Assassin's Creed is a 2007 action-adventure game developed by Ubisoft Montreal and published by Ubisoft. It is the first installment in the Assassin's Creed series. The video game was released for PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360 in November 2007. A Microsoft Windows version titled Assassin's Creed: Director's Cut Edition containing additional content was released in April 2008.

| Assassin's Creed | |

|---|---|

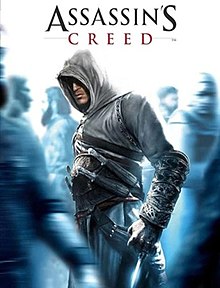

Game cover art | |

| Developer(s) | Ubisoft Montreal |

| Publisher(s) | Ubisoft |

| Director(s) | Patrice Désilets |

| Producer(s) | Jade Raymond |

| Designer(s) | Maxime Béland |

| Programmer(s) | Mathieu Mazerolle |

| Artist(s) | Raphaël Lacoste |

| Writer(s) | Corey May |

| Composer(s) | Jesper Kyd |

| Series | Assassin's Creed |

| Engine | Scimitar |

| Platform(s) | |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Action-adventure, stealth |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

The plot is set in a fictional history of real-world events, taking place primarily during the Third Crusade in the Holy Land in 1191. The player character is a modern-day man named Desmond Miles who, through a machine called the Animus, relives the genetic memories of his ancestor, Altaïr Ibn-La'Ahad. Through this plot device, details emerge about a millennia-old struggle between two factions: the Assassin Brotherhood (inspired by the real-life Order of Assassins), who fight to preserve peace and free will, and the Templar Order (inspired by the Knights Templar military order), who seek to establish peace through order and control. Both factions fight over powerful artifacts of mysterious origins known as Pieces of Eden to gain an advantage over the other. The 12th-century portion of the story follows Altaïr, an Assassin who embarks on a quest to regain his honour after botching a mission to recover one such artifact from the Templars. Altaïr is stripped of his status as Master Assassin and is given nine targets spread out across the Holy Land that he must find and assassinate for his redemption.

The gameplay focuses on using Altaïr's combat, stealth, and parkour abilities to defeat enemies and explore the environment. The game features counter-based hack-and-slash combat, social stealth (the ability to use crowds of people and the environment to hide from enemies), and a large open world comprising various regions of the Holy Land, primarily the cities of Masyaf, Jerusalem, Acre, and Damascus, all of which have been accurately recreated to fit the game's time period. While most of the game takes place within a simulation based on Altaïr's memories, the player will occasionally be forced out of the Animus to play as Desmond in the modern day. Here, they are restricted to exploring a small laboratory facility, as Desmond has been kidnapped by Abstergo Industries, a shady corporation looking for specific information within Altaïr's memories that will further their enigmatic goals.

Upon release, Assassin's Creed received generally positive reviews, with critics praising its storytelling, visuals, art design, and originality, while criticism mostly focused on the repetitive nature of its gameplay. Assassin's Creed won several awards at the 2006 E3 and several end-year awards after its release. The game spawned two spin-offs: Assassin's Creed: Altaïr's Chronicles (2008) and Assassin's Creed: Bloodlines (2009), which exclude the modern-day aspect and focus entirely on Altaïr. A direct sequel, Assassin's Creed II, was released in November 2009. The sequel continues the modern-day narrative following Desmond but introduces a new storyline set during the Italian Renaissance in the late 15th century and a new protagonist, Ezio Auditore da Firenze. Since the release and success of Assassin's Creed II, subsequent games have been released with various other Assassins and periods.

Gameplay

editAssassin's Creed is an action-adventure game,[5] set in an open-world environment,[6] which is played from a third-person view in which the player primarily assumes the role of Altaïr, as experienced through protagonist Desmond Miles. The game's primary goal is to carry out a series of assassinations ordered by Al Mualim, the Assassins' leader, after Ataïr botches the first mission at Solomon’s Temple and must redeem himself. To achieve this goal, the player must travel from the Brotherhood's headquarters in Masyaf, across the terrain of the Holy Land known as the Kingdom, where the player can freely ride a horse[7] to one of three cities—Jerusalem, Acre, or Damascus—to find the Brotherhood agent in that city. There, the agent, in addition to providing a safe house, gives the player minimal knowledge about the target and requires them to perform additional reconnaissance missions before attempting the assassination. These missions include eavesdropping, interrogation, pickpocketing, and completing tasks for informers and fellow Assassins.[8] After completing each assassination, the player returns to the Brotherhood and is rewarded with a better weapon or upgrade before going after the next target. The player can also be given a set of targets and is free to choose the order they pursue them. The player may also take part in several side objectives, including climbing tall towers to map out the city and saving citizens being threatened or harassed by the city guards. There are also various additional memories that do not advance the plot, such as hunting down and killing Templar Knights and flag collecting.[8]

