Union busting is a range of activities undertaken to disrupt or weaken the power of trade unions or their attempts to grow their membership in a workplace.

Union busting tactics can refer to both legal and illegal activities, and can range anywhere from subtle to violent. Labor laws differ greatly from country to country in both level and type of regulations in respect to their protection of unions, their organizing activities, as well as other aspects. These laws can affect topics such as posting notices, organizing on or off employer property, solicitations, card signing, union dues, picketing, work stoppages, striking and strikebreaking, lockouts, termination of employment, permanent replacements, automatic recognition, derecognition, ballot elections, and employer-controlled trade unions.[1]

Article 23 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights declares that everyone has a right to form or join a trade union.[2] The provision is, however, not legally binding and has, in most jurisdictions, no horizontal effect in the legal relation between employer and employees or unions.

There are many labor relations consultancies worldwide. They specialize in industries such as entertainment (radio, television and motion picture), hospitality (culinary and food service), communications, manufacturing, aerospace, utilities, and healthcare. Although many operate only in the United States, trade union organizing takes place multi-nationally. According to the AFL-CIO, "one of the largest U.S. firms, Labor Relations Institute (LRI),[3] offers a "Guaranteed Winner Package": if the corporation does not "win", it does not pay.[4] In both the US and Europe, organizing campaigns increasingly involve immigrant non-English speaking workers.[citation needed] Internationally, compliance with labor laws within developed countries can be vastly different from emerging countries. Both trade union organizers and management must know the law and avoid unfair labor practice (ULP) charges.

Application and adherence to labor laws may differ worldwide, but labor laws continue to expand into new countries such as the Labour Law of the People's Republic of China and the Indian labour law. Trade union organizing often starts with workers who are untrained or unaware of labour law. Due to the changing global and multinational employment environment and labor relations/employment laws, the modern labor movement turns more and more to professional guidance. Internationally, laws differ in how a bargaining unit is defined for workers with job descriptions involving supervision or management. Because the operative word is "law", trade unions and workplaces may retain legal counsel to navigate the complexities of local and/or international labor laws in order to avoid unfair labor practice charges.

History

editUnited Kingdom

editFollowing the repeal of the Combination Laws in 1824, workers were no longer prohibited from forming labor organizations or collective bargaining, although significant restrictions remained. In 1832 the Friendly Society of Agricultural Labourers was formed in Dorset to challenge declining wages. The members of the organization agreed to only work for wages greater than a certain amount. In 1834 a landlord complained, and key members were charged and convicted under laws prohibiting the swearing of secret oaths. The sentence of seven years penal transportation to Australia prompted a movement to defend the members, known as the Tolpuddle Martyrs (referring to the village where the organization originated), who were eventually released in 1836 and 1837.[5]

Presently, UK labor laws are defined within the Employment Relations Act 1999 (ERA) and the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992, and give workers no right to strike[citation needed]. In the UK and EU, trade union opposition may occur during automatic recognition campaigns and ballot elections. Workers in the UK may have union memberships that they retain job to job, potentially resulting in workers for the same employer having different union memberships. When a union is seeking to gain control of the collective bargaining at a place of employment without a ballot, workers with either individual and/or different union memberships working for that same employer may oppose that union.

Consultation is the process by which management and employees (or their representatives) jointly examine and discuss issues of mutual concern. It involves seeking acceptable solutions to problems through an exchange of views and information. Consultation does not remove the right of managers to manage, but it does impose an obligation that the views of employees be sought and considered before decisions are taken. The Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service (ACAS), is the UK government's independent agency for advice and conciliation. Although the Trade Union Congress (TUC) and their member unions oppose the use of consultancies during recognition campaigns, calling it a union busting tactic, ACAS takes a different stance, "Employee communications and consultation are the lifeblood of any business.[6] which "aims to improve organizations and working life through better employment relations".[7]

Derecognition of a trade union, while legal, may be referred to as union busting by trade unions. Derecognition must be accomplished according to statutory guidelines. Workers may derecognize a union which either no longer has support from its members, or if union membership falls below 50%. Employers may derecognize a union if they no longer employ 21 or more workers. If the Central Arbitration Committee (CAC) accepts an application, and the union in question has either lost support or the membership level falls below 50% of the workers, the CAC can declare that a derecognition ballot be held."[8]

2005 Heathrow union busting

editOne of the most significant cases of mass dismissals in the UK occurred in 2005, involving the termination of over 600 Gate Gourmet workers at Heathrow Airport. Gate Gourmet provides in-flight meals and had been owned by Texas Pacific since 2002. The company had been in talks with the Transport and General Workers' Union (TGWU) over redundancies and changes to overtime pay to try and stem losses when it hired 130 seasonal staff on lower wages than the permanent workers. Seeing this as a threat to their jobs, one shift refused to go back to work. Because this was seen as unofficial strike action, the workers were sacked, reportedly with only three minutes notice.[9][10] The TUC later reported that the dispute had been engineered by the company to allow it to replace staff with workers on worse contracts.[11]

