John Anthony Walker Jr. (July 28, 1937 – August 28, 2014) was a United States Navy chief warrant officer and communications specialist convicted of spying for the Soviet Union from 1967 to 1985 and sentenced to life in prison.[2]

John Anthony Walker | |

|---|---|

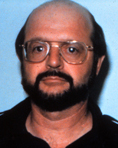

John Anthony Walker circa 1985 | |

| Born | John Anthony Walker Jr. July 28, 1937 Washington, D.C., U.S.[1] |

| Died | August 28, 2014 (aged 77) |

| Occupation(s) | United States Navy Chief Warrant Officer and communications specialist[2] Private investigator |

| Spouse |

Barbara Crowley

(m. 1957; div. 1976) |

| Children | 4, including Michael Walker (accomplice) Laura Walker (attempted accomplice) |

| Motive | Financial gain |

| Criminal charge | Espionage |

In late 1985, Walker made a plea bargain with federal prosecutors, which required him to provide full details of his espionage activities and testify against his co-conspirator, former senior chief petty officer Jerry Whitworth. In exchange, prosecutors agreed to a lesser sentence for Walker's son, former Seaman Michael Walker, who was also involved in the spy ring.[2] During his time as a Soviet spy, Walker helped the Soviets decipher more than one million encrypted naval messages,[3] organizing a spy operation that The New York Times reported in 1987 "is sometimes described as the most damaging Soviet spy ring in history."[4]

After Walker's arrest, Caspar Weinberger, President Ronald Reagan's Secretary of Defense, concluded that the Soviet Union made significant gains in naval warfare attributable to Walker's spying. Weinberger stated that the information Walker gave Moscow allowed the Soviets "access to weapons and sensor data and naval tactics, terrorist threats, and surface, submarine, and airborne training, readiness and tactics."[5]

In the June 2010 issue of Naval History Magazine, John Prados, a senior fellow with the National Security Archive in Washington, D.C., pointed out that after Walker introduced himself to Soviet officials, North Korean forces seized USS Pueblo in order to make better use of Walker's spying. Prados added that North Korea subsequently shared information gleaned from the spy ship with the Soviets, enabling them to build replicas and gain access to the U.S. naval communications system, which continued until the system was completely revamped in the late 1980s.[6] It has emerged in recent years that North Korea acted alone and the incident actually harmed North Korea's relations with most of the Eastern Bloc.[7]

Early life

editWalker was born in Washington, D.C., on July 28, 1937,[8] and attended high school in Scranton, Pennsylvania.[1] After dropping out of high school, Walker and a friend staged a series of burglaries on May 27, 1955. Their loot included two tires, four quarts of oil, six cans of cleaner, and $3 in cash. The pair evaded police during a high-speed chase, but were arrested two days later.[9] He was offered the option of jail or the military.[1][10] He enlisted in the Navy in 1955, and successfully advanced as a radioman to chief petty officer in eight years. While stationed in Boston, Walker met and married Barbara Crowley, and they had four children together, three daughters and a son. While stationed on the nuclear-powered Fleet Ballistic Missile (FBM) submarine USS Andrew Jackson in Charleston, South Carolina, Walker opened a bar, which failed to turn a profit and immediately plunged him into debt.[1] In 1965 Walker transferred to the newly built FBM, USS Simon Bolivar, where he received a top secret crypto clearance to work in the submarine's communications spaces. He and other members of the submarine's communications team were members of the John Birch Society, distributing literature about the organization to crew members and to friends ashore, where Walker attempted the playboy lifestyle.[9]

Spy ring

editJohn Walker was promoted to warrant officer in March 1967 and in April was assigned as a communications watch officer at the headquarters of COMSUBLANT in Norfolk, Virginia, where his responsibilities included "running the entire communications center for the submarine force...."[9] Walker began spying for the Soviets in late 1967,[11][12] when, distraught over his financial difficulties, he walked into the old Soviet embassy in Washington, D.C., sold a top-secret document (a radio cipher card) for several thousand dollars, and negotiated an ongoing salary of US$500 (equivalent to $4,569 in 2023) to US$1,000 (equivalent to $9,138 in 2023) a week.[1]

