Andranik Ozanian,[B] commonly known as General Andranik[4][C] or simply Andranik;[D] (25 February 1865 – 31 August 1927),[E] was an Armenian military commander and statesman, the best known fedayi[1][5][7] and a key figure of the Armenian national liberation movement.[8] From the late 19th century to the early 20th century, he was one of the main Armenian leaders of military efforts for the independence of Armenia.

Andranik Անդրանիկ | |

|---|---|

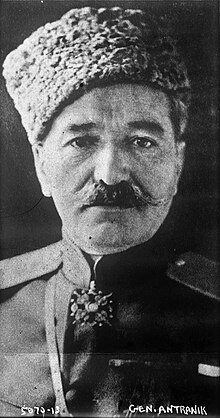

General Andranik Ozanian, wearing his uniform and medals with a papakha hat | |

| Nickname(s) | Andranik pasha[1] |

| Born | 25 February 1865 Shabin-Karahisar, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 31 August 1927 (aged 62) Richardson Springs, California, U.S. |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | Armenian paramilitaries (1917–19) |

| Years of service | 1888–1907 (fedayi) 1912–13 (Bulgaria) 1914–16 (WWI) 1917–19 (Armenia) |

| Rank | Commander of the fedayi (1899–1904)[2] Commander of the Western Armenian division of the Armenian Army Corps (1918) Commander of the Special Striking Division (1919) |

| Wars | |

| Awards | see below |

| Signature | |

He became active in an armed struggle against the Ottoman government and Kurdish irregulars in the late 1880s. Andranik joined the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Dashnaktustyun) party and, along with other fedayi (militias), sought to defend the Armenian peasantry living in their ancestral homeland, an area known as Western (or Turkish) Armenia—at the time part of the Ottoman Empire. His revolutionary activities ceased and he left the Ottoman Empire after the unsuccessful uprising in Sasun in 1904. In 1907, Andranik left Dashnaktustyun because he disapproved of its cooperation with the Young Turks, a party which years later perpetrated the Armenian genocide. Between 1912 and 1913, together with Garegin Nzhdeh, Andranik led a few hundred Armenian volunteers within the Bulgarian army against the Ottomans during the First Balkan War.

From the early stages of World War I, Andranik commanded the first Armenian volunteer battalion within the Russian Imperial army against the Ottoman Empire, capturing and later governing much of the traditional Armenian homeland. After the Revolution of 1917, the Russian army retreated and left the Armenian irregulars outnumbered against the Turks. Andranik led the defense of Erzurum in early 1918, but was forced to retreat eastward due to an threat of encirclement and a lack of food. By May 1918, Turkish forces stood near Yerevan—the future Armenian capital—and were halted at the Battle of Sardarabad. The Dashnak-dominated Armenian National Council declared the independence of Armenia and signed the Treaty of Batum with the Ottoman Empire, by which Armenia gave up its rights to Western Armenia. Andranik never accepted the existence of the First Republic of Armenia because it included only a small part of the area many Armenians hoped to make independent. Andranik, independently from the Republic of Armenia, fought in Zangezur against the Azerbaijani and Turkish armies, and helped to keep it within Armenia.[9]

Andranik left Armenia in 1919 due to disagreements with the Armenian government and spent his last years of life in Europe and the United States seeking relief for Armenian refugees. He settled in Fresno, California in 1922 and died five years later in 1927. Andranik is greatly admired as a national hero by Armenians; numerous statues of him have been erected in several countries. Streets and squares were named after Andranik, and songs, poems and novels have been written about him, making him a legendary figure in Armenian culture.[10]

Early life

editAndranik Ozanian was born on 25 February 1865,[11] in the town of Shabin-Karahisar (Şebinkarahisar), Sivas Vilayet, Ottoman Empire, to Mariam and Toros Ozanian.[12] Andranik means "firstborn" in Armenian. His paternal ancestors came from the nearby village of Ozan (now Ozanlı) in the early 18th century and settled in Shabin-Karahisar to avoid persecution from the Turks.[12] His ancestors took the surname Ozanian in honor of their hometown. Andranik's mother died when he was one year old and his elder sister Nazeli took care of him. Andranik went to the local Musheghian School from 1875 to 1882 and thereafter worked in his father's carpentry shop.[13] He married at the age of 17, but his wife died a year later while giving birth to their son—who also died days after the birth.[12]

The situation of the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire had worsened under the reign of Abdul Hamid II, who sought to unify all Muslims under his rule.[14] In 1882, Andranik was arrested for assaulting a Turkish gendarme for mistreating Armenians. With the help of his friends, he escaped from prison. He settled in the Ottoman capital Constantinople in 1884 and stayed there until 1886, working as a carpenter.[15] He began his revolutionary activities in 1888 in the province of Sivas.[16][17] Andranik joined the Hunchak party in 1891.[18] He was arrested in 1892 for taking part in the assassination of Constantinople's police chief, Yusuf Mehmed Bey—known for his anti-Armenianism—on 9 February.[19] Andranik once again escaped from prison.[15] In 1892, he joined the newly created Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF or Dashnaktsutyun).[16][17] During the Hamidian massacres, Andranik with other fedayi defended the Armenian villages of Mush and Sasun from attacks of the Turks and the Kurdish Hamidiye units.[17][20] The massacres, which occurred between 1894 and 1896 and are named after Sultan Abdul Hamid II, killed between 80,000 and 300,000 people.[21]

In 1897, Andranik went to Tiflis—the largest city of the Caucasus and a major center of Armenian culture at the time—where the ARF headquarters was located.[17] Andranik returned to Turkish Armenia "entrusted with extensive powers, and with a large supply of arms" for the fedayi.[20] Several dozen Russian Armenians joined him, with whom he went to the Mush-Sasun area where Aghbiur Serob was operating.[22] Serob's forces had already established semi-independent Armenian areas by expelling the Ottoman government representatives.[8]

Leader of the fedayi

editAghbiur Serob, the main leader of the fedayi in the 1890s, was killed in 1899 by a Kurdish chieftain, Bushare Khalil Bey.[17] Months later, Bey committed further atrocities against the Armenians by killing a priest, two young men and 25 women and children in Talvorik, a village in the Sasun region.[22] Andranik replaced Serob as the head of the Armenian irregular forces "with 38 villages under his command" in the Mush-Sasun region of Western Armenia,[8] where a "warlike semi-independent Armenian peasantry" lived.[17] Andranik sought to kill Bey; he captured and reportedly decapitated the chieftain, and took the medal given to Bey by Sultan Abdul Hamid II.[22][23][20] Andranik thus earned an undisputed authority among his fedayi.[24]

Although small groups of Armenian fedayi conducted an armed struggle against the Ottoman state and the Kurdish tribes, the situation in Western Armenia deteriorated as the European powers stood indifferent to the Armenian Question. Article 61 of the 1878 Treaty of Berlin intended the Ottoman government to "carry out, without further delay, the improvements and reforms demanded by local requirements in the provinces inhabited by the Armenians, and to guarantee their security against the Circassians and Kurds" remained unimplemented.[25] According to Christopher J. Walker, the attention of the European powers was on Macedonia, while Russia was "in no mood for reactivating the Armenian question."[26]

Battle of Holy Apostles Monastery

editIn November 1901 the fedayi clashed with the Ottoman troops in what later became known as the Battle of Holy Apostles Monastery. One of the best-known episodes of Andranik's revolutionary activities, it was an attempt by the Ottoman government to suppress his activities. Since Andranik had gained more influence over the region, more than 5,000 Turkish soldiers were sent after him and his band. The Turks chased and eventually circled him and his men, numbering around 50, at the Arakelots (Holy Apostles) Monastery in early November. A regiment under the command of Ferikh Pasha and Ali Pasha besieged the fort-like monastery. The Turkish generals leading the army of twelve hundred men asked the fedayi to negotiate their surrender.[27]

After weeks of resistance and negotiations—in which Armenian clergy and the headman of Mush and foreign consuls took part—Andranik and his companions left the monastery and fled in small groups. According to Leon Trotsky, Andranik—dressed in the uniform of a Turkish officer—"went the rounds of the entire guard, talking to them in excellent Turkish," and "at the same time showing the way out to his own men."[17][28] After breaking through the siege of the monastery, Andranik gained legendary stature among provincial Armenians.[4][29] He became so popular that the men he led came to refer to him always by his first name.[30] Andranik intended to attract the attention of the foreign consuls at Mush to the plight of the Armenian peasants and to provide hope for the oppressed Armenians of the eastern provinces.[30] According to Trotsky, Andranik's "political thinking took shape in a setting of Carbonarist activity and diplomatic intrigue."[20]