This mass dismissal was viewed by some as a union busting tactic,[12][13] and caused a great deal of media scrutiny. The terminations prompted a walkout by British Airways ground staff that paralysed flights and stranded thousands of travellers in the UK.[13][14] The BBC reported that Andy Cook, Gate Gourmet's director of human resources at the time, said "the company had not been looking to cut the size of the protests, only stop the minority engaged in harassment."[15] Cooke continues to direct labor relations activities from his UK labor relations consultancy.[16]

A deal was brokered between Gate Gourmet and the TGWU by the TUC in September 2005.[17]

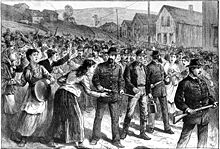

United States

editUnion busting in the United States dates at least to the 19th century, when a rapid expansion in factories and manufacturing capabilities caused a migration of workers from agricultural work to the mining, manufacturing and transportation industries. Conditions were often unsafe, women worked for lower wages than men, and child labor was rampant. Because employers and governments did little to address these issues, labor movements in the industrialized world were formed to seek better wages, hours, and working conditions. The clashes between labor and management were often adversarial and were deeply affected by wars, economic conditions, government policies, and court proceedings.

Companies may influence unions through bargaining, labor relations, and by other means, but employer-controlled unions in the United States have been outlawed since the National Labor Relations Act of 1935. The act prohibits supervisors from joining unions as well as prohibiting employers from assisting (as in the event of unions competing in the organization of a company), or dominating any labor organization.[18] Additionally, the two laws, passed in 1947 and 1959, respectively, were the Taft–Hartley Act and the Landrum–Griffin Act. These statutes guarantee the rights of private employees to form and join unions in order to bargain collectively. The vast majority of states have extended union rights to public employees.[19] The Chamber of Commerce has a long history of anti-union lobbying and union-busting in the United States at the local and federal level.[20][21][22]

Nathan Shefferman published The Man in the Middle, a 292-page account of his union busting activities, in 1961. Shefferman described a long list of practices which he viewed as tangential to union avoidance activities but which his detractors have labeled as support operations for these activities. Among these were the administration of opinion surveys, supervisor training, employee roundtables, incentive pay procedures, wage surveys, employee complaint procedures, personnel records, application procedures, job evaluations, and legal services. As part of his union busting strategies, all of these activities were performed with the goal of maintaining complete control of the work force by top management. Shefferman's book not only provided the concepts that animated all future union busting techniques, he also provided language that pro-labor supporters believe mask the intent of the policies.[23]

In 1962 US President John F. Kennedy issued Executive Order 10988,[24] which established the right for public sector employees to form unions with certain limitations regarding collective bargaining and a special caveat making it illegal to strike (later enacted into law as ). In 1981 the public sector union PATCO (Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization) went on strike in violation of Kennedy's executive order. President Reagan exercised his power and fired all the striking members, causing the dissolution of the union. Although the firing was legal, he was criticized by labor organizations for union busting.[25] PATCO reformed to become the National Air Traffic Controllers Association. Anti-union policies varies from state in the US with generally more worker protections in Democratic states when compared to Republican states.[26][27][28][29] Donald Trump Republican former president has publicly stated that he is against worker protections and stated his support for union-busting while doing an interview with Elon Musk.[30][31][32][33]

In the US, unlike the UK and several other countries, the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) provides a legally protected right for private sector employees to strike in order to gain better wages, benefits, or working conditions without the threat of termination. However, striking for economic reasons (i.e., protesting workplace conditions or supporting a union's bargaining demands) allows an employer to hire permanent replacements. If hired, the replacement worker can continue in the job, while the striking worker must wait for a vacancy. However, if the strike is due to unfair labor practices, the strikers replaced can demand immediate reinstatement at the end of the strike. If a collective bargaining agreement is in effect, and it contains a "no-strike clause", a strike during the life of the contract could result in the firing of all striking employees, and the dissolution of that union. Although legal, it is viewed by labor organizations as union busting.

Another common tactic is flooding the would be bargaining unit with new workers that are threatened and/or incentivised to avoid discussing the unionisation drive to refuse to sign cards or vote for the union, which can include importing workers with language skills uncommon to the workplace to drive a further wedge between the two sets of employees. Corporate headquarters staff can be assigned to individual units of the business in order to provide significantly increased surveillance of staff with the goal to reduce unionisation efforts and to find sham reasons to write up and fire organisers. These tactics often increase the cost to run the area in question significantly above what the unions would negotiate for but in the long term are viewed as acceptable in order to smash unions and prevent them taking a foothold. In worse case scenarios, entire stores may be closed under the auspices of "safety issues" or "redevelopment" and workers fired or diluted between multiple stores while also serving as a warning to other stores & workers that the company would rather fire them then have to negotiate with a union. In the United States businesses receive little pushback from regulator agencies and when violations are found they are often appealed and eventually dismissed or downplayed by judges, or are insignificantly punishing to prevent the illegal tactics being re-used.