Soviet KGB general Boris Aleksandrovich Solomatin, stationed at Washington, D.C. 1966–68, "played a key role in the handling of John Walker".[13] Walker justified his treachery by claiming that the first classified Navy communications data he sold to the Soviets had already been completely compromised when the North Koreans had captured the U.S. Navy communications surveillance ship, USS Pueblo.[14] Yet the Koreans captured Pueblo in late January 1968 – many weeks after Walker had betrayed the information.[11] Furthermore, a 2001 thesis presented at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College using information obtained from Soviet archives and from Oleg Kalugin, indicated that the Pueblo incident may have taken place because the Soviets wanted to study equipment described in documents supplied to them by Walker.[15]

It has emerged in 2012 that North Korea acted alone and the incident actually harmed North Korea's relations with most of the Eastern Bloc.[7]

In the spring of 1968 John Walker's wife discovered items in his desk at home causing her to suspect he was acting as a spy.[9] Walker continued spying, receiving an income of several thousand dollars per month for supplying classified information. Walker used most of the money to pay off his delinquent debts and to move his family into better neighborhoods, but he also set aside some for future investment, such as turning around the fortunes of his money-losing bar by hiring a skilled bartender.[1] While Walker occasionally used the services of his wife, Barbara Walker, he anticipated the possibility of losing access to classified material due to reassignment. Walker's chance to seek further assistance came in September 1969 when he became the deputy director of the Radioman A and B schools at Naval Training Center San Diego.[9] There, Walker befriended student Jerry Whitworth.[1]

Walker was transferred from San Diego in December 1971 to become the communications officer aboard the supply ship USS Niagara Falls.[9] Whitworth, who would become a Navy senior chief petty officer/senior chief radioman, agreed to help Walker gain access to highly classified communications data in 1973;[1] and served aboard Niagara Falls after Walker retired from the Navy. Transfer to the staff of commander of the Amphibious Force, Atlantic Fleet had stopped Walker's access to the data the Soviets wanted, but he recruited Whitworth to keep the data flowing – softening the idea of espionage by telling him the data would go to Israel, an ally of the United States.[9] Later, when Whitworth realized the data was going to the Soviets instead of Israel, he nonetheless continued supplying Walker with information, until Whitworth's own retirement from the Navy in 1983.

In 1976, Walker retired from the Navy in order to give up his security clearance, as he believed certain superior officers of his were too keen on investigating lapses in his records. Walker and Barbara had also divorced. However, Walker did not end his espionage work, and began looking more aggressively among his children and family members for assistance (Walker was a private investigator during this time).

By 1984 (after Whitworth's retirement in 1983) Walker recruited his older brother Arthur James Walker (August 5, 1934 – July 5, 2014), a retired lieutenant commander who served from 1953 until 1973 and then went to work at a military contractor, and his son Michael Lance Walker (born November 2, 1962), an active duty seaman since 1982.[1] Walker had also attempted to recruit his youngest daughter, who had enlisted in the United States Army, but she cut her military career short when she became pregnant and refused her father's offer to pay for an abortion, instead deciding to devote herself to full-time motherhood. Walker then turned his attention to his son, who had drifted during much of his teenage years and dropped out of high school. Walker gained custody of his son, put him to work as an apprentice at his detective agency in order to prepare him for espionage and encouraged him to re-enroll in high school to earn a diploma, then to enlist in the Navy.

When Walker began spying, he worked as a key supervisor in the communications center for the U.S. Atlantic Fleet's submarine force, and he would have had knowledge of top-secret technologies, such as the SOSUS underwater surveillance system, which tracks underwater acoustics via a network of submerged hydrophones.[16][17] It was through Walker that the Soviets became aware that the U.S. Navy was able to track the location of Soviet submarines by the cavitation produced by their propellers. After this, the propellers on the Soviet submarines were improved to reduce cavitation.[18] The Toshiba-Kongsberg scandal was disclosed in this activity in 1987.[19] It is also alleged that Walker's actions precipitated the seizure of USS Pueblo. CIA historian H. Keith Melton states on the show Top Secrets of the CIA, which aired on the Military Channel, among other occasions, at 0400CST, February 5, 2013:

[The Soviets] had intercepted our coded messages, but they had never been able to read them. And with Walker providing the code cards, this was one-half of what they needed to read the messages. The other half they needed were the machines themselves. Though Walker could give them repair manuals, he couldn't give them machines. So, within a month of John Walker volunteering his services, the Soviets arranged, through the North Koreans, to hijack a United States Navy ship with its cipher machines, and that was the USS Pueblo. And in early 1968 they captured the Pueblo, they took it into Wonsan Harbor, they quickly took the machines off ... flew 'em to Moscow. Now Moscow had both parts of the puzzle. They had the machine and they had an American spy, in place, in Norfolk, with the code cards and with access to them.

