The Archdiocese of Chicago (Latin: Archidiœcesis Chicagiensis) is a Latin Church ecclesiastical jurisdiction, an archdiocese of the Catholic Church located in Northeastern Illinois, in the United States. The Vatican erected it as a diocese in 1843 and elevated it to an archdiocese in 1880. Chicago is the see city for the archdiocese.

Archdiocese of Chicago Archidiœcesis Chicagiensis | |

|---|---|

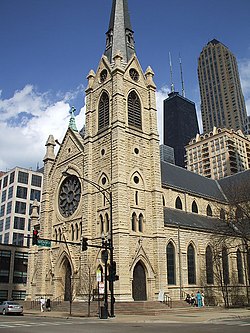

Holy Name Cathedral | |

Coat of arms | |

Flag | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| Territory | Counties of Cook and Lake |

| Ecclesiastical province | Chicago |

| Statistics | |

| Area | 1,411 sq mi (3,650 km2) |

| Population - Total - Catholics | (as of 2017) 5.94 million 2,079,000[1] (35%) |

| Parishes | 216[1] (As of 1/2024) |

| Schools | 154 archdiocesan-run[1] 34 non-archdiocesan-run[1] |

| Information | |

| Denomination | Catholic Church |

| Sui iuris church | Latin Church |

| Rite | Roman Rite |

| Established | November 28, 1843 |

| Cathedral | Holy Name Cathedral |

| Patron saint | Immaculate Conception[citation needed] |

| Secular priests | 672[1] |

| Current leadership | |

| Pope | Francis |

| Archbishop | Blase J. Cupich[2] |

| Auxiliary Bishops | |

| Vicar General | Robert Gerald Casey[3] |

| Bishops emeritus | |

| Map | |

| |

| Website | |

| archchicago.org | |

As of November 2024, Cardinal Blase Cupich is the archbishop of Chicago. The cathedral parish for the archdiocese, Holy Name Cathedral, is in the Near North Side area of Chicago.

The archdiocese serves over 2 million Catholics in Cook and Lake counties, an area of 1,411 square miles (3,650 km2). The archdiocese is divided into six vicariates and 31 deaneries. An episcopal vicar administers each vicariate. The archdiocese is the metropolitan see of the Province of Chicago. Its suffragan dioceses are the other Catholic dioceses in Illinois: Belleville, Joliet, Peoria, Rockford, and Springfield.

Cardinal Joseph Bernardin, archbishop of Chicago from 1982 to 1996, was arguably one of the most prominent figures in the American Catholic church in the post-Vatican II era, rallying progressives with his "seamless garment ethic" and his ecumenical initiatives.[4]

History

edit1600 to 1800

editThe first Catholic presence in present-day Illinois was that of a French Jesuit missionary, Reverend Jacques Marquette, who landed at the mouth of the Chicago River on December 4, 1674. A cabin he built for the winter became the first European settlement in the area. Marquette published his survey of the new territories and soon more French missionaries and settlers arrived.[5]

In 1696, a French Jesuit, Reverend Jacques Gravier, founded the Illinois mission among the Illinois, Miami, Kaskaskia and others of the Illiniwek confederacy in the Mississippi River and Illinois River valleys.[6] During this period, the French-Canadian and Native American Catholics in the region were under the jurisdiction of the bishop of the Diocese of Quebec in New France.

With the end of the French and Indian War in 1763, the British took control of Illinois. Their rule ended after the American Revolution in 1783 when the British ceded Illinois and other Midwestern territories to the new United States.[7] In 1795, the Potawatomi nation signed the Treaty of Greenville that ended the Northwest Indian War, ceding to the United States its land at the mouth of the Chicago River.[8]

1800 to 1840

editIn 1804, Pope Pius VI erected the Diocese of Baltimore, covering the entire United States. In 1822, Alexander Beaubien became the first person to be baptized as a Catholic in Chicago.[9] By 1826, the Vatican had created the Diocese of St. Louis, covering Illinois and other areas of the American Midwest.[10]

In 1833, Jesuit missionaries in Chicago wrote to Bishop Joseph Rosati of St. Louis, pleading for a priest to serve the 100 Catholics in the city. In response, Rosati appointed Reverend John Saint Cyr. a French priest, as the first resident priest in Chicago. Saint Cyr celebrated his first mass in a log cabin on Lake Street in 1833.[9] At a cost of $400, Saint Cyr constructed St. Mary, a small wooden church near Lake and State Streets. The first Catholic church in the city, it was dedicated in 1833.[11] The next year, Bishop Simon Bruté of the new Diocese of Vincennes in Indiana, visited Chicago. He found only one priest serving over 400 Catholics. Brulé asked permission from Rosati to send several priests from Vincennes to Chicago.

In 1837, Saint Cyr retired as pastor of St. Mary and was replaced by Reverend James O'Meara. He moved St. Mary to another wooden structure at Wabash Avenue and Madison Street. When O'Meara left Chicago, Saint Palais demolished the wooden church and replaced it with a brick structure.[12]

1840 to 1850

editPope Gregory XVI erected the Diocese of Chicago on November 28, 1843. It included all of the new State of Illinois, taking territory from the Dioceses of St. Louis and Vincennes.[13] In 1844, Gregory XVI named Reverend William Quarter of Ireland as the first bishop of Chicago.[9] On his arrival in Chicago, Quarter summoned a synod of the 32 priests to begin the organization of the diocese.[9]

Quarter secured the passage of a state law in 1845 that declared the bishop of Chicago an incorporated entity, giving him the power to hold real estate and other property in trust for religious purposes.[14] This law would allow Quarter and future prelates to construct churches, colleges, and universities in the archdiocese.

