The Australian flatback sea turtle (Natator depressus)[4] is a species of sea turtle in the family Cheloniidae. The species is endemic to the sandy beaches and shallow coastal waters of the Australian continental shelf. This turtle gets its common name from the fact that its shell has a flattened or lower dome than the other sea turtles. It can be olive green to grey with a cream underside. It averages from 76 to 96 cm (30 to 38 in) in carapace length and can weigh from 70 to 90 kg (150 to 200 lb). The hatchlings, when emerging from nests, are larger than other sea turtle hatchlings when they hatch.

| Flatback sea turtle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nesting on Great Keppel Island off Queensland Coast, Australia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Superfamily: | Chelonioidea |

| Family: | Cheloniidae |

| Subfamily: | Cheloniinae |

| Genus: | Natator McCulloch, 1908 |

| Species: | N. depressus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Natator depressus (Garman, 1880)

| |

| |

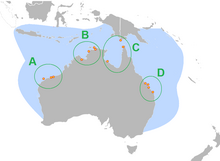

| Distribution map and nesting beaches of flatback sea turtle | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

| |

The flatback turtle is listed by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species as data deficient, meaning there is insufficient scientific information to determine its conservation status at this time.[1] It was previously listed as vulnerable in 1994.[5] It is not as threatened as other sea turtles due to its small dispersal range.[6] This animal can be 31 to 37 inches long and about 100 kg in weight

Taxonomy

editThe flatback sea turtle was originally described as Chelonia depressa in 1880 by American herpetologist Samuel Garman. The genus Natator (meaning "swimmer") was created in 1908 by Australian ichthyologist Allan Riverstone McCulloch, and in the same scientific paper he described what he thought to be a new species, Natator tessellatus, thereby creating a junior synonym. In 1988 Swiss paleontologist Rainer Zangerl assigned the flatback sea turtle to the genus Natator as the new combination Natator depressus. Because Chelonia is feminine, and Natator is masculine, the specific name was changed from depressa to depressus.

Description

editThe flatback turtle is a sea turtle that can be recognized by its smooth flat-domed shell, or carapace, which has upturned edges along the sides. It has the coloration of olive green or a mixture of grey and green. This matches the coloration of its head. The underside, also called the plastron, has a much lighter coloration of a pale yellow. The flatback sea turtle has an average carapace length ranging from 76 to 96 cm (30 to 38 in), and weighs from 70 to 90 kg (150 to 200 lb) on average.[6] Very large specimens are reported to weigh up to 350 kg (770 lb).[7] The females of this species are larger than the males in adulthood and also have been found to have longer tails than their male counterparts.[6]

Features of this sea turtle which help contribute to its recognition are the single pair of prefrontal scales on the head, and the four pairs of costal scutes on the carapace.[8] Another unique feature of this species of sea turtle is the fact that its carapace is found to be much thinner than other sea turtle carapaces.[6] This feature causes the shell to crack under the smallest pressures.[6]

The skull superficially resembles that of the olive ridley but details of the braincase most closely resemble those found in the green sea turtle.[9]

Distribution and habitat

editThe flatback sea turtle has the smallest range of the seven sea turtles. It is found in the continental shelf and coastal waters of tropic regions. It does not travel long distances in the open ocean for migrations like other sea turtles. It can typically be found in waters of 60 m (200 ft) or less in depth.[10] It does not have a global distribution like the other sea turtles. The flatback sea turtle can be found along the coastal waters of Northern Australia, the Tropic of Capricorn, and the coastal areas of Papua New Guinea. Its distribution within Australia is in the areas of eastern Queensland, Torres Strait and Gulf of Carpentaria, Northern Territory, and Western Australia.[11]

The distribution of nesting sites can be found across Queensland, the Northern Territory, and Western Australia, with the greatest concentration found in Queensland, in the Gulf of Carpentaria.[10] Within Queensland, the nesting sites can be found from the south in Bundaberg to the Torres Strait in the north.[11] The main nesting sites in this range are the southern Great Barrier Reef, Wild Duck, and Curtis Island.[11] The Torres Strait contains the major nesting sites for these turtles. Within the Northern Territory, nesting sites are more widely dispersed in this area with a wide variety of beach types on this coastline.[11] In the Western Australia area, the important nesting sites found have been the Kimberley Region, Cape Dommett, and the Lacrosse Island.[11]

The flatback sea turtle lives in the shallow, soft-bottomed tropical and subtropical waters. This turtle sticks to the continental shelf of Australia and can be found in grassy areas, bays, lagoons, estuaries, and any place with a soft-bottomed sea bed.[5][12] The habitats that females prefer for nesting sites are sandy beaches in tropical and subtropical areas.[11] They prefer beaches where the sand temperature can be in the range of 29 to 33 °C (84 to 91 °F) at nest depth, which are the temperatures that help determine the hatchling's sex.[11]

Life history

editEarly life

editThe hatchlings begin to leave the nests during the beginning of December, and the clutches will continue to hatch until late March.[13] The peak of hatchling emergence can be seen during February.[13] A flatback sea turtle hatchling is larger than other sea turtle hatchlings with its carapace length averaging 60 mm (2.4 in).[6] Its large size helps protect it from some of the predators after hatching, and allows it to also be a stronger swimmer.[6] The hatchlings tend to stay close to shore and lack the pelagic phase of other sea turtles.[6][11] The hatchlings will feed on the macroplankton present in their surface-dwelling environment.