Germany

editNGG, the German union for restaurant and food workers in 1999 used the notion of union busting to characterize the practices of McDonald's in Germany to kick out employees' representative bodies (Betriebsräte) and to prevent the voting of such representative bodies. However, only the study Union Busting in Deutschland (Union Busting in Germany) by Werner Rügemer and Elmar Wigand introduced the notion and presented an analysis of union busting. The study was commissioned by the largest German union, the metal workers union IG Metall and has been published in 2014.[34]

Rügemer and Wigand also referred in their study to US authors such as John Logan, Kate Bronfenbrenner, Martin Jay Levitt, and Joseph McCain. Subsequently, the authors published a much expanded and updated version in form of a book with the title Die Fertigmacher. Arbeitsunrecht und die professionelle Bekämpfung der Gewerkschaften (Union Busting, Labor Injustice and The Professional Fight Against Trade Unions).[35] After this, the notion union busting is used routinely in the media and by all German unions.

Rügemer and Wigand defined union busting in the following sentences: "Union Busting is the purposeful application and modular combination of practices to prevent employer-independent organization and advocacy in a company. Another point is to prevent (sabotage) the industry. Union Busting is operated both to attack the achieved status quo of collectivity, participation and labor protection. As well as to end organizing efforts of employees already in the initial stage."[36]

Later, Rügemer and Wigand founded the non-profit association Action Against Labour Injustice. The organization works for dependent employees and in particular works-councils.[37] The target group are the people affected by union busting and other forms of work inequalities. The association helps the victims with public actions and by legal. Prominent examples for union busting in Germany are Amazon.com, Birkenstock, Legoland, Haticon, Nora Systems, United Parcel Systems, Charité/Vivantes, Neupack, Edeka, DURA Automotive Systems, Median, Maredo, H&M and OBI.

Derecognition or decertification of trade unions

editDerecognition (UK) or decertification (US) of a union may be done lawfully, though these may be referred to as union busting by trade unions, even when it is initiated by members of the union.

Workers in the UK may derecognize a union that no longer has support from members or if union membership falls below 50%. Employers may derecognize a union if they no longer employ 21 or more workers. Generally, in the UK, an application for derecognition must be made to the Central Arbitration Committee (CAC), which declares that a derecognition/decertification ballot election will be held.[8] However a company may decide to unilaterally derecognize, as long as it has a non-CAC recognition agreement in force.[38]

In the US, the process is overseen by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). Employees may file a petition seeking a decertification election to determine whether or not the employees wish to retain the union. Like an election petition, a petition for decertification can only be filed during certain timeframes, specifically when a contract has expired or is about to expire.[39]

In Canada all provinces have laws setting out provisions for employees to decertify unions. In most cases the governments have made it mandatory that employers post information for its employees on how to decertify the union.[40]

Labor attorneys and consultancies

editOrganizations retain labor/employment attorneys and consultancies based on experience, track record, language skills, and reputation. Additionally, since labor laws differ from one nation to another, an organization might also consider experience with international labor laws within multinational corporations.

When trade union organizing occurs, labor attorneys are generally contacted for advice and often turn to consultants with whom they work on a regular basis who can do supervisory training on site.[41][42] Some companies keep labor relations consultants and attorneys on retainer while others use external labor/employment lawyers and/or consultancies on an hourly per diem basis.

Many labor lawyers and consultants find clients by monitoring government offices such as the NLRB regional offices, where US trade unions are required to file RC (Representation Certification) or RD (Representation Decertification) petitions which are public record.[43] These petitions reveal the names of organizations undergoing concerted activity and the name of the union seeking recognition or an election.[44] These petitions are also used by organizations to conduct demographic studies of concerted activity regionally in order to prepare supervisory training in anticipation of organizing. Some companies maintain libraries and offer petition logs online as a courtesy for companies which cannot conduct the research themselves.[45]

Similarly, UK trade unions are required by the ERA 1999 to adhere to specific procedures regarding trade union recognition, such as filing a "Letter of Intent" to the CAC,[46] which simultaneously notifies not only the CAC but the employer as well. The filing then becomes public record which labor lawyers and consultancies can access in order to market their services.