Quarter invited the Sisters of Mercy to come to Chicago in 1846. Over the next six years, the sisters founded schools, two orphanages and an academy. One of their projects was the St. Xavier Female Seminary, a secondary school that attracted students from wealthy Catholic and Protestant families.[15]St. Mary of the Lake University, the first university or college in Chicago, opened in 1846.[16]Quarter died on April 10, 1848.[17]

On October 3, 1848, Pope Pius IX appointed Reverend James Van de Velde of the Society of Jesus as the second bishop of Chicago.[18] During his brief tenure in Chicago, Van de Velde built two elementary schools, a night school for adults, an employment office, and a boarding house for working women.[15] After the 1849 cholera outbreak in Chicago, he established residences for the many children orphaned by the epidemic.[15]

1850 to 1860

editVan De Velde opened the Illinois Hospital of the Lakes in 1851, the first hospital in Chicago.[15] Suffering from severe rheumatism during the harsh Chicago winters, Van De Velde persuaded the pope in 1852 to appoint him as bishop of the Diocese of Natchez in Mississippi.[19][20][21] The Vatican erected the Diocese of Quincy in 1853, taking Southern Illinois from the Diocese of Chicago. The Diocese of Quincy later became the Diocese of Alton and then the Diocese of Springfield in Illinois.[13]

On December 1853, Reverend Anthony O'Regan was appointed as the third bishop of Chicago by Pius IX. During his tenure, O'Regan purchased property for the construction of several churches and Calvary Cemetery in Chicago. A systematic administrator and strong disciplinarian, O'Regan generated significant dissatisfaction among his clergy.[22] Many French-speaking congregants accused him of stealing their property.[23][24] In 1855, the Sisters of the Holy Cross founded an industrial school in Chicago for girls, both Catholic and non-Catholic.[15]

Frustrated by the opposition he faced in the diocese, O'Regan submitted his resignation in 1857 to the Vatican, which accepted it in June 1858.[25] The pope appointed Bishop James Duggan of St. Louis as the apostolic administrator of the diocese.

On January 21, 1859, Pius IX named Duggan as the fourth bishop of Chicago.[26] Duggan faced challenges in Chicago: the legacy of the decade-long lack of leadership in the diocese, the aftereffects of the financial panic of 1857, and of the American Civil War. German Catholics were hostile to an Irish bishop. Irish-born priests were hostile to Dugan's stand against the Fenian Brotherhood: he denied the sacraments to anyone tied to this secret society. Some clergy faulted Duggan for failing to support the University of St. Mary of the Lake, which closed in 1866 due to financial problems and low enrollment.[27] In 1859, Dugan founded the House of the Good Shepherd in Chicago as a residence for "delinquent women".[15]

1860 to 1880

editAfter Duggan returned from the Second Plenary Council of Baltimore in 1866, he began to exhibit sign of mental instability. When he left Chicago for a European trip, several diocesan priests wrote to the Vatican, questioning Dugan's mental health.[28] Three years later, in 1869, Pius IX sent Duggan to a sanitarium in St. Louis and appointed Monsignor Thomas Foley as coadjutor bishop to operate the diocese. In 1870, a Jesuit educator, Reverend Arnold Damen, established St. Ignatius College in Chicago.[29]

In October 1871, the diocese suffered nearly a million dollars in property damage in the Great Chicago Fire, including the destruction of St. Mary's Cathedral.[30] [31] In 1875, Foley dedicated the new Cathedral of the Holy Name in Chicago, designed by architect Patrick Keely.[32] Foley invited the Franciscans, Vincentians, Servites, Viatorians, and Resurrectionist religious orders to establish parishes and schools in the diocese. In 1876, disagreements between Foley and Mother Mary Alfred Moes of the Sisters of St. Francis of Mary Immaculate of Joliet led her to relocate her order to Minnesota.[33]

In 1877, the Vatican erected the Diocese of Peoria, taking several counties in Central Illinois from the Diocese of Chicago. Foley died in 1879,

1880 to 1900

editIn 1880, the Vatican elevated the Diocese of Chicago to the Archdiocese of Chicago. At that time, it transferred five more counties to the Diocese of Peoria.[14] Pope Leo XIII named Bishop Patrick Feehan from the Diocese of Nashville as the first archbishop.[34]

From 1880 to 1902, the Catholic population of Chicago nearly quadrupled to 800,000, mainly due to immigration. While the existing Irish and German communities expanded, Polish, Bohemian, French-Canadian, Lithuanian, Italian, Croatian, Slovak and Dutch Catholics arrived in the archdiocese, bringing their own languages and cultural traditions.[35]

During his tenure as archbishop, Feehan founded 140 new parishes. Fifty-two of them were national parishes serving particular ethnic communities, staffed by religious orders from their home countries. The parishes provided the new immigrants with familiar fraternal organizations, music, and language, safe from xenophobia and anti-Catholic discrimination.[35]

In 1881, Feehan established the St. Vincent Orphan Asylum and in 1883 the St. Mary's Training School for Boys. They were followed in 1887 with the founding of St. Paul's Home for Working Boys.[36] A strong supporter of Catholic education, Feehan promoted it with an exhibition at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago[37] "Archbishop Feehan believed a strong system of Catholic education would solve the problem of inconsistent religious instruction at home, and unify a rapidly diversifying Catholic America."[38] He also brought the Vincentians to Chicago to start what is now DePaul University.