In 1990, The New York Times journalist John J. O'Connor reported, "It's been estimated by some intelligence experts that Mr. Walker provided enough code-data information to alter significantly the balance of power between Russia and the United States".[20] Asked later how he had managed to access so much classified information, Walker said, "KMart has better security than the Navy".[21] According to a report presented to the Office of the National Counterintelligence Executive in 2002, Walker is one of a handful of spies believed to have earned more than a million dollars in espionage compensation,[10] although The New York Times estimated his income at only $350,000.[20]

Theodore Shackley, the CIA station chief in Saigon, asserted that Walker's espionage may have contributed to diminished B-52 bombing strikes, that the forewarning gleaned from Walker's espionage directly affected the United States' effectiveness in Vietnam.[22] Independent analysis of Walker's methods by an American Naval officer in Cold War London, Lieutenant Commander David Winters, led to operational introduction of technologies – such as over-the-air rekeying – that finally closed security gaps previously exploited by the Walker spy ring.[citation needed]

Arrest and imprisonment

editJohn and Barbara Walker divorced in 1976. Their marriage was marked by physical abuse and alcohol. By 1980, Barbara had begun regularly abusing alcohol and was very fearful for her children. She wanted the children not to become involved in the spy ring; that led to constant disagreement with John. Barbara tried several times to contact the Boston office of the FBI, but she either hung up or was too drunk to speak. In November 1984 she again contacted the Boston office and in a drunken confession reported that her ex-husband spied for the Soviet Union. She did not then know that their son Michael had meanwhile become an active participant in espionage; she later admitted she would not have reported the spy ring had she known her son was involved.[1]

The Boston office of the FBI interviewed Barbara Walker and initially considered her story to be the rantings of a drunken, bitter woman trying to "drop a dime" on an ex-husband. Since Barbara's report regarded a person who lived in Virginia, the Boston office sent the report to the Norfolk office. When the FBI in Norfolk reviewed the report, the counterintelligence squad concluded it might be a truthful report and initiated a discreet investigation. The FBI conducted an interview of Walker's daughter, Laura, who confirmed that her father was a KGB spy and said that he had tried to recruit her into his espionage ring while she was in the U.S. Army.

When both Barbara Walker and Laura Walker passed polygraph examinations, electronic surveillance was authorized by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court against John Walker. In May 1985 the FBI learned through the electronic surveillance that it was likely that John Walker would travel out of town on the weekend of May 18–19, 1985. On May 19 Walker left his house in Norfolk and was followed covertly by the FBI to the Washington, D.C., area, where the surveillance was joined by personnel from the FBI's Washington field office. Later that evening about 8:30 p.m. he drove to a rural area in Montgomery County, Maryland, where he was seen placing a package in a wooded area near a "No Hunting" sign. The FBI retrieved the package that was found to have 124 pages of classified information stolen from the aircraft carrier USS Nimitz, where Walker's son, Michael, was assigned.

John Walker was arrested during the early morning hours of May 20, 1985, by a team of agents from the Norfolk and Washington FBI field offices. The FBI apprehended Walker himself at a motel in Montgomery County by telephoning his hotel room and telling him that his car had been hit in an accident.[1] Barbara Walker was eventually not prosecuted, because of her role in disclosing the spy ring.[1][10]

Former KGB agent Victor Cherkashin, however, described in his 2005 book Spy Handler that Walker was compromised by FBI spy Valery Martynov, who allegedly overheard officials in Moscow speaking about Walker.[23] Martynov was a Line X (Technical & Scientific Intelligence) officer at the Washington rezidentura. Working for the U.S., he revealed the identities of fifty Soviet intelligence officers operating from the embassy and technical and scientific targets that the KGB had penetrated.

Michael Walker was arrested aboard Nimitz, where investigators found a footlocker full of copies of classified matter. He had to be taken off his ship under guard to avoid getting beaten by sailors and Marines. Arthur Walker and Jerry Whitworth were arrested by the FBI in Norfolk, Virginia, and Sacramento, California, respectively. Arthur Walker was the first member of the espionage ring to go to trial. During the arrest of Arthur Walker, he was read his rights and repeatedly told he needed to stay silent until he could retain a lawyer, but kept admitting complicity in an effort to "show remorse". He was tried, convicted, and sentenced to three life sentences in a federal district court in Norfolk.

