AV nodal reentrant tachycardia

AV-nodal reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT) is a type of abnormal fast heart rhythm. It is a type of supraventricular tachycardia (SVT), meaning that it originates from a location within the heart above the bundle of His. AV nodal reentrant tachycardia is the most common regular supraventricular tachycardia. It is more common in women than men (approximately 75% of cases occur in females). The main symptom is palpitations. Treatment may be with specific physical maneuvers, medications, or, rarely, synchronized cardioversion. Frequent attacks may require radiofrequency ablation, in which the abnormally conducting tissue in the heart is destroyed.

| AV-nodal reentrant tachycardia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Atrioventricular-nodal reentrant tachycardia |

| |

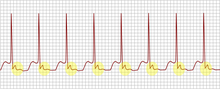

| An example of an ECG tracing typical of uncommon AV nodal reentrant tachycardia. Highlighted in yellow is the P wave that falls after the QRS complex. | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

| Symptoms | Palpitations, chest tightness, neck pulsation |

| Diagnostic method | electrocardiogram, electrophysiological study |

| Differential diagnosis | Atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia, focal atrial tachycardia, junctional ectopic tachycardia |

| Treatment | vagal manoeuvres, adenosine, ablation |

| Medication | adenosine, calcium channel antagonists, beta blockers, flecainide |

AVNRT occurs when a reentrant circuit forms within or just next to the atrioventricular node. The circuit usually involves two anatomical pathways: the fast pathway and the slow pathway, which are both in the right atrium. The slow pathway (which is usually targeted for ablation) is located inferior and slightly posterior to the AV node, often following the anterior margin of the coronary sinus. The fast pathway is usually located just superior and posterior to the AV node. These pathways are formed from tissue that behaves very much like the AV node, and some authors regard them as part of the AV node.

The fast and slow pathways should not be confused with the accessory pathways that give rise to Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome (WPW syndrome) or atrioventricular reciprocating tachycardia (AVRT). In AVNRT, the fast and slow pathways are located within the right atrium close to or within the AV node and exhibit electrophysiologic properties similar to AV nodal tissue. Accessory pathways that give rise to WPW syndrome and AVRT are located in the atrioventricular valvular rings. They provide a direct connection between the atria and ventricles, and have electrophysiologic properties similar to muscular heart tissue of the heart's ventricles.

Signs and symptoms

editThe main symptom of AVNRT is the sudden development of rapid regular palpitations.[1] These palpitations may be associated with a fluttering sensation in the neck, caused by near-simultaneous contraction of the atria and ventricles against a closed tricuspid valve leading to the pressure or atrial contraction being transmitted backwards into the venous system.[2] The rapid heart rate may lead to feelings of anxiety, and may therefore be mistaken for panic attacks.[2] In some cases, the onset of the fast heart is associated with a brief drop in blood pressure. When this happens, someone may experience dizziness or rarely lose consciousness (faint).[3] Someone with underlying coronary artery disease (narrowing of the arteries of the heart by atherosclerosis) who has a very rapid heart rate may experience chest pain similar to angina; this pain is band- or pressure-like around the chest and often radiates to the left arm and angle of the left jaw.[3]

Symptoms often occur without any specific trigger, although some find that their palpitations often occur after lifting heavy items or bending forwards.[1] The onset of palpitations is sudden, with the acceleration of the heart rate occurring within a single beat, and may be preceded by a feeling of the heart skipping a beat. The heart may continue to race for minutes or hours, but the eventual termination of the arrhythmia is as rapid as its onset.[1]

During AVNRT the heart rate is typically between 140 and 280 beats per minute.[3] Close inspection of the neck may reveal pulsation of the jugular vein in the form of "cannon A-waves" as the right atrium contracts against a closed tricuspid valve.[2]

Mechanisms

editThe fundamental mechanism of AVNRT is a presence of a dual atrioventricular node physiology (present in half of the population), which acts as a re-entrant circuit within the atrioventricular node.[4] This can take several forms. "Typical", "common", or "slow-fast" AVNRT uses the slow AV nodal pathway to conduct towards the ventricle (the anterograde limb of the circuit) and the fast AV nodal pathway to conduct to the atria (the retrograde limb). The re-entrant circuit can be reversed such that the fast AV nodal pathway is the anterograde limb and the slow AV nodal pathway is the retrograde limb, referred to as "atypical", "uncommon", or "fast-slow" AVNRT. Atypical AVNRT may also use the slow AV nodal pathway as the anterograde limb and left atrial fibres that approach the AV node from the left side of the inter-atrial septum as the retrograde limb, and is sometimes referred to as "slow-slow" AVNRT.[5]