1900 to 1930

editAfter Feehan died in 1902, Leo XIII in 1903 named Bishop James Quigley from the Diocese of Buffalo as the next archbishop of Chicago.[39] In 1905, Quigley asked Reverend John De Schryver, a professor at St. Ignatius College Prep in Chicago, to organize St. John Berchmans Parish for Belgian Catholics.[40] Quigley also established parishes for Italian and Lithuanian immigrants. "Chicago's urban parishes flourished as an important spiritual, cultural, and educational component of Chicago's life."[41]

Pope Pius X erected the Diocese of Rockford in 1907, with 12 counties transferred from the Archdiocese of Chicago.[42] In 1910, Quigley approached Reverend Francis X. McCabe, president of DePaul University, about the lack of higher education opportunities for Catholic women in the archdiocese. DePaul began admitting women the following year.[43] Quigley died in 1915.[44]

The next archbishop of Chicago was Auxiliary Bishop George Mundelein from the Diocese of Brooklyn, appointed by Pope Benedict XV on December 9, 1915.[45] Almost half the Chicago population was Catholic by the 1920s. For decades, the parishes had been building and running their own schools, employing religious sisters as inexpensive teachers. The languages of instruction were often German or Polish. On taking office, Mundelein centralized control of the parish schools. The archdiocesan building committee now picked the locations for new schools while its school board standardized the school curricula, textbooks, teacher training, testing, and educational policies.[46]

In 1926, the archdiocese hosted the 28th International Eucharistic Congress.

1930 to 1960

editMundelein died in 1939.[47] To replace him, Pope Pius XII named Archbishop Samuel Stritch from the Archdiocese of Milwaukee.[48] After Stritch died in May 1958, Pius Xll appointed Archbishop Albert Meyer of Milwaukee as archbishop of Chicago on September 19, 1958.[49]

Pius XII erected the Diocese of Joliet in 1948, taking four counties from the Archdiocese of Chicago along with counties from the Dioceses of Rockford and Peoria.[50] This created the current territory of the archdiocese.

On December 1, 1958, a fire at Our Lady of the Angels School in Chicago destroyed part of the school and killed 92 students and three nuns. While visiting survivors in the hospital and viewing the deceased in the city morgue, Meyer was overcome with grief. In 1959, the National Fire Protection Association report on the fire criticized the archdiocese for "housing their children in fire traps". The report noted that the archdiocese continued to operate schools with inadequate fire safety standards. The archdiocese faced $44 million in lawsuits from the families of fire victims and survivors. After six years of negotiations, Meyer agreed to a financial settlement with the victims and survivors.[51]

1960 to 1980

editIn 1960, Meyer banned parishes from hosting bingo games in response to reports of corruption.[16] In January 1961, during riots in the African-American Bronzeville neighborhood of Chicago, Meyer made this statement:

We must remove from the church on the local scene any possible taint of racial discrimination or racial segregation, and help provide the moral leadership for eliminating racial discrimination from the whole community.[16]

After Meyer died in 1965. Pope Paul VI appointed Archbishop John Cody from the Archdiocese of New Orleans as the next archbishop of Chicago. During his tenure in Chicago, many priests and lay people criticized Cody for an autocratic management style. The Association of Chicago Priests censured Meyer in 1971 for failing to advance the Second Vatican Council reforms in the archdiocese. Cody closed 27 schools as well as several parishes in inner city Chicago.[52]

1980 to 1990

editIn September 1981, the US Attorney's Office in Chicago announced an investigation of Cody over the diversion of over $1 million archdiocesan funds to Helen Dolan Wilson, whom Cody described as his step-cousin. That same week, the Chicago Sun-Times revealed that Wilson was on the archdiocesan payroll, but had no discernable duties. Cody denied all charges of wrongdoing.[53]When Cody died in 1982, the official investigation was terminated.

Pope John Paul II in 1982 chose Archbishop Joseph Bernardin of the Archdiocese of Cincinnati as Cody's replacement. Bernardin found an archdiocese in disarray, its priests disheartened by arbitrary administration and charges of financial misconduct under Cody. "With his patient charm and willingness to listen, Bernardin won back the confidence of the clergy and the laity."[54] Within a few months of his arrival in Chicago, Bernadin had spoken personally to every priest in the archdiocese. He also prepared and released an audit of the archdiocesan finances.[55]

During the 1983 mayoral election campaign in Chicago, the African-American Congressman Harold Washington faced bitter opposition from the Chicago political machine. Bernadin urged Chicago Catholics to reject racist attacks against Washington; when he was elected, Bernadin met with Washington the day after the election.[55]

In 1984, Bernadin began the Council of Religious Leaders of Metropolitan Chicago,[56][57] the successor group to the Chicago Conference on Religion and Race.[58] The archdiocese also established covenants with the Episcopal Diocese of Chicago in 1986 and with the Metropolitan Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America in 1989.[56]

1990 to 2020

editIn 1990, Bernadin announced that the archdiocese was closing 37 churches and schools.[59]After Bernadin died in 1996, John Paul II appointed Archbishop Francis George from the Archdiocese of Portland in Oregon as the eighth archbishop of Chicago,[60] George was the first native Chicagoan to become its archbishop.

