2db4fb25f26/t/63e40842950bac0c12f8e22b/1675888709465/0+West+Coast+Groundfish+nutrient+profiles+-+Exact+Scientific+lab+results.pdf

- ^ a b c Ali K. Hamade; Alaska Scientific Advisory Committee for Fish Consumption (21 July 2014). "Fish Consumption Advice for Alaskans: A Risk Management Strategy To Optimize the Public's Health" (PDF). Section of Epidemiology, Division of Public Health, Department of Health and Social Services, State of Alaska. Retrieved 9 September 2023.

- ^ "Human Health Risk Assessment of Mercury in Fish and Health Benefits of Fish Consumption". 9 March 2007.

- ^ "Mercury Levels in Commercial Fish and Shellfish (1990–2012)". FDA. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ U.S. Food & Drug Administration, "Eating Fish: What Pregnant Women and Parents Should Know" [1]

- ^ U.S. Food & Drug Administration, "Questions & Answers from the FDA/EPA Advice on What Pregnant Women and Parents Should Know about Eating Fish" [2]