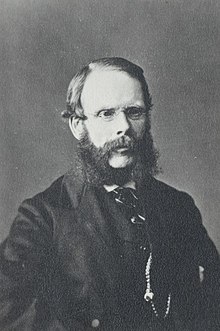

Benjamin Herschel Babbage (6 August 1815 – 22 October 1878) was an English engineer, scientist, explorer and politician, best known for his work in the colony of South Australia. He invariably signed his name "B. Herschel Babbage" and was frequently referred to as "Herschel Babbage". He was the son of English mathematician and inventor, Charles Babbage.

B. Herschel Babbage | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the South Australian Parliament for Encounter Bay | |

| In office 9 March 1857 – 17 December 1857 Serving with Arthur Lindsay | |

| Preceded by | New district |

| Succeeded by | Henry Strangways |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 6 August 1815 London, United Kingdom |

| Died | 22 October 1878 (aged 63) St. Mary's, South Australia |

| Spouse |

Laura Jones (m. 1839–1878) |

| Children | 7 |

| Parent(s) | Charles Babbage (father) Georgiana Whitmore (mother) |

| Relatives | William Wolryche-Whitmore (uncle) |

Early life and family

editBabbage was born in London, the eldest son of Charles Babbage, the renowned Cambridge mathematician who originated the concept of a programmable computer, and Georgina Whitmore. His uncle on his mother's side was William Wolryche-Whitmore, an MP in the House of Commons who lobbied for the formation of South Australia and introduced the South Australia Foundation Act into the British Parliament.[1]

At the age of 18, Babbage became a pupil of the engineer and architect William Chadwell Mylne, with whom he worked on waterworks projects. In the 1840s, he also worked with Isambard Kingdom Brunel, the son of his father's friend Marc Isambard Brunel, on railway planning and building in Italy and England.[1]

Babbage married Laura Jones at Bristol on 10 September 1839. The couple had seven children.[1]

In 1850, Babbage was invited by Patrick Brontë (clergyman and father of the Brontë sisters) to conduct an inspection in the West Yorkshire town of Haworth, partly brought about by Haworth's high rate of early mortality.[2] Babbage was horrified by the unsanitary conditions in the town, and The Babbage Report to the General Board of Health into the town's water supply and lack of a sewerage system resulted in the board taking notice and working to improve the town's sanitation.[3] He performed a similar inspection in the same year in the Herefordshire town of Bromyard, with similar findings.[4] He said that he had "met with considerable opposition to the application of the Public Health Act to this town, from a large number of the inhabitants, upon the ground of the supposed expense of carrying out the sanitary reforms which I found to be so much needed." No action was taken by the town vestry for over twenty years.[5]

South Australia

editIn 1851, the Colonial Secretary Earl Grey, on the recommendation of the geologist Sir Henry De la Beche, assigned Babbage to perform a geological and mineralogical survey of the colony of South Australia requested by the colony's government. Babbage arrived in South Australia on 27 November on the Hydaspes,[6] and over the next few years worked on a number of government projects, first setting up the Government Gold Assay Office in Victoria Square.[7]

He was appointed Justice of the Peace in 1852.[8] In January 1853 he was appointed Chief Engineer by the company undertaking the railway from Port Adelaide to the city.[9] In 1853, Babbage was one of the first five members of the Mitcham District Council, serving as the council's first chairman.[10] A ward in the City of Mitcham was named after him.[11] In 1854 he was elected to the Central Road Board.[12] In 1855, Babbage served as President of the Adelaide Philosophical Society.[13]

In 1857, Babbage was elected to the South Australian House of Assembly in the inaugural election in 1857, representing the electorate of Encounter Bay.[14] He resigned late in the year after being appointed to lead an expedition to explore the north of the colony between Lake Torrens and Lake Gairdner.[15] He was replaced by Henry Strangways in a by-election.[1]

Babbage began his exploration of South Australia in 1856 when sent to search for gold up to the Flinders Ranges,[16] when he discovered the MacDonnell River, Blanchewater and Mount Hopeful (renamed Mount Babbage after him in 1857 by George Goyder). Going beyond the frontier reached in 1851 by explorers John Oakden and Henry Hulkes, Babbage also disproved the notion that Lake Torrens was a single horseshoe-shaped lake or inland sea, ascertaining a number of gaps in the lake, which were later traversed other explorers such as Augustus Gregory and Peter Warburton.[15] On 15 June 1858 near Pernatty Creek he discovered the remains of William Coulthard of Angas Park, Nuriootpa, who had died of thirst around 10 March 1858.[17] On 22 October 1858 he discovered Emerald Springs.[18]