The player is made aware of how noticeable Altaïr is to enemy guards and the state of alert in the local area via the Social Status Icon. To perform many assassinations and other tasks, the player must consider the use of actions distinguished by their type of profile. Low-profile actions allow Altaïr to blend into nearby crowds, pass by other citizens, or perform other non-threatening tasks that can be used to hide and reduce the alertness level. The player can also use Altaïr's retractable hidden blade to attempt low-profile assassinations. High-profile actions are more noticeable and include running, scaling the sides of buildings to climb to higher vantage points, and attacking foes; performing these actions at certain times may raise the local area's awareness level. Once the area is at high alert, crowds run and scatter while guards attempt to chase and bring down Altaïr. To reduce the alert level, the player must control Altaïr to break the guards' line of sight and then find a hiding space, such as a haystack or rooftop garden, or blend in with the citizens sitting on benches or wandering scholars.[8] Should the player be unable to escape the guards, they can fight back using swordplay maneuvers.[9]

The player's health is described as the level of synchronization between Desmond and Altaïr's memories; should Altaïr suffer injury, it is represented as a deviation from the actual events of the memory rather than physical damage. If all synchronization is lost, the current memory that Desmond is experiencing will be restarted at the last checkpoint. When the synchronization bar is full, the player has the additional option to use Eagle Vision, which allows the computer-rendered memory to highlight all visible characters in colours corresponding to whether they are allies (blue), foes (red), neutral (white), or the target of their assassination (gold). Due to Altaïr's memories being rendered by the computer of the Animus project, the player may experience glitches in the rendering of the historical world, which may help the player to identify targets, or can be used to alter the viewpoint during in-game scripted scenes should the player react fast enough when they appear.[8]

Plot

editIn 2012, bartender Desmond Miles (Nolan North) is kidnapped by agents of Abstergo Industries, the world's largest pharmaceutical conglomerate, and is taken to their headquarters in Rome, Italy. Under the supervision of Dr. Warren Vidic (Philip Proctor) and his assistant Lucy Stillman (Kristen Bell), Desmond is forced to enter a machine called the Animus, which can translate his ancestors' genetic memories into a simulated reality. Vidic instructs Desmond to relive the early years of Altaïr Ibn-La'Ahad (Philip Shahbaz), a senior member of the Assassin Brotherhood during the Third Crusade.

In 1191, Altaïr and two fellow Assassins—brothers Malik (Haaz Sleiman) and Kadar Al-Sayf (Jake Eberle)[10]— are sent to Solomon's Temple to retrieve an artifact known as the Apple of Eden from the Brotherhood's sworn enemies, the Knights Templar. Blinded by arrogance, Altaïr botches the mission, resulting in Kadar's death; however, Malik is able to grab the Apple before escaping. Although Altaïr later partially redeems himself by fighting off a Templar attack on the Assassin home base of Masyaf, his mentor and superior, Al Mualim (Peter Renaday), demotes and orders him to assassinate nine individuals in order to regain his previous position and honour:[11]

- Tamir (Ammar Daraiseh), an arms merchant in Damascus selling weapons to both the Crusaders and Saracens.

- Garnier de Nablus (Hubert Fielden), the leader of the Knights Hospitalier, who conducts mind-altering experiments on patients at his hospital in Acre.

- Talal (Jake Eberle), the leader of a gang of slavers in Jerusalem.

- Abu'l Nuquod (Fred Tatasciore), a pompous trader and regent of Damascus stealing money intended to fund the war.

- William V, Marquess of Montferrat (Harry Standjofski), Acre's cruel and abusive regent.

- Majd Addin (Richard Cansino; based on Baha ad-Din ibn Shaddad), a tyrant who rules Jerusalem through fear by holding public executions.

- Master Sibrand (Arthur Holden), the paranoid leader of the Knights Teutonic, who plans to betray the Crusaders by blocking the ports of Acre.

- Jubair al Hakim (Fred Tatasciore), a scholar using his position to seize and destroy all written knowledge in Damascus.

- Robert de Sablé (Louis-Philippe Dandenault), the Grand Master of the Templars who has been taking advantage of the Crusade to further his Order's ideological goals.

As Altaïr eliminates each target, he discovers all nine are Templars who had conspired to retrieve the Apple, revealed to be a relic of a long-forgotten civilization said to possess god-like powers. He also comes to question the nature of Al Mualim's orders while slowly becoming more humble and wise and making amends with Malik. During his assassination attempt on Robert de Sablé, Altaïr is tricked with a decoy: a Templar named Maria Thorpe (Eleanor Noble). Maria reveals that de Sablé had anticipated the Assassins would come after him and went to negotiate an alliance between the Crusaders and Saracens against them.