Typical AVNRT

editIn typical AVNRT, the anterograde conduction is via the slow pathway and the retrograde conduction is via the fast pathway ("slow-fast" AVNRT).[citation needed]

Because the retrograde conduction is via the fast pathway, stimulation of the atria (which produces the inverted P wave) occurs very soon after stimulation of the ventricles (which causes the QRS complex). As a result, the time from the QRS complex to the P wave (the RP interval) is short, less than 50% of the time between consecutive QRS complexes. The RP interval is often so short that the inverted P waves may not be seen on the surface electrocardiogram (ECG) as they are buried within or immediately after the QRS complexes, appearing as a "pseudo R prime" wave in lead V1 or a "pseudo S" wave in the inferior leads.[6]

Atypical AVNRT

editIn atypical AVNRT, the anterograde conduction is via the fast pathway and the retrograde conduction is via the slow pathway ("fast-slow" AVNRT).[6]

Multiple slow pathways can exist so that both anterograde and retrograde conduction are over slow pathways. ("slow-slow" AVNRT).Because the retrograde conduction is via the slow pathway, stimulation of the atria will be delayed by the slow conduction tissue and will typically produce an inverted P wave that falls after the QRS complex on the surface ECG.[citation needed]

Diagnosis

editIf the symptoms are present while the person is receiving medical care (e.g., in an emergency department), an ECG may show typical changes that confirm the diagnosis i.e., QRS duration <120 ms, unless a heart block is suspected.[7] If the palpitations are recurrent, a doctor may request a Holter monitor (portable, wearable ECG recorder). Again, this will show the diagnosis if the recorder is attached at the time of the symptoms. In rare cases, disabling but infrequent episodes of palpitations may require the insertion of a small device under the skin that continuously record heart activity (an implantable loop recorder). All these ECG-based technologies also enable the distinction between AVNRT and other abnormal fast heart rhythms such as atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, sinus tachycardia, ventricular tachycardia and tachyarrhythmias related to Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, all of which may have symptoms that are similar to AVNRT.[citation needed]

Blood tests commonly performed in people with palpitations are:[citation needed]

- thyroid function tests (TFTs) – an overactive thyroid increases the risk of AVNRT

- electrolytes – disturbances in potassium, calcium and magnesium may predispose to AVNRT

- cardiac markers – if there is a concern that myocardial infarction (heart attack) has occurred either as a cause or as a result of the AVNRT; this is usually only the case if the patient has experienced chest pain

Treatment

editTreatments for AVNRT aim to terminate episodes of tachycardia, and to prevent further episodes from occurring in the future. These treatments include physical manoeuvres, medication, and invasive procedures such as ablation.[8]

Arrhythmia termination

editAn episode of supraventricular tachycardia due to AVNRT can be terminated by any action that transiently blocks the AV node. Some of those with AVNRT may be able to stop their attack by using physical manoeuvres that increase the activity of the vagus nerve on the heart, specifically on the atrioventricular node. These manoeuvres include carotid sinus massage (pressure on the carotid sinus in the neck) and the Valsalva manoeuvre (increasing the pressure in the chest by attempting to exhale against a closed airway by bearing down or holding one's breath).[9]

Medications that slow or briefly halt electrical conduction through the AV node can terminate AVNRT, including adenosine, beta blockers, or non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (such as verapamil or diltiazem).[9] Both adenosine and beta blockers may cause tightening of the airways, and are therefore used with caution in people who are known to have asthma. Less commonly used drugs for this purpose include antiarrhythmic drugs such as flecainide or amiodarone.[8]

If the fast heart rate is poorly tolerated (e.g. the development of heart failure symptoms, low blood pressure or coma) then AVNRT can be terminated electrically using a cardioversion. In this procedure, after administering a strong sedative or general anaesthetic, an electric shock is applied to the heart to restore a normal rhythm.[8]