1904 Sasun uprising and exodus

editIn 1903, Andranik demanded the Ottoman government stop the harassment of Armenians and implement reforms in the Armenian provinces.[31] Most fedayi were concentrated in the mountainous region of Sasun, an area of about 12,000 km2 (4,600 sq mi) with an overwhelming Armenian majority—1,769 Armenian and 155 Kurdish households—which was traditionally considered their main operational area.[32] The region was in "a state of revolutionary turmoil" because the local Armenians had refused to pay taxes for the past seven years.[8][33] Andranik and tens of other fedayi—including Hrayr and Sebouh—held a meeting at Gelieguzan village in the third quarter of 1903 to manage the future defense of the Armenian villages from possible Turkish and Kurdish attacks. Andranik suggested a widespread uprising of the Armenians of Taron and Vaspurakan; Hrayr opposed his view and suggested a small, local uprising in Sasun, because the Armenian irregulars lacked resources. Hrayr's suggestion was eventually approved by the fedayi meeting. Andranik was chosen as the main commander of the uprising.[34][33]

The first clashes took place in January 1904 between the fedayi and Kurdish irregulars supported by the Ottoman government.[34] The Turkish offensive started in early April with an estimated 10,000 to 20,000 soldiers and 7,000 Kurdish irregulars put against 100 to 200 Armenian fedayi and 700 to 1,000 local Armenian men.[35][36] Hrayr was killed during the intense fighting; Andranik survived and resumed the fight.[37] Between 7,000 and 10,000 Armenian civilians were killed during the two months of the uprising, while about 9,000 were left homeless.[38] Around 4,000 Sasun villagers were forced into exile after the uprising.[35]

After weeks of fighting and cannon bombardment of the Armenian villages,[35] the Ottoman forces and Kurdish irregulars suppressed the uprising by May 1904; they outnumbered the Armenian forces several times.[8][38] Minor clashes occurred thereafter.[38] According to Christopher J. Walker, the fedayi came "near to organising an uprising and shaking Ottoman power in Armenia," but "even then it was unthinkable that the empire would lose any of her territory, since the idea of intervention was far from Russia."[26] Trotsky wrote that international attention was on the Russo-Japanese War and the uprising went largely unnoticed by the European powers and Russia.[35]

In July–August 1904, Andranik and his fedayi reached Lake Van and got to Aghtamar Island with sailing ships.[39][35] They escaped to Persia via Van in September 1904,[39] "leaving little more than a heroic memory."[8] Trotsky states that they were forced to leave Turkish Armenia to avoid further killings of Armenians and to lower the tensions,[35] while Tsatur Aghayan wrote that Andranik left the Ottoman Empire because he sought to "gather new resources and find practical programs" for the Armenian struggle.[15]

Immigration and conflict with the ARF

editFrom Persia, Andranik moved to the Caucasus,[17] where he met the Armenian leaders in Baku and Tiflis. He then left Russia and traveled to Europe, where he was engaged in advocacy in support of the Armenians' national liberation struggle.[15][39] In 1906 in Geneva, he published a book on military tactics.[40] Most of the work was about his activities and the strategies he used during the 1904 Sasun uprising.[29]

In February–March 1907, Andranik went to Vienna to participate in the fourth ARF Congress. The ARF, which had been collaborating with Turkish émigré political groups in Europe since 1902, discussed and approved the negotiations with the Young Turks—who later perpetrated the Armenian genocide—to overthrow Sultan Abdul Hamid II. Andranik strongly denounced this cooperation and left the party.[8][41] In 1908, the ARF asked Andranik to move to Constantinople and nominate his candidacy in the Ottoman parliament election, but he declined the offer, saying "I don't want to sit there and do nothing."[11][42] Andranik distanced himself from active political and military affairs for several years.

First Balkan War

editIn 1907 Andranik settled in Sofia, where he met the leaders of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization—including revolutionary Boris Sarafov—and the two pledged to work jointly for the oppressed peoples of Armenia and Macedonia.[35][43] During the First Balkan War (1912–13), Andranik led a company of 230 Armenian volunteers— part of the Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Volunteer Corps of Aleksandar Protogerov within the Bulgarian army—against the Ottoman Empire.[17][44][45] He shared the command with Garegin Nzhdeh.[46] On the opposite side, approximately 8,000 Armenians fought for the Ottoman Empire.[47] Andranik was given the rank of a first lieutenant by the Bulgarian government.[39] He distinguished himself in several battles, including in the Battle of Merhamli, when he helped the Bulgarians to capture Turkish commander Yaver Pasha.[48][49] Andranik was honored with the Order of Bravery by General Protogerov in 1913.[49][50] However, Andranik disbanded his men in May 1913,[51] and foreseeing the war between Bulgaria and Serbia he "retired to a village near Varna, and lived as a farmer until August 1914."[39]

World War I

editWith the outbreak of World War I in July 1914 between Russia, France and Britain on one side and Germany, the Ottoman Empire and Austria on the other, Andranik left Bulgaria for Russia.[17] He was appointed the commander of the first Armenian volunteer battalion by the Russian government. From November 1914 to August 1915, Andranik took part in the Caucasus Campaign as the head commander of the first Armenian battalion of about 1,200 volunteers within the Imperial Russian Army.[52][49] Andranik's battalion particularly stood out at the Battle of Dilman in April 1915.[17] By the victory at Dilman, the Russian and Armenian forces under the command of General Nazarbekian, effectively stopped the Turks from invading the Caucasus via Iranian Azerbaijan.[49][53]

Through 1915, the Armenian genocide was underway in the Ottoman Empire.[53] By the end of the war, virtually all Armenians living in their ancestral homeland were either dead or forced into exile by the Ottoman government. An estimated 1.5 million Armenians died in the process, ending the Armenian presence in Western Armenia.[54][55] The only major resistance to the Turkish atrocities took place in Van.[56] The Turkish army besieged the city but the local Armenians, under the leadership of Aram Manukian, kept them out until the Armenian volunteers reached Van, forcing the Turks to retreat.[57] Andranik with his unit entered Van on 19 May 1915.[53] Andranik subsequently helped the Russian army to take control of Shatakh, Moks and Tatvan on the southern shore of Lake Van.[58] During the summer of 1915, the Armenian volunteer units disintegrated and Andranik went to Tiflis to recruit more volunteers and continued the combat from November 1915 until March 1916.[57] With Andranik's support, the city of Mush was captured by Russians in February 1916.[58] In recognition of lieutenant general Theodore G. Chernozubov, the successes of Russian army in numerous locations were significantly associated with the fighting of the first Armenian battalion, headed by Andranik. Chernozubov praised Andranik as a brave and experienced chief, who well understood the combat situation; Chernozubov described him as always at the head of militia, enjoying great prestige among the volunteers.[59]

The situation drastically changed in 1916 when the Russian government ordered the Armenian volunteer units to be demobilized and prohibited any Armenian civic activity.[56] Andranik resigned as the commander of the first Armenian battalion.[57] Despite the earlier Russian promises, their plan for the region was to make Western Armenia an integral part of Russia and "possibly repopulate by Russian peasants and Cossacks."[60] Richard Hovannisian wrote that because the "Russian armies were in firm control of most of the Armenian plateau by the summer of 1916, there was no longer any need to expend niceties upon the Armenians."[61] According to Tsatur Aghayan, Russia used the Armenian volunteers for its own interests.[57] Andranik and other Armenian volunteers, disappointed by the Russian policy, left the front in July 1916.[57]

Russian Revolution and Turkish reoccupation

editThe February Revolution was positively accepted by the Armenians because it ended the autocratic rule of Nicholas II.[59] The Special Transcaucasian Committee (known as OZAKOM) was set up in the South Caucasus by the Russian Provisional Government.[61] In April 1917, Andranik initiated the publication of the newspaper Hayastan (Armenia) in Tiflis.[59][62] Vahan Totovents became the editor of this non-partisan, Ottoman Armenian-orientated newspaper.[63] Until December 1917, Andranik remained in the South Caucasus where he sought to help the Armenian refugees from the Ottoman Empire in their search for basic needs.[57] The provisional government decree of 9 May 1917 put Turkish Armenia under civil administration, with Armenians holding key positions. About 150,000 local Armenians began to rebuild devastated Turkish Armenia; however the Russian army units gradually disintegrated and many soldiers deserted and returned to Russia.[61]

After the 1917 October Revolution, the chaotic retreat of Russian troops from Western Armenia escalated.[64] Bolshevik Russia and the Ottoman Empire signed the Armistice of Erzincan on 5 December 1917, ending the hostilities. The Soviet Russian government formally acknowledged the right of self-determination of the Ottoman Armenians in January 1918, but on 3 March 1918, Russia signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with the Central Powers, ceding Western Armenia and large areas in Eastern Europe to concentrate its forces against the Whites in the Russian Civil War.[65]