Sparing Maria's life, Altaïr confronts Robert in the camp of King Richard I (Marcel Jeannin) and exposes his crimes. Unsure of whom to believe, King Richard suggests a duel to determine the truth, remarking that God will decide the victor. After Altaïr mortally wounds him, Robert identifies Al Mualim as the final conspirator, revealing that the latter has betrayed both the Assassins and Templars to acquire the Apple. Altaïr returns to Masyaf, where Al Mualim has used the Apple to enthrall the population, as part of his plan to end the Crusade and all conflict in the world by imposing order by force. With the help of Malik and several Assassins brought for backup, Altaïr storms the citadel and confronts Al Mualim in the gardens, resisting the Apple's powers and killing his mentor. He then tries to destroy the artifact, but instead unlocks a map showing the locations of countless other Pieces of Eden around the world.[11]

In the present, the Assassins launch an unsuccessful attack on the Abstergo facility to rescue Desmond, resulting in most of them being killed. After completing Altaïr's memories, Vidic reveals to Desmond that Abstergo is a front for the modern-day Templars, seeking to find the remaining Pieces of Eden. With Desmond no longer useful, Vidic's superiors order him killed, but Lucy, who is implied to be an Assassin mole, convinces them to keep him alive for further testing. Desmond is left alone in his room, where he discovers strange drawings describing an upcoming catastrophic event.[11]

Development

editAfter completing Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time near the end of 2003, Patrice Désilets was instructed to begin work on the next Prince of Persia game, with plans to release it on the seventh-generation consoles. As Microsoft and Sony had not yet revealed their next consoles, the game's initial development from January 2004 was aimed as a PlayStation 2 title, following the same linear approach that The Sands of Time had taken.[12] As more information came in about the capabilities of the next-generation consoles by September 2004, Désilets' team considered expanding the Prince of Persia acrobatic gameplay into an open world that would be feasible on the newer systems.[12][13]

Désilets wanted to move away from the lead character being a prince simply waiting for his reign to start, but a character that wanted to strive to be a king. He came upon one of his university books on secret societies and its first material related to the Order of Assassins and recognized that he could have the lead character in the game as the second-highest Assassin, seeking to be the leader of the group.[13] The game began work under the title Prince of Persia: Assassin,[14] or Prince of Persia: Assassins,[13] inspired by Hassan-i Sabbah's life and making heavy use of Vladimir Bartol's novel Alamut.[15][16] The Assassin character was fleshed out throughout the game's three-year development in an iterative fashion. The team had some idea of how the character dressed from Alamut and other historical works in all-white robes and a red belt but had to envision how to detail this in the game.

One of the first concept sketches, drawn by animator Khai Nguyen, suggested the concept of a bird of prey, which resonated with the team. The Assassin was named Altaïr, meaning "bird of prey" in Arabic, and eagle imagery was used heavily in connection to the Assassins.[13] The team took some creative routes to meet narrative goals and avoid the technical limitations of the consoles. Altaïr was to be a heroic character with a bit of a rough edge, and the artist borrowed elements of the G.I. Joe character Storm Shadow, a similarly skilled hero.[13] Rendering long flowing robes was impossible on the newer hardware, so they shortened the robe and gave it a more feathered look, resonating the bird of prey imagery.[13] Similar routes were taken with other parts of the gameplay to take liberties with accuracy to make the game fun to play. The team wanted Altaïr's parkour moves to look believable but sacrificed realism for gameplay value, allowing the player to make maneuvers otherwise seemingly impossible in real-life. Having leaps of faiths from high vantage points into hay piles and using hay piles to hide from guards was a similar concept borrowed from Hollywood films; Désilets observed that Alamut described similar actions that the Assassins had undertaken.[13]

To drive the story, the team had to devise a goal that both the Assassins and Templars were working towards. Philippe Morin suggested using the Apple of Eden, which the team initially thought humorous for everyone to fight over an apple; however, as they researched, the team found that many medieval paintings of royalty and other leaders holding spherical objects similar to globus cruciger which represented power and control, and recognized that an artifact named the Apple of Eden would fit well into this concept.[13]

Among this work was the idea of the Animus, which came about after the team decided to focus on the Assassins. The team considered that the player would travel through several cities and potentially recount numerous assassinations over the past thousand years, including notable ones such as John F. Kennedy's, which would require some time travelling. Désilets had seen a program on DNA and human history and was inspired by the idea that DNA could store human memories, which prompted the idea that they could have an in-game machine that could be used for time and location jumps and explain other aspects of the game's user interface to the player. Désilets considered this similar to what they had established in The Sands of Time. There, the game effectively is a story told by the Prince, and while in the game, should the player-character die, this is treated as a mistelling of the Prince's story, allowing the player to back up and retry a segment of the game.[13] Ubisoft's marketing was not keen on the Animus idea, believing players would be confused and disappointed that the game was not a truly medieval experience. Due to this, the game's first trailer shown at the 2006 Electronic Entertainment Expo (E3) focused heavily on medieval elements.[13] Later marketing materials closer to the game's release hinted more directly at the science fiction elements of the game.[17]

The game cost $15 million to $20 million to develop and was in the works for four years.[18] The game had a marketing budget of $10 million.[19]

Design

editInitial work on the game was to expand out various systems from Prince of Persia to the open world concept with a team of 20 at Ubisoft Montreal.[14] A new next-generation game engine, the Scimitar engine, was created to support the open world, though this would take about two years to complete, during which the team used the Sands of Time engine for development; Scimitar eventually was renamed to AnvilNext and been used for most of the following Assassin's Creed games and other titles at Ubisoft.[14] Elements like wall-climbing were made more fluid, and the team worked to smooth other animation sequences; much of the improvements here came from programmer Richard Dumas and animator Alex Drouin, both of whom had worked together on the same elements in Sands of Time.[13] Level designers and artists recreating historical structures had to work together to ensure nearly every building could be climbable while still holding the game's historical appearances.[20] This also helped them to give the feeling to the player that they had as much freedom as possible within the game, a concept that had originated from the success of the Grand Theft Auto series.[20][13]