Unions as union busters

editThe International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT), as an employer, refused to negotiate in 2011 with a group of its own union organizer employees who voted to form a union called the Federation of Agents and International Representatives (FAIR).[citation needed] On 29 August 2012, after being found guilty of unlawfully union busting their own employees' union, the IBT posted a notice [47] that, according to an agreement approved by a regional director of the Obama administration's NLRB, that they would stop union busting. The notice assures Teamster employees that they will no longer be prevented from exercising their rights.

In an action involving the Retail Clerks International Association (RCIA, a part of the AFL-CIO), they lost their case when the NLRB found that the RCIA violated the NLRA by refusing to bargain with the representative of certain of its employees and by threatening employees with loss of their jobs unless they resigned from the union. The Board further found that the RCIA had violated Section 8(a) (1) by engaging in coercive conduct with respect to certain of its own employees.[48]

In the book Labor Organizations as Employers: Unions Within Unions, the author explored three different unions and the struggle of their workforces to organize. Prompted largely by the same concerns which motivate employees of private and public employers to seek union protection, employees within several unions, the United Transportation Union (UTU), the Garment Workers (ILGWU), and the Textile Workers (TWUA) were thwarted in their attempts to organize.[49][50]

Another recent example of union busting tactics used by one union against the other is the SEIU vs CNA conflict, where each union was battling for the others' members. In a press release dated March 10, 2008 Andy Stern of the SEIU accused the CNA of union busting: "The California Nurses Association has launched an anti-union campaign against nurses and other healthcare employees in Ohio, seeking to derail a three-year effort by the workers to unite in District 1199 of the Service Employees International Union."[51] Central to the SEIU-CNA dispute were accusations by both organizations of raiding each other's members and campaigns, as well as disagreements about the direction of the labor movement. The SEIU is focused in its mission to organize workers at any cost, provoking criticism for its consolidation of smaller locals into mega unions.[52]

Intelligence operations

editSome corporations have sought to learn of union activities by employing informants,[53][54][55] the same way that unions employ salts to infiltrate a non union organization to gather propaganda and sow discord to gain union support. A plant or salt can be used to disrupt meetings, question the legitimacy and motives of either the union or management, and report the results of the meetings to their superiors. Disruption or reporting on union meetings is illegal, but can be difficult to prove in ULP hearings.[56]

In 1980, the author of Confessions of a Union Buster, Martin J. Levitt, reported that he conducted a counter-organizing drive at a nursing home in Sebring, Ohio. He assigned confederates to scratch up cars, then blamed it on the union. Similar activities have not been reported by others, yet Levitt said that creating and exploiting a prolonged climate of fear was key for him destroying the union's credibility.[57]

In the United States, the US Supreme Court has upheld the decision of the National Labor Relations Board that employer espionage or an employer's use of spies or agents within labor unions is an unfair labor practice under the Wagner Act.[58]

Legal actions

editLabor consultants, union organizers, and attorneys use rules and regulations to gain control of organizing drives. Most employers oppose union plans for card check elections and employ tactics to insure secret ballot elections instead.[59] If the union focuses on one division of the company, employment lawyers may disrupt such plans and dilute the vote by petitioning the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) to include other divisions. If the union seeks to include foreman or "junior supervisor" positions in a bargaining unit to increase membership, the definition of what constitutes a supervisor under the NLRA [60] will often be challenged by employment or new staff added to dilute the strength of the organisers. Even the jurisdiction of the NLRB to oversee an organizing drive may be challenged. Delays can turn an organizing campaign into a protracted struggle, and according to Martin J. Levitt such battles are almost always won by management.[61]

Many of the methods for defeating unions have been practiced for a very long time. Harry Wellington Laidler wrote a book in 1913 which reported the use of delaying tactics and provocation by an undercover operative of one of the largest known agencies of the time called Corporations Auxiliary Company. They would tell prospective employers,

Once the union is in the field its members can keep it from growing if they know how, and our man knows how. Meetings can be set far apart. A contract can at once be entered into with the employer, covering a long period, and made very easy in its terms. However, these tactics may not be good, and the union spirit may be so strong that a big organization cannot be prevented. In this case our man turns extremely radical. He asks for unreasonable things and keeps the union embroiled in trouble. If a strike comes, he will be the loudest man in the bunch, and will counsel violence and get somebody in trouble. The result will be that the union will be broken up.[62]

Lockouts

editEmployers may put pressure on a union by declaring a lockout, a work stoppage in which an employer prevents employees from working until certain conditions are met. A lockout changes the psychological impact of a work stoppage and, if the company possesses information about an impending strike, can be enacted prior to the strike's implementation.[63]