Babbage also discovered that Lake Eyre (sighted by Edward John Eyre in 1840) actually consisted of a large northern and a smaller southern lake. A peninsula on Lake Eyre North was named Babbage Peninsula in 1963.[19]

As Babbage continued his explorations, sometimes accompanied by his son, Charles Whitmore Babbage,[20] the government grew tired of his slow, methodical pace, and the Commissioner of Crown Lands, Francis Dutton, responded to the controversy by replacing him with Peter Warburton in 1858. Babbage complained of unfair treatment and petitioned the House of Assembly to conduct a parliamentary inquiry into the issue.[21] A critically acclaimed book of his pen-and-ink sketches from this expedition is held by the Mortlock Library.[20]

He announced his candidature for the 1877 Legislative Council elections but refused to participate in any public meetings and did not go to the polls.[22] and failed to win a seat.

His last years were spent building a mansion near South Road, St Mary's, where he had an excellent vineyard and was a keen winemaker (nine varieties on 25 acres in 1878[23]). He called the mansion The Rosary, but locals referred to it as Babbage's Castle. It was built in 1873 near the burned-out cottage of John Wickham Daw, on Daws Road, and was massively constructed of concrete in a fantastic baroque style. The building developed structural defects however and remained deserted from around 1905[24] to around 1935, when it was demolished.[25][26]

He died at his home, and his remains were interred in the family vault in the cemetery of St Mary's on the Sturt.[27]

Family

editBabbage married Laura Jones (c. 1813 – 22 July 1899) at Bristol on 10 September 1839. Among their children were

Charles Whitmore Babbage (1842 – 17 August 1923), their eldest son, was a prize-winning student at Adelaide Educational Institution 1853–58.[28] Herschel wrote to his father

- "I have found a good school for the boys, John Lorenzo's non-denominational school. The largest private independent school in South Australia at this time."[29]

Charles accompanied his father on his journeys of exploration 1857–62, recording scenes in a small sketchbook which has been preserved.[30] He was a member of the Adelaide Philosophical Society and for some years its Honorary Secretary. He married Amelia Barton on 28 July 1869. While working as a teller with the Bank of Adelaide he started speculating on the Stock Exchange and losing money. On 1 July 1876 he was charged with embezzling £1616, and in September was sentenced to seven years imprisonment for that and passing a fraudulent cheque.[31] During his internment his wife ran their home as a boarding house for students of Prince Alfred College[32] and ran drawing classes.[33] His family moved to New Zealand in 1881.[34] He was released from prison some time after 1880 and moved to New Zealand, for a while farming in Wanganui, then "Croftmoor" near Hāwera from 1883[35] to 1894 then moved to St John's Hill, Wanganui where he took an active role in local affairs, and was a prominent member of the Camera Club and the Wanganui Astronomical Society.[36] He was active in the Beautifying Society and did much work on Virginia Lake. His wife was on the board of the Wanganui Orphanage from 1896 to 1918 and president from 1910. Their home "Rotokawau" was on St John's Hill above the Winter Garden; the gully at the rear is called "Babbage's Gully".[37] He died at home after a brief illness.[38]

The National Library of New Zealand has a collection of his photographs.[39] Babbage Place in Wanganui was named for him.[40]

- Charles Ernest Babbage (17 June 1870 – 24 December 1878)

- Alfred Whitmore Babbage (26 Oct 1871 – 27 June 1957) married Kate Elizabeth Hobbs on 7 July 1900

- Henry Herschel Babbage (6 October 1873 – c. 1947)[41]

- Herbert Ivan Babbage (10 August 1875 – 14 October 1916) was a noted N.Z. artist who studied under David Edward Hutton (1866–1946) then at Académie Julian, Paris. He died in England while serving with the Royal Defence Corps in World War I.[42] The National Library of New Zealand has a collection of his photographs.[43] Wanganui's Sarjeant Gallery has six of his paintings.