In contrast to Prince of Persia, where the general path that the player takes through a level is predefined, the open-world approach of this game required them to create cities that felt realistic and accurate to historical information while the player still had full freedom to climb and explore. Outside of special buildings, they crafted their cities like Lego bricks, with a second pass to smooth out the shapes of the cities to help with pathfinding and other facets of the enemy artificial intelligence.[13] To encourage the player to explore, they included the various viewpoint towers that help to reveal parts of the map. Historically, these cities had such landmark towers, and inspired by those, the developers incorporated them into the map, making these points of interest and challenges for players to drive them to climb them.[13] Another factor was guiding the player and devising missions for the player that still gave the player freedom for how to approach it but still created specific moments they wanted the player to experience. For these cases, they used simple animations developed in Adobe Flash to lay out the fundamentals of what actions they wanted and then crafted levels and missions around those.[13]

As they started to recognize the need for cities in this open-world game, Désilets wanted to make sure they were also able to simulate large crowds, as this had been a limiting factor due to hardware limitations during the development of The Sands of Time; with the PlayStation 2 hardware, they could only support having up to eight characters on screen for The Sands of Time, but the next-generation hardware was able to support up to 120 people.[20] Having crowds in the game also led to the concept of social stealth, where the main character could mask themselves in the open, in addition to staying out of sight on rooftops.[13] Désilets had come from an acting background, and one element he had incorporated into the game was to make the player-character feel more like they were controlling parts of a puppet so that the character would appear more human. This led to the use of high- and low-profile action in gameplay, which partially expressed the character's emotions and allowed the player to continue to control the character during the game's cutscenes.[17]

The fundamentals of gameplay were completed within nine to twelve months, and another year was spent improving it before they presented the game to Ubisoft's executives in Paris.[13] Jade Raymond was brought in in late 2004 to serve as the game's producer, helping with the team's growth and the game's direction.[13][21] From late 2005 to early 2006, following nearly two years of development, the concept for Prince of Persia: Assassins had the game's titular prince AI-controlled, watched over by the player-controlled Assassin that served as the Prince's bodyguard and rescued the Prince from various situations.[12] Ubisoft's management and the development had debates on this direction; Ubisoft's management wanted another game in the Prince of Persia franchise and was not keen on releasing a game with that name where the Prince was not the lead character. The development team countered that with a new generation of consoles, they could potentially make it a new intellectual property.[14][13] Near the 2006 Game Developers Conference, Ubisoft's marketing team came up with the idea of naming the game Assassin's Creed, which Désilets recognized fit in perfectly with the themes they had been working on, including tying into the creed of the Assassins that "nothing is true; everything is permitted".[13] The prince character was dropped, and the game focused solely on the assassin as the playable character.[13][14]

Following the 2006 E3 presentation and the name change to Assassin's Creed, the Ubisoft Montreal team grew to support the last year of the game's development, with up to 150 persons by the end of the process.[14] Added team members included those that had just finished up production on Prince of Persia: The Two Thrones, as well as former staff that had recently been let go from Gameloft, another publisher owned by Ubisoft's co-founder Michel Guillemot.[13] The Scimitar engine was completed, allowing the team to transfer their work and improve detail and art assets.[13]

According to Charles Randall, the lead AI developer for the game's combat systems, the game was initially only based on the main missions of assassinating the main targets and had no side quests. About five days before they were to have sent the final software version for mass production, they were contacted by their CEO, who said his son had played the game and found it boring and gave them a missive to add side quests. The team spent the next five days hastily rushing to add the collecting side quests to give the game more depth and ensure these were bug-free to make their mass production deadline. While a few noted bugs fell through, they had otherwise met this target.[22]

Voice acting

editOn September 28, 2006, in an interview with IGN, producer Jade Raymond confirmed that Altaïr is "a medieval hitman with a mysterious past" and that he is not a time traveller.[23] In a later interview on December 13, 2006, with IGN, Kristen Bell, who lent her voice and likeness to the game, talked about the plot. According to the interview, the plot centers on genetic memory and a corporation looking for descendants of an assassin.[24]

"It's actually really interesting to me. It's sort of based on the research that's sort of happening now, about the fact that your genes might be able to hold memory. And you could argue semantics and say it's instinct, but how does a baby bird know to eat a worm, as opposed to a cockroach, if its parents don't show it? And it's about this science company trying to, Matrix-style, go into people's brains and find out an ancestor who used to be an assassin, and sort of locate who that person is."[24]

