An astronaut propulsion unit (or astronaut maneuvering unit) is used to move an astronaut relative to the spaceship during a spacewalk. The first astronaut propulsion unit was the Hand-Held Maneuvering Unit (HHMU) used on Gemini 4.

Models

editHand-Held Maneuvering Unit

editThe Hand-Held Maneuvering Unit was the EVA "zip" gun used by Ed White on the Gemini 4 mission in 1965. The hand-held gun held several pounds of nitrogen,[1] and allowed limited movement around the Gemini spacecraft. It was also used by astronaut Michael Collins on the Gemini 10 mission in 1966.

USAF Astronaut Maneuvering Unit

editThe United States Air Force (USAF) Astronaut Maneuvering Unit (AMU) was designed by the U.S. Air Force, which was planning to use the Gemini spacecraft as part of the Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL). The AMU was a backpack using hydrogen peroxide as the fuel. The total delta-v capability of the AMU was about 250 feet per second (76.2 meters per second), roughly three times that of the MMU. The astronaut would strap on the AMU like a backpack, and maneuver around using two hand controllers like that of the later MMU. Because of the fuel, which came out as a hot gas, the astronaut's suit had to be modified with the addition of woven metal "pants" made of Chromel-R metal cloth. The AMU was carried aboard the Gemini 9 mission, but was not tested because the astronaut, Eugene Cernan, had difficulty maneuvering from the Gemini cabin to the AMU storage place, at the back of the spacecraft, and overheated, causing his helmet faceplate to fog up. The AMU was also meant to be launched and flown on-board Gemini 12, and to fly untethered from the Gemini spacecraft, but was scrubbed two months before the mission.[2] NASA chief astronaut Deke Slayton later speculated in his autobiography that the AMU may have been developed for the MOL program because the Air Force "thought they might have the chance to inspect somebody else's satellites."[3]

Automatically Stabilized Maneuvering Unit (ASMU)

editIn 1973, the Automatically Stabilized Maneuvering Unit (ASMU) was test-flown aboard Skylab during the Skylab 3[4] and 4 missions. Tested inside of the orbiting laboratory, it used nitrogen gas allowing both unsuited and suited testing of the unit. The Skylab AMU was the closest to the Shuttle MMU, but was not used outside the spacecraft because the EVAs were conducted with the astronauts attached to life support umbilicals, and to prevent damage to the delicate solar arrays on the Apollo Telescope Mount.

Foot Controlled Maneuvering Unit (FCMU)

editThe Foot Controlled Maneuvering Unit was tested within Skylab. The purpose of it was to free the astronaut's hands. It was propelled by cold, high-pressured nitrogen gas located in a tank on the back.[5] It was tested both suited and unsuited.

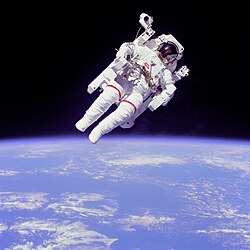

Manned Maneuvering Unit

editThe Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU) is a propulsion backpack which was used by NASA astronauts on three space shuttle missions in 1984. The MMU allowed the astronauts to perform untethered EVA spacewalks at a distance from the shuttle. The MMU was used in practice to retrieve a pair of faulty communications satellites, Westar VI and Palapa B2. Following the third mission the unit was retired from use.

Soviet SPK

editThe Soviet Union also used a cosmonaut propulsion system on flights to the space station Mir. The SPK (or UMK, UPMK[6]) was larger than the Space Shuttle MMU, contained oxygen instead of nitrogen and was attached to a safety tether. Despite the tether, the SPK allowed the cosmonaut, wearing the self-contained Orlan spacesuit, to "fly around" the orbiting complex, allowing access to areas nearly impossible to access otherwise. Though tested on Mir in 1990, the cosmonauts preferred using the Strela crane (equivalent to the Mobile Servicing System). The SPK, which was left attached to the outside to the Kvant-2 module, was destroyed when Mir re-entered the atmosphere after decommissioning.

The 21KS[6] system is a completely new design for Orlan-DMA spacesuit not using a safety tether, but air jet engines. This system was similar to MMU. It was automatically stabilized, used 6 degrees of freedom, weighed less than 180 kg, had a delta-v of 30 m/s, practical speed of 1 m/s, and an emergency mode that allows for rotational acceleration of 8°/s^2.[7]

SAFER

editThe Simplified Aid For EVA Rescue (SAFER) is a smaller backpack propulsion system intended as a safety device during space walks. It contains 1.4 kg of gaseous nitrogen, which provides much less delta-v capability than the MMU, roughly 10 feet per second (3 meters per second). However SAFER is less complex, less expensive and simpler to use than the MMU, and the limited delta-v is sufficient for the intended rescue-only task. Other Crew Self Rescue (CSR) devices of which prototypes have been developed include an inflatable pole, a telescoping pole, a bi-stem pole and a bola-type lasso device (astrorope) the drifting astronaut could throw to hook to the space station.

References

edit- ^ Kranz, Gene (2000). Failure Is Not an Option. Berkley Books. p. 135. ISBN 0-425-17987-7.

- ^ Kenneth S. Thomas & Harold J. McMann (2006). US Spacesuits. Chichester, UK: Praxis Publishing Ltd. p. 32. ISBN 0-387-27919-9.

- ^ Slayton, Donald K. "Deke"; Cassutt, Michael (1994). Deke! U.S. Manned Space: From Mercury to the Shuttle (1st ed.). New York: Forge (St. Martin's Press). p. 174. ISBN 0-312-85503-6. LCCN 94-2463. OCLC 29845663.

- ^ Leland F. Belew, ed. (1977). "SP-400 Skylab, Our First Space Station, Chapter 7 -- The Second Manned Period". George C. Marshall Space Flight Center.

- ^ Millbrooke, Anne (1998). "From Engineering Science To Big Science, Chapter 13 -- More Favored than the Birds: The Manned Maneuvering Unit in Space".

- ^ a b Isaac Abramov & Ingemar Skoog (2003). Russian Spacesuits. Chichester, UK: Praxis Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-85233-732-X.

- ^ Igor Afanasiev & Dmitry Vorontzov (2010). "Cosmonaut's Personal Transport". Vokrug Sveta. Moscow. Retrieved September 29, 2013.

Further reading

editExternal links

edit- "More Favored than the Birds": The Manned Maneuvering Unit in Space

- NASA Manned maneuvering unit: User's guide - 1978 (PDF document)

- Assessment of the NASA Manned Maneuvering Unit - 1988 (PDF document)

- Astronautix SPK