This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2023) |

Chlamydia psittaci is a lethal intracellular bacterial species that may cause endemic avian chlamydiosis, epizootic outbreaks in other mammals, and respiratory psittacosis in humans. Potential hosts include feral birds and domesticated poultry, as well as cattle, pigs, sheep, and horses. C. psittaci is transmitted by inhalation, contact, or ingestion among birds and to mammals. Psittacosis in birds and in humans often starts with flu-like symptoms and becomes a life-threatening pneumonia. Many strains remain quiescent in birds until activated by stress. Birds are excellent, highly mobile vectors for the distribution of chlamydia infection, because they feed on, and have access to, the detritus of infected animals of all sorts.

| Chlamydia psittaci | |

|---|---|

| |

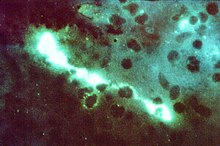

| Direct fluorescent antibody stain of a mouse brain impression smear showing C. psittaci. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Chlamydiota |

| Class: | Chlamydiia |

| Order: | Chlamydiales |

| Family: | Chlamydiaceae |

| Genus: | Chlamydia |

| Species: | C. psittaci

|

| Binomial name | |

| Chlamydia psittaci (Lillie 1930) Everett et al. 1999[1]

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Chlamydophila psittaci | |

Chlamydia psittaci in birds is often systemic, and infections can be inapparent, severe, acute, or chronic with intermittent shedding.[2][3][4] C. psittaci strains in birds infect mucosal epithelial cells and macrophages of the respiratory tract. Septicaemia eventually develops and the bacteria become localized in epithelial cells and macrophages of most organs, conjunctiva, and gastrointestinal tracts. It can also be passed in the eggs. Stress will commonly trigger onset of severe symptoms, resulting in rapid deterioration and death. C. psittaci strains are similar in virulence, grow readily in cell culture, have 16S rRNA genes that differ by <0.8%, and belong to eight known serotypes. All should be considered to be readily transmissible to humans.

Chlamydia psittaci serovar A is endemic among psittacine birds and has caused sporadic zoonotic disease in humans, other mammals, and tortoises. Serovar B is endemic among pigeons, has been isolated from turkeys, and has also been identified as the cause of abortion in herds of dairy cattle. Serovars C and D are occupational hazards for slaughterhouse workers and for people in contact with birds. Serovar E isolates (known as Cal-10, MP or MN) have been obtained from a variety of avian hosts worldwide and, although they were associated with the 1920s–1930s outbreak in humans, a specific reservoir for serovar E has not been identified. The M56 and WC serovars were isolated during outbreaks in mammals. Many C. psittaci strains are susceptible to bacteriophages.

Life cycle and method of infection

editChlamydia psittaci is a small bacterium (0.5μm) that undergoes several transformations during its lifecycle. It exists as an elementary body (EB) between hosts. The EB is not biologically active, but is resistant to environmental stresses and can survive outside a host. The EB travels from an infected bird to the lungs of an uninfected bird or person in small droplets, and is responsible for infection. Once in the lungs, the EB is taken up by cells in a pouch called an endosome by phagocytosis. However, the EB is not destroyed by fusion with lysosomes, as is typical for phagocytosed material. Instead, it transforms into a reticulate body and begins to replicate within the endosome. The reticulate bodies must use some of the host's cellular machinery to complete their replication. The reticulate bodies then convert back to elementary bodies, and are released back into the lung, often after causing the death of the host cell. The EBs are thereafter able to infect new cells, either in the same organism or in a new host. Thus, the lifecycle of C. psittaci is divided between the elementary body which is able to infect new hosts, but can not replicate, and the reticulate body, which replicates, but is not able to cause new infection.

History

editThe disease caused by C. psittaci, psittacosis, was first characterized in 1879 when seven individuals in Switzerland were found to experience pneumonia after exposure to tropical pet birds. The causative pathogen was not known. The related bacterial species Chlamydia trachomatis was described in 1907, but was assumed to be a virus, as it could not be grown on artificial media. In the winter of 1929–1930, a psittacosis pandemic spread across the United States and Europe. Its mortality rate was 20% and as high as 80% for pregnant women. The disease's spread was eventually attributed to exposure to Amazon parrots imported from Argentina. Though C. psittaci was identified in 1930 as the agent responsible for psittacosis, it was not found to be a bacterium until examination by electron microscopy in the 1960s.[5]

Taxonomy

editFor several decades, the family Chlamydiaceae contained a sole genus, Chlamydia. C. psittaci was originally classified from the 1960s to 1999 as a species of this sole genus. In 1999, the order Chlamydiales was assigned two new families (Parachlamydiaceae and Simkaniaceae), and within the family Chlamydiaceae, the genus Chlamydia was divided into two genera, Chlamydia and the newly designated genus Chlamydophila, with C. psittaci becoming Chlamydophila psittaci.[1] However, this reclassification "was not wholly accepted or adopted"[6] among microbiologists, which "resulted in a reversion to the single, original genus Chlamydia, which now encompasses all 9 species including C. psittaci."[6] A new species was added to the reunited genus Chlamydia in 2013,[7] two more were added in 2014.[8]

What were once classified as the mammal-endemic C. psittaci abortion, 'C. psittaci feline, and C. psittaci guinea pig are today three separate species, C. abortus, C. felis, and C. caviae.