— Kristen Bell, 2006

Actor Philip Shahbaz voices Altaïr, whose face is modelled on Francisco Randez, a model from Montréal.[25][26] Al Mualim's character is roughly based on Rashid ad-Din Sinan, who in 1191 was the leader of the Syrian branch of the Hashshashin in the Nizari Ismaili state and was nicknamed "The Old Man of the Mountain". Al Mualim was referred to as Sinan in Assassin's Creed: Altaïr's Chronicles.[27] On October 22, 2007, an IGN Australia interview with Patrice Desilets mentioned that the lead character's climbing and running were done by "Alex and Richard – the same guys from Prince of Persia".[28]

Release

editThe game was released for PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360 on November 13, 2007, in North America, November 16 in Europe, and November 21 in Australia and New Zealand.[29][30]

It was made public in April 2008 that Assassin's Creed would be sold digitally and available for pre-order through Valve's software distribution, Steam. The PC version of Assassin's Creed was released in North America on April 8, 2008. Four bonus mission types, not seen in the console versions, are included. These four missions are archer assassination, rooftop race challenge, merchant stand destruction challenge, and escort challenge. Because of these four exclusive missions that are only available on the PC, it was released and is sold under the name of Director's Cut Edition.[31]

A pirated version of the game has been in existence since late February 2008. Ubisoft purposely inserted a computer bug into the pre-release version to unpredictably crash the game and prevent completion as a security measure; however, players were able to use extra content available on the Internet to bypass it.[32][33] The pirated version of Assassin's Creed was one of the most popular titles for piracy during the first week of March 2008.[34] The presence of the bug and performance of the pirated version of the game was believed by Ubisoft to lead to "irreparable harm" for the game and resulted in low retail sales; NPD Group reports that 40,000 copies of the PC title were sold in the United States in July, while more than 700,000 copies were illegally downloaded according to Ubisoft.[32][35] In July 2008, Ubisoft sued disc manufacturer Optical Experts Manufacturing, believing the company to be the source of the leak, citing poor security procedures that allowed an employee to leave with a copy of the game.[32][35]

A digital rights management-free game version was later made by GOG.com, a digital distribution store and a subsidiary of CD Projekt and CD Projekt Red. It is available on the GOG Store and GOG Galaxy. On July 10, 2007, during Microsoft's E3 press conference, a demo was shown taking place in Jerusalem. Features that were demonstrated included improved crowd mechanics, the chase system (chasing after a target trying to flee), as well as deeper aspects of parkour. This was the first time when Altaïr could be heard speaking. It was again showcased for 20 minutes on July 11, 2007. A video showed an extended version of the E3 demo and included Altaïr trying to escape after assassinating of Talal, the slave trader.[36]

Music

editJade Raymond, the producer of Assassin's Creed, said: "For Assassin's Creed we wanted the score to capture the gruesome atmosphere of medieval warfare but also be edgy and contemporary."[37] The musical score was composed by Jesper Kyd in 2007. Six tracks were made available online to those who have purchased the game; a password was given to people to insert at the soundtrack section of the Ubisoft website.[38] The soundtrack is available from various online music stores. Several tracks are also available on Kyd's MySpace, his official website, and his YouTube channel. The released tracks have the archaic Latin chorus and dark orchestral music, while "Meditation Begins" features a kind of Saltarello with a very ominous, dark, ambient overtone with men whispering in Latin. The atmosphere in these tracks is what Jesper Kyd is known for and is effective in situ.[39]

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "City of Jerusalem" | 3:11 |

| 2. | "Flight Through Jerusalem" | 3:39 |

| 3. | "Spirit of Damascus" | 1:31 |

| 4. | "Trouble in Jerusalem" | 4:04 |

| 5. | "Acre Underworld" | 3:24 |

| 6. | "Access the Animus" | 9:34 |

| 7. | "Dunes of Death" | 1:46 |

| 8. | "Masyaf in Danger" | 3:43 |

| 9. | "Meditation Begins" | 2:47 |

| 10. | "Meditation of the Assassin" | 3:43 |

| 11. | "The Bureau" | 3:12 |

- ^ While the song "The Chosen (Assassin's Creed)" by Intwine featuring Brainpower was made contributing to the game, it was not featured in the game nor its soundtrack. Other songs used in previews and trailers, such as "Teardrop" by Massive Attack and "Lonely Soul" by UNKLE, are also not present on the soundtrack.

