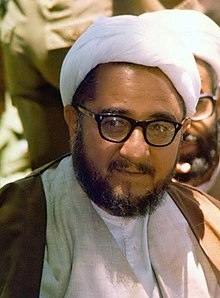

Mohammed Sadeq Givi Khalkhali (Persian: محمدصادق گیوی خلخالی; 27 July 1926 – 26 November 2003)[3] was an Iranian Shia cleric who is said to have "brought to his job as Chief Justice of the revolutionary courts a relish for summary execution" that earned him a reputation as Iran's "hanging judge".[4][5][6] A farmer's son from Iranian Azeri origins was born in Givi, Azerbaijani SSR, in the Soviet Union (now in Azerbaijan).[7] He is also reported to have born in Kivi, in the Khalkhal County, Iran (ergo his name).[8] Khalkhali has been described as "a small, rotund man with a pointed beard, kindly smile, and a high-pitched giggle" by The Daily Telegraph.[4]

Sadegh Khalkhali | |

|---|---|

| |

| Head of Islamic Revolutionary Court | |

| In office 24 February 1979 – 1 March 1980 | |

| Appointed by | Ruhollah Khomeini |

| Succeeded by | Hossein Mousavi Tabrizi |

| Member of the Parliament of Iran | |

| In office 28 May 1980 – 28 May 1992 | |

| Constituency | Qom |

| Majority | 106,647 (54.8%) |

| Member of the Assembly of Experts | |

| In office 15 August 1983 – 21 February 1991 | |

| Constituency | Tehran Province[1] |

| Majority | 1,048,284 (32.87%) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Mohammed-Sadeq Sadeqi Givi 27 July 1926 Givi, Khalkhal, Ardabil Province, Iran |

| Died | 26 November 2003 (aged 77) Tehran, Iran |

| Political party |

|

| Children | 3 |

| Alma mater | Qom Seminary |

| Occupation | Judge; Executioner |

| Nickname | Hanging Judge[2] |

Career and activities

editKhalkhali was one of Khomeini's circle of disciples as far back as 1955[9] and reconstructed the former secret society of Islamic assassins known as the Fadayan-e Islam after its suppression,[10] but was not a well-known figure to the public prior to the Islamic Revolution.

On 24 February 1979, Khalkhali was chosen by Ruhollah Khomeini to be the Sharia ruler (Persian: حاکم شرع) or head the newly established Revolutionary Courts, and to make Islamic rulings. In the early days of the revolution he sentenced to death "hundreds of former government officials" on charges such as "spreading corruption on earth" and "warring against God."[11] Most of the condemned did not have access to a lawyer or a jury. Following the Iranian Revolution in 1979, Reza Shah's mausoleum was destroyed under the direction of Khalkhali, which was sanctioned by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.[12]

Khalkhali ordered the executions of Amir Abbas Hoveida,[13] the Shah's longtime prime minister, and Nematollah Nassiri, a former head of SAVAK. According to one report, after sentencing Hoveida to death:

Pleas for clemency poured in from all over the world and it was said that Khalkhali was told by telephone to stay the execution. Khalkhali replied that he would go and see what was happening. He then went to Hoveyda and either shot him himself or instructed a minion to do the deed. "I'm sorry," he told the person at the other end of the telephone, "the sentence has already been carried out."[4]

Another version of the story has Khalkhali saying that while presiding over Hoveida's execution he made sure communication links between Qasr Prison and the outside world were severed, "to prevent any last-minute intercession on his behalf by Mehdi Bazargan, the provisional prime minister."[14]

By trying Hoveida, Khalkhali effectively undermined the position of the provisional prime minister of the Islamic Revolution, the moderate Mehdi Bazargan, who disapproved of the Islamic Revolutionary Court and sought to establish the Revolution's reputation for justice and moderation.

Khalkhali held antipathy towards pre-Islamic Iran. In 1979 he wrote a book "branding king Cyrus the Great a tyrant, a liar, and a homosexual" and "called for the destruction of the Tomb of Cyrus and remains of the two-thousand-year-old Persian palace in Shiraz, Fars Province, the Persepolis."[15] According to an interview by Elaine Sciolino of Shiraz-based Ayatollah Majdeddin Mahallati, Khalkhali came to Persepolis with "a band of thugs" and gave an angry speech demanding that "the faithful torch the silk-lined tent city and the grandstand that the Shah had built," but was driven off by stone-throwing local residents.[16]

At the height of the Iran hostage crisis in 1980 following the failure of the American rescue mission Operation Eagle Claw and crash of U.S. helicopters killing their crews, Khalkhali appeared on television "ordering the bags containing the dismembered limbs of the dead servicemen to be split open so that the blackened remains could be picked over and photographed," to the anger of American viewers.[4]