Walker cooperated somewhat with authorities, enough to form a plea bargain that reduced the sentence for his son. He agreed to submit to an unchallenged conviction and life sentence, to provide a full disclosure of the details of his spying and to testify against Whitworth, in exchange for a pledge from the prosecutors that the maximum sentence requested for Michael was 25 years imprisonment, which was later Michael's sentence.[2][24]

All the members of the spy ring besides Michael Walker received life sentences for their role in the espionage. Whitworth was sentenced to 365 years in prison and fined $410,000 for his involvement. Whitworth was incarcerated at the United States Penitentiary, Atwater, a high-security federal prison in California. Walker's older brother Arthur received three life sentences plus 40 years and died in the Butner Federal Correctional Complex in Butner, North Carolina on July 5, 2014, six weeks before the death of his younger brother.[25]

Walker's son, Michael, who had a relatively minor role in the ring and agreed to testify in exchange for a reduced sentence, was released from prison on parole in February 2000.[1] Walker was incarcerated at FCC Butner, in the low security portion.[26] He was said to suffer from diabetes mellitus and stage 4 throat cancer.[1][27]

FBI Lead Case Agent, Robert ’Bob’ Hunter and his team investigated, surveilled, and accomplished what had never before been done in the history of the FBI, and caught Walker in the act of espionage itself. On May 20 at 3:30 a.m. in front of a hotel elevator, Hunter and Jimmy Kaluch confronted Walker with guns drawn. Walker also drew his gun, resulting in a stand-off which Hunter explains was resolved when we ‘talked [Walker] into dropping his gun.’ [28]

Death

editWalker died while he was suffering from cancer and diabetes on August 28, 2014, while still in prison.[29][30] He would have become eligible for parole in 2015.[31]

In popular culture

editIn 1990, Walker's life from his navy career just before his recruitment as a spy to his and his son's arrest by the FBI was dramatized in a two-part TV movie called Family of Spies on CBS. Walker was portrayed by Powers Boothe. The book Blind Man's Bluff: The Untold Story of American Submarine Espionage, published in 1998, includes a description of the Walker spy ring role in its dangerous compromise of technical secrets of some of the vital tactical capabilities of U.S. Navy nuclear submarines and critical covert intelligence gathering operations during the Cold War.

See also

edit- Aldrich Ames American CIA counterintelligence officer convicted of spying for the Soviet Union and Russia in 1994.

- Robert Hanssen American FBI agent convicted of spying for the Soviet Union and Russia in 2001.

- KL-7 "Adonis" cipher machine (U.S. Navy 1950s – 1970s)

- KW-37 "Jason" cipher machine (U.S. Navy 1950s – 1990s)

- USS Niagara Falls (AFS-3), a ship that Walker served on as CMS custodian

- Hans-Thilo Schmidt

- Hitori Kumagai

- 1985: The Year of the Spy

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Earley, Pete. "Family of Spies: The John Walker Jr. Spy Case". CourtTV. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Recent U.S. Spy Cases | CNN". CNN. Archived from the original on December 10, 2008. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

1985 -- Walker family

- ^ "米海軍スパイ事件の教訓" [Lessons from the US Navy Spy Case] (PDF). 防衛取得研究 [Defense Acquisition Research] (in Japanese) (1 ed.). June 19, 1999. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 22, 2011.

- ^ Shenon, Philip (January 4, 1987). "In short: nonfiction". New York Times. Retrieved November 16, 2007.

- ^ "The Navy's Biggest Betrayal - U.S. Naval Institute". www.usni.org. June 2010. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ Prados, John. The Navy's Biggest Betrayal. Naval History 24, no. 3 (June 2010): 36.

- ^ a b Lerner, Mitchell; Shin, Jong-Dae (April 20, 2012). "New Romanian Evidence on the Blue House Raid and the USS Pueblo Incident. NKIDP e-Dossier No. 5". Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- ^ Weil, Martin (August 30, 2014). "John A. Walker Jr., who led family spy ring, dies at 77". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bamford, James (1986). "The Walker Espionage Case". Proceedings. 112 (5). United States Naval Institute: 111–119.

- ^ a b c Herbig, Katherine L. and Martin F. Wiskoff. (July 2002) Espionage against the United States by American citizens, 1947-2001. FAS website. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- ^ a b Pete Earley (1989). Family of Spies: Inside the John Walker Spy Ring. Bantam Books. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-553-28222-1.