Reception

editCritical reception

edit| Aggregator | Score |

|---|---|

| Metacritic | (PS3) 81/100[40] (X360) 81/100[41] (PC) 79/100[42] |

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| 1Up.com | B−[43] |

| Eurogamer | 7/10 |

| Famitsu | 37/40 |

| Game Informer | 9.5/10 |

| GameSpot | 9/10 |

| GamesRadar+ | 5/5 |

| GamesTM | 4/5 |

| IGN | 7.5/10[44] |

| Official Xbox Magazine (US) | 8.5/10 |

| PlayStation: The Official Magazine | 5/5[45] |

Assassin's Creed received "generally favorable" reviews from critics according to Metacritic, a review aggregator. Famitsu awarded the Xbox 360 version of Assassin's Creed a 36 (9, 9, 9, 9) and the PlayStation 3 version a 37 (10, 8, 9, 10) out of 40, positively citing the story, presentation, and acrobatics, while criticizing the one-button combat, map layout, and camera problems.[46][47] Game Informer awarded Assassin's Creed a 9.5 out of 10, praising the control scheme, replay value, and intriguing story, and expressing frustration over the repetitive information gathering missions.[48] On The Hotlist on ESPNews, ESPN's Aaron Boulding called the game's concept of social stealth "fairly original" and added: "Visually, the developers nailed it."[49] GameTrailers praised the story (giving a 9.7 score to its story), and also cited repetitive gameplay and bad AI as somewhat stifling its potential. It wrote that "Assassin's Creed is one of those games that breaks new ground yet fails in nailing some fundamentals."[50] The game also received a 10 out of 10 from GamesRadar,[40][41] as well as from PlayStation: The Official Magazine.[45] According to GamePro, it is one of the "finest gaming experiences ever created" if one is willing to be patient due to the lack of fast-paced action.[51] Kevin VanOrd of GameSpot gave it a 9 out of 10, stating that "the greatest joy comes from the smallest details, and for every nerve-racking battle, there's a quiet moment that cuts to the game's heart and soul."[52]

While still awarding the game decent scores, several publications cited a number of significant shortcomings. Michael Donahoe of 1Up.com gave it a B− for the story concept but felt more could have been done, writing "it's apparent that these grandiose ideas may have been a little too much to master the first go-round. ... at least the groundwork is laid for a killer sequel."[43] Eurogamer stated that the gameplay "never evolves and ultimately becomes a bit boring, and quite amazingly repetitive."[53] Hyper's Darren Wells commended the game for its "great story, great graphics and intuitive controls". At the same time, he criticised it for "some missions that don't feel right on the PC and its loopy menu system."[54] Hilary Goldstein of IGN gave the game a 7.5/10 ("Good"), stating that "a bad story, repetitive gameplay elements, and poor AI lead to the downfall of one of the more promising games in recent memory." Conversely, he complimented the combat animations and the climbing mechanic, and admired how accurately Ubisoft depicted the major cities of Jerusalem, Acre, and Damascus to their real-life counterparts.[44] In Andrew P.'s mixed review for Electronic Gaming Monthly, he wrote that the game features "a challenging parkour path of escape", and while intriguing, it is "an incomplete template based on multiple other games".[55]

Awards

editAssassin's Creed won several awards at the 2006 E3. Game Critics awarded it "Best Action/Adventure Game";[56] "Best Action Game", "PS3 Game of the Show", "Best PS3 Action Game", and "Best PS3 Graphics" from IGN; "Best PS3 Game of the Show" from GameSpot and GameSpy; "Best of Show" from GameTrailers; and "Best PS3 Game" from 1UP.com. Assassin's Creed was nominated for several other awards by Xplay,[57] as well as Spike TV.[58] Assassin's Creed received multiple nominations at AIAS' 11th Annual Interactive Achievement Awards: "Adventure Game of the Year", "Outstanding Innovation in Gaming" and outstanding achievement in "Animation" (which it won), "Art Direction", "Gameplay Engineering" and "Visual Engineering".[59] It was listed by Game Informer at 143 in their list of the top 200 games of all time. It also received the editor's choice award from GameSpot.[60][61]

Sales

editSales for Assassin's Creed were said by the publisher to have "greatly outstripped" their expectations.[62] In the United Kingdom, Assassin's Creed debuted at number one, knocking Infinity Ward's Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare from the top; the majority of the debut sales were on the Xbox 360, which claimed 67% of the game's total sales.[63] The Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3 releases of Assassin's Creed each received a platinum sales award from the Entertainment and Leisure Software Publishers Association,[64] indicating sales of at least 300,000 copies per version in the United Kingdom.[65] On April 16, 2009, Ubisoft revealed that the game had sold 8 million copies.[66]

Sequels

editA prequel for the game, titled Assassin's Creed: Altaïr's Chronicles, developed by Gameloft,[67] was released on February 5, 2008, for the Nintendo DS.[68] A port of Assassin's Creed: Altaïr's Chronicles has also been released for the iPhone and the iPod Touch and Java ME on April 23, 2009, as well as for the Palm Pre.[69]

Assassin's Creed II was released in the United States and Canada on November 17, 2009, and in Europe on November 20, 2009.[70]

References

edit- ^ "Assassin's Creed (Director's Cut Edition)". IGN. Archived from the original on December 6, 2011. Retrieved January 9, 2012.

- ^ "Assassin's Creed". EB Games Australia. Archived from the original on April 8, 2008. Retrieved April 4, 2008.

- ^ "Assassin's Creed". EB Games New Zealand. Archived from the original on April 11, 2008. Retrieved April 4, 2008.

- ^ "Assassin's Creed". GAME. Archived from the original on March 12, 2008. Retrieved April 4, 2008.

- ^ Luis, Vanessa (August 29, 2016). "Why Assassin's Creed is One of the Best Action-Adventure Games of All Time". Tata CLiQ. Archived from the original on 28 September 2020. Retrieved January 28, 2018.