In 2011, George terminated the foster care program of Catholic Charities in the archdiocese. The State of Illinois had ruled that it would not fund any charities that refused to consider same-sex couples as foster care providers or adoptive parents. George refused to comply with this requirement.[61]

In 2911, the City of Chicago proposed a new route for the June 2012 Chicago Pride Parade, a celebration by the LGBTQ community. However, the archdiocese objected to the new route, saying the parade would pass by Our Lady of Mount Carmel Church during Sunday morning mass. George told an interviewer: "you don't want the Gay Liberation Movement to morph into something like the Ku Klux Klan, demonstrating in the streets against Catholicism."[62] In response, LGBTQ advocates called for George's resignation, but George said:

"When the pastor's request for reconsideration of the plans was ignored, the organizers invited an obvious comparison to other groups who have historically attempted to stifle the religious freedom of the Catholic Church."[63][64]

City administrators negotiated a compromise plan that delayed the parade start by two hours, allowing it to pass by Our Lady after its mass concluded. Two weeks later, George apologized for his remarks.[65] George died in 2014.

Pope Francis named Bishop Blaise Cupich from the Diocese of Spokane as the next archbishop of Chicago. Cupich announced a major reorganization of the archdiocese in 2015. Approximately 50 archdiocesan employees accepted early retirement packages offered by the archdiocese.[66] In 2016, increasing costs, low attendance at mass and priest shortages prompted the archdiocese to close or consolidate up to 100 parishes and schools over the next 15 years.[67]

2020 to present

editOn December 27, 2021, following the issuing of the motu proprio Traditionis custodes in July and the subsequent issuing of guidelines released by the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments in December, Cupich imposed restrictions on the celebration of the traditional Latin mass in the archdiocese. He banned the usage of the Traditional Rite on the first Sunday of every month, Christmas, the Triduum, Easter Sunday, and Pentecost Sunday.[68] In 2021, the archdiocese announced plans to combine 13 parishes into five clusters, to minister to regions south of Chicago.[66]

On August 1, 2022, the Institute of Christ the King Sovereign Priest (ICKSP) announced the celebration of public masses and sacraments at Shrine of Christ the King Church, its headquarters in Chicago.[69] The archdiocese had sent the ICKSP in 2021 its new regulations on the use of the traditional Latin Mass.[70]

As of 2024, 39 churches in Chicago and 21 in the surrounding suburbs have closed and the number of parishes has reduced from 344 to 216.[71] [72]

Sexual abuse

editChurches

editIn the 1950s, Chicago-area Catholics spoke of which churches they attended and identified themselves via these churches. University of Notre Dame professor Kathleen Sprows Cummings stated that knowing one's church revealed demographic information and that it "was an identifier, almost more identifiable than the particular neighborhood that they lived in."[73]

Archbishop's residence

editThe archbishop's residence in Chicago is a private guesthouse owned by the Archdiocese of Chicago. It served as the official residence of the archbishops until 2014, when incoming Archbishop Blaise Cupich decided to live in the rectory of Holy Name Cathedral.[74]

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the archbishop's residence was built in 1885 by Bishop Feehan. A three-story, red brick building, it is one of the oldest structures in the Astor Street District, according to the Landmarks Preservation Council. Before its construction, the bishops of Chicago resided at a home on LaSalle Street and North Avenue. When John Paul II visited Chicago in 1979, he became the first pontiff to stay at the residence. However, both Pius XII and Paul VI resided there during their visits to Chicago as cardinals.[75]

Bishops

editSince 1915, the Vatican has designated each archbishop of Chicago as a cardinal priest, with membership in the College of Cardinals. As such, they also have responsibilities in the dicasteries of the Roman Curia.

- All but two of the bishops and archbishops of Chicago previously served as diocesan priests.

- Bishop Van de Velde belonged to the Society of Jesus and Archbishop George was a member of the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate.[9]

Bishops of Chicago

edit- William J. Quarter (1844–1848)

- James Oliver Van de Velde (1848–1853), appointed Bishop of Natchez

- Anthony O'Regan (1854–1858)

- James Duggan (1859–1880)

Archbishops of Chicago

edit- Patrick Augustine Feehan (1880–1902)

- James Edward Quigley (1903–1915)

- Cardinal George Mundelein (1915–1939)

- Cardinal Samuel Stritch (1939–1958), appointed Pro-Prefect of the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith

- Cardinal Albert Gregory Meyer (1958–1965)

- Cardinal John Cody (1965–1982)

- Cardinal Joseph Bernardin (1982–1996)

- Cardinal Francis George (1997–2014)

- Cardinal Blase J. Cupich (2014–present)

Current auxiliary bishops

edit- Mark Andrew Bartosic (2018–present)

- Robert Gerald Casey (2018–present)

- Jeffrey S. Grob (2020–present)

- Robert J. Lombardo (2020–present)

Former auxiliary bishops

edit- Alexander Joseph McGavick (1899–1921), appointed Bishop of La Crosse

- Peter Muldoon (1901–1908), appointed Bishop of Rockford

- Paul Peter Rhode (1908–1915), appointed Bishop of Green Bay

- Edward Francis Hoban (1922–1928), appointed Bishop of Rockford and later Bishop of Cleveland

- Bernard James Sheil (1928–1969), appointed Archbishop ad personam in 1959

- William David O'Brien (1934–1962)

- William Edward Cousins (1948–1952), appointed Bishop of Peoria and later Archbishop of Milwaukee