In December 1917, because the Russian divisions were deserting the region en masse, the Russian command authorized the formation of the Armenian Army Corps under the Transcaucasian Commissariat. Under the command of General Nazarbekian, the Corps was positioned in the front line from Van to Erzincan—a city of around about 20,000 people. Two of the Corps' three divisions were made up of Russian Armenians, while Andranik commanded the Turkish (Western) Armenian division.[66] The Georgian forces patrolled the area between Erzincan and the Black Sea. Hovannisian states that the only "several thousand men now defended a 300-mile front formerly secured by a half million Russian regulars."[67] Since December 1917, Andranik commanded the Armenian forces in Erzurum. In January 1918, he was appointed commander of the Western Armenian division of the Armenian Army Corps and given the rank of major-general by the Caucasus Front command.[3][11] Andranik was unable to defend Erzurum for long and the outnumbering Turks captured the city on 12 March 1918, forcing the Armenians to evacuate.[66][17]

While the Transcaucasian delegation and the Turks were holding a conference in Trebizond, through March and April the Turkish forces, according to Walker, "overran the temporary establishment of Armenian rule in Turkish Armenia, extinguishing the hope so recently raised."[66] Hovannisian wrote, "the battle for Turkish Armenia had been quickly decided; the struggle for Russian Armenia was now at hand."[68] After the Turks captured Erzurum, the largest city in Turkish Armenia, Andranik retreated through Kars, passed through Alexandropol and Jalaloghly, and arrived in Dsegh by 18 May.[11][69] By early April 1918, the Turkish forces had reached the pre-war international borders.[68] Andranik and his unit in Dsegh were not able to take part in the battles of Sardarabad, Abaran and Karakilisa.[69]

First Republic of Armenia

editAfter the Ottoman forces were effectively stopped at Sardarabad, the Armenian National Council declared the independence of the Russian Armenian lands on 28 May 1918. Andranik condemned this move and denounced the Armenian Revolutionary Federation.[70] Angry with the Dashnaks, he favored good relations with Bolshevik Russia instead.[17][69] Andranik refused to acknowledge the Republic of Armenia, which he regarded as little more than "a pawn in the grip of [Ottoman] Turkey․"[71] He condemned the singing of the Treaty of Batum (by which the Ottoman Empire recognized the independence of a greatly reduced Armenia and imposed a number of humiliating conditions) as an act of treason.[71] As Christopher Walker notes, many Turkish Armenians saw the new republic as "only a dusty province without Turkish Armenia whose salvation Armenians had been seeking for 40 years."[72] In early June, Andranik departed from Dilijan with thousands of refugees; they traveled through Sevan, Nor Bayazet and Vayots Dzor, and arrived in Nakhichevan on 17 June.[11] He subsequently tried to help the Armenian refugees from Van at Khoy, Iran. He sought to join the British forces in northern Iran, but after encountering a large number of Turkish soldiers he retreated to Nakhichevan.[11][71] On 14 July 1918, he proclaimed Nakhichevan an integral part of (Soviet) Russia. His move was welcomed by Armenian Bolshevik leader Stepan Shahumyan and Vladimir Lenin.[17][73]

Zangezur

editAs the Turkish forces moved towards Nakhichevan, Andranik with his Armenian Special Striking Division moved to the mountainous region of Zangezur to set up a defense.[11] By mid-1918, the relations between the Armenians and Azerbaijanis in Zangezur had deteriorated.[74] Andranik arrived in Zangezur at a critical moment with around 30,000 refugees and an estimated force of between 3,000 and 5,000 men. He established effective control of the region by September. The role of Zangezur was crucial because it was a connection point between Turkey and Azerbaijan. Under Andranik, the region became one of the last centers of Armenian resistance after the Treaty of Batum.[71]

Andranik's irregulars remained in Zangezur surrounded by Muslim villages that controlled the key routes connecting the different parts of Zangezur.[71] According to Donald Bloxham, Andranik initiated the change of Zangezur into a solidly Armenian land by destroying Muslim villages and trying to ethnically homogenize key areas of the Armenian state.[75] In late 1918, Azerbaijan accused Andranik of killing innocent Azerbaijani peasants in Zangezur and demanded that he withdraw Armenian units from the area. Antranig Chalabian wrote that, "Without the presence of General Andranik and his Special Striking Division, what is now the Zangezur district of Armenia would be part of Azerbaijan today. Without General Andranik and his men, only a miracle could have saved the sixty thousand Armenian inhabitants of the Zangezur district from complete annihilation by the Turko-Tatar forces in the fall of 1918";[76] he further stated that Andranik "did not massacre peaceful Tatars."[77] Andranik's activities in Zangezur were protested by Ottoman general Halil Pasha, who threatened the Dashnak government with retaliation for Andranik's actions against the Muslim civilians. Armenia's Prime Minister Hovhannes Katchaznouni said he had no control over Andranik and his forces.[78]

Karabakh

editThe Ottoman Empire was officially defeated in the First World War and the Armistice of Mudros was signed on 30 October 1918. The Ottoman forces evacuated Karabakh in November 1918 and by the end of October of that year, Andranik's forces were concentrated between Zangezur and Karabakh. Before moving towards Karabakh, Andranik made sure that the local Armenians would support him in fighting the Azerbaijanis. In mid-November 1918, he received letters from Karabakh Armenian officials asking him to postpone the offensive for 10 days to allow negotiations with the Muslims of the region. According to Hovannisian, "the time lost proved crucial." In late November, Andranik's forces headed towards Shushi—the main city of Karabakh and a major Armenian cultural center. After an intense fight against the local Kurds, his forces broke through Abdallyar (Lachin) and the surrounding villages.[79]

By early December, Andranik was 40 km (25 miles) away from Shushi when he received a message from British General W. M. Thomson in Baku, suggesting that he retreat from Karabakh because the World War was over and any further Armenian military activity would adversely affect the solution of the Armenian question, which was soon to be considered by the 1919 peace conference in Paris.[80] Trusting the British, Andranik returned to Zangezur.[81]

The region was left under limited control of the Armenian Karabakh Council. The British mission under command of Thomson arrived in Karabakh in December 1918. Thomson insisted the council "act only in local, nonpolitical matters," which sparked discontent among the Armenians.[80] An "ardent pan-Turkist" Khosrov bey Sultanov was soon appointed the governor of Karabakh and Zangezur by Thomson to "squash any unrest in the region."[81] Christopher J. Walker wrote that "[Karabakh] with its large Armenian majority remained Azerbaijani throughout the pre-Soviet and Soviet period" because of "Andranik's trust of the word of a British officer."[82]

Departure

editDuring the winter of 1918–19, Zangezur was isolated from Karabakh and Yerevan by snow. The refugees intensified the famine and epidemic conditions and gave way to inflation. In December 1918, Andranik withdrew from Karabakh to Goris. On his way, he met with British officers who suggested the Armenian units stay in Zangezur for the winter. Andranik agreed to such a proposal and on 23 December 1918, a group of Armenian leaders met in a conference and concluded that Zangezur could not cope with the influx of refugees until spring.[83] They agreed that the first logical step in relieving the tension was the reparation of more than 15,000 refugees from Nakhichevan—the adjoining district that had been evacuated by the Ottoman armies.[84] Andranik and the conference called upon the British to provide for the refugees in the interim. Major W. D. Gibbon arrived with limited supplies and money donated by the Armenians of Baku, but this was not enough to support the refugees.[85]

At the end of February 1919, Andranik was ready to leave Zangezur. Gibbon suggested Andranik and his soldiers leave by Baku-Tiflis railway at Yevlakh station. Andranik rejected this plan and on 22 March 1919, he left Goris and traveled across Sisian through deep snowdrifts to Daralagyaz, then moved to the Ararat plain with his few thousand irregulars.[84] After a three-week march, his men and horses reached the railway station of Davalu. He was met by Dro, the Assistant Minister of Military Affairs and Sargis Manasian, the Assistant Minister of Internal Affairs, who offered to take him to visit Yerevan, but he rejected their invitation as he believed the Dashnak government had betrayed the Armenians and was responsible for the loss of his homeland and the annihilation of his people. Zangezur became more vulnerable to Azerbaijani threats after Andranik left the district. Earlier, before Andranik's and his soldiers' dismissal, the local Armenian forces had requested support from Yerevan.[85]

On 13 April 1919, Andranik reached Etchmiadzin, the seat of Catholicos of All Armenians and the religious center of the Armenians, who helped the troops prepare for disbanding.[86] His 5,000-strong division had dwindled to 1,350 soldiers.[87] As a result of Andranik's disagreements with the Dashnak government and the diplomatic machinations of the British in the Caucasus, Andranik disbanded his division and handed his belongings and weapons to the Catholicos George V.[88] On 27 April 1919, he left Etchmiadzin accompanied by 15 officers, and went to Tiflis on a special train; according to Blackwood, "news of his journey traveled before him. At every station crowds were waiting to get a glimpse of their national hero."[86] He left Armenia for the last time; in Tiflis he met with Georgia's Foreign Minister Evgeni Gegechkori and discussed the Georgian–Armenian War. The Tbilisi-based writer Hovhannes Tumanyan served as their interpreter.[88]