Diseases

editChlamydia psittaci infection is also associated with schizophrenia. Many other kinds of infections have been associated with schizophrenia.[9]

Genomics

editLike other Chlamydia, C. psittaci is an intracellular pathogen and has thus undergone significant genome reduction. Most C. psittaci genomes encode between 1,000 and 1,400 proteins. A total of 911 core genes were found to be present in all 20 strains sequenced by Read et al., corresponding to 90% of the genes present in each genome.[10]

Confirmation of diagnosis

editIn addition to symptoms and CHX, complement fixation, microimmunofluorescence, and polymerase chain reaction tests can be used to confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment

editTetracycline or macrolides can be used to treat this condition. The drugs are given intravenously or orally, depending on drug choice. Treatment should continue for 10–14 days after the fever subsides. In children or pregnant women, though, tetracycline should not be used. Ibuprofen or acetominophen, and fluids are also administered. Cannabis or tobacco smoke should be avoided. While taking tetracycline, dairy products should be avoided.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Everett KD, Bush RM, Andersen AA (April 1999). "Emended description of the order Chlamydiales, proposal of Parachlamydiaceae fam. nov. and Simkaniaceae fam. nov., each containing one monotypic genus, revised taxonomy of the family Chlamydiaceae, including a new genus and five new species, and standards for the identification of organisms". International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology. 49 Pt 2 (2): 415–40. doi:10.1099/00207713-49-2-415. PMID 10319462.

- ^ Andersen AA (September 2005). "Serotyping of US isolates of Chlamydophila psittaci from domestic and wild birds". J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 17 (5): 479–82. doi:10.1177/104063870501700514. PMID 16312243.

- ^ Dorrestein GM, Wiegman LJ (December 1989). "[Inventory of the shedding of Chlamydia psittaci by parakeets in the Utrecht area using ELISA]". Tijdschr Diergeneeskd (in Dutch). 114 (24): 1227–36. PMID 2617495.

- ^ Sareyyupoglu B, Cantekin Z, Bas B (2007). "Chlamydophila psittaci DNA detection in the faeces of cage birds". Zoonoses Public Health. 54 (6–7): 237–42. doi:10.1111/j.1863-2378.2007.01060.x. PMID 17803512. S2CID 9087999.

- ^ Harkinezhad, Taher; Geens, Tom; Vanrompay, Daisy (1 March 2009). "Chlamydophila psittaci infections in birds: A review with emphasis on zoonotic consequences". Veterinary Microbiology. 135 (1–2): 68–77. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.09.046. PMID 19054633.

- ^ a b Balsamo G, Maxted AM, Midla JW, Murphy JM, Wohrle R, Edling TM, et al. (September 2017). "Compendium of Measures to Control Chlamydia psittaci Infection Among Humans (Psittacosis) and Pet Birds (Avian Chlamydiosis), 2017" (PDF). Journal of Avian Medicine and Surgery. 31 (3): 262–282. doi:10.1647/217-265. PMID 28891690.

- ^ Vorimore F, Hsia RC, Huot-Creasy H, Bastian S, Deruyter L, Passet A, Sachse K, Bavoil P, Myers G, Laroucau K (20 September 2013). "Isolation of a New Chlamydia species from the Feral Sacred Ibis (Threskiornis aethiopicus): Chlamydia ibidis". PLOS ONE. 8 (9): e74823. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...874823V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0074823. PMC 3779242. PMID 24073223.

- ^ Joseph SJ, Marti H, Didelot X, Castillo-Ramirez S, Read TD, Dean D (October 2015). "Chlamydiaceae Genomics Reveals Interspecies Admixture and the Recent Evolution of Chlamydia abortus Infecting Lower Mammalian Species and Humans". Genome Biology and Evolution. 7 (11): 3070–84. doi:10.1093/gbe/evv201. PMC 4994753. PMID 26507799.

- ^ Arias I (April 2012). "Infectious agents associated with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis". Schizophr. Res. 136 (1–3): 128–36. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2011.10.026. hdl:10481/90076. PMID 22104141. S2CID 2687441.

- ^ Read TD, Joseph SJ, Didelot X, Liang B, Patel L, Dean D (March 2013). "Comparative analysis of Chlamydia psittaci genomes reveals the recent emergence of a pathogenic lineage with a broad host range". mBio. 4 (2): e00604–12. doi:10.1128/mBio.00604-12. PMC 3622922. PMID 23532978.

Further reading

edit- Brock Biology of Microorganisms (10th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. 2003. ISBN 978-0-13-049147-3.