Reproduction

editA flatback sea turtle is sexually mature anywhere between 7–50 years of age, and an adult female will nest every two to three years.[6][12] Mating occurs while the male and female are out at sea; therefore, the males will never return to shore after they hatch.[12] The flatback nesting sites can only be found along the coast of Australia within the slopes of the dunes.[8] A female will return to the same beach for her subsequent clutches within the same nesting season. She will return for other nesting seasons, as well.[13] Depending on the area of the nesting site, the nesting season can go from November to January or can last the entire year.[8] Females are able to lay up to four times throughout the nesting season, and the intervals between nesting can be 13–18 days.[8] While using her front flippers to dig, the female will clear away the dry sand located at the top.[12] After she clears the sand, the female will create an egg chamber using her back flippers.[12] After she has laid her eggs, she will then cover the nest again using her back flippers, while also tossing sand back with her front flippers.[12]

The number of eggs in a flatback sea turtle's clutch are fewer than other sea turtles.[6] It will have an average of 50 eggs laid each time in a clutch, while other sea turtles may lay up to 100-150 eggs in a clutch.[6][8] The eggs are about 55 mm (2.2 in) long within these clutches.[6] The sex of the flatback turtle hatchling is determined by the temperature of the sand that the egg is in.[11] If the temperature is below 29 °C (84 °F), the hatchling will be a male, and if the temperature is above this 29 °C it will be female.[11]

Ecology

editDiet

editThe flatback sea turtle is an omnivorous species, but predominantly eats a carnivorous diet. It feeds mostly on the prey found within the shallow waters where it swims.[6] It has been found to feed on soft corals, sea cucumbers, shrimp, jellyfish, mollusks, and other invertebrates.[6][8][12] It will also occasionally feed on seagrasses, even though it rarely feeds on vegetation.[6][12]

Predators

editThe flatback sea turtle is preyed upon by both terrestrial and aquatic organisms. The terrestrial predators it must face are dingos, invasive red foxes, feral dogs, and feral pigs.[8] Known predators of adults of this species are sharks and saltwater crocodiles.[6][11][14] The hatchlings also face predation from crabs, sea birds, and juvenile saltwater crocodiles on their journey to the waters.[11] Once in the water, the hatchlings can be preyed upon by big fish and even sharks.[11] Due to their large size when they are born and their strong swimming skills, the likelihood of capture is lowered.[6]

Conservation

editStatus

editOn the International Union for the Conservation of Nature or the IUCN's official website the flatback sea turtle is listed as data deficient.[15] However, the flatback sea turtle is listed as vulnerable nationally in Australia.[5] It is the least endangered of all of the sea turtles.[6] Unlike other sea turtles, there is not a big human demand for the meat of the flatback sea turtle.[6] It does not swim far from shore; thus, it does not get caught in nets as often as other sea turtles.[6] These reasons can contribute to why it is not in more danger of extinction.

Threats

editAll marine turtles are faced with threats such as habitat loss, the wildlife trade, collection of eggs, collection of meat, by-catch, pollution, and climate change.[8] The flatback sea turtle is specifically threatened by the direct harvest of eggs and meat by the indigenous people of Australia for traditional hunting.[10][11] These people are given the right to harvest by the government, but only if for non-commercial purposes.[11] Another threat is the destruction of nesting beaches due to coastal development and the destruction of feeding sites at coral reefs and the shallow areas near the shore.[10] Camping on these beaches compacts the sand and contributes to dune erosion,[11] and the wheel ruts caused by vehicles driving on the beaches can trap the hatchlings on their journey to the sea.[11] Coastal development contributes to barriers that make it difficult or impossible for adult turtles to reach nesting and feeding sites.[11] The flatback sea turtle also falls prey to incidental capture. It is caught by fishermen, particularly by trawling, gillnet fishing, ghost nets, and crab pots.[11] Lastly, pollution is a concern for this creature.[10] Pollution can affect the timing of egg laying, how it chooses its nesting site, how hatchlings find the sea after emerging, and how adult turtles find the beaches.[11]

Historically, climate change was thought to be an influential factor affecting the success of flatback sea turtle development; however, based on recent research performed on a select group of turtles, this was found to be untrue. Researchers have studied whether increased nest temperatures would be detrimental to embryos, whether through embryo death or negatively adapted phenotypes.[16] However, the increased nest temperature did not reduce the success of the hatchlings or the hatchling body size, but it did accelerate the development of the embryo.[16] It was also discovered that there was a high "pivotal sex-determining temperature" in that specific flatback population, which shows that some populations may had adapted to maintain large number of hatchlings of both sexes even under the effects of climate change.[16]

