Arivaca (O'odham: Ali Wa:pk) is an unincorporated community in Pima County, Arizona, United States.[2] It is located 11 miles (18 km) north of the Mexican border and 35 miles (56 km) northwest of the port of entry at Nogales. The European-American history of the area dates back at least to 1695, although the community was not founded until 1878.[2] Arivaca has the ZIP code 85601.[3] The 85601 ZIP Code Tabulation Area had a population of 909 at the 2000 census.[4]

Arivaca, Arizona | |

|---|---|

Arivaca, facing west down Main Street, 2015 | |

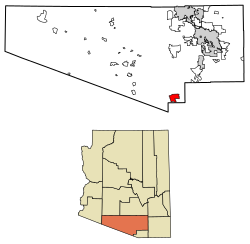

Location of Arivaca in Pima County, Arizona. | |

| Coordinates: 31°34′38″N 111°19′53″W / 31.57722°N 111.33139°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Arizona |

| County | Pima |

| Area | |

• Total | 27.78 sq mi (71.94 km2) |

| • Land | 27.78 sq mi (71.94 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 3,643 ft (1,110 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 623 |

| • Density | 22.43/sq mi (8.66/km2) |

| Time zone | MST (no DST) |

| FIPS code | 04-03320 |

History

editEarly history

editThe early history of Arivaca is obscure. It was probably a Pima or Tohono O'odham village, abandoned after the Pima Indian Revolt of 1751.[5] Spanish settlers developed small mines.

In 1833 a Mexican land grant of 8,677 acres (35.11 km2) was approved, which became La Aribac ranch, a Pima word for "small springs".[6] Charles Poston bought the ranch in 1856, and the reduction works for the Heintzelman Mine, at Cerro Colorado, were then erected at Arivaca. The Court of Private Land Claims eventually disallowed the Arivaca Land Grant.[7] The US Post Office was established April 10, 1878, with Noah W. Bernard as the first Postmaster;[5] still in operation at ZIP code 85601. Freighter and rancher Pedro Aguirre established a stage stop in Arivaca and the Buenos Aires Ranch. In 1879 he built the historic Arivaca Schoolhouse, which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2012, as the oldest standing school building in Arizona.

Arivaca was a camp for at least three United States Cavalry units during the Mexican Revolution - Troop B of the Connecticut National Guard/The First Company Governor's Horse Guards (1916), the Utah Cavalry (1917) and the 10th Cavalry (1917–20).

Arivaca mining district

editThe historic Arivaca mining district consists of over 100 old mines in the Las Guijas Mountains northwest, the San Luis Mountains to the southwest and Cobre Ridge to the southeast of the town. Gold, silver, lead, copper and tungsten production has been recorded starting in Spanish colonial times and continuing intermittently through the 1950s.[8]

Recent history

editArivaca had a population of 26 in the 1960 census.[9]

Arivaca had a small population until the Trico Electric Cooperative power lines arrived in the valley in 1956. In 1972 the Arivaca Ranch sold 11,000 acres to a land developer who subdivided the property into 40-acre parcels. Four years later, the dirt Arivaca Road was paved.

In 1980 author Philip Varney described Arivaca as a semi-ghost town.[10] In the 1980s and 1990s many new residents moved into the area, and a medical clinic, fire department, arts council, human resource office, community center and branch of Pima County Public Library were opened.

In 2012 the Arivaca Schoolhouse, the oldest standing schoolhouse in the state, was added to the National Register of Historic Places. A former nursing home was turned into the Arivaca Action Center with a focus on education, the arts, wellness, hospitality and sustainability. The AAC offers space for meetings, overnight guests, gardening, and physical therapy [citation needed].

Border issues

editPart of a travel corridor for asylum seekers and migrants, Arivaca is at one end of Project 28, the test of SBInet. SBInet was the effort by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and the Boeing Company to secure US land borders using technology. It was to involve 98-foot (30 m) high towers with radar and cameras that send information to bases in Tucson and Sells, where directions were to be sent out to specially equipped Border Patrol vehicles about targets for apprehension. Project 28 was the effort to test this strategy on a 28-mile (45 km) stretch flanking the border on either side of Sasabe. There were to be two towers on the Tohono O'Odham Nation west of the Baboquivari Mountains and 7 towers in the Altar Valley and southwest of Arivaca.[11] This project has been taken over by the Border Patrol and the number of towers reduced and relocated.

On May 30, 2009, Raul Flores and his 9-year-old daughter, Brisenia, were killed in a home-invasion in Arivaca during a robbery by rogue militia.[12] Two of the attackers were sentenced to death in early 2011, while the third received life without parole.[13]

On June 12, 2018, a United States Border Patrol agent was wounded in an early morning shootout with Mexican smugglers near Arivaca. The US Border Patrol agent was on foot patrol and alone, responding to a movement sensor activation in Chimney Canyon along a well-known smuggler's route, which leads north from the international boundary to Arivaca, about 10 miles north of the border. While investigating the activation, the agent was ambushed and fired upon and was shot in one of his hands and one of his legs, and several times more in his bulletproof vest. The agent who is also a paramedic was able to return fire and escape his attackers while applying first aid and retreating to his patrol vehicle, where he was able to call for assistance; eventually being evacuated via helicopter.[14]

The town of Arivaca has been called "...an epicenter of efforts in solidarity with migrants and refugees," according to a Crimethinc publication by a former desert aid worker. Furthermore, according to the book, migrants began to increasingly arrive at Arivaca after the September 11 attacks, as border agents pushed migrant traffic west of Nogales. This led to Arivaca becoming more heavily militarized. As a result, No More Deaths began working in the town in 2004.[15] As of 2014[update], there was a U.S. Border Patrol interior checkpoint being operated in the town, which was the subject of an ACLU of Arizona complaint, alleging both that the checkpoints are abusive and that agents unlawfully restricted the activities of protesters and photographers documenting their activities.[16][17]