Use of public funds in the United States

editAlthough nonprofit hospital workers were covered by the original Wagner Act of 1935, they were excluded in 1947 with the Taft–Hartley amendments. However, during the 1960s, hospital workers at nonprofit hospitals wanted to form unions in order to demand better pay and working conditions. Major American cities were also experiencing hospital strikes which raised awareness of both labor leaders and the government regarding how to continue life-sustaining patient care delivery during work stoppages.[64] Hospital workers and labor leaders petitioned the government to amend the NLRA. In 1974, under President Richard Nixon, the NLRA was amended[65] to extend coverage and protection to employees of non-profit hospitals. According to the Obama administration NLRB, "When the new legislation was considered by the Senate Committee on Labor and Public Welfare, it was recognized that labor relations in the health care industry required special considerations. The Senate Labor Committee sought to fashion a mechanism which would insure that the needs of the patient would be met during contingencies arising out of labor disputes. The new law represented a sound and equitable reconciliation of these competing interests."[66]

Taxpayer funds provide state treasuries the monies for public employee salaries from which public employees pay union dues. At one time state laws did not allow government contracts to provide public money to labor relations consultancies. One such law, passed in Wisconsin in 1979, was struck down by the United States Supreme Court in the decision Wisconsin Dept. of Industry v. Gould.[67] In effect, the 1986 Supreme Court decision meant that federal punishments are the maximum allowed, regardless of their limitations. Critics charged that, in effect, "federal labor law forces states to hire unionbusters."[68]

In 1998, Catholic Healthcare West, the largest private hospital chain in California and a major recipient of state Medicaid funds, conducted a campaign against the SEIU in Sacramento and Los Angeles at a cost of more than $2.6 million. After the Catholic Healthcare West campaign, the California state legislature passed a law prohibiting employers receiving more than $10,000 in state funds from engaging in anti-union activities.[69] However, the 2007 US Supreme Court decision in Chamber of Commerce of the United States of America et al. vs. Brown, Attorney General of California et al., the court ruled 7–2 that federal labor law pre-empted a California law that limited many employers from speaking to their employees about union-related issues. Justice John Paul Stevens stated that Federal labor law had embraced "wide-open debate" about labor issues, as long as the employer did not try to coerce employees into accepting its point of view. Consequently, the state law is incompatible with federal labor law.[70]

Other efforts to restrict anti-union activities by recipients of state funds have also been struck down. A major recipient of state Medicaid funds, the Center for Cerebral Palsy in Albany, New York, hired a law firm to fight a UNITE organizing drive. In 2002 the State of New York passed a labor neutrality act prohibiting the use of taxpayer dollars for union busting. The law was passed as a direct result of the campaign against UNITE. In May 2005, a district court judge struck down the labor neutrality law in a ruling that the legal representatives of the Center for Cerebral Palsy described as "an enormous victory for employers".[69]

Industrial psychologists as union busters

editNathan Shefferman introduced some basic psychological techniques into the union avoidance industry and the complementary service of union prevention. Building upon his work, professionally trained psychologists in the 1960s began using sophisticated psychological techniques to "screen out potential union supporters, identify hotspots vulnerable to unionization, and structure the workplace to facilitate the maintenance of a non-union environment."[69] These psychologists provided companies with psychological profiles and conducted audits concerning a firm's susceptibility to unionization.[69]

Between 1974 and 1984, one firm trained over 27,000 managers and supervisors to "make unions unnecessary" and surveyed almost one million employees in 4,000 organizations.[69]

Anti-union employers' organizations in the United States

editIn the United States shortly after 1900, there were few effective employers' organizations that opposed the union movement. By 1903, these organizations started to coalesce, and a national employers' movement began to exert a powerful influence on industrial relations and public affairs.[71]

For nearly a decade prior to 1903, an industrial union called the Western Federation of Miners (WFM) had been increasing in power, militancy, and radicalism in response to dangerous working conditions, the imposition of long hours of work, and what members perceived as an imperious attitude on the part of employers. In particular, members of the WFM had been outraged by employers' use of labor spies in organizing efforts such as Coeur d'Alene. The miners' frustrations had occasionally exploded in anger and violence, although they had also tried peaceful change. For example, after winning a referendum vote for the eight-hour day with support from 72 percent of Colorado's electorate, the WFM's goal of an eight-hour law was still defeated by employers and politicians.[72][73]

In 1901, angry WFM members passed a convention proclamation that a "complete revolution of social and economic conditions" was "the only salvation of the working classes".[74] Colorado employers and their supporters reacted to growing union restlessness and power in a confrontation that came to be called the Colorado Labor Wars.[75] But fear and apprehension on the part of employers, who felt unions were threatening to their businesses, were by no means limited to Colorado. Across the nation, the first elements of a network of employers' organizations that would span the coming century were just beginning to arise.

