Iwatayama Monkey Park (Japanese: 嵐山モンキーパーク, Arashiyama Monkī Pāku) is a commercial park located in Arashiyama in Kyoto, Japan. The park is located atop Mount Arashiyama, on the opposite side of the Ōi River of the train station. It is inhabited by a troop of over 120 Japanese macaque monkeys.[1] The animals are wild but can be fed by the staff and visitors with food exclusively purchased at the site.[2] The main reason why these wild macaques choose to stay in the park, is so that they can feed on the food given by the staff. The feeding system includes corn and wheat handed out every two hours from 9:30 to 5:30 (five times a day).[3]

| Iwatayama Monkey Park | |

|---|---|

| Arashiyama Monkey Park Iwatayama | |

| 嵐山モンキーパークいわたやま | |

Iwatayama Monkey Park | |

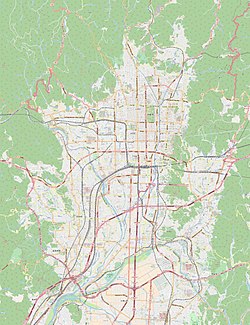

| Location | 61 Arashiyama Nakaoshitachō, Nishikyō-ku, Kyōto-shi, Kyōto-fu 616-0004, Japan |

| Nearest city | Kyoto |

| Coordinates | 35°00′32″N 135°40′29″E / 35.008938°N 135.674681°E |

| Open | 15 March-30 September, 09:00-16:30; 1 October-14 March, 09:00-16:00 |

| Habitats | bamboo forest |

| Connecting transport | Keifuku Arashiyama station, Hankyu Arashiyama station |

| Website | http://www.monkeypark.jp/ |

To visit this park, visitors have to go up a somewhat steep mountain. The climb is about 0.9 miles.[4] Visitors should be aware that the park closes at 5pm and all guests must pay a small fee to enter the park.[2]

Macaque naming

editThe macaques at Iwatayama Monkey Park roam freely, but they are well-known to the park staff. Many can be recognized just by sight. According to Nobuo Asaba, one of the park’s concessionaires, “If you really care, you have to memorize everyone’s name.” [5] Some of the macaques have even earned nicknames, like Cooper. Typically, each macaque is given a formal name based on its matriline, with the family name followed by numbers indicating the birth year of the direct female descendant.[5]

The monkey naming system was pioneered by student researcher Naonosuke Hazama.[6] In partnership with local business leaders, Hazama developed a plan in 1954 to study and acclimate the monkeys for both tourism and scientific exploration.[6] It was during this time that Hazama and his team began assigning names to individual monkeys, establishing a naming tradition that extended to their offspring. This system became the cornerstone for some of the earliest and most in-depth research on primate social structures and kinship-based networks.[6]

Park history

editThe land where the park and tourist facilities now stand, were donated by businessman, Sonosuke Iwata, whose family name is also given to the mountain it rests upon. [6] The Iwatayama Monkey Park in Arashiyama officially opened to the public in March 1957. Iwata financially supported the park's operations until 1974, when it was sold to Kyoto City due to financial difficulties, and designated a protected historical reserve. [6] In a lot of ways, this park is a family run business. More specifically, the men who ran the park, pass the duties along to their sons after they decide to retire. We see an example of this when Asaba Shinsuke succeeded his father Asaba Nobuo in running the park.[7]

Research history

editThere has been a history of research starting in 1948 at the Iwatayama Monkey Park.[6] There have been around 115 people who have either done research or advised research at the site, showcasing the impact the site has had on the research of primates. Studies have span an array of topics, including basic ecology, social behavior, endocrinology, genetics, and reproductive physiology.[6]

References

edit- ^ "嵐山モンキーパークいわたやまって?". www.monkeypark.jp. Retrieved 2020-09-02.

- ^ a b McKirdy, Euan (November 13, 2009). "Travel: One hour out: Osaka --- Arashiyama: a river runs through it". The Wall Street Journal Asia. ProQuest 315594410. Retrieved October 31, 2024.

- ^ Wolfe, Linda D; Gray, J Patrick (1982). "Japanese Monkeys and Popular Culture". Journal of Popular Culture. 16 (3): 97. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.1982.1603_97.x. ProQuest 1297347525.

- ^ Studarus, Laura. "Fancy a Visit to Arashiyama Monkey Park Iwatayama?". Wondertrunk. Retrieved 4 November 2024.

- ^ a b Craft, Lucille (March 8, 1996). "Wildlife: Meticulous Monkey-Watchers". Asian Wall Street Journal. ProQuest 315631676.

- ^ a b c d e f g Huffman, Michael (January 2012). The Monkeys of Stormy Mountain: 60 Years of Primatological Research on the Japanese Macaques of Arashiyama. Cambridge University Press. pp. 13–27.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Knight, J. (January 1, 2011). Herding Monkeys to Paradise. Brill. p. 204. ISBN 9789004203242.