This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. (October 2019) |

Antonio de Solís y Ribadeneyra (18 July 1610 – 19 April 1686) was a Spanish dramatist and historian. His work includes drama, poetry, and prose, and he has been considered one of the last great writers of Spanish Baroque literature.

He was born at Alcalá de Henares (or, less probably, Plasencia). He studied law at Salamanca, where he produced a comedy entitled Amour and Obligation, which was acted in 1627. He became secretary to the count of Oropesa, and in 1654 he was appointed secretary of state as well as private secretary to Philip IV. Later he obtained the lucrative post of chronicler of the Indies, and, on taking orders in 1667 severed his connexion with the stage. He died at Madrid on 19 April 1686.[1]

His Work

editOf his ten extant plays, two have some place in the history of the drama. El Amor al uso was adapted by Scarron and again by Thomas Corneille as L'Amour de la mode, while La Gitanilla de Madrid, itself founded on the novela of Cervantes, has been utilized directly or indirectly by Pius Alexander Wolff, Victor Hugo and Longfellow.[1]

The titles of the remaining seven are Triumph from Armor and Fortune, Eurídice y Orfeo, The Alcetzar del secretion, The Amazons, The Doctor Carlino, Un bobo hace ciento and Defend the Enemy. Amor y obligación survives in a manuscript at the Biblioteca Nacional.[1]

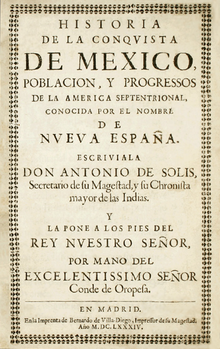

The Historia de la conquista de México, población y progresos de la América septentrional, conocida por el nombre de Nueva España, covering the three years between the appointment of Cortés to command the invading force and the fall of the city, deservedly ranks as a Spanish prose classic. It was first published in 1684 in Spain. French and Italian translations were published by the 1690s, and an English translation by Townshend appeared in 1724.[1] The book was extremely popular on both sides of the Atlantic and was known to important figures in colonial Latin America and the British colonies. It remained the most important European source on Latin American history up through the first part of the nineteenth century.[citation needed]

References

edit- ^ a b c d One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Solís, Antonio de". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 361–362.

Further reading

edit- Antonio de Solís; Thomas Townsend (1738). History of the Conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards. Historia de la conquista de Mexico.English.1738. London.

- One Fool Makes Many, a translation by Henry Vassall-Fox, 3rd Baron Holland of Un bobo hace ciento

- Cull, John. 2017. Mal haya el hombre que en refranes fía: Paremias in the Literary Works of Antonio de Solís. Paremia 26: 2017, pp. 179–190. ISSN 1132-8940. ISSN electrónico 2172-1068. Open access

- Works by Antonio de Solís y Ribadeneyra at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)