Last years

editFrom 1919 to 1922, Andranik traveled around Europe and the United States seeking support for the Armenian refugees. He visited Paris and London, where he tried to persuade the Allied powers to occupy Turkish Armenia.[17] In 1919, during his visit to France, Andranik was bestowed the title of Legion of Honor Officier by President Raymond Poincaré.[89][90] In late 1919, Andranik led a delegation to the United States to lobby its support for a mandate for Armenia and fund-raising for the Armenian army.[17][91][92] He was accompanied by General Jaques Bagratuni and Hovhannes Katchaznouni.[93] In Fresno, he directed a campaign which raised US$500,000 for the relief of Armenian war refugees.[94]

When he returned to Europe, Andranik married Nevarte Kurkjian in Paris on 15 May 1922; Boghos Nubar was their best man.[95] Andranik and Nevarte moved to the United States and settled in Fresno, California in 1922.[96] In his 1936 short story, Antranik of Armenia, Armenian-American writer William Saroyan described Andranik's arrival. He wrote, "It looked as if all Armenians of California were at the Southern Pacific depot at the day he arrived." He said Andranik "was a man of about fifty in a neat Armenians suit of clothes. He was a little under six feet tall, very solid and very strong. He had an old-style Armenian mustache that was white. The expression of his face was both ferocious and kind."[97] Andranik lived with the family of Armen Alchian, who later became a prominent economist, in Fresno for several months.[98]

In his novel Call of the Plowmen («Ռանչպարների կանչը», 1979), where Andranik is called Shapinand, Khachik Dashtents describes his life in Fresno:

After clashing with the leaders of the Araratian Republic and leaving Armenia, Shapinand settled in the city of Fresno, California. The basement of his house was converted into a hotel. His sword, the Mosin–Nagant rifle and his military uniform hung from the wall. This is also where he kept his horse, which he had brought to America on a steamship. Those weapons, that uniform, the grey papakhi, the black boots, and lion-like steed – this was the personal wealth he had come to possess throughout his life. His business no longer had to do with weapons. Shapinand spent his free time making small wooden chairs in his hotel. Many people, refusing to buy the quality American armchairs, bought his simple ones, some for use, others as souvenirs.[99]

Death

editIn February 1926, Andranik left Fresno to reside in San Francisco in an unsuccessful attempt to regain his health.[94] According to his death certificate found in the Butte County, California records, Andranik died from angina on 31 August 1927 at Richardson Springs, California.[100][101] On 7 September 1927, citywide public attention was accorded to him for his funeral in the Ararat Cemetery, Fresno.[102] On October 9 more than 2,500 members of the Armenian community attended memorial services at Carnegie Hall in New York.[103]

He was initially buried at Ararat Cemetery in Fresno. After his first funeral, it was planned to take Andranik's remains to Armenia for final burial; however, when they arrived in France, the Soviet authorities refused permission to allow his remains to enter Soviet Armenia.[6][17] Instead they remained in France and, after a second funeral service held in the Armenian Church of Paris, were buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris on 29 January 1928.[104][105] In early 2000, the Armenian and French governments arranged the transfer of Andranik's body from Paris to Yerevan. Asbarez wrote that the transfer was initiated by Armenia's Prime Minister Vazgen Sargsyan.[106] Andranik's body was moved to Armenia on 17 February 2000.[107] It was placed in the Sport & Concert Complex in Yerevan for two days and was then taken to Etchmiadzin Cathedral, where Karekin II officiated the funeral service.[106] Andranik was re-interred at Yerablur military cemetery in Yerevan on 20 February 2000, next to Vazgen Sargsyan.[106][108][109] In his speech during the reburial ceremony, Armenia's President Robert Kocharyan described Andranik as "one of the greatest sons of the Armenian nation."[110] Prime Minister Aram Sargsyan, Foreign Minister Vartan Oskanian, and one of Andranik's soldiers, 102-year-old Grigor Ghazarian, were also in attendance.[111] A memorial was built on his grave with the phrase Zoravar Hayots—"General of the Armenians"—engraved on it.

Legacy and recognition

editPublic image

edit"General Andranik, the great Armenian leader, who is our national hero [...] For many years General Andranik kept alive the courage of all Armenians. He promised them freedom and constantly endangered his life to keep up the spirits of my people."

—Aurora Mardiganian, Ravished Armenia (1918)[112]

Andranik was considered a hero during his lifetime.[113][114] The Literary Digest described Andranik in 1920 as "the Armenian's Robin Hood, Garibaldi, and Washington, all in one."[115] The Independent wrote that he is "worshiped by his countrymen for his heroic fighting in their defense against the Turks."[116] Andranik was praised by the noted Armenian writer Hovhannes Tumanyan,[59] while Armenian Bolshevik Anastas Mikoyan wrote in his memoirs that "the name Andranik was surrounded by halo of glory."[117] Gerard Libaridian described Andranik as the "most famous of the Armenian guerrilla fighters, although not necessarily the most important. He represented the emerging new image of the Armenian who could fight."[118]

Andranik is considered a national hero among Armenians worldwide.[108][119][120] He is also seen as a legendary figure in Armenian culture.[11][121] In a series of polls in Armenia from 2006 to 2008, Andranik consistently placed second after Vazgen Sargsyan in the list of Armenian national heroes and leaders.[122]

During the Soviet period, his legacy and those of other Armenian national heroes were diminished and "any reference to them would be dangerous since they represented the strive for independence," especially prior to the Khrushchev Thaw.[123] Paruyr Sevak, a prominent Soviet Armenian author, wrote an essay about Andranik in 1963 after reading one of his soldier's notes. Sevak wrote that his generation knew "little about Andranik, almost nothing." He continued, "knowing nothing about Andranik means to know nothing about modern Armenian history."[124] In 1965, Andranik's 100th anniversary was celebrated in Soviet Armenia.[11]

Criticism

editAndranik's activities have attracted occasional criticism. He has generally been seen as a pro-Russian (and pro-Soviet) figure;[125][69] prompting the scholar-turned-political activist Rafael Ishkhanyan to criticize his for constant reliance on Russia.[126] Ishkhanyan characterized Andranik and Hakob Zavriev as leaders of the stream within Armenian political thought unconditionally reliant on Russia. He contrasted them with Aram Manukian and his self-reliant stance.[126] The poet Ruben Angaladyan voiced his opposition to the erection of a statue of Andranik in Yerevan, arguing that he does not deserve one in the national capital because he did not contribute substantially to the First Republic and ultimately left Armenia. While Angaladyan acknowledges Andranik as a popular hero, he considers it inappropriate to call him a national hero.[127]

Memorials

editStatues and memorials of Andranik have been erected around the world, including in Bucharest, Romania (1936),[128] Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris (1945), Melkonian Educational Institute, Nicosia, Cyprus (1990),[129] Le Plessis-Robinson, Paris (2005),[130][131] Varna, Bulgaria (2011),[132] and Armavir, Russia.[133][134] A memorial exists in Richardson Springs, California, where Andranik died.[135] In May 2011, a statue of Andranik was erected in Volonka village near Sochi, Russia;[136] however, it was removed the same day, apparently under pressure from Turkey, which earlier announced that they would boycott the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics if the statue remained standing.[137][138]

The first statue of Andranik in Armenia was erected in 1967 in the village of Ujan.[139][140] Another early statue in Armenia was erected in Voskehask, near Gyumri, in 1969.[141] More statues have been erected after Armenia's independence from the Soviet Union in 1991; three of which can be found in the Armenian capital of Yerevan—in Malatia-Sebastia district (2000); near the St. Gregory Cathedral (by Ara Shiraz, 2002); and outside the Fedayi Movement Museum (2006) in the Armenian capital Yerevan.[142] Elsewhere in Armenia, Andranik's statues stand in Voskevan and Navur villages of Tavush, in Gyumri's Victory Park (1994), Arteni, and Angeghakot, among other places.[143][144][145][146]

Numerous streets and squares both inside and outside Armenia, including in Córdoba, Argentina,[147] Plovdiv[148] and Varna[149] in Bulgaria, Meudon, Paris[150][151] and a section of Connecticut Route 314 state highway running entirely within Wethersfield, Connecticut[152] are named after Andranik. General Andranik Station of the Yerevan Metro was opened in 1989 as Hoktemberyan Station and was renamed for Andranik in 1992.[2][153] In 1995, General Andranik's Museum was founded in Komitas Park of Yerevan, but was soon closed because the building was privatized.[154] It was reopened on 16 September 2006, by Ilyich Beglarian as the Museum of Armenian Fedayi Movement, named after Andranik.[155]

According to Patrick Wilson, during the First Nagorno-Karabakh War Andranik "inspired a new generation of Armenians."[156] A volunteer regiment from Masis named "General Andranik" operated in Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh during the conflict.[157]

Many organizations and groups in the Armenian diaspora are named after Andranik.[158][159][160][161] On 11 September 2012, during the Bulgaria vs. Armenia football match in Sofia's Levski National Stadium, Armenian fans brought a giant poster with pictures of General Andranik and Armenian officer Gurgen Margaryan, who was murdered in 2004 by Azerbaijani lieutenant Ramil Safarov. The text on the poster read, "Andranik's children are also heroes ... The work will be done."[162] In the Armenian Youth Federation Eastern Region, the Granite City chapter is named "Antranig" in Andranik's honor.