- Raymond Peter Hillinger (1956–1971), appointed Bishop of Rockford

- Cletus F. O'Donnell (1960–1967), appointed Bishop of Madison

- Aloysius John Wycislo (1960–1968), appointed Bishop of Green Bay

- Romeo Roy Blanchette (1965–1966), appointed Bishop of Joliet

- John L. May (1967–1969), appointed Bishop of Mobile and later Archbishop of St. Louis

- Thomas Joseph Grady (1967–1974), appointed Bishop of Orlando

- William Edward McManus (1967–1976), appointed Bishop of Fort Wayne-South Bend

- Michael Dempsey (1968–1974)

- Alfred Leo Abramowicz (1968–1995)

- Nevin William Hayes (1971–1988)

- John George Vlazny (1983-1987). appointed Bishop of Winona and later Archbishop of Portland in Oregon

- Plácido Rodriguez (1983–1994), appointed Bishop of Lubbock

- Wilton D. Gregory (1983–1994), appointed Bishop of Belleville and later Archbishop of Atlanta and Archbishop of Washington

- Timothy Joseph Lyne (1983–2013)

- John R. Gorman (1988–2003)

- Thad J. Jakubowski (1988–2003)

- Raymond E. Goedert (1991–2003)

- Gerald Frederick Kicanas (1995–2002), appointed Bishop of Tucson

- Edwin Michael Conway (1995–2004)

- George V. Murry (1995–1998), appointed Coadjutor Bishop of St. Thomas and subsequently succeeded to that see

- John R. Manz (1996–2021)

- Jerome Edward Listecki (2000–2004), appointed Bishop of La Crosse and later Archbishop of Milwaukee

- Thomas J. Paprocki (2003–2010), appointed Bishop of Springfield in Illinois

- Francis J. Kane (2003–2018)

- George J. Rassas (2006–2018)

- Alberto Rojas (2011–2019), appointed Coadjutor Bishop of San Bernardino and later succeeded as bishop

- Ronald Aldon Hicks (2018–2020), appointed Bishop of Joliet

- Joseph N. Perry (1998–2023)

- Andrew Peter Wypych (2011–2023)

- Kevin M. Birmingham (2020–2023)

Other archdiocesan priests who became bishops

edit- Peter Joseph Baltes, appointed Bishop of Alton in 1869

- John McMullen, appointed Bishop of Davenport in 1881

- Maurice Francis Burke, appointed Bishop of Cheyenne in 1887

- Edward Joseph Dunne, appointed Bishop of Dallas in 1893

- Thaddeus Joseph Butler, appointed Bishop of Concordia in 1897 (died before his consecration)

- Edmund Michael Dunne, appointed Bishop of Peoria in 1909

- Stanislaus Vincent Bona, appointed Bishop of Grand Island in 1931

- Moses Elias Kiley, appointed Bishop of Trenton in 1934

- Francis Joseph Magner, appointed Bishop of Marquette in 1940

- Patrick Thomas Brennan,(priest here, 1928–1936), appointed Prefect of Kwoszu, Korea (South) in 1948

- Martin Dewey McNamara, appointed Bishop of Joliet in Illinois in 1948

- William Aloysius O'Connor, appointed Bishop of Springfield in Illinois in 1948

- Donald Martin Carroll, appointed Bishop of Rockford in 1956 (did not take effect)

- Ernest John Primeau, appointed Bishop of Manchester in 1959

- Romeo Roy Blanchette, appointed Auxiliary Bishop of Joliet in Illinois in 1965

- Raymond James Vonesh, appointed Auxiliary Bishop of Joliet in Illinois in 1968

- Paul Casimir Marcinkus, appointed titular Archbishop in 1968

- Thomas Joseph Murphy, appointed Bishop of Great Falls in 1978

- John Richard Keating, appointed Bishop of Arlington in 1983

- James Patrick Keleher, appointed Bishop of Belleville in 1984

- Edward Michael Egan, appointed Auxiliary Bishop of New York in 1985; future Cardinal

- Edward James Slattery, appointed Bishop of Tulsa in 1993

- Edward Kenneth Braxton, appointed Auxiliary Bishop of St. Louis in 1995

- Robert Emmet Barron, appointed Auxiliary Bishop of Los Angeles in 2015; appointed bishop of Winona-Rochester in 2022

- Michael G. McGovern, appointed Bishop of Belleville in 2020

- Louis Tylka, appointed Coadjutor Bishop of Peoria in 2020 and subsequently succeeded to that see

Structure of the archdiocese

editPastoral centers

editThe archdiocese operates the Archbishop Quigley and Cardinal Meyer pastoral centers in Chicago.

Departments

editAs of 2024, the archdiocese has the following departments, agencies and offices:

- Amate House

- Archdiocesan Council of Catholic Women

- Archives and Records

- Assistance Ministry

- Catechesis and Youth Ministry

- Catholic Cemeteries

- Catholic Charities

- Chicago Airports Catholic Chaplaincy

- Catholic Schools

- Chancellor's Office

- Communications and Public Relations

- Conciliation

- Diaconate

- Divine Worship

- Ecumenical and Interreligious Affairs

- Family Ministries

- Financial Services

- Lay Ecclesial Ministry

- Legal Services

- Liturgy Training Publications

- Metropolitan Tribunal

- Ecumenical and Interreligious Affairs

- Evangelization and Missionary Discipleship

- Information Technology

- Human Dignity and Solidarity

- Persons with Disabilities

- Parish Vitality and Mission

- Protection of Children and Youth

- Planning and Construction

- Respect Life

- Stewardship and Development

- Vocations

- Young Adult Ministry

- Youth Ministry[76]

Office of Catholic Schools

editThe Office of Catholic Schools operates a system of primary and secondary schools in the archdiocese. A 2015 article in the Chicago Tribune described the archdiocesan schools as the largest private school system in the United States.[77]

The first school in the archdiocese was a boy's school, opened in Chicago in 1844. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, the archdiocese established schools serving Germans, Poles, Czechs, Bohemians, French, Slovaks, Lithuanians, Puerto Rican Americans, African Americans, Italians, and Mexicans. Many of these schools were founded by religious sisters.[78]The school construction boom in the archdiocese ended when Cardinal Cody freezed school construction in Lake County and suburban Cook County.