- ^ GamesRadar Staff (January 3, 2018). "The 10 best open-world games of all time". GamesRadar. Archived from the original on January 28, 2018. Retrieved January 28, 2018.

- ^ "Assassin's Creed Cello Trailer". Ubisoft. November 9, 2007. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved December 6, 2022 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b c d Walton, Jarred (June 2, 2008). "Assassin's Creed PC". AnandTech. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- ^ "Assassin's Creed Xbox 360 Gameplay – X06: First Demo (Off-Screen)". IGN. September 27, 2006. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- ^ "Assassin's Creed (Video Game 2007)". IMDb. Retrieved 2024-11-04.

- ^ a b c Wheeler, Greg (June 14, 2020). "Assassin's Creed – Story Recap & Review". The Review Geek. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c Dyer, Mitch (February 3, 2014). "House Of Dreams: The Ubisoft Montreal Story". IGN. Archived from the original on October 4, 2018. Retrieved October 4, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Moss, Richard (October 3, 2018). "Assassin's Creed: An oral history". Polygon. Archived from the original on October 3, 2018. Retrieved October 3, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Edge staff (March 24, 2013). "The Making of Assassin's Creed". Edge. p. 1. Archived from the original on March 27, 2013. Retrieved March 24, 2013.

- ^ CVG Staff (November 7, 2006). "Interview: Assassin's Creed". Computer and Video Games. Archived from the original on October 14, 2007. Retrieved November 3, 2008.

- ^ Doerr, Nick (November 10, 2006). "Assassin's Creed producer speaks out, we listen intently [update 1]". Archived from the original on December 25, 2008. Retrieved November 3, 2008.

- ^ a b Edge staff (March 24, 2013). "The Making of Assassin's Creed". Edge. p. 3. Archived from the original on 2013-05-30. Retrieved March 24, 2013.

- ^ Pearson, Ryan (December 13, 2007). "Assassin's Creed sales outpace expectations". NBC News. Archived from the original on March 5, 2021. Retrieved October 27, 2023.

- ^ Stanley, TL (November 5, 2007). "Ultimate marketing: Ubisoft gets its game on with Comedy, Spike ad blitz". Mediaweek. Archived from the original on November 5, 2024. Retrieved October 21, 2024 – via Gale Research.

- ^ a b c Edge staff (March 24, 2013). "The Making of Assassin's Creed". Edge. p. 2. Archived from the original on March 27, 2013. Retrieved March 24, 2013.

- ^ "Assassin's Creed - Interview de Jade Raymond sur Xbox Gazette". Archived from the original on 2018-10-05. Retrieved 2018-10-04.

- ^ Yin-Poole, Wesley (May 23, 2020). "The wild story behind why the first Assassin's Creed has side missions". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on 9 June 2020. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- ^ "IGN: Assassin's Creed Preview". IGN. September 28, 2006. Archived from the original on September 19, 2011. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ a b "IGN: IGN Exclusive Interview: Kristen Bell". IGN. December 13, 2006. Archived from the original on October 14, 2014. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ "Francisco Randez prête son visage à Altaïr". Lienmultimedia (in French). Archived from the original on February 13, 2008. Retrieved April 15, 2008.

- ^ "Francisco Randez". The Models Resource. Archived from the original on April 30, 2009. Retrieved September 15, 2009.

- ^ Barratt, Alistar (March 15, 2021). "New clues lead to new rumours about the next Assassin's Creed's setting". Millenium US. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- ^ "IGN: Assassin's Creed AU Interview: Patrice Desilets". IGN. October 22, 2007. Archived from the original on October 14, 2014. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ GameSpot Staff (October 29, 2007). "Assassin's Creed golden". GameSpot. Archived from the original on May 7, 2018. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- ^ Chiappini, Dan (November 13, 2007). "Assassin's Creed delayed in Australia and New Zealand". GameSpot. Archived from the original on May 7, 2018. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- ^ "Assassin's Creed PC: New Investigation Types – News". Spong. March 4, 2008. Archived from the original on January 2, 2009. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ a b c Sinclair, Brendan (March 6, 2008). "Ubisoft sues over Assassin's Creed leak". GameSpot. Archived from the original on February 12, 2009. Retrieved August 7, 2008.

- ^ Rossignol, Jim (March 4, 2008). "So... Assassin's Creed PC?". Rock Paper Shotgun. Archived from the original on March 7, 2008. Retrieved March 6, 2008.

- ^ Gillen, Kieron (March 5, 2008). "The Yarr-ts: Piracy Snapshot 5.3.2008". Rock Paper Shotgun. Archived from the original on March 9, 2008. Retrieved March 6, 2008.

- ^ a b Jenkins, David (August 7, 2008). "Ubisoft Files $10M Suit Over Assassin's Creed PC Leak". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on August 16, 2008. Retrieved August 7, 2008.

- ^ "Assassin's Creed Stage Demo". Ubisoft. July 2007. Archived from the original on 11 July 2018. Retrieved December 6, 2022 – via Metacritic.

- ^ McWhertor, Michael (October 16, 2007). "Assassin's Creed Score Is BAFTAstic". Kotaku. Archived from the original on July 8, 2008. Retrieved May 11, 2008.