The 65 page manuscripts of General Andranik, the only known memoir written by him, were returned to Armenia in May 2014 and sent to the History Museum of Armenia through Culture Minister Hasmik Poghosyan, almost a century after Andranik had parted with them.[163]

In culture

editAndranik has been figured prominently in the Armenian literature, sometimes as a fictional character.[121] The Western Armenian writer Siamanto wrote a poem entitled "Andranik", which was published in Geneva in 1905.[164] The first book about Andranik was published during his lifetime. In 1920, Vahan Totovents, under the pen name Arsen Marmarian, published the book Gen. Andranik and His Wars (Զոր. Անդրանիկ և իր պատերազմները) in Entente-occupied Constantinople.[121] The famed Armenian-American writer William Saroyan wrote a short story titled Antranik of Armenia, which was included in his collection of short stories Inhale and Exhale (1936).[165] Another US-based Armenian writer Hamastegh's novel The White Horseman (Սպիտակ Ձիավորը, 1952) was based on Andranik and other fedayi.[166][167] Hovhannes Shiraz, one of the most prominent Armenian poets of the 20th century, wrote at least two poems about Andranik; one in 1963 and another in 1967. The latter one, titled Statue to Andranik (Արձան Անդրանիկին), was published in 1991 after Shiraz's death.[168] Sero Khanzadyan's novel Andranik was suppressed for years and was published in 1989 when the tight Soviet control over publications was relaxed.[169][170] Between the 1960s and the 1980s, author Suren Sahakyan collected folk stories and completed a novel, "Story about Andranik" (Ասք Անդրանիկի մասին). It was first published in Yerevan in 2008.[171]

Andranik's name has been memorialized in numerous songs.[31] In 1913, Leon Trotsky described Andranik as "a hero of song and legend."[16] Italian diplomat and historian Luigi Villari wrote in 1906 that he met a priest from Turkish Armenia in Erivan who "sang the war-song of Antranik, the leader of Armenian revolutionary bands in Turkey."[172] Andranik is one of the main figures featured in Armenian patriotic songs, performed by Nersik Ispiryan, Harout Pamboukjian and others. There are dozens of songs dedicated to him, including Like an Eagle by gusan Sheram, 1904[173] and Andranik pasha by gusan Hayrik.[174] Andranik also features in the popular song The Bravehearts of the Caucasus (Կովկասի քաջեր) and other pieces of Armenian patriotic folklore.[175]

Several documentaries about Andranik have been produced; these include Andranik (1929) by Armena-Film in France, directed by Asho Shakhatuni, who also played the main role;[176][177] General Andranik (1990) directed by Levon Mkrtchyan, narrated by Khoren Abrahamyan; and Andranik Ozanian, a 53-minute-long documentary by the Public Television of Armenia.[178]

Awards

editThrough his military career, Andranik was awarded with a number of medals and orders by governments of four countries.[179] Andranik's medals and sword were moved to Armenia and given to the History Museum of Armenia in 2006.[180][181]

| Country | Award | Rank | Year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kingdom of Bulgaria | Order of Bravery | IV grade,

"For Bravery" |

1913[182][50] | |

| Russian Empire | Order of St. Stanislaus | II class

with Swords |

1914–16[183] | |

| Order of St. Vladimir | IV class

|

1914–16[183][184] | ||

| Cross of St. George | I, II, III class

|

1914–16[49][183] | ||

| Order of St. George | II, III, IV classes

|

1914–16[185][183] | ||

| French Republic | Legion of Honor | Officier

|

1919[115] | |

| Kingdom of Greece | War Cross | II class

|

1920[186][187] |

Published works

edit- Մարտական հրահանգներ: Առաջարկներ, նկատողութիւններ եւ խորհուրդներ [Combat Commands: Suggestions, Remarks, Recommendations]. Geneva: ARF Press. 1906. OCLC 320038626.[40]

- Հայկական առանձին հարուածող զօրամասը [The Armenian Special Striking Division]. Boston: Azg. 1921. OCLC 49525413.[188]

- Զորավար Անդրանիկը կը խոսի [General Andranik Speaks]. Paris: Abaka weekly. 1921. OCLC 234085160.

- Առաքելոց վանքին կռիւը (Հայ յեղափոխութենէն դրուագ մը) [The Battle of Arakelots (An Episode of Armenian Revolution)]. Boston: Baikar. 1924. Memoirs of Andranik written down by Levon K. Lyulejian.[189]

References

edit- Notes

- ^ Andranik was given the rank of a major-general by the command of the Caucasus Front, a formation of the army of the dissolved Russian Republic.[3]

- ^ In classical orthography his name is spelled Անդրանիկ Օզանեան and pronounced [ɑntʰɾɑniɡ ɔzɑnjɑn] in Western Armenian. In reformed orthography his name is spelled Անդրանիկ Օզանյան and pronounced [ɑndɾɑnik ɔzɑnjɑn] in Eastern Armenian.

- ^ Զօրավար Անդրանիկ in classical spelling, Զորավար Անդրանիկ in reformed, Zoravar Andranik.

- ^ Armenian: Անդրանիկ. Also spelled Antranik or Antranig

- ^ Some sources mistakenly indicate 1866 as Andranik's date of birth.[5] 1866 is also engraved on his grave in the Père Lachaise Cemetery. Some sources also erroneously indicate 1928 as his date of death, perhaps because Andranik's body was moved to France and reburied there in 1928.[6]

- Citations

- ^ a b Libaridian, Gerard J. (1991). Armenia at the Crossroads: Democracy and Nationhood in the Post-Soviet Era. Watertown, Massachusetts: Blue Crane Books. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-9628715-1-1.

- ^ a b Holding, Nicholas (2008). Armenia, with Nagorno Karabagh (2nd ed.). Chalfont St. Peter: Bradt Travel Guides. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-84162-163-0.

- ^ a b Hovannisian, Richard G. (1967). Armenia on the Road to Independence, 1918. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-520-00574-7.

- ^ a b Adalian 2010, p. 79.

- ^ a b Hovannisian, Richard G. (2000). Armenian Van/Vaspurakan. Costa Mesa, California: Mazda Publishers. p. 233. ISBN 978-1-56859-130-8.

- ^ a b Hovannisian 1971, p. 191.

- ^ Sarkisyanz, Manuel (1975). A Modern History of Transcaucasian Armenia: Social, Cultural, and Political. Leiden, Netherlands: E.J. Brill. p. 140. OCLC 8305411.

- ^ a b c d e f g Walker 1990, p. 178.

- ^ Panossian, Razmik (2006). The Armenians: From Kings and Priests to Merchants and Commissars. London: Columbia University Press. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-231-51133-9.

- ^ Ghaziyan, Alvard (1984). Զորավար Անդրանիկը որպես վիպա-հերոսական կերպար [General Andranik as a heroic character] (in Armenian). Yerevan: Institute of Archeology and Ethnography, Armenian National Academy of Sciences. pp. 25–26. Archived from the original on 20 December 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Haroutyunian, A. (1974). "Անդրանիկ [Andranik]". In Hambardzumyan, Viktor (ed.). Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia (in Armenian). Vol. 1. Yerevan: Armenian Encyclopedia Publishing. p. 392.

- ^ a b c Chalabian 1988, p. 3.

- ^ Aghayan 1968, p. 40.

- ^ Nalbandian, Louise (1963). The Armenian Revolutionary Movement: The Development of Armenian Political Parties Through the Nineteenth Century. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-520-00914-1.

- ^ a b c d Aghayan 1968, p. 41.

- ^ a b c Trotsky 1980, p. 247.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Walker 1990, p. 411.

- ^ Mouradian 1995, p. 12.

- ^ Haroutyunian 1965, p. 109.

- ^ a b c d Trotsky 1980, p. 249.

- ^ Akçam, Taner (2006). A shameful act: the Armenian genocide and the question of Turkish responsibility. New York: Metropolitan Books. p. 42. ISBN 0-8050-7932-7.

- ^ a b c New Armenia 1920, p. 82.