Between 1984 and 2004, the archdiocese closed 148 schools and 10 school sites.[79] By 2005, over half of its urban schools had closed.[80] In January 2018, the archdiocese announced the closure of five school and In January 2020 it closed five more schools.[78] [27]As of 2022, the archdiocese contained 33 secondary schools; seven were all-girls. seven were all-boys and 19 were co-ed[81] The system had an enrollment of 44,460 students in its primary schools and 19,200 in its secondary schools.[82]

Respect Life Office

editCardinal George established the Respect Life Office in the archdiocese. It provides educational resources and a speakers bureau, and sponsors conferences, retreats and rallies. The Office runs Project Rachel Post Abortion Healing, a program for women who have abortion procedures; and the Chastity Education Initiative, which advises youth and young adults on sexuality issues.[83][84]

The office has coordinated the local 40 Days for Life campaign and trips to the March for Life rallies in both Chicago and Washington, DC, for college and high school students.[85][86]

Seminary

edit- University of Saint Mary of the Lake (Mundelein Seminary) – major seminary

Province of Chicago

editSee also

edit- Category:Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago

- The Catholic New World, the official newspaper of the Archdiocese

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help (Glenview, Illinois), one of the largest parishes in the Archdiocese

- Polish Cathedral style churches of Chicago

- St. Anne Catholic Community, another of the largest parishes in the Archdiocese

- Ukrainian Catholic Eparchy of Chicago

- Syro-Malabar Catholic Diocese of Saint Thomas the Apostle of Chicago

- List of the Roman Catholic bishops of the United States

- List of the Roman Catholic cathedrals of the United States

- List of the Roman Catholic dioceses of the United States

- United States Conference of Catholic Bishops

- Sexual abuse scandal in the Catholic archdiocese of Chicago

- Shrine of Christ the King, Sovereign Priest; in Chicago, Illinois[87]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e "Facts and Figures - Archdiocese of Chicago". www.archchicago.org.

- ^ Joshua J. McElwee (September 21, 2014). "Exclusive: Chicago's new archbishop talks about 'stepping into the unknown'". National Catholic Reporter. Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- ^ "Cardinal Blase J. Cupich Names Bishop Robert G. Casey New Vicar General of Archdiocese of Chicago" (Press release). Archdiocese of Chicago. August 28, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ "A Consistent Ethic of Life: Continuing the Dialogue". www.priestsforlife.org. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

- ^ Monet, J. (1979). "Marquette, Jacques". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. University of Toronto/Laval University. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ "Jacques Gravier", Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online, accessed 1 Mar 2010

- ^ Department Of State. The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affairs. "Treaty of Paris, 1783". 2001-2009.state.gov. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ "Summer 1795: The Treaty of Greenville creates an uneasy peace (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Melody, John (1908). "Archdiocese of Chicago". Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ "Saint Louis (Archdiocese) [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ "History - Old St. Mary's Chicago". oldstmarys.com. July 24, 2017. Retrieved November 15, 2024.

- ^ "Father O'Meara biography". St. Dennis Church. Archived from the original on March 10, 2007. Retrieved April 29, 2006.

- ^ a b "Chicago (Archdiocese) [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved November 15, 2024.

- ^ a b Avella, Steven M. (2005). "Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago". Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago Historical Society/Newberry Library. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Walch, Timothy (1978). "Catholic Social Institutions and Urban Development: The View from Nineteenth-Century Chicago and Milwaukee". The Catholic Historical Review. 64 (1): 16–32. ISSN 0008-8080.

- ^ a b c "Albert Cardinal Meyer Is Dead;I Archbishop of Chicago Was 621; Leader of Largest A rchdioces in U.S. Urged Interfaith Ties at Council in Rome". The New York Times. April 10, 1965. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ "Bishop William Quarter (1806–1848)". Offaly Historical & Archaeological Society. September 2, 2007. Archived from the original on January 5, 2006. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ "Bishop James Oliver Van de Velde [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved November 17, 2024.

- ^ De Smet, Pierre-Jean. Death of Bishop Van de Velde Archived 2012-10-20 at the Wayback Machine, 1855 eulogy to Belgian newsletter by fellow Belgian-born Jesuit; accessed April 12, 2009.

- ^ Biographical Sketch of Bishop James O. Van de Velde, S. J. Archived 2011-07-28 at the Wayback Machine, St. Mary Basilica Archives. Accessed April 13, 2009.

- ^ Archdiocese of Chicago: (Chicagiensis), New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia. Accessed April 15, 2009.

- ^ Garraghan, Gilbert Joseph. The Catholic Church in Chicago, 1673–1871.

- ^ Clarke, Richard Henry. Lives of the deceased bishops of the Catholic Church in the United States.

- ^ "Founding Fathers". Hidden Truths: Catholic Cemetery.