- Gordon Swaine Babbage (c. 1885 – c. 1 July 1975) in Wanganui, married Florence Mabel Josephine Rutherford (c. 1893 – c. 1 September 1940) on 14 April 1914

- Dr. Stuart Barton Babbage (4 January 1916 – 16 Nov 2012), born in Auckland, married Elizabeth King in 1943,[44] became Anglican Dean of Sydney in 1947, then of Melbourne (and Principal of Ridley College) in 1953.[45]

Eden Herschel Babbage (c. 1844 – 5 February 1924) was also a prize-winning student at AEI 1853–1859.[28] He married Louisa Harriot Burton (d. 22 September 1917) on 30 April 1872. An employee of the Bank of Australasia from 1860, he was transferred to Sale, Victoria in 1877 then promoted to manager of the branch at Wanganui, New Zealand,[46] followed by successively more responsible posts until his retirement in 1906 at his home "Rawhiti" on Clanville Road, Roseville, New South Wales, where he was active as councillor and president of the Progress Association. A memorial was erected to him, the "Father of Roseville" on the corner of Babbage Road (which was named for him)[47] and Ormonde Road,[48]

- Francis Eden Babbage (8 May 1873 – 1 April 1949) married Eleanor Mary Molesworth on 11 February 1903. He followed his father in the Australasian Bank.[49]

- Max Babbage (13 January 1908 – )

- Neville Babbage (5 February 1912 – ) collected much Babbage ephemera now held by Sydney's Powerhouse Museum.

- Zara Georgina (20 February 1875 – ) born in Adelaide

- Laura Louise Irene Babbage (19 January 1881 – ) born at Wanganui N.Z.

Henry Stainton Babbage (29 September 1853 – 11 June 1889), his youngest son, was also a prize-winning student at AEI. He married Emma Rosetta Leverington. His twin, Ada Isabella Babbage died in 1855.

- (Rupert Clement) Henry Stainton Babbage (1889 – 21 January 1943) married Dorothy Alexanderina Brown in March 1912. They divorced in August 1938. He married again, to Myrtle, née Ramsdon.

Ada Rosalie Babbage (12 November 1855 – 1936) married William D. Clare on 16 Nov 1881

Dugald Bromhead Babbage

editHerschel's brother Dugald Bromhead[50] (13 March 1823 – September 1901) arrived in Adelaide on the Grecian on 24 September 1849[51] and worked a farm on Goodwood Road. He worked as assistant to his brother in the Assay Office in 1852, helped found the Adelaide Philosophical Society in 1853 and in 1854 surveyed the route of the proposed Port Adelaide to Adelaide railway.[52] Herschel, while protective of his less able younger brother, despaired of his propensity to mix with social inferiors and his fondness for drink.[53] He married Anne Lea at Sturt on 7 March 1854. Their children included:

- Dugald Herschel Babbage (15 December 1854 – ) returned to UK on the Orient in 1882[54]

- Walter Henry Babbage (1 August 1856 – 18 December 1883)

- Louisa Ann Babbage (18 January 1859 – ?)

Sources

editTee, Garry. "Charles Babbage's Contributions to Statistics" (PDF).

References

edit- ^ a b c d Symes, G. W. (1969). "Babbage, Benjamin Herschel (1815–1878)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 3. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- ^ "The good old days were horrible". Gadling. 12 October 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- ^ Dinsdale, Ann; Warner, Simon (2006). The Brontës at Haworth. London: Frances Lincoln Publishers. ISBN 0-7112-2572-9.

- ^ "House drainage and disease". South Australian Register. 10 May 1855. p. 3. Retrieved 10 September 2024 – via Trove.

- ^ Bromyard – a Local History, ed. Joseph G. Hillaby and Edna D. Pearson, Bromyard and District Local History Society, 1970

- ^ "Shipping Intelligence". South Australian Register. 28 November 1851. p. 2. Retrieved 29 September 2011 – via Trove.

Mr and Mrs Babbage, four children and two servants - ^ "The Assay Office". South Australian Register. 22 April 1852. p. 2. Retrieved 29 September 2011 – via Trove.

- ^ "Appointments". South Australian Register. 10 September 1852. p. 2. Retrieved 29 September 2011 – via Trove.

- ^ "Latest from America". South Australian Register. 15 January 1853. p. 3. Retrieved 29 September 2011 – via Trove.

- ^ "Advertising". The Adelaide Times. 10 October 1853. p. 4. Retrieved 27 June 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ "Babbage Ward" (PDF). City of Mitcham. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 February 2011. Retrieved 26 October 2010.

- ^ "The Central Bard". South Australian Register. 24 January 1854. p. 3. Retrieved 29 September 2011 – via Trove.