Khalkhali, in his positions in the Islamic Revolutionary government, made it his mission to eliminate the community of Bahá'ís in Iran (the largest non-Muslim religious minority). Bahá'ís were stripped of any civil and human rights they had previously been permitted and more than 200 executed or killed in the early years of the Islamic Republic. All Bahá'í properties were seized, including its holiest site, the House of the Báb in Shiraz, which was turned over by the government to Khalkhali for the activities of the Fada'iyan-i-Islam.[17][18] The site was subsequently razed, along with the entire neighborhood, for the construction of a mosque and a new road. In addition to presiding over the Islamic Revolutionary Court that brought about the execution of dozens of members of elected Bahá'í Councils, Khalkhali murdered a Bahá'í, Muhammad Muvahhed, who disappeared in 1980 into the revolutionary prison system. It was later reported that Khalkhali personally went to Muvahhed's cell, demanded that he recant his faith and become a Muslim. When Muvahhed refused, Khalkhali covered his face with a pillow and shot him in the head.[19]

Khalkhali later investigated and ordered the execution of many activists for federalism in Kurdistan and Turkmen Sahra,[4] At the height of its activity, Khalkhali's revolutionary court sentenced to death "up to 60 Kurds a day."[4] Following that, in August 1980 he was asked by President Banisadr to take charge of trying and sentencing drug dealers, and sentenced hundreds to death.[20] One of the complaints of the revolution's leader and Khalkhali's superior, the Ayatollah Khomeini against the regime they had overthrown was that the Shah's far more limited number of executions of drug traffickers had been "inhuman."[21]

In December 1980 his influence waned when he was forced to resign from the revolutionary courts because of his failure to account for $14 million seized through drug raids, confiscations, and fines, although some believe this as much the doing of President Bani-Sadr and the powerful head of the Islamic Republic Party Ayatollah Mohammad Beheshti "working behind the scenes" to remove a source of bad publicity for the revolution, as a matter of outright corruption.[21][22]

In an interview, Khalkhali personally confirmed ordering more than 100 executions[citation needed], although many sources believe that by the time of his death he had sent 8,000 men and women to their deaths. In some cases he was the executioner[citation needed], where he executed his victims using machine guns[citation needed]. In an interview with the French newspaper Le Figaro he is quoted as saying, "If my victims were to come back on earth, I would execute them again, without exceptions."[4]

Khalkhali was elected as representative for Qom in Islamic Consultative Assembly for two terms, serving for "more than a decade." In 1992, however, he was one of 39 incumbents from the Third Majles and 1000 or so candidates rejected that winter and spring by the Council of Guardians, which vets candidates. The reason given was a failure to show a "practical commitment to Islam and to the Islamic government," but it was thought by some to be a purge of radical critics of the conservatives in power.[23]

Khalkhali sided with reformists after the election of President Mohammad Khatami in 1997, although he was never really accepted by the movement.[24]

Later years and death

editKhalkhali retired to Qom, where he taught Islamic seminarians.

He died in 2003, at the age of 77, of cancer and heart disease.[25][26][27] At the time of his death, the speaker of Parliament, Mehdi Karoubi, praised the judge's performance in the early days of the revolution.[24][28]

Personal life

editKhalkhali was married and had a son and two daughters. His daughter, Fatemeh Sadeqi, though born in a restrictive Islamic environment, has attended university, attained PhD and is now known for her secular views.[29] She was the author of "Why We Say No to Forced Hijab" — a widely circulated 2008 essay.[30]

Electoral history

edit| Year | Election | Votes | % | Rank | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | Constitutional Experts | 122,217 | 4.8 | 18th | Lost[31] |

| 1980 | Parliament | 123,136 | 78.9 | 1st | Won[32] |

| 1982 | Assembly of Experts | 1,048,284 | 32.87 | 15th | Went to run-off |

| Assembly of Experts run off | No Data Available | 1st | Won | ||

| 1984 | Parliament | 144,160 | 67.1 | 1st | Won[33] |

| 1988 | Parliament | 106,647 | 54.8 | 1st | Won[34] |

| 1990 | Assembly of Experts | — | Disqualified[35] | ||

| 1992 | Parliament | — | Disqualified[36] | ||

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "1982 Assembly of Experts Election", The Iran Social Science Data Portal, Princeton University, retrieved 10 August 2015

- ^ "Sadeq Khalkhali". The Economist.