- ^ "Meet the previous leaders of the church in Chicago". Chicago Catholic. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ "Bishop James Duggan [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ a b Hope, Leah; Elgas, Rob; Hickey, Megan (January 19, 2018). "Archdiocese of Chicago to close 5 Catholic schools". ABC7 Chicago.

- ^ John J. Treanor, "Chicago's fourth bishop "home" after 102 years" The Catholic New World April 1, 2001 "The Catholic New World - 04/01/01 - Final chapter, final rest: Chicago's fourth bishop "home" after 102 years". Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved September 26, 2010.

- ^ Young, Kathy. "Research Guides: Archives and Special Collections: History of Loyola University Chicago". libguides.luc.edu. Retrieved February 3, 2016.

- ^ Avella, Steven M., "Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago",Encyclopedia of Chicago, 2005, Chicago Historical Society

- ^ "History - Old St. Mary's Chicago". oldstmarys.com. July 24, 2017. Retrieved November 22, 2024.

- ^ Holy Name Cathedral, history

- ^ "History of Mayo Clinic Hospital, Saint Marys Campus", Mayo Clinic

- ^ "Archbishop Patrick Augustine Feehan [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ a b Brachear, Manya A., "Chicago's first archbishop was 'good prelate, good man'" Chicago Tribune, May 19, 2013

- ^ Tribune, Chicago (May 19, 2013). "Chicago's first archbishop was 'good prelate, good man'". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved November 19, 2024.

- ^ "From Feehan to Cupich: meet Chicago's Catholic leaders" Chicago Tribune, September 23, 2014

- ^ Mercado, Monica. "Archbishop Patrick A. Feehan and Catholic Chicago", Faith in the City

- ^ "Meet the previous leaders of the church in Chicago". Chicago Catholic. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ ""Our History", St. John Berchmans School". Archived from the original on June 28, 2022. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- ^ Avella, Steven. "Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago", Encyclopedia of Chicago

- ^ "Rockford (Diocese) [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved November 22, 2024.

- ^ "Into the Archives | Sections | DePaul University Newsline | DePaul University, Chicago". resources.depaul.edu. Retrieved November 19, 2024.

- ^ "Archbishop James Edward Quigley [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ "George William Cardinal Mundelein [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ James W. Sanders, The education of an urban minority: Catholics in Chicago, 1833-1965 (Oxford UP, 1977) pp. 126-136, 147-160.

- ^ "George William Cardinal Mundelein [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ "Samuel Alphonsus Cardinal Stritch [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ "Albert Gregory Cardinal Meyer [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ "Chicago (Archdiocese) [Catholic-Hierarchy]". www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved November 22, 2024.

- ^ "Albert Cardinal Meyer Is Dead;I Archbishop of Chicago Was 621; Leader of Largest A rchdioces in U.S. Urged Interfaith Ties at Council in Rome". The New York Times. April 10, 1965. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ "JOHN CARDINAL CODY DIES; CHICAGO LEADER WAS 74". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 22, 2024.

- ^ "CARDINAL CODY INVESTIGATION IS NOW THE TALK OF CHICAGO". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 22, 2024.

- ^ Death as a Friend "Death as a Friend", The New York Times Magazine, December 1, 1996]

- ^ a b "CHICAGO'S ACTIVIST CARDINAL". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 22, 2024.

- ^ a b Bernardin, Joseph (2000). Spilly, Alphonse P. (ed.). Selected Works of Joseph Cardinal Bernardin: Church and society. Liturgical Press. p. 339. ISBN 978-0-8146-2584-2.

- ^ Frisbie, Margery (2002). An Alley in Chicago: The Life and Legacy of Monsignor John Egan. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 266. ISBN 978-1-58051-121-6.

- ^ Baima, Thomas A. (2012). "What We Have Learned from 40 Years of Catholic–Jewish Dialogue". A Legacy of Catholic-Jewish Dialogue: The Cardinal Joseph Bernardin Jerusalem Lectures. ISBN 978-1-61671-063-7.

- ^ Marx, Gary (January 29, 1990). "CHURCHES MAY SHUT, COMMUNITY DOESN'T". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ "Francis George Biography". Archdiocese of Chicago. Archived from the original on August 15, 2009. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

- ^ Goodstein, Laurie (April 18, 2015). "Cardinal Francis E. George, 78, Dies; Urged 'Zero Tolerance' in Abuse Scandal". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- ^ "Cardinal Francis George Warns That Chicago Gay Pride Parade Might 'Morph Into Ku Klux Klan'". Fox News Chicago. December 21, 2011. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ "Cardinal Defends KKK Analogy, Stokes Controversy". NBC Chicago. December 28, 2011. Retrieved November 21, 2014.

- ^ Erbentraut, Joseph (December 29, 2011). "Cardinal George Stands By KKK Comment, Calls For His Resignation Continue". Huffington Post. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ "Cardinal Apologizes For Linking Gay Parade To KKK". Huffington Post. January 7, 2012. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ a b "Chicago archdiocese announces another round of parish mergers". The Catholic Telegraph. CNA. March 12, 2021.

- ^ "Archdiocese May Close Nearly 100 Churches in Next 15 Years". Curbed Chicago. February 9, 2016.

- ^ Reis, Bernadette Mary (December 27, 2021). "Cardinal Blase Cupich publishes policy implementing Traditionis custodes". Vatican News. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ^ "Events". Institute of Christ the King Sovereign Prince. August 3, 2022.