Anti-union organizations played increasingly prominent roles in American politics. In April 1903, David M. Parry spoke to the annual convention of the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM),[76] delivering a speech critical of organized labor, asserting that trade unionism and socialism differ only in method, with both aiming to deny "individual and property rights". Parry asserted the natural laws which governed the nation's economy, and he decried any interference with those laws, whether by legislative or other means. Parry asserted that the goals of the unions would inevitably lead to "despotism, tyranny, and slavery", and the "ruin of civilization".[77]

To control this threat to the status quo, Parry advised that the NAM begin organizing employers and manufacturers' associations into a great national anti-union federation. The NAM convention agreed to the recommendation, and created an employers' organizing committee with Parry in charge. Parry began the organizing effort at once.[78] The prospect of a federal eight-hour law was particularly objectionable to the NAM, which declared it a "vicious, needless, and in every way preposterous proposition."[79]

The NAM has fought against organized labor for more than a century through affiliated organizations.[80] However, the organization once sought to moderate its image. After the 1937 La Follette Committee investigated employers and their anti-union allies, uncovering widespread abuses, the NAM denounced "the use of espionage, strikebreaking agencies, professional strikebreakers, armed guards, or munitions for the purpose of interfering with or destroying the legitimate rights of labor to self organization and collective bargaining."[81] The brief nod to union rights did not last.

Other anti-union organizations have also made vocal contributions to anti-union discourse and union busting activities. The Citizens' Alliance was an employers' organization formed early in the 1900s specifically to fight trade unions. It worked with the NAM to strengthen anti-union movements in the early 20th century in the United States.[citation needed] The Council on Union Free Environment (CUE) had the specific mission of defeating President Carter's labor law reform bill that was designed to make union-organizing efforts more successful by, among other provisions, allowing for elections to occur within 15 days of filing a petition.[80] The Labor Law Study Group, later called the Construction Users Anti-Inflation Roundtable, introduced dozens of labor law reform bills in the US Congress, but their primary focus was repealing state and federal laws that established minimum wage standards on publicly funded projects. Associated Builders and Contractors (ABC)[82] is the construction industry's voice and is funded chiefly by non-union builders and related businesses and promoted the "merit shop" which sought to pay each employee according to his qualification and performance.[83] While the group insisted it was not anti-union, the system would preclude workers from exercising many of the worker-related benefits of a union.[83]

Other groups, such as the National Right to Work Committee, has lobbied for laws prohibiting the union shop. Similarly, the US Chamber of Commerce's core purpose is to fight for free enterprise before Congress, the White House, regulatory agencies, the courts, the court of public opinion, and governments around the world and has actively lobbied against the Employee Free Choice Act.[84] The NLPC[85] makes a case for the end of the use of union dues for political purposes. The Center for Union Facts maintains an anti-union website that provides financial and other records about unions.

See also

edit- Anti-union violence and union violence

- Captive audience meeting

- Confessions of a Union Buster

- Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise Convention, 1948

- Opposition to trade unions

- Salt (union organizing)

- Trade union prevalence worldwide

United States

References

edit- ^ *Smith, Robert Michael (2003). From blackjacks to briefcases: a history of commercialized strikebreaking in the United States. Athens OH: Ohio University Press. pp. 179. ISBN 978-0-8214-1466-8.

- Norwood, Stephen Harlan (2002). Strikebreaking & intimidation: mercenaries and masculinity in twentieth-century America. UNC Press. pp. 328. ISBN 978-0-8078-5373-3.

- Gall, Gregor (2003). "Employer opposition to union recognition". In Gregor Gall (ed.). Union organizing: campaigning for trade union recognition. London: Routledge. pp. 79–96. ISBN 978-0-415-26781-6.

- ITUC. "2010 Annual survey of violations of trade union rights". International Trade Union Confederation. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ^ "The Universal Declaration of Human Rights". Archived from the original on 2014-12-08. Retrieved 2022-09-22.

- ^ [Labor Relations Institute],"Union Avoidance Video | Guaranteed Winner «". Archived from the original on 2012-01-02. Retrieved 2012-01-14.

- ^ [AFL-CIO],"The Ugly Face of Union-Busting | AFL-CIO NOW BLOG". Archived from the original on February 23, 2012. Retrieved January 14, 2012.

- ^ Martys' Story, Tolpuddle Martyrs' Museum, retrieved 12 June 2010

- ^ "Help and advice for employers and employees". www.acas.org.uk. 2019-06-27. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ "Representation | Advice and guidance | Acas". www.acas.org.uk. 2008-02-15. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ a b "Working with trade unions: employers". GOV.UK. Retrieved 2019-06-28.