- ^ "Soundtrack's - Assassin's Creed". Ubisoft. Archived from the original on April 16, 2008. Retrieved May 11, 2008.

- ^ "Tracksounds Now!: Assassin's Creed (Soundtrack) by Jesper Kyd". Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ a b "Assassin's Creed (ps3) reviews at Metacritic.com". GameRankings. Archived from the original on December 22, 2011. Retrieved August 15, 2009.

- ^ a b "Assassin's Creed (xbox360) reviews at Metacritic.com". GameRankings. Archived from the original on March 15, 2012. Retrieved August 15, 2009.

- ^ "Assassin's Creed Director's Cut (pc) reviews at Metacritic.com". GameRankings. Archived from the original on January 27, 2012. Retrieved August 15, 2009.

- ^ a b Donahoe, Michael (November 12, 2007). "Assassin's Creed: Review". 1Up.com. Archived from the original on 2012-06-18. Retrieved September 21, 2022.

- ^ a b Goldstein, Hilary (13 November 2007). "Assassin's Creed Review". IGN. Archived from the original on 21 April 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ a b Nelson, Randy (January 2008). "Review: Assassin's Creed". PlayStation: The Official Magazine. No. 2. Future US. pp. 76–77.

- ^ "Famitsu reviews Dragon Quest IV, Assassins Creed, Guilty Gear 2 and more". Archived from the original on April 16, 2009. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ "Assassin's Creed nabs 37/40 from Famitsu". Joystiq. November 2, 2007. Archived from the original on October 9, 2014. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ Miller, Matt (December 2007). "History with a Twist". Game Informer. No. 176. Archived from the original on November 9, 2007. Retrieved December 21, 2022.

- ^ ESPN – Easy Points – 'Tis the Season – Videogames

- ^ "GameTrailers Assassin's Creed Video Review". GameTrailers. Archived from the original on May 4, 2009. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ Melick, Todd (November 14, 2007). "Assassin's Creed review". GamePro. Archived from the original on November 10, 2007. Retrieved January 8, 2008.

- ^ VanOrd, Kevin (November 13, 2007). "Assassin's Creed Review". GameSpot. Archived from the original on July 25, 2013. Retrieved December 21, 2022.

- ^ "Assassin's Creed Review // Xbox 360 /// Eurogamer". Eurogamer.net. November 13, 2007. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ Wells, Darren (June 2008). "Assassin's Creed". Hyper (176). Next Media: 54. ISSN 1320-7458.

- ^ P., Andrew (January 2008). "Review of Assassin's Creed". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 224. p. 89.

- ^ "2006 Winners". Game Critics Awards. Archived from the original on March 22, 2008. Retrieved March 23, 2008.

- ^ "2007 X-Play Best of 2007 Award Nominations". G4. Archived from the original on March 25, 2018. Retrieved December 10, 2007.

- ^ Magrino, Tom (November 11, 2007). "Halo 3, BioShock top Spike TV noms". GameSpot. Archived from the original on February 2, 2009. Retrieved November 11, 2007.

- ^ "D.I.C.E. Awards By Video Game Details Assassin's Creed". interactive.org. Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- ^ McNamara, Andy (2009). "GameInformer". Game Informer. No. 200. Sunrise Publications. ISSN 1067-6392.

- ^ Bartol, Vladimir (18 December 2012). "Game Informer Magazine 2010 Manitowoc: for video game enthusiasts". Game Informer. ISBN 9781583946954. ISSN 1067-6392. OCLC 688210946.

- ^ "Ubisoft Announces Outstanding Sales Performance For Assassin's Creed and Raises Guidance for Fiscal 2007-08". Ubisoft. Archived from the original on December 18, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2008.

- ^ "Chart Assassination for Call of Duty - Games Industry - MCV". MCV UK. November 20, 2007. Archived from the original on October 9, 2008. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ "ELSPA Sales Awards: Platinum". Entertainment and Leisure Software Publishers Association. Archived from the original on May 15, 2009.

- ^ Caoili, Eric (November 26, 2008). "ELSPA: Wii Fit, Mario Kart Reach Diamond Status In UK". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on September 18, 2017.

- ^ "Ubisoft Unveils Assassins Creed II" (PDF). Ubisoft. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 19, 2009. Retrieved June 4, 2009.

- ^ "Assassin's Creed: Altaïr's Chronicles" Archived 2008-12-27 at the Wayback Machine. PocketGamer. Retrieved October 7, 2008.

- ^ "Nintendo lays out Q4 '07, Q1 '08 slate". GameSpot. Archived from the original on February 12, 2009. Retrieved December 29, 2007.

- ^ Starrett, Charles (April 14, 2009). "Gameloft previews Assassin's Creed for iPhone, iPod touch". iLounge. Archived from the original on April 19, 2009. Retrieved April 15, 2009.

- ^ "IGN: New Ghost Recon, Assassin's Creed 2 Coming". IGN. July 17, 2009. Archived from the original on January 25, 2009. Retrieved April 11, 2009.