- ^ "Public Masses suspended at Chicago's Christ the King shrine". Catholic News Agency. Retrieved November 24, 2024.

- ^ "Decrees and Letters - Church Relegations". Archdiocese of Chicago. Retrieved July 3, 2024.

- ^ Ahern, Mary Ann (February 8, 2022). "Major Overhaul Will Leave Chicago Archdiocese With 123 Fewer Parishes By July". NBC 5 Chicago.

- ^ "Angels Too Soon: The Tragedy of the 1958 Our Lady of the Angels School Fire". WTTW. Retrieved April 3, 2024.

- ^ "Archbishop Residence Chicago | Chicago Gold Coast Walking Tour | eVisitorGuide". www.evisitorguide.com. Retrieved November 15, 2024.

- ^ "The Archbishop's Residence -- Chicago Tribune". galleries.apps.chicagotribune.com. May 9, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ "Departments and Agencies" (shtm). Archdiocese of Chicago. Retrieved April 29, 2006.

- ^ Crosby, Rachel (August 27, 2015). "Chicago Catholic Schools names new superintendent". Chicago Tribune. Chicago. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ a b "Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago to Close 5 Schools". NBC Chicago. January 13, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ Simons, Paul. "Closed School History: 1984–2004" (PDF). Archdiocese of Chicago. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ Skerrett, Ellen (2005). "Catholic School System". Chicago Historical Society/Newberry Library. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ "Six decades later, officials say Regina Dominican's all-girls education increasingly relevant". Chicago Tribune. March 26, 2019. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- ^ "Facts and Figures - Archdiocese of Chicago". www.archchicago.org. Retrieved November 23, 2024.

- ^ "Respect Life Office". Archdiocese of Chicago. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ "Chastity Education Initiative | Respect Life and Chastity Education - Parish Vitality and Mission". pvm.archchicago.org. Retrieved November 17, 2024.

- ^ ""March for Life Chicago" to Mark Respect Life Month Activities" (Press release). Archdiocese of Chicago. January 16, 2014.

- ^ DeFiglio, Pam (October 12, 2008). "Crowd kicks off '40 Days for Life' prayer vigil". Catholic New World. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ "Information, Schedule & Directions". Shrine of Christ the King. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

Further reading

edit- Coughlin, Roger J. Charitable Care in the Archdiocese of Chicago (Chicago: The Catholic Charities, 2009)

- Dahm, Charles W. Power and Authority in the Catholic Church: Cardinal Cody in Chicago (University of Notre Dame Press, 1981)

- Faraone, Dominic E. "Urban Rifts and Religious Reciprocity: Chicago and the Catholic Church, 1965–1996." (2013, PhD, Marquette University); Bibliography pages 359–86. online

- Garrathan, Gilbert J. The Catholic Church in Chicago, 1673–1871 (Loyola University Press, 1921)

- Greeley, Andrew M. Chicago Catholics and the struggles within their Church (Transaction Publishers, 2011)

- Hoy, Suellen. Good Hearts: Catholic Sisters in Chicago's Past (University of Illinois Press, 2006)

- Kantowicz, Edward R. Corporation Sole: Cardinal Mundelein and Chicago Catholicism (University of Notre Dame Press, 1983)

- Kantowicz, Edward R. The Archdiocese of Chicago: A Journey of Faith (Ireland: Booklink, 2006)

- Kelliher, Thomas G. Hispanic Catholics and the Archidiocese of Chicago, 1923–1970 (PhD Diss. UMI, Dissertation Services, 1998)

- Kennedy, Eugene. This Man Bernardin (Loyola U. Press, 1996)

- Koenig, Rev. Msgr. Harry C., S.T.D., ed. Caritas Christi Urget Nos: A History of the Offices, Agencies, and Institutions of the Archdiocese of Chicago (2 vols. Catholic Bishop of Chicago, 1981)

- Koenig, Rev. Msgr. Harry C., S.T.D., ed. A History of the Parishes of the Archdiocese of Chicago. (2 vols. Catholic Bishop of Chicago, 1980)

- McMahon, Eileen M. What Parish Are You From?: A Chicago Irish Community and Race Relations (University Press of Kentucky, 1995)

- Neary, Timothy B. "Black-Belt Catholic Space: African-American Parishes in Interwar Chicago." US Catholic Historian (2000): 76–91. in JSTOR

- Parot, Joseph John. Polish Catholics in Chicago: 1850–1920: a Religious History (Northern Illinois University Press, 1981.)

- Reiff, Janice L. et al., eds. The Encyclopedia of Chicago (University of Chicago Press, 2004) online

- Sanders, James W. The education of an urban minority: Catholics in Chicago, 1833–1965 (Oxford University Press, 1977)

- Shanabruch, Charles. Chicago's Catholics: The evolution of an American identity (Univ of Notre Dame Press, 1981)

- Skerrett, Ellen. "The Catholic Dimension." in Lawrence J. McCaffrey et al. eds. The Irish in Chicago (University of Illinois Press, 1987)

- Skerrett, Ellen. Chicago's Neighborhoods and the Eclipse of Sacred Space (University of Notre Dame Press, 1994)

- Skerrett, Ellen. et al. eds., Catholicism, Chicago Style (Loyola University Press, 1993)

- Skok, Deborah A. More Than Neighbors: Catholic Settlements and Day Nurseries in Chicago, 1893–1930 (Northern Illinois University Press, 2007)

- Wall, A.E.P. The Spirit of Cardinal Bernardin (Chicago: Thomas More Press, 1983)