- ^ James Arrowsmith (19 September 2005). "British Airways' Heathrow flights grounded by dispute at Gate Gourmet". Eurofound. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Kevin Ovenden (13 August 2005). "Defiance at Heathrow as strike forces talks". Socialist Worker. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ "Congress Report 2005: The 137th annual Trades Union Congress" (PDF). Trades Union Congress. September 2005. p. 29. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ The Walrus (September 2005). "Heathrow Dispute: Bring the Bosses Down to Earth". Socialist Review. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ a b "Workers worldwide back their Heathrow colleagues". International Transport Workers' Federation. 12 August 2005. Archived from the original on 2 April 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ "Wildcat strike protests mass sackings at Heathrow". International Communist League. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ "Gate Gourmet loses picket ruling". 2005-08-21. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ [Marshall James website], "Marshall James-The Employee Relations Specialists". Archived from the original on December 2, 2011. Retrieved January 10, 2012.

- ^ Miles Costello (27 September 2005). "Gate Gourmet and unions reach deal". The Times. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ John A. Fossum, Labor Relations -- Development, Structure, Process, 1982, page 74.

- ^ "Labor Law Questions and Answers - eNotes.com". eNotes. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ "Union Busters Operate in Secret — and Want to Keep It That Way".

- ^ "Search Registrations & Quarterly Activity Reports | Lobbying Disclosure".

- ^ "U.S. Chamber of Commerce - June 20 - Letter Opposing the "Employee Free Choice Act"". Archived from the original on 2008-12-05.

- ^ Confessions of a Union Buster, Martin Jay Levitt, 1993, page 38-39.

- ^ "Executive Order 10988—Employee-Management Cooperation in the Federal Service | The American Presidency Project". www.presidency.ucsb.edu. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ "20. The Air Traffic Controllers' Strike". eightiesclub.tripod.com. Archived from the original on 2011-05-10. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ "Labor Movement Condemns Georgia Republicans' Outrageous Voter Suppression Law | AFL-CIO". aflcio.org. March 26, 2021.

- ^ "Democratic Party Still Seen as Better for Union Members". Gallup.com. September 9, 2024.

- ^ Slott, Mike (July 27, 2016). "Democrats Support, Republicans Oppose Labor Unions in their Party Platforms". Health Professionals & Allied Employees.

- ^ Nadeem, Reem (February 1, 2024). "3. Labor unions".

- ^ "On overtime pay, Trump slips up by accidentally telling the truth". MSNBC.com. September 30, 2024.

- ^ Lyons, Kim (September 29, 2024). "Trump ramps up personal attacks on Harris during Erie rally, and says he 'hated' paying overtime • Pennsylvania Capital-Star".

- ^ "Watch: Trump Proudly Brags About How He Got Out of Paying Workers". The New Republic – via The New Republic.

- ^ "Trump and Musk discussed firing striking workers. The UAW is now seeking an NLRB investigation". PBS News. August 13, 2024.

- ^ "Union Busting in Deutschland". Otto Brenner Stiftung. Archived from the original on 2017-12-13. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- ^ Werner Rügemer, Die Fertigmacher (Union Busting. Labour injustice and the professional fight against trade unions), Köln 2014

- ^ Werner Rügemer/Elmar Wigand (2017), Die Fertigmacher: Arbeitsunrecht und professionelle Gewerkschaftsbekämpfung (in German) (3 ed.), Köln: Papy Rossa, ISBN 978-3894385552

- ^ http://www.https Archived 2013-08-19 at the Wayback Machine://arbeitsunrecht.de/.html

- ^ "Joining a trade union". GOV.UK. Retrieved 2019-06-28.

- ^ "What can I do if I'm unhappy with my union? | NLRB". Archived from the original on June 5, 2012. Retrieved March 27, 2012.

- ^ "Canadian Union, Collective Bargaining Laws". www.canadianlawsite.ca. Retrieved 2019-06-28.

- ^ "USLAW NETWORK, Inc". USLAW NETWORK, Inc. Retrieved 2019-06-28.

- ^ Confessions of a Union Buster, Martin Jay Levitt, 1993, page 160.

- ^ "Who we are". National Labor Relations Board. Archived from the original on 2011-05-16. Retrieved 2022-09-22.

- ^ Confessions of a Union Buster, Martin Jay Levitt, 1993, page 8.

- ^ "LRI Online Elections Review". Labor Relations Institute. Archived from the original on 2012-01-02. Retrieved 2022-09-22.

- ^ "Guide to Statutory Recognition: Using the CAC Procedure" (PDF). UNISON. September 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 22, 2012. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- ^ "NLRB Tells Teamsters: Stop Harassing Organizers". Scribd. Retrieved 2019-06-28.

- ^ "Retail Clerks International Association, Afl-Cio, and Retail Clerks International Association, Local 880, Afl-Cio v. National Labor Relations Board, 366 F.2d 642 (D.C. Cir. 1966)". Archived from the original on 2012-07-07. Retrieved 2024-06-08.

- ^ Shair, David I (1970). "Labor Organizations as Employers: "Unions-Within-Unions"". The Journal of Business. 43 (3): 296–316. doi:10.1086/295283. JSTOR 2351780.