- ^ Sontag, Sherry; Drew, Christopher; Annette Lawrence Drew (1998). Blind Man's Bluff: The Untold Story of American Submarine Espionage (paperback reprint ed.). HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-103004-X. OCLC 42633517.

- ^ Earley, Pete (April 23, 1995). "INTERVIEW WITH THE SPY MASTER". Washington Post. Retrieved March 12, 2022.

- ^ "KW-7 and John Walker".

- ^ Heath, Laura J. (2005). "Analysis of the Systemic Security Weaknesses of the U.S. Navy Fleet Broadcasting System, 1967–1974, as Exploited by CWO John Walker" (PDF). U.S. Army Command and General Staff College Master's Thesis.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "The John Walker Spy Case: Secrets of the Deep Agent May be Linked to USS Pueblo". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. May 18, 1986.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Cold War Strategic ASW". 1986. Archived from the original on June 18, 2012.

- ^ "Eaglespeak".

- ^ "The Toshiba-Kongsberg Incident" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 13, 2014.

- ^ a b O'Connor, John J. (February 4, 1990). "TV View; American spies in pursuit of the American dream". NY Times. Retrieved November 16, 2007.

- ^ Johnson, Reuben F (July 23, 2007). "The ultimate export control: why F-14s are being put into a shredder". The Weekly Standard. 012 (42). Archived from the original on February 3, 2016. Retrieved November 16, 2007.

- ^ Barron, John (1987). Breaking the Ring: The Bizarre Case of the Walker Family Spy Ring. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin. p. 23.

They usually had forewarning of the B-52 strikes. Even when the B-52s diverted to secondary targets because of weather, they knew in advance which targets would be hit. Naturally, the foreknowledge diminished the effectiveness of the strikes because they were ready. It was uncanny. We never figured it out.

[— Theodore Shackley, CIA station chief in Saigon from 1968-1973] - ^ Cherkashin, Victor. Spy Handler. New York: Basic Books, 2005. (Page 183)

- ^ Time, Belated concern, Time Inc. (November 11, 1985) Accessed November 16, 2007.

- ^ Watson, Denise M; King, Lauren (July 10, 2014). "Convicted spy Arthur Walker dies in prison in N.C." Virginian Pilot. Archived from the original on October 6, 2015. Retrieved July 11, 2014.

- ^ "Inmate Locator". www.bop.gov. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ How to Publish a Book by an Odious Person The Washington Post. Accessed August 26, 2013.

- ^ Dead Drop: The Capture of John Walker

- ^ Yardley, William (August 30, 2014). "John A. Walker Jr., Ringleader of Spy Family, Dies at 77". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- ^ AP (August 30, 2014). "Ex-US sailor John A. Walker who spied for Soviets dies in prison hospital". The Telegraph.

- ^ Denise M. Watson (August 29, 2014). "Spy ring mastermind John Walker dies in N.C. prison". PilotOnline.com. Archived from the original on August 31, 2014. Retrieved August 29, 2014.

Further reading

edit- Thomas B. Allen and Norman Polmar; Merchants of Treason: America's Secrets for Sale: New York: Delacorte Press, 1988, ISBN 0-385-29591-X (about half of the book is devoted to the Walker case)

- John Barron; Breaking the Ring: The Bizarre Case of the Walker Family Spy Ring; Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1987, ISBN 0-395-42110-1

- Howard Blum; I Pledge Allegiance: The True Story of the Walkers: an American Spy Family; Simon & Schuster Books, 1987, ISBN 0-671-62614-0

- Kneece, Jack; Family Treason: The Walker Spy Case; Paperjacks, 1988, ISBN 0-7701-0793-1

- Robert W. Hunter; Spy Hunter: Inside the FBI Investigation of the Walker Espionage Case; Naval Institute Press, 1999, ISBN 1-55750-349-4

- Pete Earley; Family of Spies: Inside the John Walker Spy Ring; Bantam Books, 1989, ISBN 0-553-28222-0

- "The Navy's Biggest Betrayal", Naval History Magazine

- Offley, Ed; Scorpion Down: The Untold Story of the USS Scorpion; Chapter 12 "The Fatal Triangle"; New York, Basic Books, 2007, ISBN 978-0-465-05185-4

- Walker, John Anthony; My Life as a Spy; Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books, 2008, ISBN 978-1-59102-659-4

- Walker, Laura; Daughter of Deceit: The Human Drama Behind the Walker Spy Case; W Pub Group, 1988, ISBN 978-0849906596