- ^ "Royal Society of South Australia Presidents". Archived from the original on 4 April 2012.

- ^ "Benjamin Babbage". Former members of the Parliament of South Australia. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ a b "Taking it to the edge: Land: To the north – Babbage, Warburton and Gregory". 7 February 2007. Archived from the original on 11 March 2011.

- ^ "The Gold Search Expedition". South Australian Register. 3 January 1857. p. 2. Retrieved 26 February 2012 – via Trove.

- ^ "Family Notices". South Australian Register. 10 August 1858. p. 4. Retrieved 29 September 2011 – via Trove.

- ^ "Coward Springs Oodnadatta Track South Australia". Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ^ "Place Names of South Australia: Babbage, Mount". State Library of South Australia. Archived from the original on 5 April 2015.

- ^ a b "Benjamin Herschel Babbage". Dictionary of Australian Artists Online. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- ^ "Petition of Mr. Babbage". The South Australian Advertiser. p. 2. Retrieved 27 October 2010.

- ^ "Death of Mr. B. H. Babbage". South Australian Register. 2 November 1878. p. 7 Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- ^ "The Vintage of 1878". South Australian Register. 10 July 1878. p. 6. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ^ "Sun and Shade on Crumbling Stone". The Register News-Pictorial. Adelaide. 24 May 1930. p. 12. Retrieved 20 July 2013 – via Trove.

- ^ "Strange Tales! of Some Ruins". The Advertiser. Adelaide. 29 June 1935. p. 9. Retrieved 20 July 2013 – via Trove.

- ^ "Babbages Castle".

- ^ "Our City Letter". Kapunda Herald. Vol. XIV, no. 1079. South Australia. 25 October 1878. p. 3. Retrieved 2 April 2019 – via Trove.

- ^ a b There is no reason to believe that Thomas William Babbage (4 October 1859 – 1945), a fellow student and later manager of the Glenelg Railway Company, was closely related.

- ^ Chessell, Diana Adelaide's Dissenting Headmaster: John Lorenzo Young and his Premier Private School Wakefield Press 2014 ISBN 978 1 74305 240 2

- ^ Reeder, Stephanie Owen The Vision Splendid National Library of Australia 2011 ISBN 978-0-642-27724-4

- ^ "The Chief Justice". South Australian Advertiser. p. 5. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ^ "Prince Alfred College". South Australian Register. 3 October 1876. p. 7. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ^ "Education". South Australian Register. 16 February 1877. p. 1. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ^ "Shipping telegrams". The Star. 14 March 1881. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- ^ "News and notes". Hawera and Normanby Star. 19 January 1884. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- ^ "Concerning People". The Register. 13 April 1916. p. 4. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ^ Kirk, Athol L. Streets of Wanganui first published 1978, 2nd ed. 1989 ISBN 0-473-00746-0

- ^ "Obituary". Hawera and Normanby Star. 20 August 1923. p. 4. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- ^ [1][permanent dead link].

- ^ Tee, Garry J. "The Rutherford Journal".

- ^ "Advertising". Sydney Morning Herald. 6 January 1948.

- ^ "Ferner Galleries | Herbert Ivan Babbage". Archived from the original on 25 May 2010. Retrieved 2011-09-30.

- ^ photographs[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Brigadier weds". The Evening Post. 14 June 1943. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- ^ Blackler, Stuart (March 2005). "Book review Memoirs of a Loose Canon". Tasmanian Anglican. Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- ^ "Mr E. H. Babbage". South Australian Register. 30 November 1886. p. 5. Retrieved 1 October 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Stroud House – photograph by E.H.B." Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- ^ "Babbage Memorial". Sydney Morning Herald. 7 August 1924. p. 8. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- ^ "Parkes, Saturday". Sydney Morning Herald. 16 December 1907. p. 5. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- ^ Though frequently spelled "Bromheald", this is almost certainly an error. Sir Edward Ffrench Bromhead was a friend and admirer of Charles Babbage.

- ^ "Shipping Intelligence". South Australian Register. 26 September 1849. p. 3. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ^ Cumming, D. A. and Moxham, G. They Built South Australia published by the authors 1986 ISBN 0-9589111-0-X

- ^ Wilkes, M. V. (2002). "Charles Babbage and His World" (PDF). Notes and Records. 56 (3). London: 353–365. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2002.0188. S2CID 144654303. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- ^ "Shipping Intelligence". South Australian Register. 9 January 1882. p. 4. Retrieved 1 October 2011.