Geography

editThe Arivaca community lies on the north side of the Arivaca Creek valley at an elevation of 3,643 feet (1,110 m). The Las Guijas Mountains rise to the northwest and the foothills of the San Luis Mountains are to the south. A unit of the Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge occupies the Arivaca Creek valley to the southeast of the town.[18]

Climate

editAccording to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Arivaca has a semi-arid climate, abbreviated "BSk" on climate maps.[19]

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 61 | — | |

| 1890 | 236 | — | |

| 1910 | 2,480 | — | |

| 1920 | 596 | −76.0% | |

| 1930 | 539 | −9.6% | |

| 2010 | 695 | — | |

| 2020 | 623 | −10.4% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[20] | |||

Arivaca first appeared as "Aravica Mines" on the 1860 U.S. Census when it was in the short-lived Arizona County in New Mexico Territory.[21] Of the 61 residents, 52 were White and nine were Black. The nine Black residents accounted for the largest community of Blacks in what was to be Arizona (Tucson then had eight). It would not report again until 1890 as the unincorporated village of Arivaca. It did not appear on the 1900 census. It next appeared as the "Arivaca Precinct" in 1910 through 1930, though this included the general area surrounding the village.[22] It reported a majority of "other" (likely Hispanic/Spanish) when the racial demographics were reported for the precinct in 1930.[23] With the combination of all county precincts into three districts in 1940, it did not formally appear again until 2010, when it was made a census-designated place (CDP).

Education

editThe settlement is served by Sopori Elementary School, Sahuarita Middle School, and Sahuarita High School, all part of the Sahuarita Unified School District.

Economy

editIn 2011 community members created Arivaca Alive, with a mission to develop programs and activities to increase the number of visitors to the community to support local businesses. Exposing visitors to the residents as part of a larger rebranding effort was an equally important goal. The group initiated First Saturdays in Arivaca with themed monthly events. In 2013 the group began a campaign branding Arivaca as a weekend destination built around the eco tourism attractions in the area including: birding, hiking, boating, gardening, and ghost town hunting. The organization sought to expand its reach to publicize other activities in the community throughout the year including: Dia de los Muertos, Arivaca Memories & Music Festival, Arivaca Film Festival Cinco de Mayo and Fourth of July Parade.

Transportation

editArivaca Road connects with I-19 at Amado, approximately 23 miles (37 km) to the northeast and with Arizona State Route 286 some 12 miles (19 km) to the west in Altar Valley.[24]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ a b Arivaca Archived September 17, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Arizona Department of Commerce, August 10, 2007. Accessed 2007-09-07.

- ^ "Zip Code Lookup". Archived from the original on June 15, 2011.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ a b Barnes, Will C.; Granger, Byrd (ed.) Arizona Place Names. 1997, University of Arizona Press, pp. 25–26. Quoted at "History and information about Arivaca, Arizona". Archived from the original on July 5, 2008. Retrieved March 30, 2009.

- ^ "Arivaca community profile" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 17, 2007. Retrieved September 7, 2007.

- ^ Barnes, Will C.; Granger, Byrd (ed.), Arizona's names : X marks the place. 1983, Falconer Pub. Co, pp. 20–30. Quoted at "History and information about Arivaca, Arizona". Archived from the original on July 5, 2008. Retrieved March 30, 2009.

- ^ "Arivaca Mining District (Las Guijas Mining District), Las Guijas & San Luis Mountains, Pima County, Arizona, USA". www.mindat.org.

- ^ "Arizona". World Book Encyclopedia. Vol. A. Chicago: Field Enterprises Educational Corporation. 1960. p. 557.

- ^ Varney, Philip (1980). "Eight: The Ruby Loop". Arizona's Best Ghost Towns. Flagstaff: Northland Press. p. 87. ISBN 0873582179. LCCN 79-91724.

- ^ Arivaca border issues/ Archived November 21, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ New Border Fear: Violence by a Rogue Militia New York Times, June 26, 2009

- ^ Arizona: Border Activist Sentenced to Death, New York Times, February 22, 2011

- ^ Allen, Keith; Almasy, Steve (June 13, 2018). "Border Patrol agent shot in Arizona gunfight was first responder for his own wounds". CNN. Retrieved July 25, 2019.

- ^ Ex-desert-aid worker, author. (July 2017). No wall they can build : a guide to borders & migration across North America. CrimethInc. Workers' Collective. ISBN 978-0-9989822-1-2. OCLC 992748218.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "Photographers' Rights At Issue As Arizona Community Rises Up Against "Occupying Army" of Border Patrol Agents". American Civil Liberties Union. April 16, 2014.

- ^ Feliciano, Ivette; Green, Zachary (December 15, 2019). "Life in a town with more Border Patrol agents than residents". PBS NewsHour. Retrieved December 16, 2019.

- ^ Arivaca, Arizona, 7.5 minute quad., USGS, 1996

- ^ "Arivaca, Arizona Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ^ "Territory of New Mexico" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 1860.

- ^ "Supplement for Arizona - Population, Agriculture, Manufactures, Mines and Quarries" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 1910.

- ^ "Arizona - Composition and Characteristics" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 1930. pp. 141–163.

- ^ Sells, Arizona-Sonora, 30x60 topographic quadrangle, USGS, 1994

Further reading

edit- Mary Noon Kasulaitis, 2002, "The Village of Arivaca: a Short History." Smoke Signal No. 75[permanent dead link], Tucson Corral of the Westerners.

- Mary Noon Kasulaitis, Spring 2006, "A Fenian in the desert: Captain John McCafferty and the 1870s Arivaca Mining Boom." The Journal of Arizona History.