- ^ The Unionisation of Union Employees and Staff Members by Dr. Karl F. Treckel, Labor and Industrial Relations Series no. 1, Bureau of Economic and business Research (Kent, Ohio: Kent State University, undated

- ^ "SEIU: 'Union-Busting' by California Nurses Association -- re> COLUMBUS, Ohio, March 10 /PRNewswire-USNewswire/ --". Archived from the original on 2014-03-02. Retrieved 2012-02-23.

- ^ Dogood, Silence (2008-04-29). "The Union News.: SEIU violence justified v. union-busting union". The Union News. Archived from the original on 2014-03-09. Retrieved 2019-06-28.

- ^ Confessions of a Union Buster, Martin Jay Levitt, 1993, page 3. Emphasis added.

- ^ "Public Reaction to Pinkertonism and the Labor Question," J. Bernard Hogg, Pennsylvania History 11 (July 1944), 171--199, pages 175-176.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases — A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, page 82.

- ^ Confessions of a Union Buster, Martin Jay Levitt, 1993, page 103. Emphasis added for clarity.

- ^ Confessions of a Union Buster, Martin Jay Levitt, 1993, page 195.

- ^ Robert H. Wettach, Unfair labor practices under the Wagner Act, Law and Contemporary Problems, Spring 1938, p.229-230.

- ^ "Card check recognition: new house rules for union organizing?". Fordham Urban Law Journal. 2008.

- ^ "FindArticles.com | CBSi". findarticles.com. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ Confessions of a Union Buster, Martin Jay Levitt, 1993, pages 24-25, 58-59, and 174-175.

- ^ Harry Wellington Laidler, Boycotts and the labor struggle economic and legal aspects, John Lane company, 1913, pages 291-292

- ^ The Pinkerton Story, James D. Horan and Howard Swiggett, 1951, page 236.

- ^ "National Union of Hospital and Health Care Employees 1199 News Photographs". New York State Archives. Archived from the original on July 10, 2011.

- ^ "The 1974 Health Care Amendments to the National Labor Relations Act: Jurisdictional Standards and Appropriate Bargaining Units". Retrieved 2022-09-22.

- ^ [NLRA Amendment for hospital workers]"National Labor Relations Board, 75 Years, 1935 - 2010". Archived from the original on March 13, 2012. Retrieved January 11, 2012.

- ^ "FindLaw's United States Supreme Court case and opinions". Findlaw. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ See: "Progressive States Network | Labor Union Majority Signup Approved in OR & NH -- and States Demand the US Senate Follows Suit". Archived from the original on August 9, 2007. Retrieved June 17, 2007. Retrieved June 17, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e "The Union Avoidance Industry in the United States", British Journal of Industrial Relations, John Logan, Blackwell Publishing Ltd, December 2006, pages 651–675.

- ^ "CHAMBER OF COMMERCE OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ET AL. v. BROWN, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF CALIFORNIA" (PDF). Retrieved 2022-09-22.

- ^ Colorado's War on Militant Unionism, James H. Peabody and the Western Federation of Miners, George G. Suggs, Jr., 1972, page 65-66.

- ^ Anthony Lukas, Big Trouble, 1997, pages 218-220.

- ^ Roughneck— The Life and Times of Big Bill Haywood, Peter Carlson, 1983, page 65.

- ^ All That Glitters—Class, Conflict, and Community in Cripple Creek, Elizabeth Jameson, 1998, page 179.

- ^ Colorado's War on Militant Unionism, James H. Peabody and the Western Federation of Miners, George G. Suggs, Jr., 1972, page 65.

- ^ "NAM | National Association of Manufacturers". NAM. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ^ Colorado's War on Militant Unionism, James H. Peabody and the Western Federation of Miners, George G. Suggs, Jr., 1972, page 66-67. Emphasis added.

- ^ Colorado's War on Militant Unionism, James H. Peabody and the Western Federation of Miners, George G. Suggs, Jr., 1972, page 66-67.

- ^ A Union Against Unions: The Minneapolis Citizens Alliance and Its Fight Against Organized Labor, William Millikan, 2001, page 31.

- ^ a b Confessions of a Union Buster, Martin Jay Levitt, 1993, pages 146-147.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases — A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, page 96.

- ^ "Associated Builders and Contractors - National Office > ABC". www.abc.org. Retrieved 2019-06-28.

- ^ a b Confessions of a Union Buster, Martin Jay Levitt, 1993, page 146.

- ^ "U.S. Chamber of Commerce - June 20 - Letter Opposing the "Employee Free Choice Act"". Archived from the original on December 5, 2008. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- ^ "NLPC Organized Labor Accountability Project". Archived from the original on September 14, 2008. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

External links

edit| External videos | |

|---|---|

| Union Busting: Last Week Tonight with John Oliver (HBO) on YouTube |