- ^ Mouradian 1995, p. 103.

- ^ Vardanian, Mikayel (1931). Մուրատ (Սեբաստացի ռազմիկին կյանքն ու գործը) [Murad (The Sebastatsi Fighter's Life and Case] (in Armenian). Boston: Hairenik Association. p. 96.

- ^ "Treaty between Great Britain, Germany, Austria, France, Italy, Russia, and Turkey for the Settlement of Affairs in the East: Signed at Berlin, July 13, 1878", American Journal of International Law Volume II, 1908, p. 422

- ^ a b Walker 1990, p. 177.

- ^ Ternon, Yves (1990). The Armenians: history of a genocide (2nd ed.). Delmar, New York: Caravan Books. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-88206-508-3.

- ^ Trotsky 1980, pp. 249–250.

- ^ a b Kharatian 1990, p. 8.

- ^ a b Chalabian, Antranig (June 1995). "Bold and fiercely determined, Andranik Ozanian spent most of his life as a revolutionary for his fellow Armenians". Military History Monthly. 12 (2): 10.

- ^ a b New Armenia 1920, p. 83.

- ^ Hambarian 1989, p. 22.

- ^ a b Chalabian 2009, p. 17.

- ^ a b Hambarian 1989, p. 24.

- ^ a b c d e f g Trotsky 1980, p. 250.

- ^ Hambarian 1989, p. 26.

- ^ Mouradian 1995, p. 88.

- ^ a b c Hambarian 1989, p. 31.

- ^ a b c d e New Armenia 1920, p. 84.

- ^ a b "1906" (in Armenian). National Library of Armenia. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- ^ Chalabian 1988, p. 170.

- ^ Kharatian 1990, p. 10.

- ^ Aghayan 1968, p. 42.

- ^ Trotsky 1980, p. 251.

- ^ Trotsky 1980, p. 252.

- ^ Trotsky 1980, p. 253.

- ^ Walker 1990, p. 194.

- ^ Chalabian 1988, p. 202.

- ^ a b c d e Aghayan 1968, p. 43.

- ^ a b Chalabian 1988, p. 203.

- ^ Kharatian 1990, p. 11.

- ^ Chalabian 2009, p. 45.

- ^ a b c Payaslian 2007, p. 136.

- ^ Marie-Aude Baronian; Stephan Besser; Yolande Jansen (2007). Diaspora and Memory: Figures of Displacement in Contemporary Literature, Arts and Politics. Rodopi. p. 174. ISBN 978-90-420-2129-7.

- ^ Shirinian, Lorne (1992). The Republic of Armenia and the rethinking of the North-American Diaspora in literature. E. Mellen Press. p. ix. ISBN 978-0-7734-9613-2.

- ^ a b Hovannisian 1971, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d e f Aghayan 1968, p. 44.

- ^ a b Chalabian 2009, p. 52.

- ^ a b c d Aghayan 1968, p. 45.

- ^ Hovannisian 1971, pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b c Hovannisian 1971, p. 15.

- ^ Nichanian, Marc (2002). Writers of Disaster: Armenian Literature in the Twentieth Century. Vol. 1. Princeton, New Jersey: Gomidas Institute. p. 236. ISBN 978-1-903656-09-9.

- ^ Kharatian 1990, p. 12.

- ^ Hovannisian 1971, p. 20.

- ^ Hovannisian 1971, p. 21.

- ^ a b c Walker 1990, p. 250.

- ^ Hovannisian 1971, p. 22.

- ^ a b Hovannisian 1971, p. 24.

- ^ a b c d Aghayan 1968, p. 46.

- ^ Walker 1990, p. 256.

- ^ a b c d e Hovannisian 1971, p. 87.

- ^ Walker 1990, p. 272-273.

- ^ Aghayan 1968, p. 47.

- ^ Hovannisian 1971, p. 86.

- ^ Bloxham, Donald (2005). The Great Game of Genocide: Imperialism, Nationalism, and the Destruction. Oxford University Press. pp. 103–105. ISBN 978-0-19-927356-0.

- ^ Chalabian 2009, p. 409.

- ^ Chalabian 2009, p. 545.

- ^ Hovannisian 1971, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Hovannisian 1971, pp. 88–89.

- ^ a b Hovannisian 1971, p. 89-90.

- ^ a b Walker 1990, p. 270.

- ^ Walker 1990, pp. 270–272.

- ^ Hovannisian 1971, p. 189.

- ^ a b Hovannisian 1971, p. 190.

- ^ a b Hovannisian 1971, p. 193.

- ^ a b Blackwood's 1919, p. 476.

- ^ Chalabian 2009, p. 119.

- ^ a b Chalabian 2009, pp. 119–120.

- ^ The Armenian Review, Hairenik Association, 1976, p. 239

- ^ Macler, Frédéric. Revue des Études Arméniennes (in French). Paris: Imprimerie nationale, 1920, p. 158

- ^ "Armenia's National Hero Pleads His Country's Cause in America". The Literary Digest. 20 December 1919. p. 94. Archived from the original on 29 May 2016.

- ^ "Armenian Mandate Assailed by Gerard". The New York Times. 8 December 1919. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- ^ Chalabian 2009, p. 155.

- ^ a b The Fresno Bee, Death Claims Famous General, Once of Fresno, 31 August 1927

- ^ "General Antranig, The Armenian Leader". Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, University of Minnesota. 2009. Archived from the original on 1 July 2010.

- ^ Aghayan 1968, p. 22.

- ^ Saroyan, William (1943). 31 selected stories from "Inhale and Exhale". New York: Avon Book Company. p. 107.

- ^ ""The Armenian Adam Smith": UCLA Holds Conference in Honor of Armenian Economist". Asbarez. 26 May 2006. Archived from the original on 7 September 2022.

- ^ Dashtents, Khachik (1979). "Կարոտ [Nostalgia]". Ռանչպարների կանչը [Call of Plowmen] (in Armenian). Yerevan: Sovetakan grogh. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012.

- ^ Demirjian, Nubar (27 August 2010). "Զօրավար Անդրանիկի Մահուան 83րդ Ամեակի Առիթով [On the 83rd anniversary of General Andranik's death]". Asbarez. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ "General Antranik, Noted Fight Dies". The New York Times. 2 September 1927. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ Avakian, Arra S. (1998). Armenia: A Journey Through History. Electric Press. pp. 311–314. ISBN 978-0-916919-20-7.

- ^ "Armenians Eulogize General Andranik; Speakers at Memorial Meeting Mourn Him as Greatest Hero of Native Land". The New York Times. 10 October 1927. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- ^ Chalabian 1988, p. 541.

- ^ Aghayan 1968, p. 52.

- ^ a b c "Gen. Andranik's Remains to Be Buried in Armenia". Asbarez. 9 February 2000. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- ^ "Armenian Community in France Bids Farewell to Gen. Andranik's Remains". Asbarez. 17 February 2000. Archived from the original on 3 October 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- ^ a b Adalian 2010, p. ixv.

- ^ Khanbabyan, Armen (22 February 2000). Перезахоронен прах героя [The remains of the hero were reburied]. Nezavisimaya Gazeta (in Russian). Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ Kocharyan, Robert (20 February 2000). "Խոսքը Անդրանիկ Զորավարի աճյունի վերաթաղման արարողության ժամանակ [Speech at the reburial ceremony of General Andranik]". Office to the President of the Republic of Armenia. Archived from the original on 27 August 2007. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- ^ "Andranik Pasha". JanFedayi.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ Mardiganian, Aurora (1918). Ravished Armenia. New York: Kingfield Press. pp. 249–250.

- ^ Hovannisian, Richard G. (2002). Armenian Tsopk/Kharpert. Costa Mesa, California: Mazda Publishing. p. 430. ISBN 978-1-56859-150-6.

- ^ Albert, Shaw, ed. (July–December 1919). "Armenia's Military Hero". The American Review of Reviews. LX (60). New York: 640–641.

- ^ a b Wheeler, Edward Jewitt; Funk, Isaac Kaufman; Woods, William Seaver; Draper, Arthur Stimson; Funk, Wilfred John (17 January 1920). "General Andranik, the Armenian Washington". The Literary Digest. Vol. 64. pp. 90–92. Archived from the original on 17 May 2016.

- ^ Bacon, Leonard; Thompson, Joseph Parrish; Storrs, Richard Salter; Leavitt, Joshua; Beecher, Henry Ward; Bowen, Henry Chandler; Tilton, Theodore; Ward, William Hayes; Holt, Hamilton; Franklin, Fabian; Fuller, Harold de Wolf; Herter, Christian Archibald (27 March 1920). "We Are Desperate! A First-hand Story of the Present Situation in the Near East By General Antranik The Armenian Leader". The Independent. pp. 467–468. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016.

- ^ Simonian 1988, p. 12.