Arrhythmia prevention

editWhile preventative treatment may be very helpful at stopping the unpleasant symptoms associated with AVNRT, as this arrhythmia is a benign condition, preventative treatment is not essential.[8] Some of those who choose not to have further treatment will eventually become asymptomatic.[8] Those who wish to have further treatment can choose to take long term antiarrhythmic medication. The first line drugs are calcium channel antagonists and beta blockers, with second line agents including flecainide, amiodarone, and occasionally digoxin. These drugs are moderately effective at preventing further episodes but need to be taken long term.[8]

Alternatively, an invasive procedure called an electrophysiology (EP) study and catheter ablation can be used to confirm the diagnosis and potentially offer a cure. This procedure involves introducing wires or catheters into the heart through a vein in the leg.[2] The tip of one of these catheters can be used to heat or freeze the slow pathway of the AV node, destroying its ability to conduct electrical impulses, and preventing AVNRT.[10] The risks and benefits are weighed up before this is performed. Catheter ablation of the slow pathway, if successfully carried out, can potentially cure AVNRT with success rates of >95%, balanced against a small risk of complications including damaging the AV node and subsequently requiring a pacemaker.[8]

References

edit- ^ a b c Rosero, Spencer (2015), "A Brief Overview of Supraventricular Tachycardias", in Huang, MD, David T.; Prinzi, MD, Travis (eds.), Clinical Cardiac Electrophysiology in Clinical Practice, In Clinical Practice, Springer London, pp. 37–53, doi:10.1007/978-1-4471-5433-4_3, ISBN 978-1-4471-5432-7

- ^ a b c d Ayala-Paredes, Félix; Roux, Jean-Francois; Verdu, Mariano Badra (2014), Kibos, Ambrose S.; Knight, Bradley P.; Essebag, Vidal; Fishberger, Steven B. (eds.), "AVNRT Ablation: Significance of Anatomic Findings and Nodal Physiology", Cardiac Arrhythmias, Springer London, pp. 387–400, doi:10.1007/978-1-4471-5316-0_30, ISBN 978-1-4471-5315-3

- ^ a b c Hafeez, Yamama; Armstrong, Tyler J. (2019), "Atrioventricular Nodal Reentry Tachycardia (AVNRT)", StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29763111, retrieved 2019-08-15

- ^ "Dual Atrioventricular Nodal Physiology - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2022-11-14.

- ^ "Atrioventricular Nodal Reentrant Tachycardia (AVNRT)". 2009-09-30.

- ^ a b Shen, Sharon; Knight, Bradley P. (2014), Kibos, Ambrose S.; Knight, Bradley P.; Essebag, Vidal; Fishberger, Steven B. (eds.), "How to Differentiate Between AVRT, AT, AVNRT, and Junctional Tachycardia Using the Baseline ECG and Intracardiac Tracings", Cardiac Arrhythmias, Springer London, pp. 199–208, doi:10.1007/978-1-4471-5316-0_15, ISBN 978-1-4471-5315-3

- ^ Demosthenes G Katritsis; A John Camm (2010). "Atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia". Circulation. 122 (8): 831–40. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.936591. PMID 20733110.

- ^ a b c d e f g Page, Richard L.; Joglar, José A.; Caldwell, Mary A.; Calkins, Hugh; Conti, Jamie B.; Deal, Barbara J.; Estes, N. A. Mark; Field, Michael E.; Goldberger, Zachary D. (May 2016). "2015 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline for the Management of Adult Patients With Supraventricular Tachycardia: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 67 (13): e27–e115. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.08.856. ISSN 1558-3597. PMID 26409259.

- ^ a b Brubaker, Sarah; Long, Brit; Koyfman, Alex (February 2018). "Alternative Treatment Options for Atrioventricular-Nodal-Reentry Tachycardia: An Emergency Medicine Review". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 54 (2): 198–206. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2017.10.003. ISSN 0736-4679. PMID 29239759.

- ^ Kumar, Darpan S.; Dewland, Thomas A.; Balaji, Seshadri; Henrikson, Charles A. (May 2017). "How to Approach Difficult Cases of AVNRT". Current Treatment Options in Cardiovascular Medicine. 19 (5): 34. doi:10.1007/s11936-017-0531-9. ISSN 1092-8464. PMID 28374333. S2CID 21354961.