- ^ Sadegh Khalkhali The Guardian website

- ^ a b c d e f g Ayatollah Sadegh Khalkhali The Daily Telegraph 28 November 2003

- ^ Erdbrink, Thomas (3 May 2018). "A Mummy Turned Up in Iran. Could It Be the Former Shah?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- ^ "Iranian 'Hanging Judge' Dies at 77". AP NEWS. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- ^ "Sadeq Khalkhali (Iranian judge) - Encyclopædia Britannica". Britannica.com. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ Ayatollah Sadeq Khalkhali. Obituary in The Guardian, 1 December 2003 [1]

- ^ Taheri, Amir, Spirit of Allah : Khomeini and the Islamic Revolution , Adler and Adler c1985, p. 113

- ^ Taheri, Spirit of Allah, (1985), p. 187

- ^ Molavi, Afshin, The Soul of Iran, Norton and Co., (2005), p. 9

- ^ Jubin M. Goodarzi (4 June 2006). Syria and Iran: Diplomatic Alliance and Power Politics in the Middle East. I.B.Tauris. p. 296. ISBN 978-1-84511-127-4. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ^ Hoveyda’s Tragic Fate

- ^ Tortured Confessions: Prisons and Public Recantations in Modern Iran by Ervand Abrahamian, (University of California Press, 1999), p. 127

- ^ Molavi, Afshan, The Soul of Iran, Norton, (2005), p. 14

- ^ Sciolino, Elaine, Persian Mirrors, Touchstone, (2000), p. 168

- ^ Martin, Douglas (1984). The Persecution of the Bahá'ís of Iran, 1844-1984. Bahá'í Studies no.12/13. Ottawa, ON: Association for Bahá'í Studies. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-0-920904-13-8.

- ^ Kazemzadeh, Firuz (Summer 2000). "The Baha'is in Iran: Twenty Years of Repression". Social Research. 67 (2): 542. JSTOR 40971483.

- ^ Vahman, Fereydun (2019). 175 Years of Persecution: A History of the Babis & Baha'is of Iran. London: Oneworld. pp. 170–171. ISBN 978-1-78607-586-4.

- ^ Bakhash, Shaul, The Reign of the Ayatollahs: Iran and the Islamic Revolution, New York, Basic Books, (1984), p. 111

- ^ a b Bakhash, Reign of the Ayatollahs, (1984), p. 111

- ^ Qaddafi Meets an Ayatollah The New York Times, 2 January 1992

- ^ Brumberg, Daniel, Reinventing Khomeini : The Struggle for Reform in Iran, University of Chicago Press, 2001, p. 175

- ^ a b Fathi, Nazila (29 November 2003). "Sadegh Khalkhali, 77, a Judge in Iran Who Executed Hundreds". The New York Times Company. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ Obituary from The Economist

- ^ Obituary The Daily Telegraph

- ^ Obituary The Guardian (gives his full name as Mohammed Sadeq Givi Khalkhali)

- ^ صبا, صادق (29 November 2003). "BBC Persian" اصلاح طلبان و در گذشت خلخالی (in Persian). BBCPersian. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ Afshari, Reza (4 November 2010). "Human Rights, Relevance of Culture and Irrelevance of Cultural Relativism". Rooz online. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ Goldstein, Dana (17 June 2009). "IRAN AND THE VEIL". The American Prospect. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ^ Ervand Abrahamian (1989), "To The Masses", Radical Islam: the Iranian Mojahedin, Society and culture in the modern Middle East, vol. 3, I.B.Tauris, p. 195, Table 6, ISBN 9781850430773

- ^ "Getting to Know the Representatives in the Majles" (PDF), Iranian Parliament, The Iran Social Science Data Portal, p. 79

- ^ "Getting to Know the Representatives in the Majles" (PDF), Iranian Parliament, The Iran Social Science Data Portal, p. 206

- ^ "Getting to Know the Representatives in the Majles" (PDF), Iranian Parliament, The Iran Social Science Data Portal, p. 317

- ^ "پنج دوره خبرگان؛ رد صلاحیتها" (in Persian). BBC Persian. 29 February 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- ^ Farzin Sarabi (subscription required) (1994). "The Post-Khomeini Era in Iran: The Elections of the Fourth Islamic Majlis". Middle East Journal. 48 (1). Middle East Institute: 96–97. JSTOR 4328663.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

Further reading

editV. S. Naipaul interviews Khalkhali in two of his better-known books

- Among the Believers: An Islamic Journey (1981) ISBN 978-0-394-71195-9

- Beyond Belief: Islamic Excursions among the Converted Peoples (1998) [part II, chapter 7] ISBN 978-0-316-64361-0

External links

edit- Qaddafi Meets an Ayatollah 2 January 1992