- ^ Libaridian, Gerard, ed. (1991). Armenia at the Crossroads: Democracy and Nationhood in the Post-Soviet Era. Watertown, MA: Blue Crane. p. 20.

- ^ Peterson, Merrill D. (2004). "Starving Armenians": America and the Armenian genocide, 1915–1930 and After. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-8139-2267-6.

- ^ Dadrian, Vahakn N. (2004). Warrant for Genocide: Key Elements of Turko-Armenian Conflict. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-4128-4119-1.

- ^ a b c Kharatian 1990, p. 3.

- ^ surveys:

- "Armenia National Voter Study November 2006" (PDF). IRI, USAID, Baltic Surveys Ltd./The Gallup Organization, ASA. p. 46. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- "Armenia National Voter Study March 16-25, 2007" (PDF). IRI, USAID, Baltic Surveys Ltd./The Gallup Organization, ASA. p. 57. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- "Armenia National Voter Study July 2007" (PDF). IRI, USAID, Baltic Surveys Ltd./The Gallup Organization, ASA. p. 55. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- "Armenia National Voter Study October 27 – November 3, 2007" (PDF). IRI, USAID, Baltic Surveys Ltd./The Gallup Organization, ASA. p. 60. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- "Armenia National Voter Study January 13 – 20, 2008" (PDF). IRI, USAID, Baltic Surveys Ltd./The Gallup Organization, ASA. p. 49. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ^ Harutyunyan, Angela; Hörschelmann, Kathrin; Miles, Malcolm (2009). Public spheres after socialism. Bristol, UK: Intellect Books. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-84150-212-0.

- ^ "Պարույր Սեւակը՝ Անդրանիկի մասին [Paruyr Sevak about Andranik]". Report.am (in Armenian). 25 February 2012. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ Suny, Ronald G. (1993). Looking toward Ararat: Armenia in modern history. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-253-20773-9.

- ^ a b First published in English in Ishkhanian, Rafael (1991). "The Law of Excluding the Third Force". In Libaridian, Gerard (ed.). Armenia at the Crossroads: Democracy and Nationhood in the Post-Soviet Era. Watertown, MA: Blue Crane. pp. 20–21.

- ^ Avagyan, Lilit (23 July 2013). Մայրաքաղաքում Անդրանիկի արձան չպիտի լիներ. 168hours (in Armenian). Archived from the original on 21 September 2013.

- ^ Zhamgochyan, Eduard (19 February 2012). "Собор, община, люди [Cathedral, community and people]". Aniv (in Russian). 5 (38). Archived from the original on 24 June 2014.

- ^ A bust of Andranik at the Melkonian school in Nicosia

- ^ "Ֆրանսիայի Պլեսի-Ռոբենսոն քաղաքում բացվել է զորավար Անդրանիկի արձանը [General Andranik's state opened in France's Le Plessis-Robinson]" (in Armenian). Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 7 June 2005. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ "Jumelage avec Arapkir" (in French). City Hall of Plessis Robinson. 26 April 2006. Archived from the original on 24 June 2014. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

Square des Martyrs, s'élève le buste d'un des grands libérateurs de l'Arménie, le général Andranik.

- ^ "Откриха паметник на генерал Андраник" (in Bulgarian). SKAT. 8 July 2011. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ Через год после демонтажа памятника Андранику, на Кубани открыта мемориальная доска памяти Андраника и Нжде. Yerkramas (in Russian). 29 May 2012. Archived from the original on 25 October 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ "Ռուսական Արմավիրում Անդրանիկ Օզանյանի և Գարեգին Նժդեհի պատվին հուշատախտակ է բացվել". News.am. 29 May 2012. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ Mitchell, Larry (31 August 2012). "Memorial marks Armenian hero's death at hotel north of Chico". Chicoer. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ^ В Лазаревском районе Сочи установлен памятник генералу Андранику Озаняну. Yerkramas (in Russian). 28 May 2011. Archived from the original on 3 July 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ "Community Ordered to Take Down Gen. Antranig Statue in Sochi". Asbarez. 1 June 2011. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ Памятник генералу Андранику в Сочи снесен. Yerkramas (in Russian). 28 May 2011. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ Zoryan, Satenik (26 February 2010). "Անպարտելի զորավարը [The Undefeated General]". Hayastani Hanrapetutyun (in Armenian). Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ Hakobyan, Armen. "Միասնությունը մարդկանց մեջ պետք է լինի [Unity should be in the people]". Hayots Ashkhar (in Armenian). Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ Government of Armenia. "Շիրակի մարզի պատմության և մշակույթի անշարժ հուշարձանների պետական ցուցակ". arlis.am (in Armenian). Armenian Legal Information System. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021.

Ոսկեհասկ գյուղ ՀՈՒՇԱՐՁԱՆ' ԱՆԴՐԱՆԻԿ ԶՈՐԱՎԱՐԻՆ 1969 թ. գյուղի մեջ, մշակույթի տան մոտ

- ^ "Երևանի հուշարձանները [Statues of Yerevan]" (in Armenian). Yerevan Municipality Official Website. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- ^ "Թիմը գնում է գյուղեր. այսօր' Նավուր [Straight to Navur]". CivilNet. 11 October 2011. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ "Գյումրի [Gyumri]". Great School Encyclopedia, Volume II (in Armenian). Armenian Encyclopedia Publishing. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ^ "Անցումային շրջան [A transitional period]". Aravot (in Armenian). 30 July 2011. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ^ "Հայի ուժը N-80 Անգեղակոթ". Yerkir Media. 23 June 2013. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- ^ "Pje Antranick Córdoba, Argentina". Google Maps. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ "ulitsa "Antranik" 4000 Plovdiv, Bulgaria". Google Maps. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ Savov, Nikolai (27 November 2011). "Големият, нов паметник на генерал Андраник [А new monument to General Andranik]" (in Bulgarian). Urban-mag. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ Keshishian, Petros (9 November 2008). "Andranik square in Meudon". Azg Daily. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ "Rue du Général Antranik 92190 Meudon, France". Google Maps. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ "Highway Log Connecticut State Numbered Routes and Roads" (PDF). Connecticut Department of Transportation. 31 December 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ "Станция "Зоравар Андраник" ["Zoravar Andranik" Station]" (in Russian). Metroworld. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ "Zoravar Andranik's Museum To Re-open in Yerevan on 27 May". Aravot. 19 May 2006. Archived from the original on 19 September 2013. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- ^ "Զորավարի պատգամին հավատարիմ [Faithful to General's commandment]" (in Armenian). A1plus. 20 August 2006. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ Gore, Patrick Wilson (2008). 'Tis Some Poor Fellow's Skull: Post-Soviet Warfare in the Southern Caucasus. iUniverse. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-595-60775-4.

- ^ Arakelyan, Serzh (12–19 January 2011). "Հրեղեն ոգու կանչը [Call of the fiery spirit]" (in Armenian). Hay Zinvor # (806), the Defense Ministry of Armenia. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- ^ "Chapters". Armenian Youth Federation. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ "Homenetmen". Hayk the Ubiquitous Armenian. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ "The Antranig Dance Ensemble". Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ "Grupo Scout General Antranik" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 8 October 2018. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ "A poster with pictures of General Andranik and Gurgen Margaryan in "National" stadium of Sofia". Lurer.com. 11 September 2012. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ "General Andranik Papers Find Home in Armenia". The Armenian Mirror-Spectator. 9 May 2014. Archived from the original on 3 January 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ Siamanto (1905). Հայորդիները [Hayordinerě] (in Armenian). Geneva: Kedronakan Tparan. p. 9.

- ^ Hovannisian, Richard G. (2008). The Armenian Genocide in Perspective. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-4128-0891-0.

- ^ Hamastegh (1952). Սպիտակ Ձիավորը [White Horseman] (in Armenian). Los Angeles: Horizon. OCLC 10999057.

- ^ Khachatrian, M. M. "Համաստեղի "Սպիտակ Ձիավորը" վեպը [Hamastegh՚ s novel "The White Rider"]". Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutyunneri (in Armenian). Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences: 125–134. ISSN 0320-8117. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ^ "Շիրազի երկու ինքնագրերը [Two autographs of Shiraz]" (in Armenian). "HAYART" Literary Network. Archived from the original on 17 September 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ Khanzadyan, Sero (1989). Անդրանիկ [Andranik]. Yerevan: Khorhrdayin Grogh. OCLC 605225665.

- ^ Bardakjian, Kevork B. (2000). A Reference Guide to Modern Armenian Literature, 1500–1920: With an Introductory History. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-8143-2747-0.

- ^ "Story About General Andranik – Epic Novel Written and Developed by Suren Sahakian Published After Edited by L. Sahakian". "Ararat" Center of Strategic Research. 12 June 2008. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ^ Villari, Luigi (1906). Fire and Sword in the Caucasus. London: T. Fisher Unwin. p. 229.