Conservation methods

editIn 2003, a recovery plan was set in place nationally to help this species along with other sea turtles. This plan aims to reduce mortality rates through actions within commercial fisheries and to maintain a sustainable harvest by Indigenous people. Monitoring programs are being developed and integrated, along with managing factors that affect the reproductive success of this species. In Kakadu National Park, a monitoring program has already been set up for this species. This species' critical habitat is being identified for protection. There are also efforts to enhance the spread of information about the flatback sea turtle as well as cooperation and actions internationally.[5]

There is an important turtle rookery on Avoid Island, in the Flat Isles of the Northumberland Islands group, which is a nature refuge owned by the Queensland Trust for Nature since 2006. There has been a monitoring program in place since 2013, and researchers use the facilities to collect data for various projects about the species.[17][18][19]

References

edit- ^ a b Red List Standards & Petitions Subcommittee (2022) [errata version of 1996 assessment]. "Natator depressus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996: e.T14363A210612474. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ Species Natator depressus at The Reptile Database

- ^ Limpus, Colin J. (1971). "The Flatback Turtle, Chelonia depressa Garman in Southeast Queensland, Australia". Herpetologica 27 (4): 431–446.

- ^ a b c d Taylor, Robert (May 2006). "Flatback Turtle Natator depressus" (PDF). Threatened Species of the Northern Territory. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t "Natator depressus (Flatback Turtle)". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ Hoagland, Porter; Steele, John H.; Thorpe, Steve A.; Turekian, Karl K. (2010). Marine Policy & Economics. Academic Press. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-08-096481-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Flatback turtle". wwf.panda.org. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ Chatterji, RM; Hutchinson, MN; Jones, MEH (2021). "Redescription of the skull of the Australian flatback sea turtle, Natator depressus, provides new morphological evidence for phylogenetic relationships among sea turtles(Chelonioidea)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 191 (4): 1090–1113. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa071.

- ^ a b c d e "Flatback Turtle". SEE Turtles. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Environment, jurisdiction=Commonwealth of Australia; corporateName=Department of the. "Natator depressus — Flatback Turtle". www.environment.gov.au. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h "Flatback Turtle - Natator depressus - Details - Encyclopedia of Life". Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ a b c Limpus, Colin (November 2007). "A Biolological Review of Australian Marine Turtles. 5. Flatback Turtle Natator depressus (Garman)" (PDF). The State of Queensland. Environmental Protection Agency.

- ^ Michael R. Heithaus, Aaron J. Wirsing, Jordan A. Thomson, Derek A. Burkholder (2008). "A review of lethal and non-lethal effects of predators on adult marine turtles" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology (356). Elsevier: 43–51.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pendoley, Kellie L.; Bell, Catherine D.; McCracken, Rebecca; Ball, Kirsten R.; Sherborne, Jarrad; Oates, Jessica E.; Becker, Patrick; Vitenbergs, Anna; Whittock, Paul A. (28 February 2014). "Reproductive biology of the flatback turtle Natator depressus in Western Australia". Endangered Species Research. 23 (2): 115–123. doi:10.3354/esr00569. ISSN 1863-5407.

- ^ a b c Howard, Robert; Bell, Ian; Pike, David A. (1 October 2015). "Tropical flatback turtle (Natator depressus) embryos are resilient to the heat of climate change". Journal of Experimental Biology. 218 (20): 3330–3335. doi:10.1242/jeb.118778. ISSN 0022-0949. PMID 26347558.

- ^ "Avoid Island". Queensland Trust For Nature. 2 September 2021. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ Parsons, Angel (27 February 2022). "Turtle hatching season underway on Avoid Island, an 'island ark' for vulnerable species". ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation). Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ "Vital turtle nesting site Avoid Island chosen as climate change refuge". Great Barrier Reef Foundation. 4 May 2021. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

External links

editFurther reading

edit- Cogger HG (2014). Reptiles and Amphibians of Australia, Seventh Edition. Clayton, Victoria, Australia: CSIRO Publishing. xxx + 1,033 pp. ISBN 978-0643100350.

- Garman S (1880). "On certain Species of Chelonioidæ". Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoölogy at Harvard College, in Cambridge 6: 123–126. (Chelonia depressa, new species, pp. 124–125).

- McCulloch AR (1908). "A New Genus and Species of Turtle, from North Australia". Records of the Australian Museum 7: 126-128 + Plates XXVI-XXVII. (Natator, new genus, pp. 126–127; N. tessellatus, new species, pp. 127–128).

- Wilson, Steve; Swan, Gerry (2013). A Complete Guide to Reptiles of Australia, Fourth Edition. Sydney: New Holland Publishers. 522 pp. ISBN 978-1921517280.

- Zangerl R, Hendrickson LP, Hendrickson JR (1988). "A redescription of the Australian Flatback Sea Turtle Natator depressus ". Bishop Mus. Bull. Zool. 1: 1–69. (Natator depressus, new combination).