- ^ Bakshian Jr., Aram (April 1993). "Andranik of Armenia". History Today. 43 (4). ISSN 0018-2753.

- ^ Aghajanian, Alfred, ed. (2009). Նոստալգիայի երգեր [Nostaligc Songs] (in Armenian). Los Angeles: IndoEuropean publishing. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-60444-046-1.

- ^ "Հայրենասիրական և ազգագրական – Կովկասի քաջեր [Patriotic and folk songs – The Bravehearts of the Caucasus]" (in Armenian). National Center of Educational Technologies. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ^ "Andranik" (PDF) (in French). Les Grands Romans Filmés. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ Bakhchinyan, Artsvi. "О нем мечтали женщины и ему завидовали мужчины. Бурная жизнь армянского актера Ашо Шахатуни [Life of Asho Shakhatuni]" (in Russian). Union of Theatre Workers of the Russian Federation. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ "Անդրաիկ Օզանյան տեսաֆիլմ [Andranik Ozanian film]" (in Armenian). Public Television of Armenia. 3 January 2012. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ "Պատմութեան Թանգարանին Յանձնուեցան Զօրավար Անդրանիկի Սուրը Եւ Շքանշանները [Andranik's sword and medals handed to the History Museum]". Asbarez (in Armenian). 30 November 2006. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- ^ "General Andranik's Sword and Medals Handed to History Museum of Armenia". Asbarez. 2 December 2006. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ^ "General Andranik's Sword and Medals Handed to History Museum af Armenia". Armenpress. 29 November 2006. Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ^ Pindikova, Galina, ed. (2006). Македоно-одринското опълчение 1912–1913 [Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Volunteer Corps 1912–1913] (PDF) (in Bulgarian). Sofia: State Military Archive of Bulgaria. p. 741. ISBN 978-954-9800-52-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d Grigoryan, Levon (ed.). "Рыцарь византизма [Byzantium Knight]". Византийское наследство [Byzantine Heritage] (in Russian). Vol. 64. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014.

- ^ "War Journal Of the Second Russian Fortress Artillery Regiment Of Erzeroum From its Formation Until the Recapture of Erzeroum by the Ottoman Army March 12th, 1918" (PDF). University of Louisville. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- ^ Mahdesian, Arshag D., ed. (1927). "General Antranik Ozanian". The New Armenia. 19–21 (X). New York: New Armenia Publishing Company: 53.

- ^ Haroutyunian 1965, p. 112.

- ^ "Министр обороны Армении передал саблю и ордена выдающегося армянского полководца Андраника Музею истории (Defense Minister of Armenia handed Andranik's sword and medals to the Museum of History)". Novosti Armenia (in Russian). 29 November 2006. Archived from the original on 24 June 2014.

- ^ "1921". National Library of Armenia. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- ^ "1924". National Library of Armenia. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

Bibliography

edit- Trotsky, Leon (1980). "Andranik and his Troop, from Kievskaya Mysl No. 197, July 19, 1913". The Balkan wars: 1912–13: the war correspondence of Leon Trotsky. New York: Monad Press. pp. 247–256. ISBN 978-0-909196-08-0.

- "Antranik". Blackwood's Magazine. CCVI (206): 441–477. October 1919.

- Mahdesian, Arshag D., ed. (June 1920). "General Antranik". The New Armenia. 12 (6). New York: New Armenia Publishing Company: 82–85.

- Haroutyunian, A. H. (1965). "Անդրանիկը որպես մարտիկ և զորավար /Ծննդյան 100-ամյակի առթիվ/ [Andranik as Warrior and Commander]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian) (1). Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences: 109–124.

- Aghayan, Tsatur (1968). "Զորավար Անդրանիկի գործունեության մասին [On the Activities of General Andranik]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian) (2). Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences: 40–56.

- Hovannisian, Richard (1971). The Republic of Armenia: Volume 1, The First Years, 1918–1919. Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-01805-2.

- Chalabian, Antranig (1988). General Andranik and the Armenian Revolutionary Movement. Southfield, Michigan: Antranig Chalabian.

- Hambarian, A. S. (1989). "Սասունի 1904 թվականի գոյամարտը [Sasun's Self-Defence in 1904]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian) (4). Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences: 22–34. ISSN 0135-0536.

- Walker, Christopher J. (1990). Armenia: The Survival of a Nation (revised second ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-04230-1.

- Kharatian, A. (1990). "Վահան Թոթովենցը Անդրանիկի մասին [Vahan Totovents about Andranik]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian) (1). Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences: 3–14. ISSN 0135-0536.

- Mouradian, George (1995). Armenian infotext. Southgate, Michigan: Bookshelf Publishers. ISBN 978-0-9634509-2-0.

- Payaslian, Simon (2007). The history of Armenia. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-7467-9.

- Chalabian, Antranig (2009). Dro (Drastamat Kanayan): Armenia's First Defense Minister of the Modern Era. Los Angeles: Indo-European Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60444-078-2.

- Adalian, Rouben Paul (2010). Historical Dictionary of Armenia. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7450-3.

Further reading

editArticles

edit- Nercissian, M.; Harutyunian, A.; Mouradian, D. (1981). "Материалы о генерале Андранике [Documents on General Andranik]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Russian) (1). Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences: 242–248. ISSN 0135-0536.

- Karapetyan, H. (1996). "Անդրանիկ (Andranik)". Հայկական հարց» հանրագիտարան ["Armenian Question" Encyclopedia] (in Armenian). Yerevan: Armenian Encyclopedia Publishing. (archived link)

- Hrachik, Simonian (2000). "Զորավար Անդրանիկ (ընդհանուր բնութագիր) [General Andranik (general characteristic)]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian) (1). Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences: 44–50. ISSN 0135-0536.

- Severikova, N. M. (2007). "Великий сын Отечества: К 80-летию со дня кончины Андраника Сасунского [Great Son of Fatherland: On the 80th anniversary of death of Andranik of Sasun]". Historical Science (in Russian) (6). Massmedia Center of the Moscow State University. ISSN 2304-4551.

Books

edit- Զօրավար Անդրանիկի կովկասեան ճակատի պատմական օրագրութիւնը 1914–1917 [Historic Timeline of Caucasian Front of General Andranik] (in Armenian). Boston: Baikar. 1924.

- Aharonyan, Vardges (1957). Անդրանիկ. մարդը եւ ռազմիկը [Andranik: the man and the soldier] (in Armenian). Boston: Hairenik. OCLC 47085812.

- Զօր. Անդրանիկ (Օզանեան) կեանքն ու գործունէութիւնը (PDF) (in Armenian). Beirut, Lebanon: Hamazkayin. 1985. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- Chalabian, Antranig (1986). Զօրավար Անդրանիկ Եւ Հայ Յեղափոխական Շարժումը [General Andranik and the Armenian Revolutionary Movement] (in Armenian). Beirut: Donikian Press.

- Simonian, Hrachik (1988). "Истинный народный герой [The True Popular Hero]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Russian) (3). Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences: 12–28. ISSN 0135-0536.

- Antranig, Chalabian (1990). Զօրավար Անդրանիկ Եւ Հայ Յեղափոխական Շարժումը [General Andranik and the Armenian Revolutionary Movement] (in Armenian). Yerevan: Ա. հ.

- Garibdzhanian, Gevorg (1990). Ժողովրդական հերոս Անդրանիկ [Andranik the Popular Hero] (in Armenian). Yerevan: Hayastan Publishing. OCLC 26596860.

- National Archives of Armenia (1991). Андраник Озанян. документы и материалы [Andranik Ozanian: documents and materials] (in Russian). Yerevan: National Archives of Armenia.

- Aghayan, Tsatur (1994). Անդրանիկ. դարաշրջան, դեպքեր, դեմքեր [Andranik: era, events, faces] (in Armenian). Yerevan: ՀԲՀ հրատ.

- Simoyan, Hrachik (1996). Անդրանիկի ժամանակը [Andranik's time] (in Armenian). Yerevan: Kaisa.

- Aghayan, Tsatur (1997). Андраник и его эпоха [Andranik and his era] (in Armenian). Moscow: Международный гуманитарный фонд арменоведения им. Ц. П. Агояна. ISBN 5-7801-0050-0.

- Grigoryan, Ashot (2002–2004). "Անդրանիկագիտական Հանդես Andranikological Review" (Document) (in Armenian). Yerevan: Ashot Grigoryan.

- Simonyan, Ruben (2006). Անդրանիկ. Սիբիրական վաշտի ոդիսականը [Andranik: The Siberian company's odyssey] (in Armenian). Yerevan: Voskan Yerevantsi. OCLC 76872489.

- Andreasyan, Vazken (1982). Անդրանիկ (PDF) (in Armenian). Beirut, Lebanon: Tonikyan.